The Messed Up Truth Of Jim Jones

It was November 18, 1978, and the headlines were captured by a single event: a mass suicide that had taken place in the jungles of Guyana, and left 918 people dead. When US military personnel headed to the settlement called Jonestown in order to recover the bodies of the dead, what they found was "beyond imagination." What had happened was horrifying: the members of the Peoples Temple and the followers of the Reverend Jim Jones had drunk Flavor-Aid laced with cyanide ... but first, the adults gave it to the children. It wasn't all voluntary — they did it under the watchful eye of armed guards, and those who tried to refuse or flee were simply shot.

Recovery workers were grossly unprepared for what they saw. One said (via Time), "Can't sleep. Cannot get the small children out of my mind." Those workers ended up being interviewed as part of a study on the effects of PTSD on recovery workers and what's termed "secondary disaster workers" — and the study begins, "It is difficult to convey to someone what a week in a tropical environment can do to a [dead] human body."

Hundreds of the dead were ultimately interred in a cemetery in Oakland, and hundreds more friends and family members were left to wonder what had happened. Why they had done it. And why they had followed the man at the head of it all: Jim Jones.

The signs were there from his childhood

Getting to the heart of what happened at Jonestown means figuring out what made Jim Jones tick, and that's difficult. According to PBS, most of what we know about his childhood comes directly from him, speaking in retrospect. And, there's a caveat: he was what The Guardian described as a "liar and narcissistic psychopath," so it's next to impossible to know what's actually true... to a point.

We do know that his father was present but largely disconnected: James Thurman Jones was a World War I veteran, and according to The New York Times, exposure to gas had left him severely disabled. His mother was constantly working to support the family, and Jones would remember: "I didn't have any love given to me — I didn't know what the hell love was."

And here's where things get murky. According to Jones, he was always fighting bullies on behalf of other kids, feeding homeless people, and taking in stray animals. But what others remember of him is very different. Rolling Stone says those who grew up with him remember him conducting experiments on those same animals, and holding funerals for them. He held friends captive in a barn while he entertained them, and one friend remembered, "When Hitler committed suicide in April 1945, thwarting the enemies who sought to capture and humiliate him, Jimmy was impressed."

Jim Jones didn't start out as scary at all

That's the thing about cults — if they were scary from the beginning, it would be much harder to get people on board.

The first incarnation of the Peoples Temple was in an Indianapolis storefront, says NPR, and it was a huge deal — it was one of the first major, Midwestern churches that wasn't segregated. And what they preached, well, it sounded pretty good. They were all about ending the discrimination, homelessness, poverty, and starvation that plagued so many people. This was in the 1950s, and by the mid-60s, the church relocated to California (because Jones — like many — feared the seeming inevitability of a nuclear attack, and had read Eureka, California was one of the safest cities in the country.)

It was there where they really kicked into high gear, getting people in the door with some lofty promises. Take Teri O'Shea. She told The Atlantic that she was homeless when she was invited into the community, a place where everyone had food and a place to stay, where everyone was equal regardless of the color of their skin. And Jones put his money where his mouth was, preaching about civil rights, integrating churches and other public places, even building schools, health clinics, and kitchens to feed the needy. Sure, it's easy to judge in hindsight, but who wouldn't want to get involved with that?

Jim Jones captivated some of the most progressive organizations of the 1970s

The Peoples Temple wasn't originally a creepy cult, it was a force for good... on the surface, at least. According to one temple member (via Salon), Jones preached in such a way that he electrified the crowd — no matter who you were. "He made us feel special, like something bigger than ourselves." Another put it this way: "We were alive in those services. They had life, soul power."

The Peoples Temple set up in San Francisco's Fillmore district, and it was a time when urban renewal had left the neighborhood devastated and people looking for something to hold onto. It was at the same time when the progressive state legislator George Moscone was looking to run for mayor, and enlisted members of the Temple to campaign for him, which they did. At the same time, Jones made it clear he had enough dirt on Moscone to keep the new mayor firmly in his pocket (and whether or not that was true is less clear). Still, Jones ended up being appointed to the San Francisco Housing Authority.

And it wasn't just political leaders who walked hand-in-hand with Jones: AAIHS says he also wooed the Black Panthers, the Nation of Islam, and other progressive churches in the area. They became the champion of affirmative action and affordable housing, of equality, and of the disenfranchised.

