Weird Things People Believed 200 Years Ago That Ended Up Being Totally Wrong

Two hundred years ago, the world would have looked simultaneously familiar and dramatically different. Certainly, there were humans around speaking more or less modern languages and conducting themselves in the sort of curious, messy way that modern folks do, too. But people of this era were also prone to believe in some things that would seem especially odd to us today. Do you wash your hands after using the bathroom, for instance? (Please tell us you do.) Well, that may well have been odd in some quarters, even if someone were a doctor in a hospital full of sick patients.

While we're at it, those doctors might have been carting about kits full of medical equipment and treatments that might have you taking a step back, whether it was at the sight of leeches squirming about or a pill bottle full of mercury. Oh, and don't even ask about graham crackers, unless you want to be really disappointed. Though the people of the early 19th century weren't totally off the wall on some things, this will prove that they were utterly wrong about quite a few others.

Ew, you wash your hands?

Nowadays, the idea of scrubbing up is utterly basic to the medical field. But, travel back to the 1820s and ask a doctor to break out the soap, and you might get the stink-eye — or worse. In the early 19th century, handwashing was largely seen as a cultural or religious practice. Early writers and scientists, like the 12th-century Moses ben Maimon (or Maimonides), did make a connection between washing one's hands and better health outcomes, but they were the odd ones out in a decidedly grungy landscape.

As the 19th century got going, hospitals were often regarded as places where one could get sick and die in short order. Doctors were known to routinely go from procedure to procedure without any real attempt at sanitizing or cleaning themselves in between; one might conduct an autopsy and then attend to a living patient giving birth, for instance. It wasn't until the 1840s that one pioneering physician, Ignác (or Ignaz) Semmelweis, took a hard look at mortality numbers in Austria's Vienna General Hospital and realized that handwashing could save lives. When he implemented the practice for physicians under his direction, it dramatically cut down on deadly infections in the hospital's maternity ward. Yet Semmelweis was reluctant to publish his research, given that he experienced dramatic resistance from other doctors who resisted the notion that they were the dirty disease-carriers. Semmelweis didn't help things by being rather abrasive, and he was later committed to a mental institution.

The graham cracker was connected to temperance

If you've ever chowed down on a graham cracker, you already know that the sugary carb is delightful. But its inventor may have been horrified by your hedonism. That would be Sylvester Graham, an American preacher who was also an unconventional health advocate. Graham was an especially intense follower of the growing temperance movement, advocating not just for cutting out alcohol, but just about anything people found enjoyable. This lengthy list of no-nos included meat, caffeine, tobacco, soft mattresses, tight clothes, and spices. Graham argued that avoiding these and other vices would tamp down the immoral urges that, when indulged, supposedly caused health conditions ranging from upset tummies to mental illness.

Some of Graham's advice wasn't totally off-base — he urged people to get regular exercise and drink plenty of water, for instance — but his namesake cracker was still weird. By the time it debuted in 1829, he had already developed a pared-down diet that consisted mostly of fruits and veggies, as well as whole grains. The graham cracker was part of this "Graham Diet" and consisted of a rather grim mix of whole wheat flour without sugar, fat, or salt. Essentially, it was meant to be so boring that people wouldn't be driven to indulgence and sin. Yet, Graham never applied for a patent, meaning others began messing with the recipe. The current version most of us know has its roots in a sweetened, mass-produced cracker produced by Nabisco in 1898.

Phrenology had alarming traction

For a while there, the pseudoscience of phrenology claimed that you could gain insight into a person's intelligence, future, and indeed their very soul, by noting the shape of their head. It's based on a complex melange of ideas that arose in the late 18th century and almost immediately became controversial; Holy Roman Emperor Francis II even temporarily banned lectures on phrenology. But something about the notion took hold, as the first sort of advocacy group for the discipline, the Edinburgh Phrenological Society, was established in 1820. In the U.S., lecturers on the subject were warmly received and phrenology was seen as an intellectual, high-class pursuit. The trend died down and became almost embarrassing in the 1840s, through phrenological concepts persisted into the 20th century.

