Famous Military Leaders Who Were Really Weird People

To lead armies to war is an extremely serious undertaking, requiring discipline, experience, and an understanding of both the relevant military objectives and what may be possible under the circumstances. Therefore, few charges are more serious than those of military commanders, into whose hands soldiers place their lives and nations their fates. So it's all the more surprising, and sometimes even alarming, when the men (and occasional women) in charge of directing military actions are less war eagles and more odd ducks.

Whether they were conversing with saints, recalling their past lives, or taking just a bit too much mercury for "medicinal purposes," military leaders have occasionally pushed the boundaries not only of etiquette and tradition but also of rational human behavior. Some were able leaders and tacticians despite their foibles, while others were irredeemable goofballs who should never have been placed in charge of dinner plans, much less the lives of the fighters under their command.

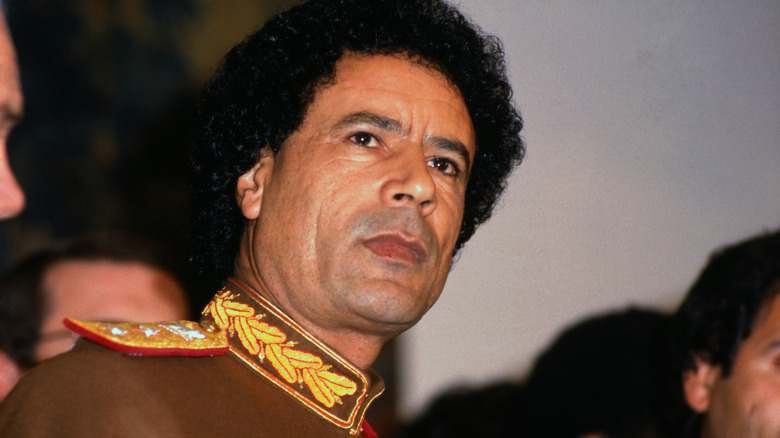

Colonel Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Gaddafi came to notoriety by ruling as the mercurial dictator of Libya for decades, but he was able to seize that role because of his military instruction. He began planning early to overthrow the Libyan monarchy, making connections as he passed through the country's military academy, and took control of the country while still in his 20s. As a leader, he was more persistent than successful as a warmaker, meddling in neighboring countries without achieving much until Gaddafi's overthrow and extralegal execution in 2011.

Among Gaddafi's many, many quirks, he was infamous for strange and grandiose statements, comparing himself to Abraham Lincoln and proclaiming Libya the only democracy in the world, a factoid that came as a surprise to many Libyans. He plastered his face all over Libya but was reluctant to have new pictures made, even trying to weasel out of having a photo made for a US visa by saying those involved could just use a shot of a billboard featuring him. (This gambit failed.)

Gaddafi also apparently had a crush on Condoleezza Rice, the former US Secretary of State. He made and played her a tribute video called "African Flower in the White House," about which Rice later said that she had been relieved it was not sexually suggestive. After his fall, rebels tossing his quarters found an album he had made of images of Rice, a sort of home-made "Tiger Beat" of one of the world's most powerful women.

General George Patton

Tough but fair general George Patton was one of the United States' key commanders in both world wars, spearheading the developing tank warfare program and smashing the Nazi armies in northern France in 1944. Denied a command against Japan and placed over occupied Bavaria after the war, "Old Blood-and-Guts" died shortly after the German surrender; Patton was killed in a car accident in December 1945. Prone to angry outbursts, a devout Christian, and an impeccable dresser even on the battlefield, Patton was easier to admire than to like — but he wasn't sent to Europe to make friends.

One of Patton's most striking eccentricities was his belief in reincarnation, which is not a mainstream Christian dogma, and which extended to claims that he knew details of his own past incarnations. He tended to come back as warriors and commanders, perhaps unsurprisingly. Per references in Patton's memoirs, personal statements, and even a poem he wrote, the general believed himself to have been with Alexander the Great at the Siege of Tyre; slain by Parthians as a Roman soldier; at both Crecy and Agincourt during the Hundred Years' War (on different sides), and with the French armies that streamed across Europe under Napoleon. Since the world continues to find itself at war, Patton may well have respawned, fought, and died again since his 1945 passing.

