The Tragic Real-Life Story Of The Who

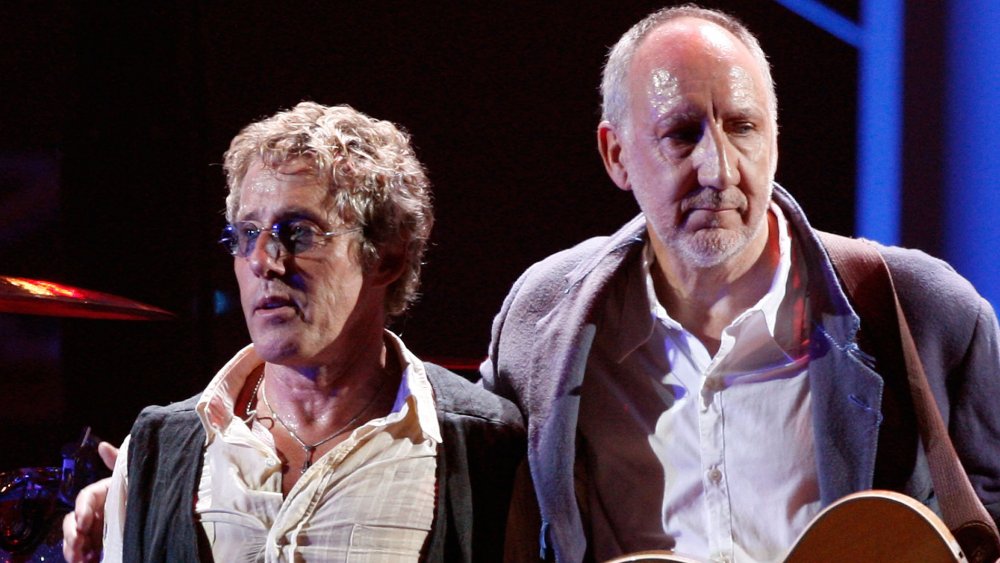

There are few bands as iconic, or which boldly loom over the rest of rock history, as The Who. After the poppy Beatles and bluesy Rolling Stones began the "British Invasion" of the 1960s, The Who wrote a new chapter, showing that rock could (or should) be incredibly loud, fist-pumping, and full of both rage and soul. The English foursome found a magic formula with the prototypical rock showman in Roger Daltrey, the emotive guitar work of Pete Townshend, the thundering bass lines of John Entwistle, and the acrobatic drumming of Keith Moon. Along with popularizing the "rock opera" with "Tommy" and "Quadrophenia," The Who added a number of songs to the classic rock canon, like "Baba O'Riley," "Won't Get Fooled Again," "I Can See For Miles," and "My Generation."

But while the music of The Who has brought delirious joy to countless millions, the band members' journeys to legendary status have been besieged by shocking and unexpected deaths, public disasters, violence, and destruction. Here are the worst things that have ever happened to The Who.

Pete Townshend's terrible childhood

Young Pete Townshend spent the first few years of his life in a West London area hit hard by German bombing raids in World War II, which ended just a few months after he was born in 1945. Death permeated daily life. "When I was four I lived in a house where 12 people had died," he told The Daily Telegraph. "We played in bomb sites, we'd find bits of bodies, skeletons, and watches every day."

When he was five, his parents split up and sent him to spend two years with "Granny Denny," his maternal grandmother. Life with grandma was "a f***ing nightmare," he told Rolling Stone. His father would send money each week, and Townshend "would go to the shop with my grandmother and buy myself a toy and she would take the toy and put it in a cupboard. Then when my mother came to see me, my grandmother would make me get all the toys out as though I'd been playing with them." Townshend's relationship with his grandmother is "the only bit of my life that I haven't been able to make any sense of," he said in "Minstrel's Dilemma" (via "Who Are You: The Life of Pete Townshend"). "If I was able to go into regressive hypnosis and either find some terrible trauma or nothing at all, it would be equally damaging to me as an artist."

