The Bizarre History Of Ellis Island

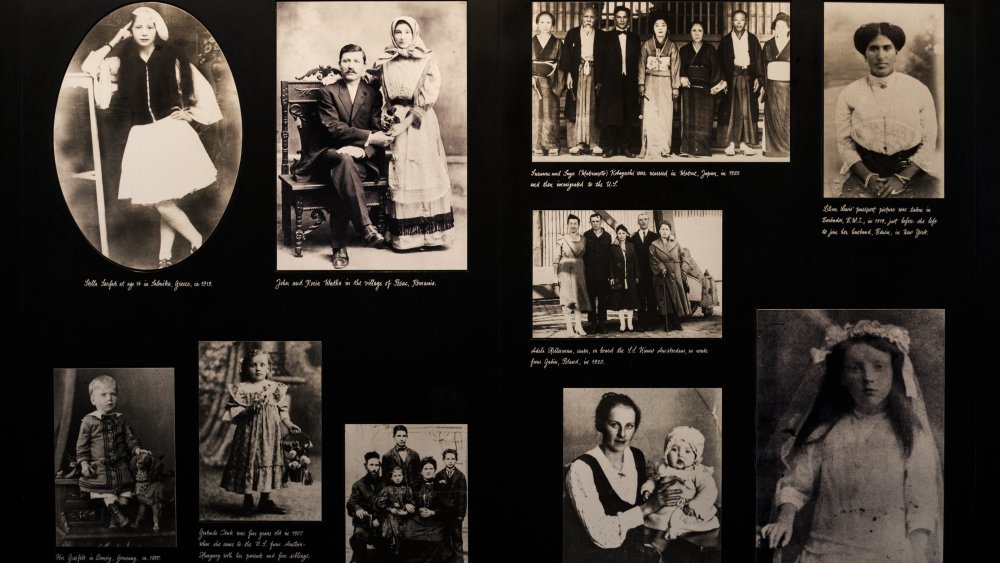

There are a handful of locations around the US that hold a special place in history, and Ellis Island is one of those: according to The New York Times, it's estimated that 40 percent of 21st-century Americans can trace their family back to their US origins and find someone who passed through the immigration center on Ellis Island.

The numbers are shocking: between 1892 and 1954, more than 12 million people crossed the island on their way to starting a new life. (If your family came to the US just a little bit earlier, between 1855 and 1890, chances are pretty good they were one of the estimated 8 million people who passed through Ellis Island's little-known predecessor, Castle Garden. Can't find proof? That's not surprising: a massive fire in 1897 destroyed more than 40 years of records.)

It's difficult to imagine what walking through Ellis Island must have been like — a chaotic hustle and bustle of people feeling equal parts fear and hope, the chatter in all different languages, the squeal of excited kids. But it didn't always look like that: Ellis Island has actually changed a lot over the course of its history, and only a small part of that was spent as the gateway to the US.

Things were very different before the Europeans came

Ellis Island's immigration center opened in 1892, but the National Park Service says both Ellis Island and the neighboring Liberty Island were an important part of the day-to-day lives of the nearby Algonquian tribes starting in at least 994 AD.

Just a quick glance at New York's and New Jersey's waterways now and it's clear things are in a dire state in the 21st century — according to Riverkeeper, they're filled with cigarette butts, foam, and more plastics than a person can realistically imagine being in one place. That makes it hard to picture today, but for centuries, the waters around the two islands were filled with wildlife. Oysters, crabs, clams, fish ... there were plenty of small animals, too, and the islands were such an important food source for so long that when the Dutch discovered the harbor, they named Ellis and Liberty islands the "Oyster Islands."

At first, the European settlers and the Native Americans shared the land and traded — often, it was a trade of furs and pelts (and the right to hunt) for things like tools, weapons, and cast iron. But after only a few decades of contact, conflict and disease pushed the tribes out of the area, and in 1674, "Little Oyster Island" was given to one Captain William Dyre.

