The Incredible Real-Life Story Of Shirley Chisholm

On Nov. 7, 2020, Kamala Harris became the first Black person, the first child of immigrants, the first woman, and the first person of Indian descent to be elected vice president of the United States. In a speech that night, she addressed, "All the women who worked to secure and protect the right to vote for over a century," saying, "Tonight, I reflect on their struggle, their determination and the strength of their vision... I stand on their shoulders." She especially acknowledged "Black women, who are too often overlooked, but so often prove that they are the backbone of our democracy."

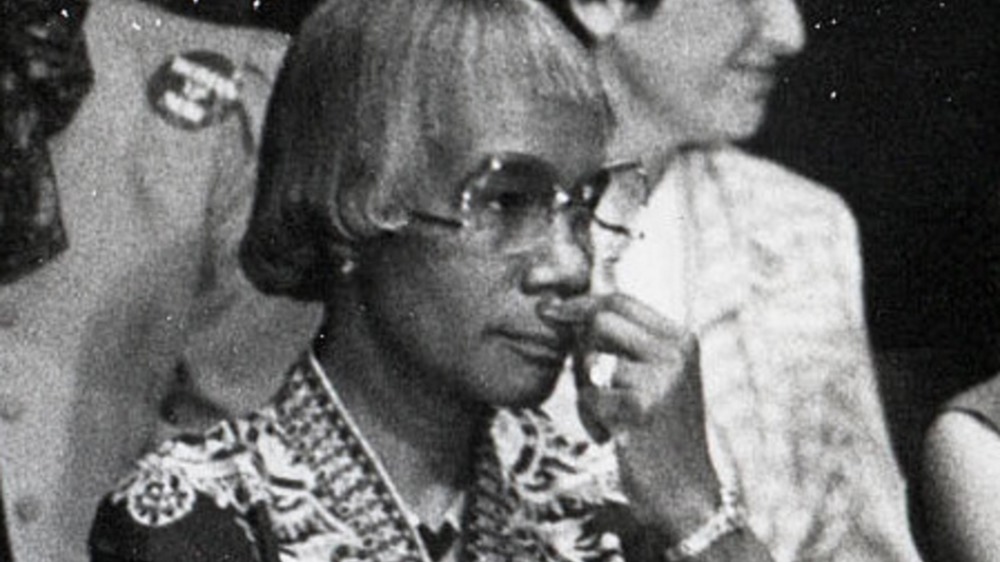

One of the people on whose shoulders Harris metaphorically stands is Shirley Chisholm. The daughter of immigrants from Guyana and Barbados, in 1968, Chisholm became the first Black woman elected to Congress, and in 1972, she became the first Black person to campaign seriously for the presidency on a major party ticket. Chisholm's slogan was "Unbought and Unbossed," and she maintained her fiercely independent spirit throughout her career, sometimes to her detriment. She sought to unite the marginalized, especially the poor, women, Black people, and native Spanish speakers, and to show them that they had as much right to run for president as the rich white men who consistently held office. She also knew how to reach across the aisle and play the political game. She didn't win the presidency but she made history — and helped others do so too. This is the incredible real-life story of Shirley Chisholm.

Shirley Chisholm was born in Brooklyn and raised briefly in Barbados

Shirley Anita St. Hill was born on Nov. 30, 1924, in Brooklyn, N.Y., to Charles St. Hill and Ruby Seale St. Hill. Her father, a baker's assistant and factory worker, was originally from Guyana, and her mother, a seamstress, was from Barbados. Charles was a devout follower of charismatic Jamaican activist and Black nationalist Marcus Garvey, and daughter Shirley Chisholm credited his political awareness with inspiring her own and her desire to lead. Her defiant spirit and self-confidence were obvious from a young age. "I would always have playmates that would be three and four years older than I am, and I would be the leader," she said.

The Washington Post reports that in 1928, Chisholm's parents temporarily took her and her two younger sisters to Vauxhall, Barbados, to live with their maternal grandmother while they saved money. They would later have a fourth daughter — Chisholm was the oldest.