Things were very different behind closed doors

Even as the political leaders of San Francisco shook Jones's hand in public, they were already starting to whisper. Things just didn't seem right: there were way too many security guards for a church, and there were some people who attended one service and never went back. Mayoral aide Dick Sklar remembered (via Salon) the family's maid had hated it. "... she came back and said it was the scariest place she'd ever been. They searched her, asked her questions. I had no idea."

Even as Jones preached racial equality, he kept close tabs on his 37-member "leadership council" — mostly white women, and a number were previous lovers. Meanwhile, Mother Jones says there was already plenty of unsettling things going on. Among the Peoples Temple membership was a large group of black women over 61-years-old and between them, they gave $36,000 of Social Security money to the temple each month.

And those who worked closest with Jones said that in hindsight, they should have known something wasn't right. Moscone press secretary Corey Busch had this to say about their ally: "I was at every meeting that Jim Jones ever attended with the mayor. I can tell you that after every one of those meetings, the reaction was, 'This is one weird bird.' [...] You couldn't predict Jonestown, but he was definitely weird. In retrospect, maybe we should have seen that, but we didn't."

Jim Jones made sure there was no way out

It's easy to ask: "How?" A big part of that answer is control, and according to Crime + Investigation, Jones made sure he had plenty of that — starting with his holier-than-thou image, one that helped persuade people to look past the shady stuff. One of the things he preached was the idea of giving back, and it was under this guise that he convinced his followers to submit to hours and hours of manual labor, fueled by meager rations. The result was exhausted, hungry, and obedient people — particularly those who, in 1974, labored to clear the Guyana jungle away from what would become the Jonestown settlement (via The Conversation).

Then, there was the blackmail. Teri O'Shea told The Atlantic that members signed blank papers Jones called "compromises." He made sure he had something on everyone; blackmail was common, fueled by secret recordings and often using children as leverage. Parents might leave... but they weren't leaving with their kids, and most parents would cave.

After the Peoples Temple moved to Jonestown, violence and abuse became commonplace. Members were broken already, and Jones used everything from public beatings to solitary confinement to make sure everyone was in line. Members told stories of beatings, staged boxing matches, sexual assault, electroshock, and public humiliation... all confirming that he was in charge.

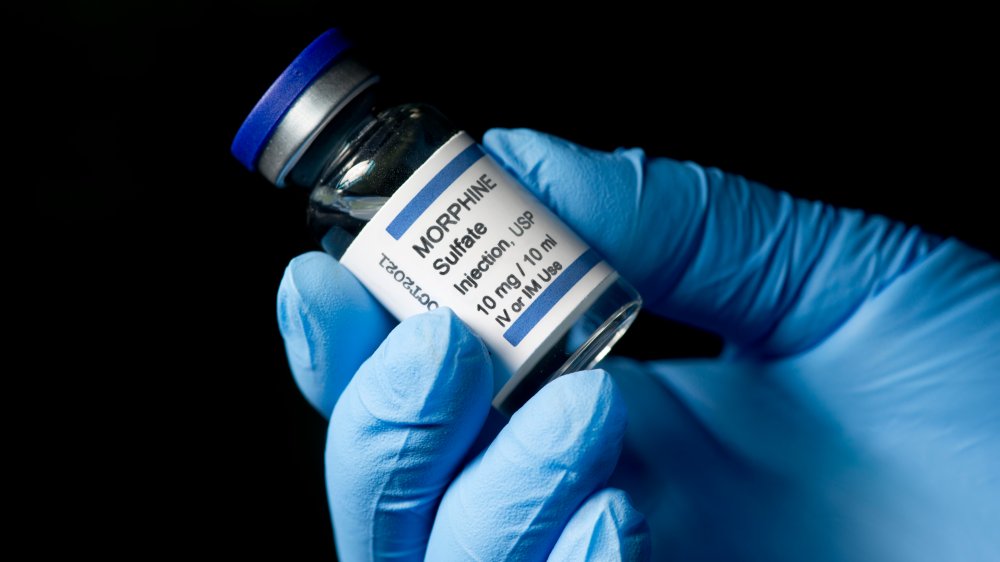

Jim Jones opted for drugs to control those who followed him

Dale Parks was a therapist and nursing supervisor who lived at Jonestown during the settlement's last days, before fleeing with the group Representative Leo J. Ryan had brought on a fact-finding mission just days before the massacre. He told The New York Times that Jones frequently used drugs to control anyone who was showing signs of wanting to escape, but even he had been shocked by the thousands upon thousands of doses of morphine, Thorazine, Quaaludes, Valium, and Demerol that had been found in what was a literal drug warehouse.