The strange history of phrenology was based on the idea that different regions of the brain focus on different tasks or concepts. So far, it doesn't sound so bad from a modern perspective, but phrenology goes on to maintain that the more "developed" a faculty is, the bigger its dedicated part of the brain will be. Then the brain will literally get bigger and push out the skull in that spot. A phrenologist might have argued that interpreting this skull shape is more complex than finding a bump or lump in the right region (those regions were pretty much arbitrarily chosen, by the way). Still, it was all too often used to enforce boundaries based on race, gender, class, religion, and mental health.

Spontaneous generation was still seen as a thing

Something can't just come from nothing ... right? Well, no, but the once-popular theory of spontaneous generation had at least some people of the 1820s thinking just that. The idea was that organic life could somehow arise from inorganic matter. How else could fly larvae suddenly appear in rotting material, after all?

While at least a few people were getting skeptical at the dawning of the 19th century, the notion of spontaneous generation was still definitely around by the 1820s. Decades later, in 1859, scientist Felix Pouchet published work still suggesting that maybe at least small creatures like bacteria might still come about through spontaneous generation. The French Academy of Sciences established a contest awarding a hefty 500 francs to anyone who could settle the matter once and for all. Then, Louis Pasteur entered the ring.

Pasteur, who at the time was basically a scientific nobody (but who definitely wasn't above a weirdly intense scientific rivalry), argued that Pouchet's experiments were poorly controlled and allowed free-floating bacteria to enter test containers. He repeated Pouchet's test, but added a twist: While preparing the test solution, he heated a glass flask's neck and drew it out into a long, thin curve that was almost sealed off. No microorganisms grew in Pasteur's flask. Yet, others still held on to parts of the belief, such as the possible notion that dust was part of spontaneous generation. Still, the Academy gave Pasteur the win.

Bloodletting cures all ills ... maybe

If you had a medical problem in the early 19th century, the doctor who attended you might just break out the knives and leeches. It sounds positively medieval to some, but the by-then ancient practice of bloodletting may have seemed so established it hardly warranted a second thought. It has its basis in humoral theory, in which the body operates under four "humors" — black bile, yellow bile, blood, and phlegm. An imbalance in these can cause all manner of illnesses, so it stood to reason that letting some blood out could ease at least a few conditions.

It may have seemed pretty professional when the doctor entered a patient's room and began opening his bloodletting kit (or at least when the local barber-surgeon did), but this practice almost certainly killed some. George Washington, who died in December 1799 after complaining of a sore throat, may have been fatally weakened by physicians who bled him of five or more pints (at Washington's insistence, to be fair).

Though bloodletting finally fell out of favor by the last decades of the 19th century, the 1820s still saw plenty of this practice. One popular way of going about it involved leeches. In fact, this decade saw something of a trend for the little bloodsuckers, with London's St. Thomas' Hospital using an estimated 50,000 leeches in 1822 alone (a dramatic increase from previous years). Instead of just slapping a leech wherever, a tube would be used to direct the animal to a specific part of the body.

The hollow Earth theory was really getting started

If you're a geologist or just took a passing glance at an Earth sciences textbook once, then you surely, hopefully understand that our planet is pretty solid. Generations of research has demonstrated that Earth is very definitely not hollow, instead being full of solid rock and semi-liquid magma. But if you were a scientist or a certain sort of loudmouth 200 years ago, you would perhaps be less certain.

While it may be a fringe belief nowadays — at least one historic cult in Florida excepted — the notion of a hollow Earth hiding unknown wonders seemed almost possible back then. Indeed, it has been around in one form or another since ancient times, with even scientific notables like 17th-century astronomer Edmund Halley suggesting the inside of the Earth was a series of wobbly nested shells that messed with compass readings and perhaps also contained living beings.

The theory got a dubious boost in the 1820s, when American John Cleves Symmes Jr. loudly proclaimed his idea that both the northern and southern poles contained entrances to this hidden interior world. These soon came to dubbed "Symmes holes" and captured popular imagination ... if not exactly scientific acclaim. Though Symmes set about on a lecture tour and gained a few notable followers (including former president John Quincy Adams), he never managed to secure funding for a polar expedition. Instead, Symmes died in Ohio in 1829. His son, Americus, eventually had a monument placed on his father's grave, complete with a hollow globe.