On the island, Chisholm attended strict British-style schools (a legacy of colonialism). She later credited them for the strong academic performance she maintained throughout her education and her West Indian accent.

In her first autobiography, Chisholm wrote admiringly that her grandmother was one of the only people she would never dare to defy. According to NPR, she nurtured Chisholm's self-confidence. "She would say to me, you have a fighting spirit. Don't let anybody turn you around... I have a great deal of belief and confidence in myself."

Shirley Chisholm studied in Brooklyn and taught nursery school

Shirley Chisholm and her sisters returned to Brooklyn in 1934, and in 1939, she was accepted to the prestigious (and predominantly white) Girls' High School in Brooklyn. She became vice president of the Junior Arista Honor Society and graduated with a medal of excellence in French in 1942.

Chisholm was invited to attend Oberlin and Vassar colleges, but since her family couldn't afford either, she instead went to Brooklyn College, which had offered her a full scholarship. Some of her professors told her she was a natural fit for politics — it helped that she won a prize in debating. But Chisholm focused on other subjects, graduating cum laude with a bachelor's degree in sociology in 1946, with a minor in Spanish — a qualification which would help with her later political campaigns.

After college, Chisholm worked as a nursery school teacher for seven years, until 1953. She earned her master's degree in elementary education from Columbia University in 1952 and became the director of two New York daycare centers. From 1959 to 1964, she worked as an educational consultant for New York City's bureau of child welfare, according to the New York Times.

At the same time, Chisholm was involved in various local and national political groups, including the Seventeenth Assembly District Democratic Club, the Bedford-Stuyvesant Political League, the National League of Women Voters, and the NAACP. She co-founded the Unity Democratic Club in Brooklyn to mobilize Black and Latinx voters.

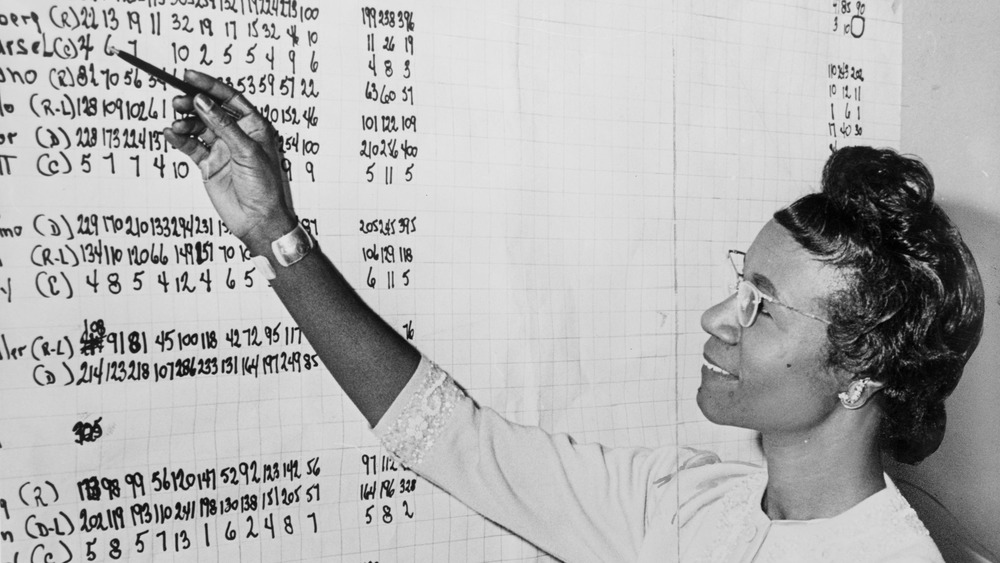

Shirley Chisholm triumphed in a race for the House of Representatives

In 1964, Shirley Chisholm became the second Black woman elected to the New York State Assembly. Four years later, redistricting opened up a seat in the national House of Representatives for her district of Bedford-Stuyvesant, and Chisholm decided to run for the Democratic nomination. She faced a tough race in the primaries against three more established candidates, including state Sen. William C. Thompson, who she believed was the preferred choice of the Brooklyn Democratic organization, according to the New York Times.

