Weird Things About Presidents' Ancestors That Explain A Lot

You can't choose your family, a fact many U.S. presidents have known all too well. Jimmy Carter had a sketchy brother, Bill Clinton had a sketchy brother, and both of those siblings caused them embarrassment during their political careers. Others, such as Theodore Roosevelt and George W. Bush, had presidential children who were troublemakers and made headlines during their parents' terms. And if the most powerful men in the world couldn't keep their closest relatives in line, they certainly had no control over who their ancestors were and what they got up to.

Searching the family trees of the presidents reveals some shocking discoveries. Some engaged in acts of heroism, others were involved in notable firsts, and still others held beliefs that went against everything their future presidential relatives stood for.

All of these people, like the presidents who descended from them, were complicated individuals whose lives informed how those who came after them saw the world. Here are some weird things about presidents' ancestors that explain a lot.

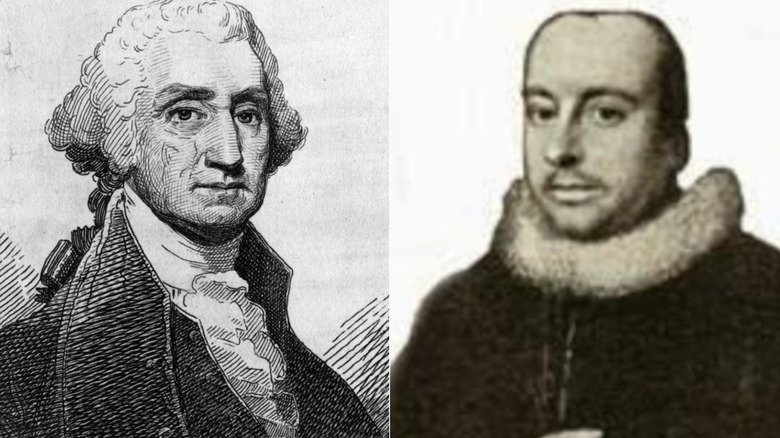

George Washington's ancestors fought a war on the side of the English king

While George Washington had a single mom who had a difficult childhood, his father was rich, and the future president was a member of the landed gentry. He also commanded the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War, so it's not surprising that his ancestors were also wealthy and involved in politics in England more than a century earlier. What is surprising is that when faced with choosing a side during the English Civil War, the Washington clan chose to support King Charles I (the Cavaliers) rather than Oliver Cromwell (the Roundheads), who was attempting to overthrow the monarchy.

The first English Civil War ended in 1646, and the Cavaliers were on the losing side. Charles I lost his head, and some of Washington's ancestors were also affected. Reverend Lawrence Washington lost his job. Others had money and land confiscated. In 1657, John Washington, George Washington's great-grandfather, left England for Virginia, hoping for better prospects.

In the late 1800s, genealogist Albert Welles wrote a book in which he claimed to trace 55 generations of Washington's ancestors all the way back to the god Odin. While that was not too fantastical for Welles, he found the thought of the Washington family supporting a king to be ridiculous. He wrote that he simply didn't believe the evidence that showed they were royalists during the English Civil War, because no relative of the first president, no matter how distant, could ever have held such unacceptable political beliefs.

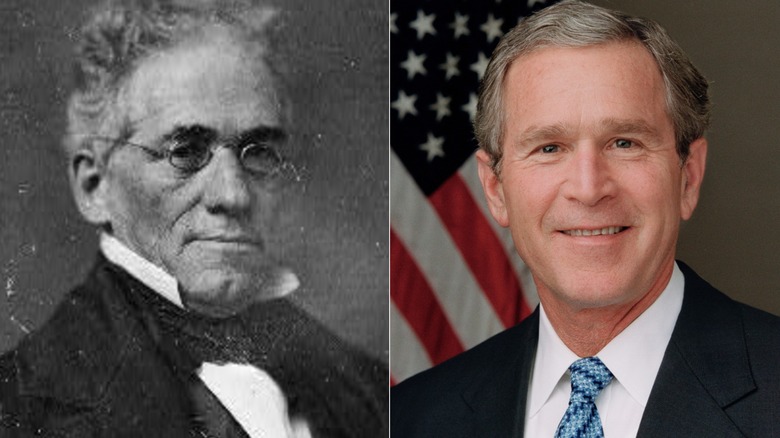

Abraham Lincoln's great-grandfather was overseer on two plantations

Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. This, in theory, although not in practice, freed all the enslaved people in the Confederacy. After the Civil War, all enslaved people in the United States were freed, with the last group on Galveston Island in Texas finding out about this on June 19, 1865. By then, Lincoln was dead, having given his life in the attempt to end slavery and keep his country united.

