The True Meaning Behind The Guy Fawkes Mask

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

"Remember, remember," theatrically inclined teenagers will tell you, "the fifth of November." And then, almost inevitably, they tend to forget what that whole "gunpowder treason and plot" was all about. Over the last forty years, Guy Fawkes and his grinning visage have occupied an ever-growing corner of the societal hive mind, joining the likes of Santa Claus and the Kellogg's Corn Flakes rooster as folkloric heroes whose origin stories get lost in the mix.

The truth behind the mask is so much more metal, so much more punk, than anybody seems to give it credit for nowadays. It's a down and dirty story about an always en-vogue, youth-fueled, high-octane attempt to reinstate papal supremacy in 17th century England.

So punk.

Fawkes and Friends

It was 1605, and England was on the outs with Catholicism after Henry VIII's royal decree a few decades prior that nobody was allowed to tell him who he could and couldn't marry. English heads of state were required to swear allegiance to the Church of England or face that most gruesome of penalties: a fine. Also, you know — torture and execution.

Needless to say, Catholics weren't tickled, and when King James I got down to ruling without much more than a half-hearted "Catholics are people, too," a small group of dissenters decided it was time to blow something up, namely the House of Lords.

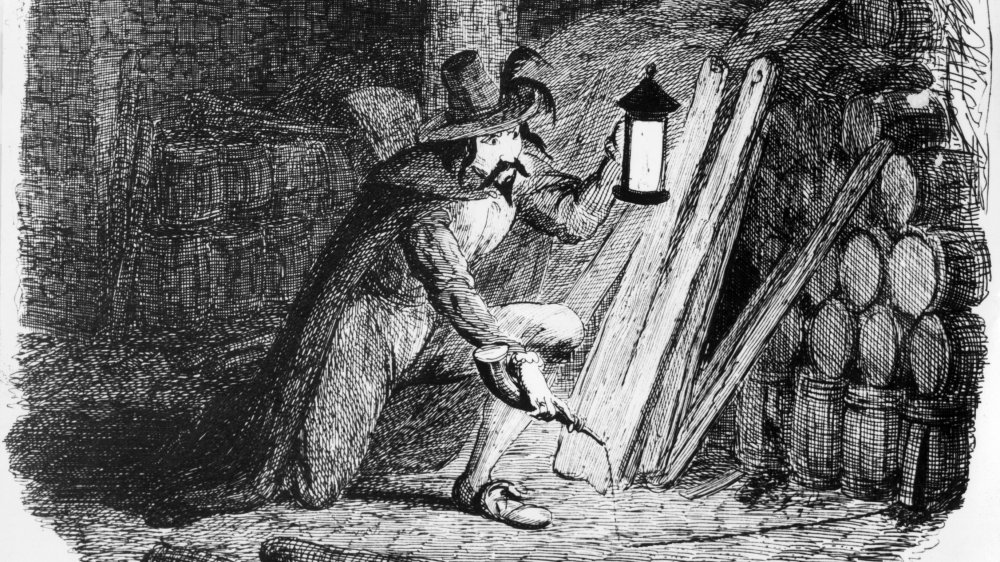

Things didn't go great. One of the plotters sent a letter to a member of parliament who he presumably didn't want to see exploded, and some severe snitching went down. As a result, Guy Fawkes, the point-man on the operation, found himself very much arrested, looking up at the buildings he'd failed to level and asking himself that most Marvin the Martian of questions, "where's the kaboom?"

The wrong guy for the job

Around 370 years went by. Burning Guy Fawkes in effigy every year came in and out of style in England. Somehow, nobody ever came up with the idea of fighting him in effigy, even though the name "Fawkesy Boxing" was hanging right in front of their faces. A comic book writer named Alan Moore, riding the creative fence between the brilliance of his Swamp Thing stories and the bananas-level lunacy of his later work, released a graphic novel titled V for Vendetta, published piece by piece in the pages of Warrior. It was the story of a man (nay! An idea!) called V, pushed to acts of terrorism by a utilitarian government. 24 years later, the Wachowskis collaborated with director James McTeigue to create a film adaptation.

The movie found a devoted audience in frustrated citizens of a post-9/11, mid-Patriot Act world, and its use of Guy Fawkes iconography struck a chord. The closing scene was especially revered, as hundreds of perturbed citizens donned Fawkes masks of their own and took to the streets under the banner of a man who, in the comic book, dies telling people that they don't need a leader.

The Fawkes and AT&T merger

Ironic? Yeah. Doubly ironic since the real Guy Fawkes definitely did want people to have a leader, specifically the pope? Double yeah. Triple ironic since, according to History, Fawkes avoided the martyrdom associated with his name by jumping off the scaffold before he could be hanged? Maybe. We've gone full Alanis and lost track of what is and isn't ironic at this point. But the imagery was ingrained, and protesters around the world adopted the V visage as stylish shorthand for "down with the man." Today, the mask is synonymous with the Occupy Movement, Anonymous, and dissent.

Fun side note, did you know that AT&T, through their acquisition of Time-Warner, owns the merchandising rights on all licensed V for Vendetta properties? It's true! Every time a ubiquitous anti-corporate mask is sold, a cut goes to Fortune 500's ninth largest corporation in America, even the ones used in the net neutrality protests against AT&T. So punk. So, so punk.