Chisholm took her campaign and her slogan "Unbought and Unbossed" to the streets. Her personalized style worked — she beat Thompson, her closest opponent, by just 800 votes.

Given that her district was 80% Democratic, the general election should have been a walkover. But Chisholm was up against James Farmer, an independent running as a Republican, who was famous as a civil rights campaigner. He'd co-founded the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and took part in the Freedom Rides. However, Farmer also held some outdated views on women, declaring that Black people needed a man in Congress, not a "little schoolteacher."

Chisholm fought back, arguing that it was time that a Black woman got a chance to act in government, that Farmer was an outsider who didn't even live in the district, and using her Spanish skills to directly address Hispanic voters. She won 67% of the vote, becoming the first Black woman elected to Congress.

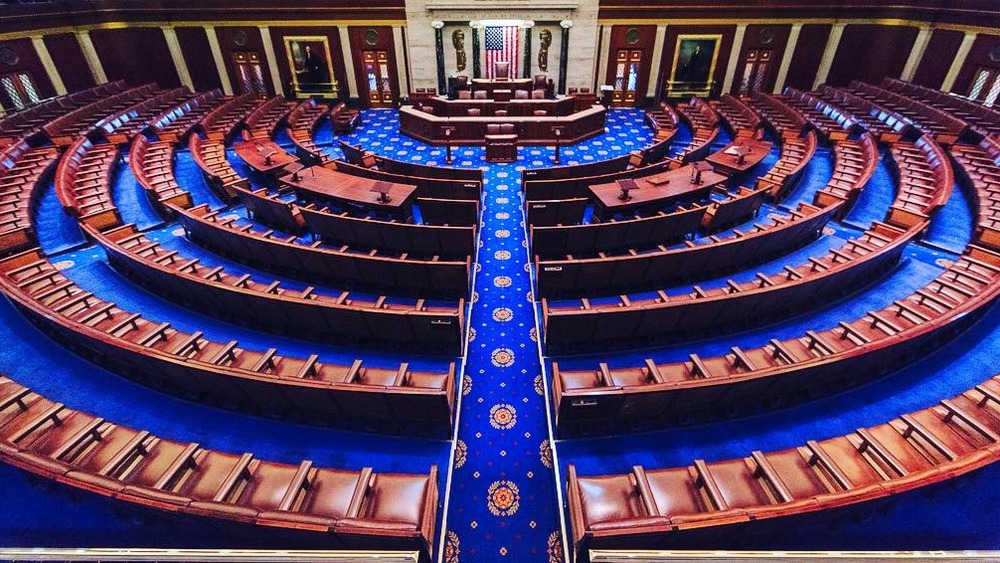

Fighting Shirley Chisholm came to Congress

Being the only Black woman in Congress was difficult. According to NPR, Shirley Chisholm later said that her colleagues wouldn't even sit with her in the lunchroom and for the first few months, "I was miserable."

