The Untold Truth Of The First Woman To Run For President

At least in the patriotic imagination of its citizens, the United States of America is a place where anyone can grow up to be president. Of course, in practice, that's easier said than done ... especially for one group of Americans, for whom the realities of full citizenship and suffrage took far too long to materialize. The sad fact is, in its nearly 250-year history, the U.S. has never elected a woman to the highest office in the land. But it's not for lack of trying: As of January 2024, Nikki Haley's hat is currently in the ring, and in 2016, Hillary Clinton became the first nominee to top a major party's ticket. She wasn't, however, the first woman to run for president: for that, we need to turn over 150 years past to the early Gilded Age, and a woman called Victoria Woodhull.

Three women helped to pave Clinton's path to a nomination. In 1972, Shirley Chisholm became the first Black woman to seek the job; she made it onto the ballot in 12 primaries and received a respectable number of delegates' votes, despite the racism and sexism she faced. In 1884 and 1888, groundbreaking female lawyer Belva Lockwood ran for president at a time when women had not yet won the right to vote. Because of a technicality, some consider her the first female presidential candidate. But for all intents and purposes, that distinction should go to Victoria Woodhull, whose life story is so fascinating, her 1872 presidential run is just one curious chapter.

Named for a queen, but not raised like one

The radical early feminist who would eventually attempt to become the American President was, ironically, named after a queen known for espousing traditional family values. On September 23, 1838, baby Victoria Claflin was born to Anna Roxanna and Reuben Buckman Claflin, who went by either Annie or Roxie and Buck. Her mother may have been inspired by the recently crowned 18-year-old Queen Victoria, but Victoria Claflin's childhood was anything but privileged.

The seventh of 10 children, Victoria's youth was marred by transience and economic instability, exploitation, and possibly abuse. In the biography, "Victoria Woodhull: First Woman Presidential Candidate," author Jacqueline A. Kolosov writes of Buck: "He held more than a dozen jobs, but was not particularly successful at any of them." The family's only steady source of income was from the snake oil cures they peddled at "medicine shows" at which her mother would also sell her services as a psychic. The Claflins settled for a time in Homer, Ohio, but wore out their welcome with another of their father's schemes. When the grain mill the Claflins owned went up in flames, their neighbors suspected Buck of having set the fire himself in order to collect the insurance money.

Though Victoria's formal education lasted only three years, it was evident that she was bright and possessed an incredible memory. She also claimed to experience visions in which she communed with angels. Her mother believed her, but on the podcast "The History Chicks," hosts Beckett Graham and Susan Vollenweider hypothesize that these trance states — which sometimes included visits from figures like Napoleon or her recently deceased friend — may have been the result of loneliness or trauma.

Spiritualist or scammer?

Between her royal namesake and the numerology of her birth (lucky number seven), Victoria Claflin's superstitious mother had always imagined her daughter was destined for greatness. Victoria bought into the concept of herself as special, too, which may have driven her ambition. Once she began to exhibit the ability to speak with the dead, the Claflins attempted to turn that superstition into a self-fulfilling (and money-making) prophesy. Victoria and her younger sister Tennessee, or Tennie, were fashioned as child clairvoyants who could interpret the past, predict the future, find lost objects, cure illness, and deliver messages to loved ones from those who'd passed on. They were so successful, their act became the family's bread and butter.

The Claflins had a captive, paying audience because spiritualism and the occult — even amongst the more traditionally religious — were all the rage at the time. The popularity of seances, fortune-telling, and the like can be attributed to a confluence of historical coincidences. Photography and telegraphy were recent inventions; just as the Civil War was tearing people apart, the camera and the telegraph allowed them to see and hear their faraway loved ones. Those technologies seemed practically supernatural, so it stood to reason mediums could communicate with souls on the other side. Famously, the spiritualist movement extended all the way to Lincoln's White House: First Lady Mary Todd patronized their services.