Lincoln's family tree on his mother's side was a bit murky, but there is some evidence that he believed he was descended from slaveholders. Before becoming president, he was a lawyer, and his law partner was William H. Herndon. Herndon would later claim Lincoln once admitted to him, "My mother was a bastard, was the daughter of a nobleman, so-called, of Virginia. My mother's mother was poor ... and she was shamefully taken advantage of by the man" (via the Northern Neck of Virginia Historical Magazine).

This might not be exactly true. There is a big question about who Lincoln's grandfather was, so it is impossible to know if he was rich enough to own a plantation and enslaved people. What is known is that Joseph Hanks, Lincoln's maternal great-grandfather, worked as an overseer on at least two plantations in Virginia during the Revolutionary War. This means Hanks was in charge of up to 80 enslaved persons, although we know from his will that he was not a slaveholder himself, at least at the time of his death.

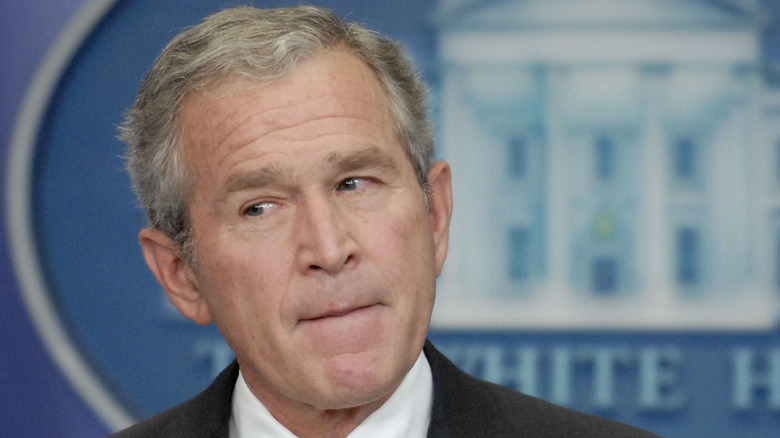

George W. Bush's ancestor wrote a biography of the Prophet Mohammed

George W. Bush infamously and controversially led the United States into the Iraq War in 2003. Anti-Muslim sentiment was high after the September 11th attacks, and even though Iraq had nothing to do with that tragedy, many uninformed Americans seemed to feel that all Muslims, or even just people who looked like they might be Muslim, were dangerous. Rampant Islamophobia was a dark stain on the Bush presidency.

A different George Bush, however, did know a lot about Islam, specifically the Prophet Mohammed. The cousin of the president's three times great-grandfather was the Reverend George Bush, and he was the first American to write a book about the founder of Islam. "The Life of Mohammed: Founder of the Religion of Islam, and of the Empire of the Saracens" was released in 1831. While he was ordained, the reverend did not spend much of his career in ministry. Instead, he studied the history and geography of the Middle East and became a professor of Hebrew and Oriental languages at NYU.

While the reverend's book had been out of print for ages, its connection with the then-president was discovered by the Egyptian Al-Azhar Islamic Research Academy in 2004. Censors demanded the book be banned in the country, seemingly on principle. However, after reading the book, they changed course the following year. While the reverend is not exactly kind to Mohammed in his biography, the censors allegedly decided his theology was acceptable.

Millard Fillmore's great-grandfather was forced to become a pirate

Millard Fillmore is not exactly remembered as a good president, or, more accurately, is not remembered as a president at all by most people. Historians consistently rank him as one of the worst commanders-in-chief the United States has ever had. Harry Truman summed up Fillmore's leadership style as one that always compromised because he was afraid to offend anyone, and someone who sat idly by instead of making the difficult decisions that would have been required in that pre-Civil War period.