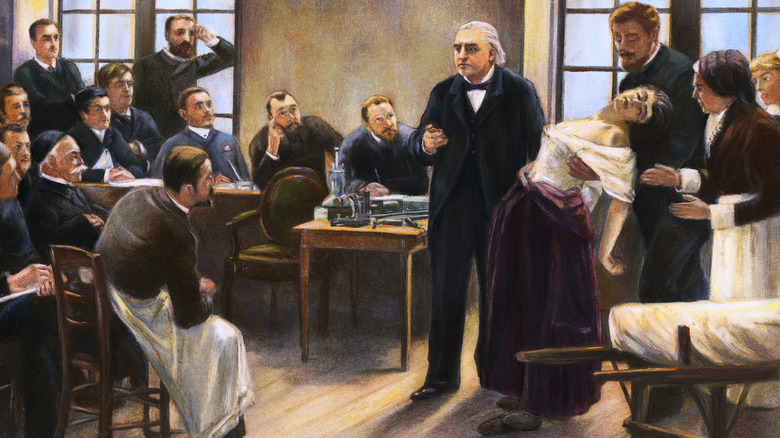

Hysteria was still considered a legit medical diagnosis

For most of history, being a woman in need of medical attention was a pretty difficult place to be. One of the worst offenders is quite possibly the idea of hysteria. Like many notions still in vogue during the 1820s, hysteria had been proposed many generations earlier. People in ancient Greece even suggested that a person's uterus was somehow able to move around inside a body and cause all sorts of trouble. To keep someone's organs from being literally suffocated or crushed by the bothersome uterus, one might place offensive odors near the head (to scare off the womb, of course) and more pleasant ones at an individual's other end. Not everyone agreed with this; the ancient physician Galen pushed back against the idea, but he also thought that humans basically produced thinking juice he called "animal spirits," so don't give him too much credit.

Still, even with advances in medical science, doctors of the early 19th century still liked to blame all manner of women's health issues on hysteria. At least some, like Philippe Pinel, were advocating for being nice to female patients, though one gets a sense of paternalism from this sort of advocacy. At any rate, it was used as an excuse to block supposedly emotional, irrational, womb-plagued women from much employment and certain parts of society. Perhaps most shocking of all, hysteria wasn't officially struck down by most professional psychological societies until the 1980s.

The miasma theory of disease was in full swing

What exactly causes disease? Of course, if you asked this question in the first couple decades of the 1800s, you sure weren't going to hear a thing about germ theory. Sorry, you're trying to tell these learned doctors that teeny, tiny organisms are getting into your body and making you sick? Obviously it's yucky air, duh. Not that anyone back then called it "yucky air," exactly. Instead, they used the more complex-sounding term of "miasma." This theory, now one of the most famously disproven scientific theories in human history, once argued that illnesses were caused not by germs, but by airborne vapors. For instance, some argued that cholera cases in London accumulated in low-elevation areas because that's where the bad vapors tended to concentrate. (The actual cause was germ-rich water sources and poor public sanitation.)

John Snow, the celebrated British doctor and researcher who mapped out cholera cases in poor London neighborhoods, was one of the earliest scientists to suggest that contaminated water might have something more to do with public health problems than miasma. Yet, when he died in 1858, people were still skeptical of the idea.

Mesmerism was a controversial practice

Today, hypnotism treads a fine line between a silly little stage trick and a sometimes-accepted component of legitimate medical practice. Back in the 1820s, however, an earlier form of hypnotism was sticking around, much to some peoples' consternation. Known as mesmerism or animal magnetism, it was first championed by 18th-century doctor Franz Anton Mesmer. Dr. Mesmer essentially said that we were full of magnetic fluid and that a number of illnesses could be explained by problems in the body's magnetic field. It certainly shares some intellectual DNA with the concept of humoral medicine, but instead of bleeding or purging a patient, Mesmer and his followers claimed they could somehow manipulate the path of this mysterious magnetic stuff and make a person feel better. Mesmer enjoyed his greatest successes in upper-class circles, where rich, presumably bored women with little else to do flocked to his salon for quasi-mystical treatments.