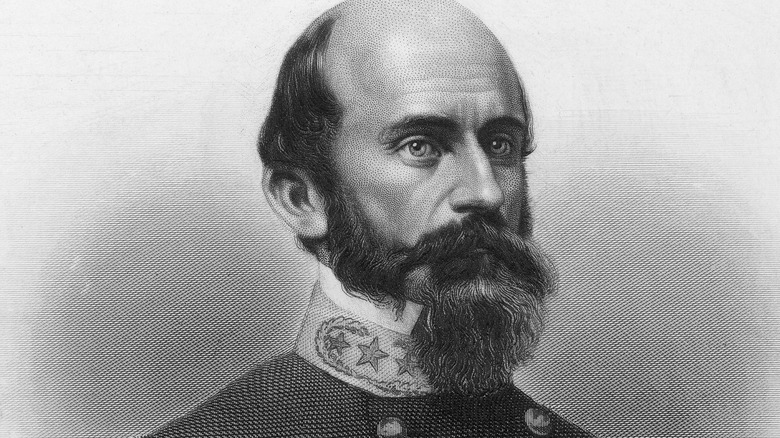

General Richard Ewell

The doomed Confederacy had only one truly lasting success: the creation of its own myth. Central to the "Lost Cause" idea and the many movies and books of varying quality that mourned it were the men who fought for the South, figures like ostensibly noble Lee, dashing Beauregard, and bitter-ender Stand Watie, the Cherokee chief who was last to surrender. But in the tier of Confederate commanders below these men, there were some less polished figures, and one of the oddest was General Richard Ewell of Virginia.

An odd-looking man with bug eyes and the massive beard that was popular in his day, Ewell's jerky movements were unflatteringly compared to those of a bird. The foul-mouthed general was cursed with an unusually high-pitched voice for a man, so when he went on angry, vulgar tirades, people instead found it funny, which is not ideal for a cavalry commander. An insomniac, he slept in odd positions when he did sleep, a habit probably exacerbated by his eventual loss of a leg.

Beneath his odd behaviors and the unpalatability of his cause, Ewell seems to have had a certain sweetness about him. He married late, to a widow, and never quite got used to it, introducing her as "my wife, Mrs. Brown." When he heard of Abraham Lincoln's death while en route to a prison camp just after the war's end, he cried and then did what generations of Southerners have been trained to do: he wrote a condolence letter, addressed to the victorious but bereaved General Grant.

Henry Paget, Earl of Uxbridge

The Battle of Waterloo was for all the marbles. Napoleon had come back from exile and was leading a renewed French army into the Low Countries, and the powers allied against him would either stop his advance or have to deal with the resurgence of a threat they thought they'd ended. In the end, Napoleon was defeated, Europe was saved, and the Earl of Uxbridge found himself with an unusual place in history.

During the battle, eight horses were shot out from under Uxbridge, but this run of luck (for Uxbridge if not the horses) ended when a cannonball smashed his right leg at the knee. The limb could not be salvaged, and a field doctor finished the French cannon's work with a battlefield amputation. Uxbridge reportedly joked throughout the operation, noting that the surgical knives felt blunt, but that he was happy to trade a leg for the major victory that was now apparent.

For his valor in battle, the remainder of Lord Uxbridge was elevated to a new title, the Marquess of Anglesey, and lived to be 85, describing his health as "one foot in the grave" when asked by anyone who had not yet heard this joke. The owner of the house in which the surgery had been performed kept the leg as a tourist attraction, complete with a tombstone for "Lord Uxbridge's leg" — presumably, as it had not been attached at the time of the upgrade, it could not properly be called the Marquess of Anglesey's leg.

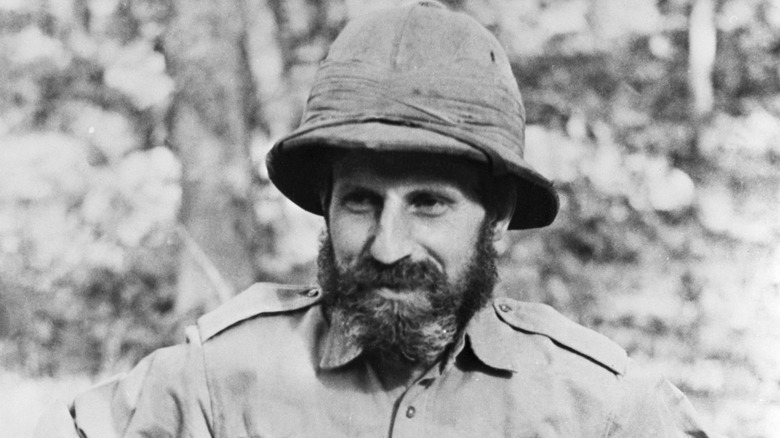

Major General Orde Wingate

By his death in 1944 at the age of 41, Orde Wingate had become a hero in three countries. Because these three countries were Israel, Ethiopia, and Burma, his legacy as a brilliant tactician and legendary eccentric is not as widely known in the rest of the world.