She traded one conman for another

Throughout her young adult life, Victoria Claflin was subject to the whims of her mother and father, whom biographer Barbara Goldsmith describes as an itinerant con man, a thief, and an illegitimate, illiterate religious fanatic. In the 19th century, there were few options available to young women looking to escape unhappy home lives; marriage was often the most convenient.

A 15-year-old Victoria met 28-year-old Dr. Canning Woodhull in 1853, when he was summoned to treat her illness. There's disagreement as to exactly how and why the pair were wed. In "Victoria Woodhull: First Woman Presidential Candidate," Jacqueline Kolosov suggests Woodhull courted Victoria and impressed her parents with his degrees and connections to New York high society. According to this account, teenage Victoria was eager to become the wife of a doting and respectable doctor. Goldsmith holds that Victoria eloped with Woodhull to flee her father's abuse. And author of "Victoria Woodhull's Sexual Revolution" Amanda Frisken writes that the Claflins married her off to the doctor.

In any case, Canning Woodhull turned out to be more like Buck Claflin than Victoria could've ever imagined. His esteemed family history was a fabrication, as was his medical practice, which did not require a license at the time and amounted to little more than one of her father's quack medicine shows. Worse yet, he was a violent and philandering alcoholic and morphine addict. Victoria would escape Canning, too, in time, but not before she bore two of his children. The turmoil of her first marriage would color the political stances for which she became notorious.

Motherhood influenced her opinions

On New Year's Eve, 1854 (just over a year after she and Canning Woodhull were married), Victoria Woodhull gave birth to a baby boy named Byron Woodhull. Though Woodhull welcomed motherhood despite her tumultuous marriage, she was devastated to discover that her infant son was intellectually disabled and blamed his condition on her husband's vices. Again, there's a lack of clarity about what caused Byron's developmental delays. Woodhull — who was only 16 years old — at first believed Canning's alcoholism was the culprit. It's also possible that his physical abuse could've harmed the fetus, and since a perhaps-impaired Canning assisted with the delivery, it's just as possible that Byron's disability was the result of a birth injury.

Woodhull's perspective on the tragedy of Byron's birth would change slightly as she became a more public figure. She came to espouse the idea that flawed marriages produced flawed children. This theory (which was disproved by the birth of a healthy daughter, Zulu, in 1861) informed her feminist and scientific opinions. She'd later align herself with the eugenics movement, writing and giving speeches in favor of what is now considered a highly problematic ideology, but what was then a fairly popular and accepted concept.

Byron lived to 77 and depended on caretakers his entire life. Though his mother's views might indicate a coldness and distance from a contemporary perspective, that she never relinquished his care to the state during her lifetime (he was institutionalized after her death) speaks to her commitment to her son.

Free love, but it's not what you think

Besides her presidential run, the thing Victoria Woodhull is probably best known for is her reputation as an advocate of free love. It's a position that would complicate her political career, partly due to misunderstandings and guilt by association.

Woodhull became involved with the free love movement after she met Colonel James Blood, a Civil War veteran and fellow spiritualist. The two bonded over their shared beliefs, including the belief that they were meant to be husband and wife even though both were still legally married to other people. They divorced their spouses (that Woodhull kept her last name cast doubt on whether they'd actually tied the knot) and set off on their own with her two children. Blood encouraged Woodhull's freethinking and introduced her to what were then fringe social and political ideas.