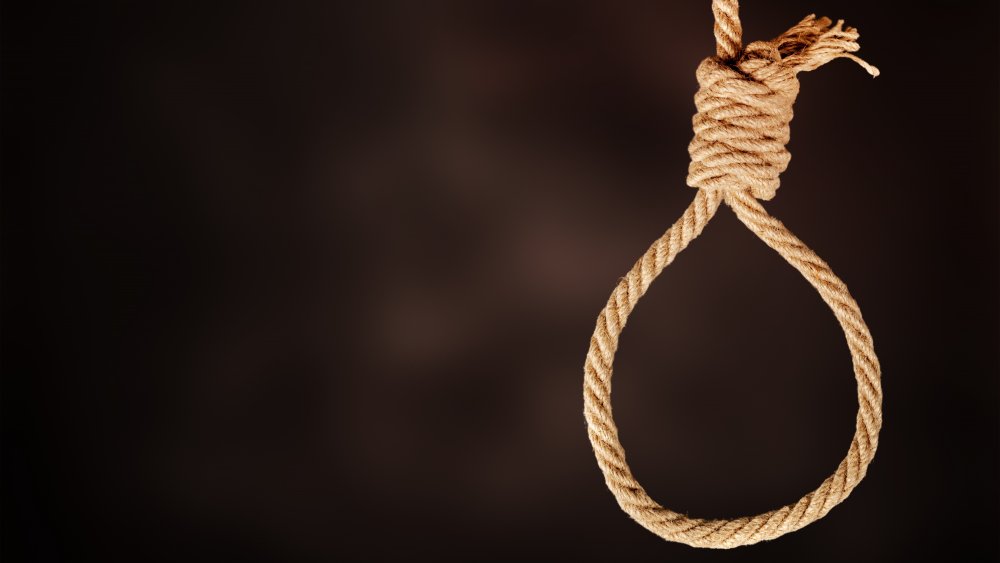

For years it was a place of executions

Ellis Island has changed hands a lot over the course of its history, and according to the History of New York City, one of the most... colorful names it had was undoubtedly Gibbet Island. It picked up that grisly moniker at some point in the 18th century, and the reason for it is exactly what it sounds like. Numerous executions took place on the island, and most were people found guilty of piracy. Then, there was also the sordid little addendum that the bodies were left hanging as a warning for others.

Many of the names have — perhaps unsurprisingly — been lost to history, but there's a few remembered by the books. According to the National Park Service, Charles Gibbs and Thomas J. Wansley met their end with a hangman's noose on April 22, 1831. Their crime? Mutiny, sparked by the desire to seize a ship full of silver. The captain and the first mate were killed, so then the pirates were, too.

It's also worth a footnote that Liberty Island was used for hanging pirates, too; in 1860, The New York Times reported on the long list of hangings that happened on the island then called Bedloe's. Among them were Cornelius Wilhelms — for attempting to seize a ship and killing several female passengers in the process — and Elias Hicks, for "similar crimes."

Ellis Island is actually sort of in New Jersey

According to The New York Times, there's been a lot of debate over whether Ellis Island belongs to New York or New Jersey. It is, after all, just 1,300 feet from Jersey and more than a mile from New York City, specifically Manhattan, but distance doesn't always matter.

The whole thing started back in 1664, with a grant that described New Jersey as "bound on the east part by the main sea, and part by Hudson's river." According to New Jersey, that meant they were entitled to everything up to the halfway point in the river, while New York said that no, their claim ended on the river's shore. It seems like a minor debate, but it left Ellis and Liberty Island up for grabs. That continued until 1834, when the states decided on boundaries and New York got the islands. But it got more complicated. The waters around the islands were technically New Jersey's, but when New York started digging subways and dumping fill into the waters to enlarge the islands, well, who owns that bit now? The federal government! Isn't red tape fun?

Then, in 1986, a National Park Service employee lost part of his leg, and no one could decide who was responsible. In the end, New York kept Liberty Island and New Jersey kept Ellis Island ... except for 4.68 acres, which still belong to New York.

Getting in and out of Ellis Island could be very easy...

Anyone who's stood in line for an international flight knows what a hassle it is. Surely, immigrants coming to Ellis Island for the first time had it harder... right?

Fun fact: according to The Statue of Liberty — Ellis Island Foundation, first and second class passengers didn't have to go through the queues on the island at all. Their questions were answered on board the ship, and as they had already proved themselves wealthy enough to afford the expensive tickets, they were shown into the country. The thinking was that these passengers were unlikely to become a burden to society, but for those traveling in steerage, that wasn't as clear-cut.