Parks later said that anyone who showed signs of wanting to leave was confined to an 8-bed "extended-care unit," where they were treated with the aforementioned drugs until "no further behavioral problems were anticipated."

And drugs weren't just for Temple members, they were for Jones, too. According to NPR, he started out by taking amphetamines to fuel his 20-hour days, then sleeping pills to grab some shut-eye. Amphetamines, of course, cause paranoia, and given that Jones typically self-administered at two or three times the typical dosage, it's not hard to see where things would start getting scary. And those dark sunglasses? He wore those because his eyes were always red from the drugs he was taking.

He wanted everyone to call him Dad

Reporter Tim Reiterman was there in the last days of Jonestown, and he saw plenty of people who wanted to leave. Families were being torn apart: some wanted to go, others wanted to stay, and children were caught in the middle. And Jones, he wrote (via AP), considered them all his children.

He "...asked his followers to call him 'Dad,' [and] did not like to lose any of his 'children.' He said he considered it a failing on his part when he did."

According to San Diego State University's Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple, the term started out as "Father" or "Father Jim" in the same way a priest might be called father. It was a religious term rather than a familial one, but as the years went on, his followers transitioned to "Dad." By 1977, Jones' paranoia had deepened and he — along with around 1,000 followers — made the move to Guyana. Why? Outsiders were getting suspicious that there was more to the Peoples Temple than met the eye, and according to History, Jones decided it was time to head to South America and build what he claimed would be a utopian society. It's about that time he made himself very clear: no one was to call him "Father" or "Dad" around non-members, because of how it sounded.

Jim Jones took his children with him

Jones' own family wasn't exempt from the orders to die: his adopted daughter, Agnes, and adopted son, Lew, both drank cyanide and died that day. So did his wife, Marceline. According to NPR, there are tapes of their last moments, where she screamed, "You can't do this, you can't do this."

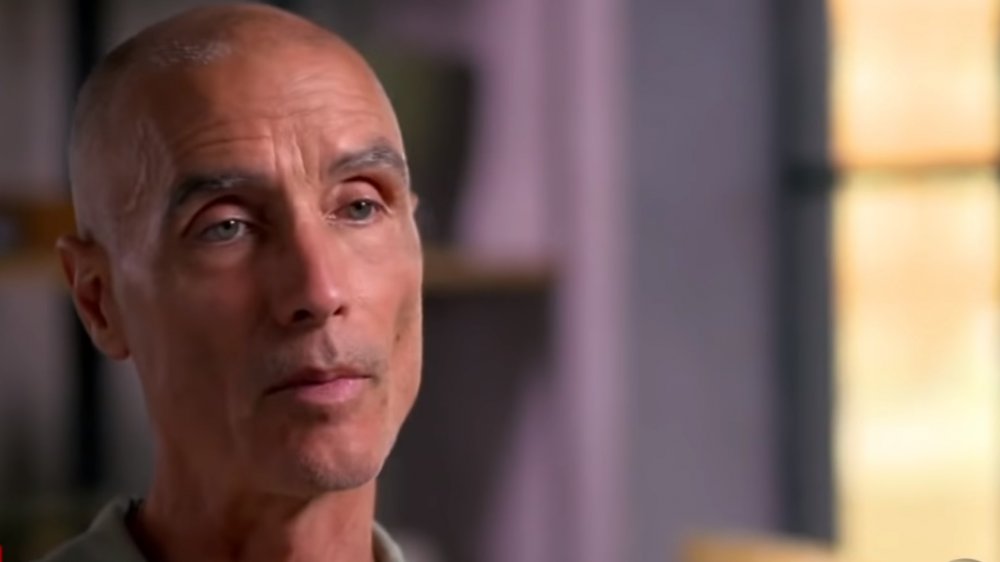

There were three sons, too, that were in the capital city of Guyana when Jones gave the orders. Stephan Jones (pictured) spoke with Haaretz, and told them how he had heard the announcement and tried to stop what he knew people were going to do. But it was already over. That included his father — Jim Jones died that day, too, not from poison, but from a single bullet to the head.

And what is his take on his father? "So it was not this grand march to death, far from it. We didn't see that coming. [...] we never felt he would go through with it because we saw him as such a coward." Stephan's also said that he and his siblings had thought it was all going to end very differently. "Dad was such a mess... He was so wasted most of the time. Everyone was waiting for him to take himself out. I don't know about the inner circle but many of us, and even my brother Tim, when he turned to my side, he wanted to kill my father, he was so angry."