Roger Daltrey was a troubled teen

Like Pete Townshend, Who singer Roger Daltrey was also born in England toward the end of World War II. The immediate decades after were tough for British working-class families, like Daltrey's, what with a lack of jobs and continued food rationing. According to the future rock star's memoir "Thanks a Lot Mr. Kibblewhite," he was a tough teenager prone to starting fights, making trouble, and bugging teachers. On his 15th birthday in 1959, he was expelled from school. "It had probably been on the cards for a while," he wrote. "I'd been caught smoking. I'd been caught playing truant. I was disruptive in class because I just wanted to be left alone by these teachers."

But the instigating incident that caused his headmaster (the "Mr. Kibblewhite" to whom Daltrey wryly alludes in the book's title) to toss him out was when he brought his air rifle to school. (The reason: "We were kids, and I was a kid who didn't like rules, and one of the rules was that you weren't allowed to bring air guns to school.") In the locker room after soccer practice, another kid grabbed Daltrey's gun and fired it. The pellet ricocheted off a wall and into another kid's eye, which never worked again. The student who actually fired the gun wasn't punished, while Daltrey, as the owner of the gun, received six smacks to his rear end as well as expulsion.

Roger Daltrey was fired for punching Keith Moon

The Who experienced its commercial breakthrough in 1965, when its singles "Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere" and "My Generation" hit the top 10 in the United Kingdom. The band was on its way to fame and fortune, but it almost all came to an abrupt end.

The Who experienced a frustrating chain of events while on tour in 1965 and 1966. Fans mobbed Daltrey at one show, hurting his back, on another stop the band's gear-filled van was stolen, and a show in Denmark was cut short after a few minutes when the crowd rushed the stage.

Keith Moon's substance abuse problems were also getting worse, and when Roger Daltrey discovered Moon's cache of intoxicating pills he flushed them down a toilet. Moon, wielding a tambourine, confronted Daltrey, but the singer quickly took care of the situation by punching his drummer right in the nose. "It took about five people to hold me off him," Daltrey said in "Roger Daltrey: The Biography." "It wasn't just because I hated him, it was because I loved the band so much and thought it was being destroyed by those pills." Pete Townshend and John Entwistle believed Daltrey had not behaved properly, and fired him. The departure didn't take — after the band's managers explained that losing its distinctively-voiced lead singer would be bad for business (and doing one show without Daltrey) they welcomed him back.

Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend almost killed each other

While getting ready to hit the road in support of "Quadrophenia" in 1973, MCA Records ordered The Who to make a promotional film. That ate up time Roger Daltrey rather would've spent on actual music-related tasks, and when he mentioned to Pete Townshend how annoyed he was, the guitarist came unglued. "Pete, fueled by the best part of a bottle of brandy, went off like a firecracker," Daltrey wrote in his memoir "Thanks a Lot Mr. Kibblewhite" (via Vulture). "He was up in my face, prodding me. 'You'll do what you're f***ing well told,' he sneered."

Sensing a fight, the band's roadies held Daltrey back from physically retaliating, only for Townshend to prod them to release Daltrey. "'Let him go!' screamed Pete. 'I'll kill the little f***er.' They let me go." True to the spirit of his word, Townshend then heaved a guitar at Daltrey. "It whistled past my ear and glanced off my shoulder, very nearly bringing a much earlier end to The Who." Daltrey says he then "replied with an uppercut to the jaw." It knocked Townshend to the ground, where he cracked his head. "I thought I'd killed him," Daltrey recalled. Feeling immediate and immense guilt, Daltrey rode with Townshend in the back of the hospital-bound ambulance, holding his hand the whole time.