The "do-nothing" president did not inherit his laissez-faire attitude from his great-grandfather, John Fillmore. A sailor since youth, during a voyage in 1723, John was unfortunate enough to meet a pirate ship captained by John Phillips. One of the men serving with Phillips knew John Fillmore, and a deal was worked out where John went with the pirates in exchange for the other sailors' freedom.

Captain Phillips was not a jolly pirate to work for, even by choice. The crew was terrified of him. John decided to take action, despite the extreme danger. After nine months with the pirates, at an opportune moment, he staged a mutiny along with three other prisoners. According to John's own account, he killed at least two members of the crew with an axe, including the captain. Once back safely in Boston, John and the other prisoners were charged with piracy but acquitted, and they gave evidence against the remaining pirate crew.

Jimmy Carter and Motown founder Berry Gordy are cousins through their enslaver great-grandfather

Jimmy Carter was born and raised in Georgia, part of the Deep South of America, where the Lost Cause was gospel when it came to the Civil War, and civil rights for Black people were still controversial. In his inaugural address as governor of Georgia in 1971, Carter said, "I say to you quite frankly that the time for racial discrimination is over. ... No poor, rural, weak, or Black person should ever have to bear the additional burden of being deprived of the opportunity of an education, a job, or simple justice" (via The Carter Center). As both governor and president, he made many decisions, both large and small, that advanced the cause of civil rights.

Carter's family tree is evidence of the complicated relationship between Black and white people in the South before and after the Civil War. The late president's maternal great-grandparents were the white couple James Thomas Gordy and Harriet Emily Helms. In 1863, Harriet gave birth to her fourth of nine children, James Jackson Gordy, the father of Carter's mother.

But James Thomas was a plantation owner and enslaver. Around a decade before Jimmy Carter's grandfather was born, James Thomas impregnated Esther Johnson, an enslaved woman he owned. Their child was named Berry Gordy. He would go on to have a son of the same name, who would in turn father another Berry Gordy, the founder of Motown Records. This makes the third Berry Gordy and Jimmy Carter second cousins.

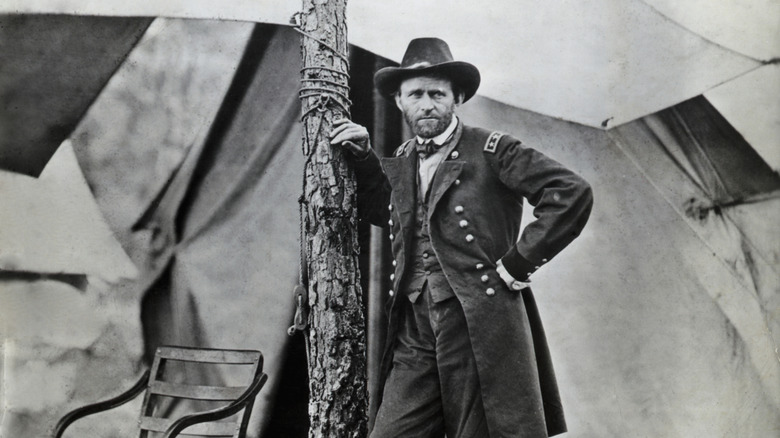

Ulysses S. Grant's ancestors served in multiple U.S. wars

When he was a young boy, Ulysses S. Grant told his father he did not want to go to West Point, but his father, Jesse Grant, insisted. As Jesse would later write to a newspaper, "The general comes of a good fighting stock" (via the Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library). This was true, and Ulysses was aware of it. In his famous memoirs, the first chapter is devoted to his ancestry, tracing back to the time when the first Grant landed in North America.

In just the fourth paragraph of "The Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant," the former president writes, "My great-grandfather, Noah Grant, and his younger brother, Solomon, held commissions in the English army in 1756, in the war against the French and Indians. Both were killed that year." Very little is known about these two men and their service, even to this day. Noah died on September 20, 1756, although his body was never found. Solomon was killed three months earlier.