He was obsessed with a child named John

Jim Jones didn't rule alone, and according to The American Spectator, he had a second-in-command named Tim Stoen. After a massive falling-out, Tim was actually mentioned on the now-infamous Jonestown death tape, when Jones declares, "Stoen does not get by with this infamy, with this infamy? He has done the thing he wanted to do, to have us destroyed."

Tim and his wife, Grace, joined the Peoples Temple in the late 1960s. Then, in 1972, they had a son named John. But here's the thing — the Peoples Temple believed that children should be raised communally, and parents gave up most rights to their children. Grace left the organization in 1976, Tim left in 1977, but when the Peoples Temple moved to Guyana, they took little John with them. Even though the courts ordered he be returned to his mother, Jones refused under the oft-repeated sentiment: "We'd rather die than have [John] ever taken, all of us."

When the Stoens headed to Guyana to try to get their son back they stayed in Georgetown while the rest of their party — including Rep. Leo J. Ryan — headed to Jonestown. They were still there when Jones declared it was all their fault, then ordered suicide. John was among the first to die, saying (via the Los Angeles Times), "I don't want to die. I don't want to die."

Jim Jones ran practice suicide drills

Jones wanted to make sure he had complete control, and when he issued the orders to drink the cyanide-laced punch on that fateful November 18, it wasn't the first time his followers had heard the order. Teri O'Shea told The Atlantic that she knew things were getting serious when Jones started running "revolutionary suicide practices" he called White Nights. The call would go out over the loudspeaker, and he would insist that their lives were in danger. When everyone gathered, he would spin the tale: Americans were being herded into concentration camps, people were coming to kill and torture them, they were coming through the jungle... it was time to drink. They were handed drinks, told they were laced with cyanide, and they drank.

"And then Jim would just start laughing and clapping his hands. He'd tell us it was a rehearsal and say, 'Now I know I can trust you.' And then, in the weirdest way, he said, 'Go home, my darlings! Sleep tight!'"

November 18 was one of these White Nights, but it was the real thing. A recording device on Jones's "throne" preserved the entire thing, says The Washington Post, and no, not everyone went willingly. The tape is 45 minutes long, and when it ends, followers can still be heard arguing and fighting for their lives.

Murder or suicide?

The events at Jonestown are often said to be a mass suicide, but it's not entirely clear that's what it was. Certainly, some drank the poison, but there's an argument that says Jones was responsible for murder.

Odell Rhodes is the only survivor who saw the ritual begin, and later said they were handed cups by a doctor. "They started with the babies," he said (via The Washington Post), recounting how mothers gave the poison cocktail to their babies before drinking it themselves. But did they actually have a choice? Rhodes said that there were plenty of those who tried to escape, only to run into a ring of armed guards.

Julia Scheeres, author of A Thousand Lives: The Untold Story of Hope, Deception and Survival at Jonestown, says (via History) that contrary to the popular belief that everyone committed suicide, it was more akin to murder. Jones gave them no choice, surrounding his followers with guards holding guns and crossbows, and orders to kill those who refused. And thanks to the practice runs, he knew who was likely to refuse, and those people were lined up first. Some who didn't drink were injected with the poison, and many thought it was just another drill... until the children started to die.

The scale of the tragedy was epic

The phrase "drink the Kool-Aid" has gotten so overused that it's become this weird entry in pop culture. And that makes it difficult to remember, sometimes, that Jim Jones wasn't a punchline — he organized (and forced) what the Houston Press notes was the "largest non-natural disaster loss of civilian life" for US citizens. It was a record that would stay in place until September 11, 2001.

It's easy, too, to write off the victims as being every bit as fanatical as Jones. But when Jamilah King found out (via Mother Jones) that her mother had lost a friend to the Peoples Temple, she realized that the people who had lost their lives were incredibly ordinary. They were a cautionary tale, a warning that anyone could get so wrapped up in an idea — especially an idea of creating their own "Promised Land," a "colorblind utopia." Every victim was someone, and every victim had someone back in the States who listened to the news of Jonestown with the ever-growing feeling of dread.

After researching the lives of those who died, she wrote, "I came away from all of this with a deeper appreciation for just how average Peoples Temple members seemed. I went into it thinking that I'd find people who were misunderstood, maybe, but also brainwashed. Their inclination to be part of something was ultimately misguided, but nonetheless, it was human."