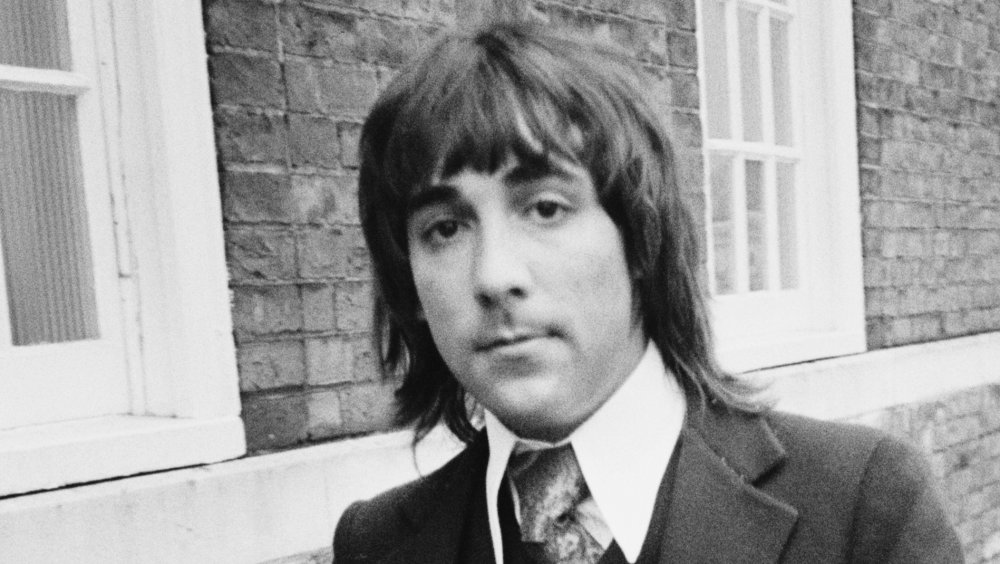

Keith Moon accidentally killed his driver

One night in January 1970, Keith Moon, and a group that included his friend and driver Neil Boland, attended the opening of a Hatfield, England, pub called the Red Lion. Also in the bar that night: a group of what Rolling Stone called "jeering skinheads." When things got too intense, Moon and his party tried to leave and made their way to the drummer's waiting Bentley. The locals threw rocks at the car, then attempted to flip it as Boland tried to drive away. In the chaos, Boland wound up outside of the vehicle and Moon took the wheel. As the fighting continued, Boland became caught underneath the car and was dragged for some distance.

Boland was pronounced dead at a local hospital, and Moon was charged with drunk driving, driving without a license, and driving without insurance. He was cleared of everything, with a judge telling the drummer that he "had no choice but to act the way you did and no moral culpability is attached to you."

Moon reportedly never shook the guilt of accidentally killing Boland. "One night when we were in bed he broke down and started to cry, calling himself a murderer," Moon's paramour Pamela Des Barres told The Sun, regarding his take on the night Boland died. "He would wake up screaming. It was so sad because it was obviously an accident but he blamed himself."

Keith Moon died while trying to overcome alcoholism

Even in the world of '60s and '70s rock music, where drinking hard and living it up were a matter of course, Keith Moon was known for his wild behavior fueled by his prodigious appetite for alcohol. For example: On his 21st birthday, he spent the whole day thinking, ran around a Holiday Inn in Michigan half-naked, fell down, knocked out part of a tooth, and couldn't safely receive anesthetic from the emergency dentist. In 1973, Moon was so loaded up on tranquilizers and brandy that he passed out behind his drum kit during a San Francisco concert. By 1978, Moon came to the conclusion that his imbibing had gotten out of hand. "I'm quite out of control," he told "Good Morning America."

And so, Moon attempted to quit drinking with the help of a doctor, who prescribed him Heminevrin (clomethiazole), a powerful sedative that helps alcoholics stop drinking by limiting withdrawal symptoms. On the evening of September 7, 1978, Moon went out to a club and ingested more than 30 of his pills. An overdose of clomethiazole can shut down the esophagus, which prevents vomiting. Moon choked in his sleep and died. He was 32.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

A stampede at a 1979 Who concert killed 11 people

The Who was set to play Cincinnati's Riverfront Coliseum on December 3, 1979, and the seating arrangement for the show was, like most rock concerts of the time, largely "festival" style — unreserved, standing-room-only, general admission. About 14,000 people would have to battle each other to get as close to the stage as possible.