The moody and adventurous Wingate got his big break as an agent in then-British Palestine in 1936, where tensions were high between Jews who had been promised a state and the Arabs who lived in the double-booked territory. Wingate, openly on the side of the Jews, taught himself Hebrew and distinguished himself with his ability to organize anti-sabotage units and defend through strong offense. In modern Israel, he's considered the father of the Israel Defense Forces; critics have accused him of targeting civilians to advance his aims. When World War II began, he was reassigned to Ethiopia, where he helped undercut the Italian occupation and escorted Emperor Haile Selassie back to the capital, then Burma, where he organized anti-Japanese guerrillas until his death in an aviation accident.

He also used to walk around naked and hang a raw onion around his neck from a string, taking bites as the mood struck him. Probably more frustrating for those who served under him was that Wingate, a committed Christian, used to give impromptu sermons to his men, apparently despite their often being Jewish or Buddhist.

The Rani of Jhansi

In 1842, a young woman named Manakarnika married the ruler of a small Indian princely state called Jhansi, changing her name upon marriage to Laxmibai. She would become famous not under either of these names but under her title, the Rani of Jhansi, for her valor and death during a fierce struggle against British domination of India.

The Rani of Jhansi refused the veil and seclusion expected of royal Indian women, speaking directly to advisers and officials, both local and British. She wore a turban (which was "for men") and taught her court ladies to ride horses and fight. For her boldness and compassion for the poor, she was loved by her people, but not by the British, who conspired to snag her kingdom out from under her after the deaths of her husband and child. And so the Rani resisted. Famously declaring "I will not give up my Jhansi," she united her cause and her forces with the wider rebellion convulsing British India. She escaped a British sack of Jhansi and died fighting in the Battle of Gwalior, the last real skirmish of the Mutiny of 1857.

By dying so bravely, she gained the respect the British had denied her in life: The leader of the British forces at Gwalior, in a backhanded compliment, called her the only man among the rebels. Today, she is a major heroine of India, and even lent her name to the Rani of Jhansi regiment, an all-female unit active in the independence struggle in the 1940s.

Joan of Arc

It feels impolite, even borderline blasphemous, to call Joan of Arc weird, and yet she was. Her story is so familiar to many people that it's easy to overlook how bizarre it is: A teenage girl who claims to be communicating with dead saints shows up at a desperate king's camp, so they let her command troops. And then this completely untrained person, whose conversations with saints would probably be discounted as a form of mental illness in the modern world, reverses the tide of the war. As a result, she becomes one of the foremost heroes of a country that goes on to become a major military power with a world-spanning empire, as well as a saint.

Even beyond the truly fantastic broad strokes of Joan's story, details emerge that imply she was a strange person to go to war with. She was an artillery genius, despite almost certainly never having taken a geometry class, and her personal standard bore an image of Jesus sitting in judgment. Her first victory came when she bounced up from a rest; she and her men cleared the English out of several forts over the next few days, only letting the harassed English escape because they were retreating on Sunday.

Qin Shi Huangdi

In a few years, Ying Zheng rose from being the king of one of the several squabbling Chinese kingdoms to being the first emperor of all China, having used an innovative military technique called "using huge armies to turn anyone foolish enough to oppose you into a speed bump." He rebranded himself as Qin Shi Huangdi and announced that he'd been sent by God.

No sweetheart, Qin turned to consolidating the empire, burning books that did not support the official, approved philosophies, as well as undertaking infrastructure projects and minting coins to pull the empire more tightly together and more fully under his control. His harsh but successful reign has given him a mixed legacy, with different scholars preferring to approve of his accomplishments and disapprove of the means he took to get there.

Qin's death is what makes him an eccentric as well as an administrator and conqueror. He thought, or at least hoped, that he could achieve eternal life, an end he pursued by drinking, among other elixirs, mercury. That had the effect it usually does, and China's first emperor died at the age of 49. He was buried in one of the most lavish tombs ever constructed: 8,000 clay warriors stand guard over his remains, undisturbed until their rediscovery in 1974, joined by musicians, birds, and other people and animals rendered in clay and metal to please and serve the emperor in the beyond. Lest this charm you, know that he had the craftsmen killed to keep their work his alone.