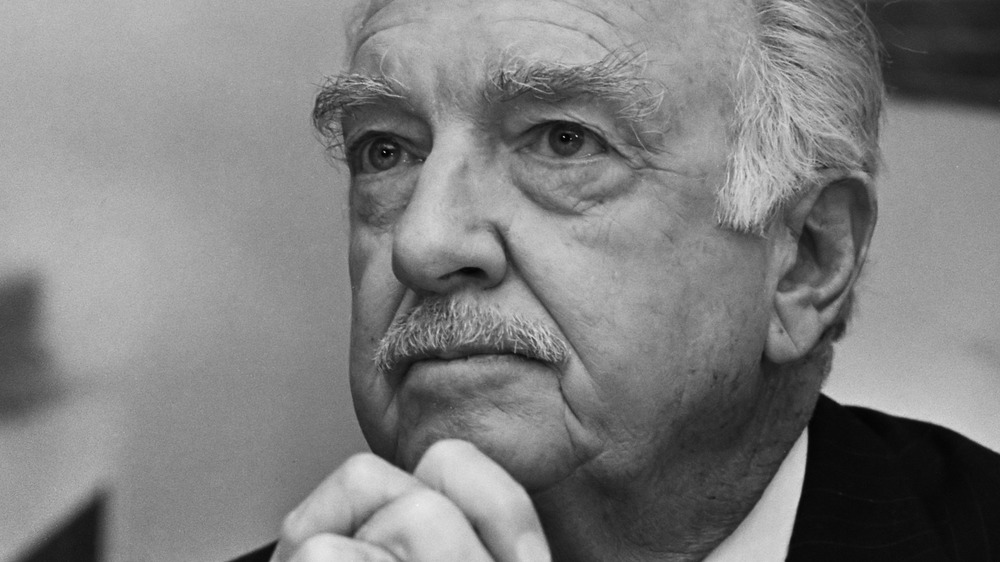

However, she never lost her fighting spirit. First-term "freshman" House members are traditionally expected to stay quiet, follow orders, and take the assignments they're given. But Chisholm continued to defy expectations. Chisholm used her first floor speech, in March 1969, to criticize the Vietnam War and said she would vote against any bills funding the military. When she was assigned to the Agriculture Committee, she rebelled, arguing that it wasn't relevant to her district. "Apparently all they know here in Washington about Brooklyn is that a tree grew there," she said, according to the New York Times.

Chisholm bypassed Congressman Wilbur Daigh Mills, who was responsible for assigning Democratic committee appointments, and took her case to House Speaker John W. McCormack. When he ignored her complaints, she made a speech to the Democratic caucus on the House floor, while also doing interviews with the press. Her persistence paid off — she was reassigned to the Veterans' Affairs Committee, which was slightly more relevant. Starting in her second term, she served on the Education and Labor Committee, which had always been her first choice given her background in education.

In 1971, during her second term, Chisholm co-founded the National Women's Political Caucus with the aim of increasing women's political involvement.

Shirley Chisholm was the first Black woman to run for president on a major party's ticket

Women have been running for president since before they could vote. A white women's suffrage campaigner, Victoria Woodhull, was nominated by the Equal Rights Party exactly 100 years before Shirley Chisholm ran, in 1872. And in 1968, Charlene Mitchell, became the first Black woman to run for president, as a member of the Communist Party.

However, Chisholm was, as she put it, the first Black person to seriously run for president for a major party and the first woman to run for the Democratic nomination. She announced her candidacy in January 1972, declaring herself as the candidate of the marginalized, especially poor people, women, Black people, and young people.

Chisholm knew that she probably wasn't going to win, but according to the Washington Post, she aimed to get enough votes that she and the marginalized people she hoped to represent would have some influence at the Democratic National Convention (DNC). For example, she wanted to force the candidate to name a Black vice president and a Native American secretary of the interior (which is still being pushed for today). But above all, she wanted to prove that Black people, women, and particularly Black women have as much right to run for president as white men. "Because a white male has always been the person who has entered into the White House, I don't see why it is that I should step back," Chisholm maintained.

Shirley Chisholm was patronized by the media throughout her campaign

From the moment Shirley Chisholm announced her campaign for president, she was bombarded with sexist commentary, racism, ridicule, and a basic lack of respect.

CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite joked that instead of throwing her hat into the ring, she threw a bonnet. She was excluded from appearing in a televised debate alongside rival candidates George McGovern and Hubert Humphrey — until she successfully filed a complaint with the Federal Communications Commission. According to the Washington Post, a President Richard Nixon-fixer even wrote a memo on stationery stolen from Humphrey's campaign, claiming that Chisholm had been hospitalized in a Virginia mental asylum.

During the campaign, Chisholm received at least three death threats. Her husband, Conrad Chisholm, became her unofficial bodyguard. It wasn't until rival Democratic candidate George Wallace (Governor of Alabama and notorious racist) survived an assassination attempt that Nixon assigned all the candidates Secret Service protection.

Plenty of white people openly refused to vote for a Black candidate. But Chisholm felt that her gender was used against her more than her race. In 1982, she told the Associated Press, "When I ran for the Congress, when I ran for president, I met more discrimination as a woman than for being black." That extended to some Black men too. According to the LA Times, Chisholm once said, "Not many black people can really believe that a black person, who also happens to be a woman, can become president of this country."