Fans started to gather for the evening show at about 1:30 p.m., and by 6:30 p.m., a crowd of 8,000 aggressively pushed against the doors. It got worse when fans could hear The Who doing its soundcheck, and they got antsy — as well as cold, as it was 36 degrees and windy — unwilling to wait for the doors to open at 7:05 p.m. That restless crowd turned into a stampede — people got pushed, knocked down, lifted up, and trampled as thousands rushed to get inside the doors, of which only two out of 16 were fully open.

The concert proceeded normally, but just before the scheduled encore, The Who's manager, Bill Curbishly, told the band to do that part of the show quickly, because something very bad had happened. At the conclusion of the show, Curbishly told his clients that the pre-show stampede had proved fatal: 11 people died that night. A few weeks later, the Cincinnati City Council passed a law that banned festival seating at concerts, in the hopes of preventing another unspeakable tragedy.

Every member of the band experienced severe hearing loss

The Who earned its nickname. Labeled "the loudest band on Earth," the band actually once set a record for concert noise. The band's concert on May 31, 1976, in London reached 126 decibels, which is just slightly above the threshold for causing pain and injury to the ears.

Playing at or near those levels every night for decades left all three of the longest-surviving members of The Who with serious to severe hearing problems. Pete Townshend's tinnitus (a persistent ringing in the ears) got so bad that the band canceled a spring 2010 tour, and he now reportedly wears hearing aids in both ears. Townshend told the BBC that the late John Entwistle's hearing was so damaged that in 2000 he couldn't hear the rest of the band well enough to keep time with the music. At a 2018 solo show in Las Vegas, The Mirror reported that Roger Daltrey told the crowd he employs in-ear monitors and lip-reading to be able to sing along to the music as he is "very, very deaf."

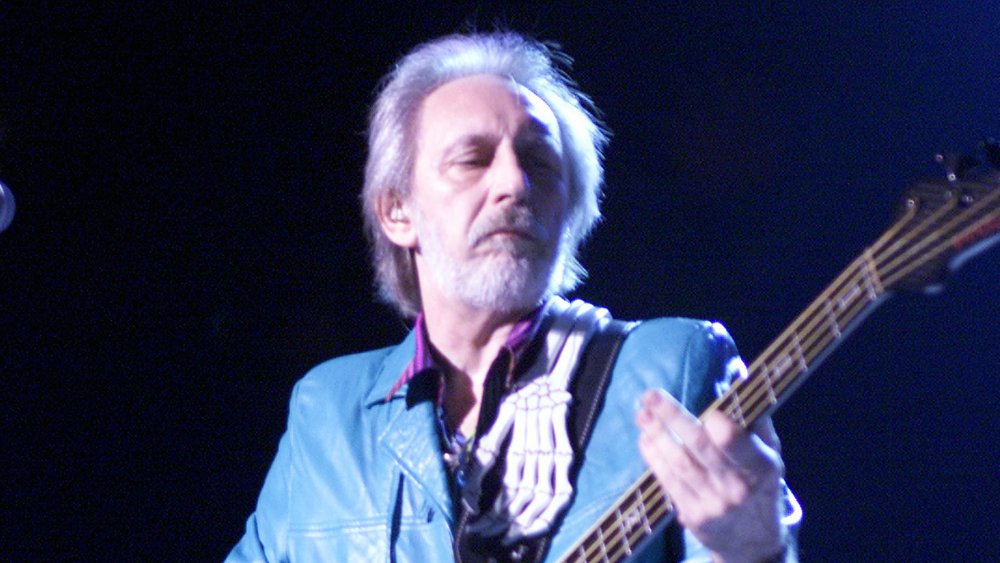

John Entwistle died

The Who recorded into the '80s and, from the '90s on, consistently toured. After a handful of dates in England, the band's 2002 tour hit the U.S., with the first concert scheduled to hit Las Vegas on June 28. That show didn't happen, because 57-year-old Who bassist John Entwistle died sometime in the night the day before. According to The Guardian, after spending the evening knocking back drinks with his bandmates, Entwistle entered his room at the Hard Rock Hotel and Casino at about 3 a.m. with an exotic dancer and self-proclaimed groupie named Alycen Rowse. When she awoke the next morning at about 10 a.m., she discovered Entwistle unresponsive, and his body cold. Her attempts to revive the bassist failed, as did those by paramedics.