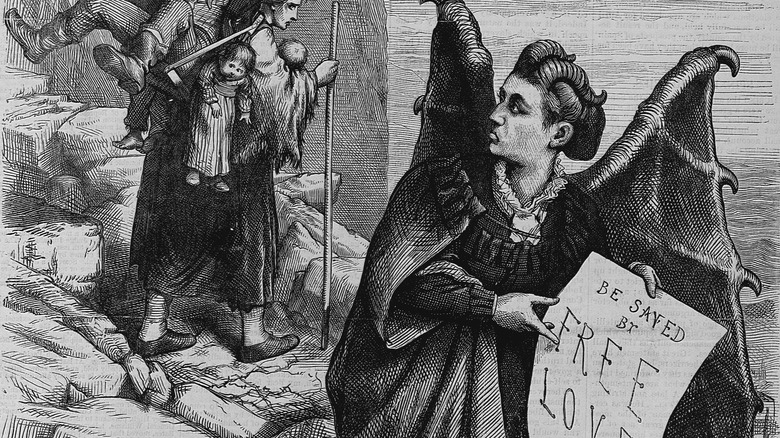

While there were free love practitioners — like the Oneida community — that rejected monogamy and even parental ownership of children, Woodhull's definition was something closer to second-wave feminism. Ultimately, she felt that without bodily autonomy and economic freedom, women were being coerced into marriage as a form of state-sanctioned prostitution. As a remedy, she championed marriage for love with the option to divorce, free public education (including sex education), family planning methods, and eventually the right not only to vote but to run for office. But these progressive stances were far ahead of their time, and the press vilified her most infamously with a cartoon in which she was drawn with bat wings and referred to as Mrs. Satan.

She had famous friends

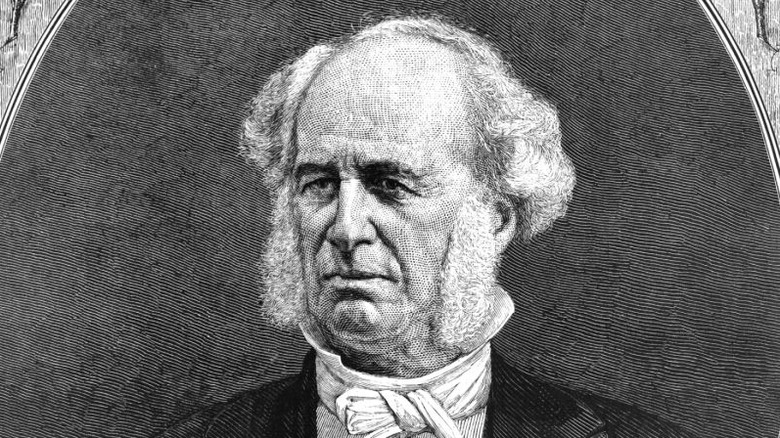

Victoria Woodhull reunited with her younger sister, Tennie Claflin, and the duo continued to offer their services as spiritualists, this time on their own terms. That's how they made the acquaintance of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt. The 73-year-old tycoon from the famed Gilded Age family became a favorite client and almost certainly a romantic partner to Tennie, to whom he may have proposed marriage.

Vanderbilt grew to rely on what he believed were the supernatural insights of Woodhull and Claflin (or, at least, he enjoyed their company), and he repaid the favor by teaching them what he knew about the stock market and helping them establish their own brokerage firm. Thus, the entrepreneurial sisters became the first female stockbrokers in American history. They leaned into their status as beautiful young women and clairvoyants; the novelty of their identity got them attention, and the notion that they could predict the future was a selling point for financial speculation. However, their early success had more to do with the inside information they gleaned from Vanderbilt.

With the fortune they made (which was at one point $700,000 in 1869 money) and with Vanderbilt's continued mentorship and patronage, the sisters bought a newspaper, which they renamed "Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly." Ironically, because their benefactor was the wealthiest man in the world and a living symbol of unfettered capitalism, they used their new role as media moguls to publish articles that supported left-leaning policies. In addition to free love and women's suffrage, the paper was the first to print Karl Marx's "Communist Manifesto" in English. It was rumored that the Commodore's heir, William Henry Vanderbilt, later bribed the sisters to protect his family's reputation and his inheritance.