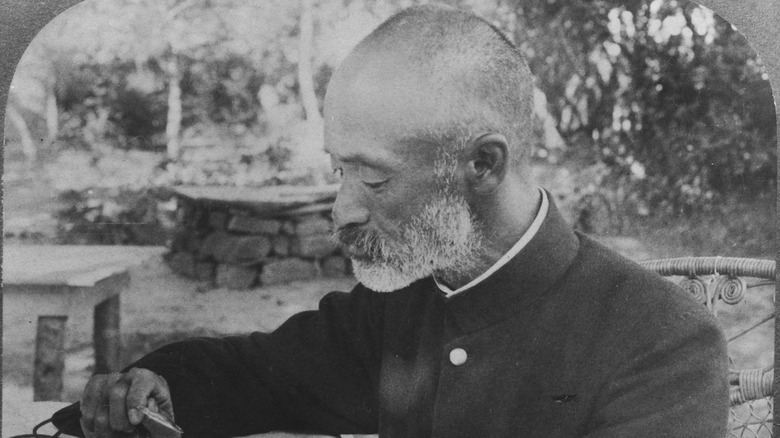

General Maresuke Nogi

Japan's Maresuke Nogi stumbled in the initial phase of his army career, being temporarily suspended for "drinking green liquors under scarlet lanterns." Nogi put such glamorous sins behind him, but suffered another blow during the 1877 Satsuma Rebellion, in which samurai revolted against the reinstated power of the emperor and the associated reforms. During battle, Nogi lost the standard of his regiment and was sentenced to death for the dishonor, only to be spared by the personal intercession of Emperor Meiji himself, who ordered Nogi to return to the army.

Decades later, during the Russo-Japanese War, Nogi lost many men in a successful assault on a Russian position during the war's final land battle. He asked for permission to expiate this perceived failing through dying by ritual suicide, which was again refused by the emperor, who instructed Nogi not to die while the Meiji Emperor was alive.

The Meiji Emperor died on July 30, 1912, which Nogi apparently saw as a green light to follow him. On September 13, Nogi and his wife both died by ritual suicide, according to the old Japanese ritual of seppuku. The Japanese public was divided: the samurai practice of following one's master into death was an important part of Japanese history, but it had also been outlawed as old-fashioned as far back as 1663. Nogi was subsequently declared a kami, a kind of Shinto spirit very roughly equivalent to a god or an angel, with a shrine that exists to this day.

King Mithridates of Pontus

Mithridates VI, king of Pontus on the southern shores of the Black Sea, was one of Rome's most dedicated enemies. Standing up to the rising and expanding Roman Republic was often an exercise in postponing the inevitable, and Rome eventually saw Mithridates dead and Pontus conquered, but it took 23 years and three "Mithridatic Wars."

Wily and savage, Mithridates intended to grow his kingdom and forged alliances with powerful neighbors like Armenia, convenient allies like pirates, and fellow Rome-fearers like Egypt. After a Roman consul sent to claw back some of Mithridates' conquests was captured, the king had molten gold forced down his throat to kill him, before encouraging a violent pogrom against every Roman and Italian who had settled in the region.

He was also obsessed with poison. Early in his reign, he began taking small doses of poisons in order to develop immunity to them; this actually can work under certain circumstances for specific chemicals. (Animal venoms maybe, heavy metals no.) He armed his men with poisoned arrows and lined the Roman invasion route with venomous animals, but there's only so much poison in the world and so very many Romans. Finally outfought by the Romans and with his own son refusing his calls for aid, Mithridates used the emergency poison he carried to kill his daughters to save them from Roman captivity before instructing a servant to kill him.

Empress Matilda

The widow of an emperor, wife of a count, and daughter of a king, 12th-century Empress Matilda might have chosen to sit around being rich. But when her cousin snatched away the crown of England after Matilda's father died, she fought. The resulting 19-year-long civil war known as the Anarchy saw Matilda pitted against Stephen's forces (which included his own tough-as-nails wife, another Matilda). Our Matilda almost won the war, even briefly occupying London, but she never sealed the victory.

She didn't pull off the win in part because she seems to have been a challenging personality, even controlling by the standards of medieval sexism. She was personally brave, escaping one siege by playing dead and another by dressing in white, climbing out a window, and running across a snowy field, but she was so rude and sure of herself that the Londoners themselves chased her away and let the war continue rather than accept her rule. She and her second husband notably hated each other, and she wasn't in England to accept her father's crown because she had rebelled against him in Normandy the previous year. England had to wait another 400 years for a ruling queen, and that was Bloody Mary.

Philippe, duc d'Orleans

Philippe, duke of Orleans, was the younger brother of France's Sun King, Louis XVI. He had a strange upbringing: Eager to avoid a repeat of the fratricidal civil wars of France's history, the boys' mother raised Philippe to be "effeminate," dressing him in girls' clothes in hopes of making him too soft to challenge his brother's authority. Arguably, it worked. As an adult, Philippe was openly bisexual, producing children with both of his wives but generally preferring the company of men. Distracted by gambling, bad boys, and clothes, Philippe had the unflattering nickname "the silliest woman who ever lived" and seemed to be no threat at all to his brother's authority.

That is, until war with the Netherlands broke out in 1672. Philippe turned out to be an unusually skilled military commander and a dogged fighter. He spent hours on horseback, risked his life, and was instrumental in the victory at the Battle of Cassel in 1677. Philippe was celebrated in Paris as a great warrior, which was exactly what his mother had tried to avoid. He was never again allowed to go to the front lines in any of his brother's wars, having once outshone the Sun King.