Shirley Chisholm's coalition didn't work out

Shirley Chisholm inspired many people around the country to volunteer for her underfunded campaign. They managed to get her name on the ballot in 12 states. She also received an endorsement from the Black Panther Party — and accepted it, despite backlash.

However, Chisholm struggled to convince many Black men and white feminists to commit to her when it mattered at the DNC. She delivered emotional speeches to the Women's Caucus and the Black Caucus, promising that if they united behind her they could influence the party's program. But according to the LA Times, only two other members of the Congressional Black Caucus (which she had co-founded in 1971) endorsed her — and even they dropped out at the DNC. Some felt she should have asked them for permission before running for president.

The National Organization of Women (NOW), which Chisholm was an early member of, refused to officially endorse her. White feminists like Gloria Steinem and Bella Abzug ultimately supported George McGovern, who was more progressive than his fellow frontrunner Hubert Humphrey. (McGovern later betrayed the feminists' faith by refusing to put a reproductive rights plank up for a floor vote at the last minute.)

Chisholm finally collected 151 delegates, which was respectable given her underfunded grassroots campaign but nowhere near enough. Yet she maintained, "My greatest achievement... is that I had the audacity and the nerve to make a bid for the presidency of the United States of America."

Shirley Chisholm risked her political career for an unlikely alliance

On May 15, 1972, Democratic presidential primary candidate George Wallace was shot and paralyzed while giving a speech in Laurel, Maryland. Then-governor of Alabama, Wallace was infamous for being an ardent segregationist and racist. Which was why many of Shirley Chisholm's supporters were appalled when she temporarily suspended her campaign to visit him in the hospital.

Wallace was apparently shocked too, especially when she told him, "I wouldn't want what happened to you to happen to anyone." Wallace's daughter, Peggy Wallace Kennedy, told the Washington Post, "Daddy was overwhelmed by... her willingness to face the potential negative consequences of her political career because of him."

Despite the backlash from her supporters, Chisholm maintained that she had done the right thing. One campaign worker, Barbara Lee, now a California congresswoman, recalled to the Post that Chisholm told her, "I may be able to teach him something, to help him regain his humanity, to maybe make him open his eyes to make him see something that he has not seen."

It seems she did. Wallace renounced his former beliefs, publicly asked Black leaders and communities for forgiveness, and appointed a record number of African Americans to state positions. Kennedy credited Chisholm with starting this change, saying she "planted a seed of new beginnings in my father's heart." Wallace also repaid Chisholm directly, helping her gather Southern votes for her 1974 bill to extend minimum wage laws to domestic workers, many of whom were Black.

Shirley Chisholm served in Congress for seven terms

Shirley Chisholm championed the marginalized throughout her seven terms in Congress. Before her presidential run, she and Bella Abzug introduced a bill that would have funded high quality childcare for all families. It passed the House but was vetoed by President Richard Nixon.

Chisholm later sponsored a bill extending and amending the school lunch program and introduced an amendment that made it possible for 5 million more children to access free lunches, according to the New York Times. When President Gerald Ford tried to veto the bill, Chisholm convinced her colleagues to override him. She also championed a guaranteed minimum annual income for families, a Farmworkers Bill of Rights, a bill to amend asylum procedures, and a bill that would have returned areas of the Black Hills National Forest to the Sioux Nation for 10 years.

In 1977, Chisholm co-founded the Congressional Women's Caucus and became the Secretary of the House Democratic Caucus. She also gave up her hard-won seat on the Education and Labor Committee to become the first Black woman and second woman ever to sit on the powerful Rules Committee. In 1978, she demonstrated her independent spirit when she became the lone Democratic holdout in the Committee on the Natural Gas Regulation bill, arguing that it would disproportionately impact the poor. Throughout her career, she refused to automatically endorse candidates or colleagues just because they were female, Black or a Democrat, and she made deals with Republicans to get what she wanted.

Shirley Chisholm retired from politics in 1982

In 1982, Shirley Chisholm announced that she wouldn't seek re-election. Her decision was partly based on the general political shift to the right, which she felt impacted her ability to pass the progressive legislation she wanted. And partly it came down to personal reasons.