Those were the passengers that waited in long lines, answered various questions, and underwent a medical exam. Ellis Island employees would be working off something that was basically a cargo manifest for passengers, and before the ship was even allowed to dock, it was quarantined so doctors could look for signs of highly contagious diseases like smallpox. Passengers were given tags that corresponded with the manifest and surprisingly, History says that for about 80 percent of people, they were through Ellis Island and into the US in just a matter of a few hours.

... or, getting out of Ellis Island could be very hard

If, as History says, 80 percent of immigrants had an easy time getting through Ellis Island, what about the other 20 percent? It varied. According to PBS, most of the people who were detained or denied entry were those thought to run the risk of becoming a burden on society. That makes sense, but the list of these people looks pretty strange. Stowaways and criminals weren't allowed through, but neither were Bolsheviks, and anyone deemed to be "immoral." There's a lot of grey there, and at the top of that list were children and unescorted women — especially if they were pregnant.

Some were were turned away for medical reasons or held in Ellis Island's hospital, but this was the case for less than 1 percent of immigrants. Still, that's around 80,000 people, and the AMA Journal of Ethics says there was a variety of reasons people could be stopped. But some were given medical care, and by 1907, it had been established that treating those who needed to be hospitalized was simply the right thing to do.

Other times, people were turned away because it was decided they had an inability to work and support themselves. The reasons for this included old age, hernias, poor vision, deformities of the arms, legs, or spine, and even varicose veins. Still, the growing country needed laborers, and most were pushed through.

Pass or fail: the feature profile test

Ellis Island officers were particularly concerned with the mental acuity of immigrants, and according to the AMA Journal of Ethics, anyone who didn't quite measure up in the eyes of officers was pulled aside for a mental examination. They were often gives puzzles to complete or a group of cubes, and asked to perform certain tasks. This was harder than it sounds — remember, these people have just spent a long time in a very uncomfortable, crowded ship in conditions that were unsanitary at best. Many were exhausted, hungry, and scared, and a lot of them didn't speak English.

The Smithsonian has one of the puzzles they were given, and honestly? Even English-speakers who know the wooden blocks fit together somehow might be hard-pressed to figure out what it's supposed to be. It's called the Feature Profile Test, and in theory, it's supposed to confirm a person knows where facial features belong on a face. It was developed by Howard A. Knox, and it was actually a major advancement. Before, people were tested with more traditional IQ tests — and given the language barrier and culture shock most were working with, it really wasn't effective. Still, that simple wood puzzle almost perfectly illustrates why Ellis Island received its immigration-era nickname: the Island of Tears.

The first immigrants through Ellis Island were children traveling alone

While you might expect Ellis Island's immigrants to be made up of young adults heading out for adventure or families packing up and moving all at the same time, there were actually millions of unaccompanied minors who made the trip on their own.

The very first person in line to go through Ellis Island on its opening day was 15-year-old Annie Moore, and she made the trip from Ireland with her two little brothers in tow, and no adults. Her parents had made the undoubtedly difficult decision to go on ahead; they had made the trip three years prior, and were waiting to greet the children when they got off the island.

That wasn't the case with everyone, though. By 1907, unaccompanied minors had become such a common occurrence that legislation was put in place to deal with them. It's not as dire as it sounds, though, and Mother Jones says there was a whole network set up to help the children — who were often orphans. After being detained on the island, a hearing would be held to decide what to do with them. But there's good news: churches, synagogues, missionaries, well-to-do private citizens, and immigrant aid societies were often on hand at the hearings, and would offer to be the child's guardian. In the meantime, children would be under the stewardship of matrons on the island.

No names were changed on Ellis Island

It's a common story — if your own family doesn't tell it, there's a good chance you know someone who does. Names, popular belief goes, were "Americanized" at Ellis Island. They were misheard, misunderstood, or just made easier for the people already living in the US to understand. Only it didn't happen. At all.

Like... never, ever. According to the New York Public Library, there's a very simple reason we know this: inspectors at Ellis Island never wrote down or copied names. They only compared names to those listed on ships' manifests, and the only thing they were looking for was to make sure everything matched. So, what happened? Most of the immigrants that did have their names changed did it themselves. Some did it to sound more American, and some figured that since they were starting a new life, they might as well start completely fresh.

There was one exception, and it's pretty awesome. A passenger named Frank Woodhull was pulled aside for suspected tuberculosis, and found to be a person actually named Mary Johnson. After spending 15 years living as a man in order to broaden the array of opportunities before him, Woodhull/Johnson found himself in front of an Ellis Island hearing. The verdict? He was "a desirable immigrant [who] should be allowed to win her livelihood as she saw fit." And his name was officially changed.