More is known about the service of Ulysses' grandfather, also named Noah. The former president wrote of Noah Jr., "After the battles of Concord and Lexington, he went ... to join the Continental army, and was present at the battle of Bunker Hill. He served until the fall of Yorktown, or through the entire Revolutionary War." As one of the first to sign up to fight the British, it was said that Noah Jr. received his commission from George Washington himself.

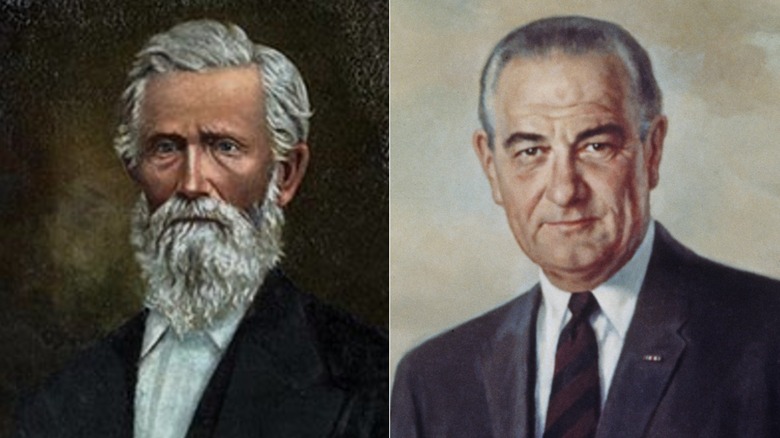

Lyndon B. Johnson's great-grandfather was a huge proponent of slavery

Lyndon Baines Johnson was a true Texan and identified strongly with his Southern roots. Considering the history of race relations in the South, you would hardly expect the president to make huge changes during his administration, like the landmark Civil Rights Act. And indeed, you don't need to go too far back in his family tree before you find a relative who would have been opposed to everything Johnson achieved that helped improve the lives of Black people in America.

The Reverend George Washington Baines, Johnson's great-grandfather, was ordained as a Baptist preacher in 1836. In the Antebellum period, the Baptists were pro-slavery. They used passages about slavery in the Bible to justify the institution, and in Texas, where the reverend eventually settled down, many of the state's most powerful and wealthy people were Baptist slaveholders. Reverend Baines was certainly among them. At the time that he became president of the Baptist-affiliated Baylor University in Waco, Texas, in 1861, he owned eight slaves.

The reverend made his thoughts on Black people clear in a piece in the Texas Baptist newspaper (via the University of North Texas) in 1861: "...to declare that they are equal in rights to [white men] ... is to declare what is positively absurd. They have not the capacity to understand or appreciate the rights, duties, and responsibilities of a free citizen ... God has given to us the right to buy and own slaves..."

William Howard Taft's ancestor is said to be the first woman voter in colonial America

The most famous myth about William Howard Taft is that he got stuck in a bathtub in the White House during his presidency, but it turns out that one of his most famous ancestors may have a much more significant myth built up around her. Depending on which historians you believe, the president was distantly related to the first woman ever to legally vote in the British colonies. As president during the suffrage movement, William had a mixed bag of opinions on women voting. He spoke at the National American Woman Suffrage Association convention in 1910, but admitted he was beginning to question the idea, although when he was younger, he had been all for the enfranchisement of women.

There is no question that William was the three-times great-grandnephew of Lydia Chapin Taft; the debate is around whether she voted or not. The story goes that in 1756, her husband, the largest landowner in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, had just died when she attended a town meeting. There, she was asked to vote on a measure in her late husband's place, in deference to the fact that she was now the town's biggest taxpayer. Lydia voted in favor of Uxbridge contributing more financial support to their militia for the French and Indian War. She would cast at least two more votes in the next decade.

While the historical evidence is thin, Massachusetts has officially recognized Lydia as the first woman to cast a vote in the colonies.