She also made famous enemies

Victoria Woodhull and Tennie Claflin had an extremely powerful friend in Cornelius Vanderbilt, but as they accumulated power, they gained significant enemies. The burgeoning women's movement was mostly compromised of affluent women and their male allies; Woodhull, with her decidedly lower-class past and ties to the occult and free love movements, had trouble fitting in. Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of "Uncle Tom's Cabin," was a fellow female writer who personally disliked Woodhull and balked at the radicalism of many of her political ideas, particularly as they pertained to divorce. Though Beecher Stowe was stuck in an unhappy marriage, as Woodhull had been, she attacked the upstart activist in the press to dampen her influence.

Woodhull's new nemesis had a brother, Henry Ward Beecher, a well-known and well-liked preacher. Disdaining nothing more than hypocrisy, Woodhull used the same tactic to expose the religious leader's sexual impropriety. The scandal that became known as the Beecher-Tilton affair ignited when Woodhull leaked word of Beecher's infidelity during speeches, then published details in her newspaper. It was somewhat of an open secret that the preacher had been cheating on his own wife with Elizabeth Tilton, the wife of his friend, Theodore Tilton. Woodhull's exposure not only humiliated Beecher, but led Tilton to sue his pastor for criminal seduction.

In the end, Woodhull defeated her own purpose with her exposure of Beecher. He wasn't convicted, and her reputation took the bigger hit. The scandal overshadowed her own ambitions and drained her resources, and socially conservative forces coalesced in opposition to her. She was threatened with jail time for obscenity thanks to the newly enacted Comstock laws..

The first woman to run for president

As Victoria Woodhull's social and political views evolved, she crossed paths with other notable feminists of the day, such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. While they were organizing to build support for women's suffrage, Woodhull was arguing in front of the House Judiciary Committee (the first woman to do so) that she already had the right to vote. She interpreted the 14th and 15th amendments' use of the genderless terms "citizen" and "person" to apply to women. Though she didn't convince the powers that be, she did improve her standing amongst the more established suffragists.

Still, Woodhull didn't believe their efforts went far enough. Representation via the vote was one thing, representation via elected office was another. In 1872, Victoria Woodhull became the official nominee of the Equal Rights Party. She chose Frederick Douglass as her running mate, though he never formally accepted. Her campaign targeted women, freed African Americans, and blue-collar workers, promising better wages and working conditions, and equal protection under the law.

Woodhull — who was in jail on election day due to obscenity charges stemming from the Beecher-Tilton affair — never had a chance at winning the election. She was a woman, not yet 35 years old, and she didn't appear on any ballots. But that wasn't the point. Her candidacy was an act of protest. As her descendant Scott Claflin explained in an interview with NPR, "This was an era where a woman could not vote, could not enter a restaurant, a store, an establishment of any kind unless a man escorted her. It was controversial for women to do anything, but she had the foresight not to accept the way society was."

A complicated legacy

Victoria Woodhull had risen from poverty and obscurity to amass riches and national prominence, but after her failed presidential bid and her involvement with the Beecher-Tilton scandal, her star began to fade. Ever able to reinvent herself, she divorced her second husband, Colonel James Blood, and moved across the pond and became the wife of British aristocrat and banker, John B. Martin.

To be accepted into Martin's societal circle, Woodhull had to rehabilitate her reputation. The couple claimed ties to figures like George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, and Woodhull cultivated a new identity as a philanthropist. She and Martin remained married until his death fourteen years later, when Woodhull inherited his estate. She died on June 9,1927 ... seven years after women in America had finally secured the right to vote. She was 88 years old.

For all the contributions she made to key social and political movements, and for all the points at which her story intersects with other important characters from history, Victoria Woodhull isn't nearly as well remembered as many of her contemporaries. In "Mrs. Satan's Penance: The New History of Victoria Woodhull," Alena R. Pirok posits that perhaps this is because she was as much a tabloid figure as she was a radical and revolutionary. Woodhull's personal philosophies on topics ranging from abortion to eugenics to race are also difficult to categorize within a modern context. But, even if some of them come with an asterisk, she was undeniably a woman of many firsts, who impacted American life more than most people will ever know.