An investigation by the Clark County medical examiner's office ruled that Entwistle died from a heart attack, triggered by cocaine consumed earlier in the evening, which was too much for his heart, weakened by an undiagnosed ailment, to handle. Following Entwistle's death, The Who continued as a duo, with hired and session musicians replacing the deceased other half of the band. Roger Daltrey and Pete Townshend were back on the road just four days after Entwistle's death.

Fire destroyed their master recordings

Universal Music Group is the biggest record company in the world, managing the catalogs of countless artists through the dozens of subsidiary labels it owns. The company stored the master recordings of thousands of albums (from the 1940s up through the 21st century) of which it controlled the rights in a vault on the Universal Studios backlot in Hollywood, California.

Tragically, a destructive fire broke out at the facility on June 1, 2008. And while black smoke from the incident could be seen around the Los Angeles area, Universal suppressed news about just what was on fire. It wasn't public knowledge until 2019 that the fire burned up 100,000 masters and 500,000 songs — a sizable chunk of the recorded music of the last seven decades. The original recordings — from which vinyl, CD, and digital versions derive — of many legacy acts, including Chuck Berry, Dolly Parton, Three Dog Night, Peter Frampton, Styx, Cher, and The Who, were lost forever.

Roger Daltrey nearly lost his ability to sing

For decades, Roger Daltrey was in possession of one of the richest, and most powerful voices in rock. His singing style was one part rasp, one part throaty wail, taking songs like "Baba O'Reilly" and "Won't Get Fooled Again" to loud, nearly-operatic heights. Singing that way night after night for years took a severe toll on Daltrey's vocal health. The Who took a lengthy break before recording the 1978 album "Who Are You" in no small part because Daltrey had to recover from throat surgery after suffering an infection.

In 2009, Daltrey played six weeks of Who concerts and found himself unable to hit the notes he could usually hit. Six weeks before the band played the Super Bowl Halftime Show, Daltrey elected to have surgery rather than risk losing his voice entirely. Daltrey told CBS News that he sought out Dr. Steven Zeitels and the Mass General Voice Center, where he was diagnosed with pre-cancerous dysplasia and underwent an operation. "I got depressed after surgery, during what I call the big silence, that's when I realized what it would be like to not have a voice," Daltrey said.

Daltrey still has to take extra-special care to protect his voice. Marijuana smoking is unwelcome at Who shows — Daltrey is so severely allergic to the fumes that they temporarily shut down his singing voice.

Pete Townshend struggled to clear his name

In 2003, the FBI led a global sting to reduce the distribution of obscene material featuring children and bring charges against the worst offenders. The U.K. part of the plan, Operation Ore, ensnared 1,600 people, among them Pete Townshend of The Who. Townshend told authorities that in 1999, he'd used his credit card to access a website purportedly containing illicit materials, because he suspected he'd been abused as a child, and thought seeing certain images might trigger repressed memories. "What happened is that I did not enter the website, I did make the transaction which I immediately canceled," he told BBC Radio 4.

Four months after receiving a citation from London's Metropolitan Police, who thoroughly investigated the musician's seized computer equipment, Townshend was cleared of all criminal charges. However, he was required to list himself on the U.K.'s sex offender national registry for a period of five years, because he'd accessed that illegal website.

If you or someone you know may be the victim of child abuse, please contact the Childhelp National Child Abuse Hotline at 1-800-4-A-Child (1-800-422-4453) or contact their live chat services.