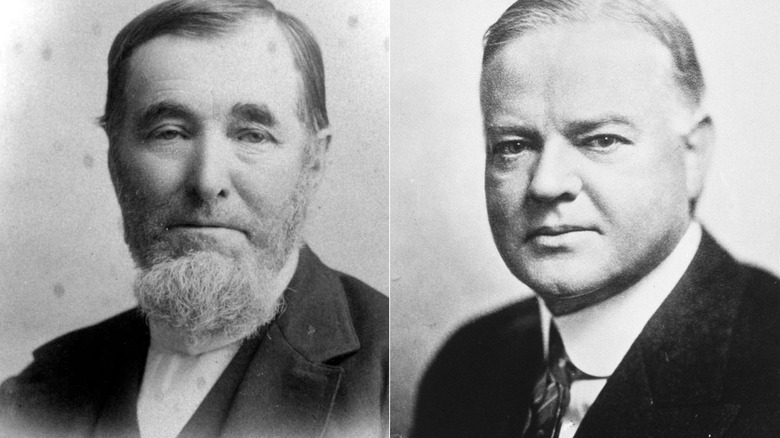

Herbert Hoover's grandfather patented an invention

Herbert Hoover was a terrible president, but he excelled in almost everything else he attempted in life. One of those areas was engineering. After earning a degree in geology, Hoover became a successful mining engineer and was often asked to comment on the profession. Speaking at Columbia University in 1951, he said, "The engineer has the fascination of watching a figment of his imagination emerge with the aid of science to a plan on paper. Then it moves to realization in cement, metal, or energy" (via the National Archives).

Herbert's father, Jesse Hoover, was a blacksmith, a profession that requires its own engineering and mechanical skills. But this family ability to tinker seems to have originated with the president's grandfather, Eli Hoover. Originally a farmer in Iowa, he had an idea for a contraption that would allow cows to fill up their own water troughs. On September 21, 1880, Eli was granted patent No. 232,499 for his invention.

The gift of invention lasted at least one more generation in the Hoover family, with the president's son, Herbert Jr., receiving a patent for a method to map the makeup of the Earth's crust using dynamite.

Richard Nixon's ancestor was a conductor on the Underground Railroad

President Richard Nixon was not exactly known for being truthful. According to The Washington Post, Harry Truman once said of his fellow politician, "Richard Nixon is a no good, lying bastard. He can lie out of both sides of his mouth at the same time, and if he ever caught himself telling the truth, he'd lie just to keep his hand in." Nixon saw this in a slightly different way. In an interview on French television, when asked about Watergate, he explained, "I was not lying. I said things that later on seemed to be untrue" (via The Washington Post).

Lying was a much bigger problem for Nixon's Quaker ancestors, especially during the first half of the 1800s. You see, Quakers were firmly against the institution of slavery, but assisting enslaved people fleeing to freedom could mean lying to the authorities. To avoid committing this sin, many Quakers chose not to assist these refugees.

Nixon's three-times great-grandfather, William Milhous, and his brother-in-law, John Vickers, found creative ways around this problem. According to The Kennett Underground Railroad Center, in 1818, Vickers told white men looking for escaped slaves, "It will be of no use to search my house, for I know there are no fugitives in it." This was true; the Black men they were searching for had just left. But by saying it in a suspicious manner, he caused the white men to waste time searching his home, giving the fleeing men time to get away.

Barack Obama is directly descended from one of the first known enslaved men in colonial America

The election of Barack Obama as the United States' first Black president after more than 200 years was deeply meaningful. Amazingly, genealogists managed to directly connect Obama to a man who some consider to be the first enslaved person in the British colonies. What is perhaps surprising is that Obama is related to the enslaved man not through his Black father but through his white mother.

There is a lot of debate among historians over when the distinctly American form of chattel slavery began in the British colonies. Some argue it was in 1619, when the first Africans arrived on a boat, while others claim that before the mid-1600s, those held in bondage in the colonies, both Black and white, were more comparable to indentured servants than chattel slaves.

For those who lean toward the second definition of an enslaved person, a Black man named John Punch is believed to be the first Black slave in America. Records indicate he was the first African to be enslaved for life as punishment for a crime in the British North American colonies. He and two white men ran away from the home where they were servants. While the white men were punished with a lashing, Punch was sentenced to "serve his said master ... for the time of his natural Life..." (via the "Minutes of the Council and General Court of Colonial Virginia"). Genealogists claim they've traced Obama's lineage to Punch through his mother, Stanley Ann Dunham. The former president is his 11-times great-grandson.