Other doctors and scientists became skeptical of mesmerism fairly early on, especially when those well-to-do ladies behaved rather shockingly when under trance. (Treatment sometimes induced convulsions, swooning, and other behaviors many thought were best confined to the bedroom.) Yet, mesmerism stuck around, perhaps in part because of its controversial, almost rock-'n'-roll type of reputation. It made it across the Atlantic in the late 1820s, but Americans didn't start really cottoning on to the mesmeric trend until the next couple of decades when doctors — or maybe just quacks, as critics claimed — began writing and lecturing on the subject to audiences.

Mercury was an essential part of the doctor's kit

You hopefully have a helpful, if not frequently tested, fear of mercury. The stuff is a powerful toxin that, in its different forms, can wreak major havoc on one's nervous system, skin, eyes, kidneys, and more. But while modern exposure often comes in the form of mercury-laced seafood or industrial pollution, people in the 1820s might have been given mercury by their very own doctors. Throughout the Victorian era and even into the 20th century, doctors or patients might apply topical mercury solutions, ingest pills, or even inhale vaporized mercury, sometimes to deadly effect.

Abraham Lincoln himself might have been exposed to dangerous regular doses of mercury, which were a key component of the "Blue Mass" pills he took. Why chow down on mercury? Some now suggested that Lincoln downed them to combat the melancholia (depression) that reportedly dogged him throughout his life. However, he did stop taking the medication shortly after becoming president, as he is said to have noticed it caused emotional disturbance rather than treating it. Mercury was by then a long-established way to address mental illness, yellow fever, and syphilis, among many other maladies. It's clear others a few decades before Lincoln's time would have experienced the sudden rages and neurological symptoms that seemed to affect the future 16th president while he was ingesting Blue Mass.

Some thought electricity might have reanimating properties

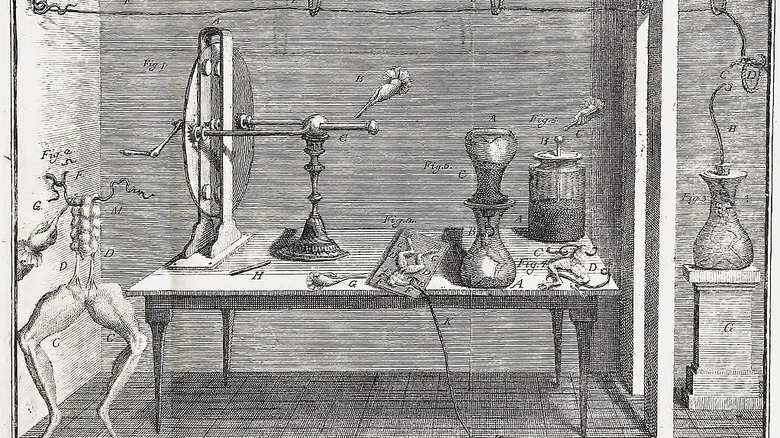

The image of Frankenstein's monster arising from a table in the midst of an electrical storm is a dramatic one, but it also has a basis in reality. Not a one-to-one comparison, mind you, but enough that you'll wonder what precisely the scientists of the 1820s were up to. At this point, a few had already been experimenting with mild electrical charges that made deceased subjects (including humans) twitch about in eerie, almost lifelike ways. This was known as galvanism, after anatomist Luigi Galvani, who first experimented with electricity and dead frogs in the 1780s. This theory was explored in experiments that were part science, part sideshow, with plenty of sparks and loud bangs to keep audiences fascinated. Author Mary Shelley almost certainly heard of it, though she wouldn't mention it until the forward to an 1831 edition of her novel "Frankenstein."

But while most seemed interested in learning more about how muscles worked under the application of electricity, a small number wondered if, just maybe, galvanism could bring someone back from the dead. (Hey, later scientists also wondered if dead people's retinas could hold onto images.) Scottish chemist Alexander Ure tried just that in 1818, though, as with any other similar experiment, nothing really happened in the reanimating department. Meanwhile, Danish scientist Hans Christian Oersted conducted research that demonstrated a very real connection between electricity and magnetism when he noticed that an operating battery affected a compass needle. Oersted published his results in 1820, kicking off research demonstrating that electromagnetism was a very real phenomenon.