Families didn't always know what happened on Ellis Island

Families weren't judged as families, they were judged on an individual basis. And that, says the AMA Journal of Ethics, means they were often separated. Husbands and wives, parents and children ... and sometimes, they didn't know what really happened to the members of their family.

Take the story of Fritz and Martha Strahm. They were a Swiss couple who arrived at Ellis Island in December 1920. They had their two children, they'd been traveling for a month at that point, and when they landed, their 2-year-old son, Walter, was sick. He was diagnosed as having the measles, pneumonia, and scarlet fever, and was immediately hospitalized. He was essentially quarantined there, with one parent able to visit him for just five minutes each week of the six they were there. According to the Los Angeles Times, little Walter died on February 9, 1921. His parents were never told what was going to be done with the body, they were simply sent on their way. The Strahm family says they always wondered what had really happened, and it wasn't until 66 years later that they were finally able to get a death certificate.

CBS says this wasn't unusual. In addition to the 350 babies born on the island, around 3,500 people died there. Most had no money, and were laid to rest in the unmarked graves of paupers.

Eugenics and ableism

According to Europe Now, Ellis Island became a sort of research facility for those who were pushing an agenda of eugenics and scientific racism. They had a champion in Ellis Island's commissioner of immigration, William Williams. Williams had very specific ideas on who should be allowed in, and he talked freely about it to the New York Daily Tribune in 1909. He was all for getting rid of the "undesirable minority;" for example, Italians from the north, he said, were better than the ones from the south, as the northerners tended to be stronger, smarter, better with money, and literate. He saw a lot of immigrants coming from the south, though, and that just wouldn't do.

He also condemned the fact that he couldn't send the Germans, British, French, and the Swedish right back to where they came from, and if it was cheap labor the US wanted, they should look to China. Why? Because they were a people "who can work hard and who can live on less than almost any race in the world."

But in the end, between 4 and 8 percent of immigrants were officially classified as undesirable, and of those, only about 11 percent were deported. That was in large part because it was the ship captain's responsibility for taking a person back to their home country, so they'd often step in and vouch for those having trouble getting through.

'A concentration camp with steam heat and running water'

Ellis Island closed as an immigration center in 1954, and by that time, it was hovering on the brink of what it would ultimately become: a detention center.

Let's take the story of Ellen Knauff (via Time), a German woman who served in the UK's Royal Air Force and in the US Army during WWII. She was married to Kurt Knauff, a US citizen and Army veteran, and when she tried to join her husband in the US after the war, she was stopped at Ellis Island. She was detained in the place she called "a concentration camp with steam heat and running water," and many of the others she found being held there were also German, Japanese, or Italian. No one told her why she couldn't leave and eventually the Supreme Court told her the processes that kept her there were more important than her. Eventually — after two years in captivity — she learned she had been accused of being a Communist spy.

She wasn't alone. According to Atlas Obscura, Ellis Island served as a detainment center for somewhere between 1,600 and 1,800 people deemed threats during World War II, and during the Cold War, thousands of people were held there for months and many spent years of their lives there ... all without knowing why.

Protests and occupation of Ellis Island

Sometimes, things go full circle ... or at least, they try to. For centuries, the island most recently named Ellis Island was a valuable source of food for Native American tribes, and in 1970, their descendants tried to take it back. According to the New York Public Library, they had been inspired by the sit-in protests on Alcatraz, and decided to do the same thing on Ellis Island.

Fourteen tribes were represented by the 38 people who attempted to get to the island and set up an occupation. They didn't make it — a boat malfunction delayed them enough that the National Park Service and the Coast Guard were alerted, and stepped in to stop it. No one was arrested, but it wasn't the end of attempts to claim control of the island.

That same year, the National Economic Growth and Reconstruction Organization asked to use the island: they wanted to take all the buildings that were already there — but already decaying — and set up a new, self-sustaining community and rehab facility. They did ask the White House, but the White House didn't answer — so they moved in. Most left before the National Park Service could give their blessing — and they did — but when the group's leader found himself in the middle of some legal troubles, the whole thing just sort of fell apart. On Sept. 9, 1990, Ellis Island was finally reopened as a museum.