Chisholm's second husband, Arthur Hardwick, was badly injured in a motorcycle accident in 1979. Nearly losing him made Chisholm realize that she'd given so much of herself to her political career that she'd neglected her personal life. "I had no time for privacy, no time for my husband, no time to play my beautiful grand piano. After he recovered, I decided to make some changes in my life," she told the New York Times.

She told the Washington Post that she didn't decide to leave Congress immediately after Hardwick's accident, and that he encouraged her to go back to work. But the job she had once enjoyed began to wear on her, especially as she felt that she was no longer able to be as effective as she used to be.

Chisholm's retirement was greeted with mixed emotions. The independent streak that had seen her occasionally break with the Democratic party line and expectations of many in the Black political community had made her enemies. But she also received thousands of letters and visits from people who were devastated that she was leaving, and she felt some guilt — but true to form, she never wavered on her decision.

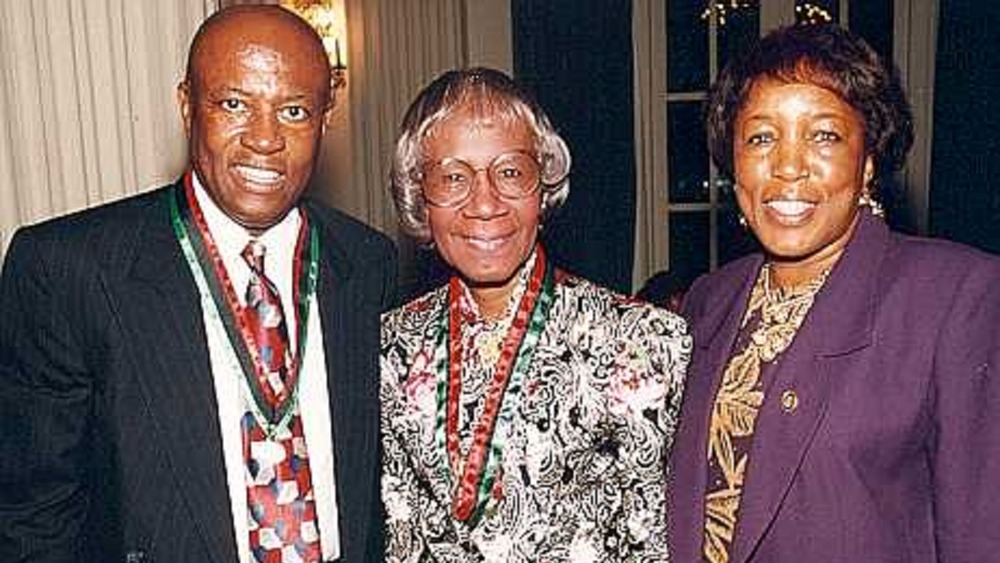

Shirley Chisholm is finally getting her due

Shirley Chisholm didn't spend all her retirement playing piano. From 1983 to 1987, she taught politics and sociology at Mount Holyoke College. In 1984, she co-founded the National Congress of Black Women and campaigned for Jesse Jackson's presidential bid — even though he had been one of her main detractors during her own campaign.

Chisholm died, aged 80, on Jan. 1, 2005, after a series of strokes, the New York Times reported. Today, more people are acknowledging Chisholm's legacy and her impact on American politics. In 2015, President Barack Obama awarded her the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In 2019, the largest state park in New York City, the Shirley Chisholm State Park, opened in her former district and childhood home, Brooklyn, in her honor. She was played by Uzo Aduba in FX's miniseries on the Equal Rights Amendment, Mrs. America, in 2020. And Danai Gurira is set to play her in an upcoming movie following her presidential bid, The Fighting Shirley Chisholm.

As someone who became a "first" many times in her life, Chisholm knew that she'd made history. But in an interview shortly before her death, she said, "I want history to remember me not that I was the first black woman to be elected to the Congress, not as the first black woman to have made a bid for the presidency of the United States, but as a black woman who lived in the 20th century and who dared to be herself."