Cold War Escapes That Were Absolutely Unbelievable

Few commentators would describe the Cold War as a fun experience overall, but most would agree that what fun there was to be had was in the West. The West famously had rock 'n' roll, blue jeans, and Coca-Cola; the East had grey concrete architecture, intense internal surveillance, and the ever-present threat of punishment — including torture and murder — for not being enough of a good socialist worker. (Plus, at least in the Soviet Union, instead of Coca-Cola they had soda vending machines, which dispensed the drinks directly into one or two glasses that everyone shared.)

Plenty of people locked behind the Iron Curtain wanted to take their chances in the "decadent" West, but it wasn't as easy as asking nicely. Instead, enterprising Eastern Bloc citizens hoping to change their futures improvised vehicles, dug tunnels, hollowed out cargo, and otherwise found ways to slip across the border into West Germany, Austria, Denmark, and, in one especially bold and glamorous escape, Australia. Their ingenuity and daring made their stories of escape thrilling reading — and perhaps an inspiration to others who find themselves on the unhappier side of a closed border.

One family used a homemade tank

Vaclav Uhlik Sr., had been sent to concentration camps twice during World War II, so he was understandably well and truly done with totalitarianism. Unfortunately, it wasn't done with him: a coup in 1948 brought a Communist government to power in Uhlik's native Czechoslovakia. An auto mechanic who owned a garage before the coup, Uhlik had the idea to soup up an old German armored vehicle he used to haul logs and punch through the border fence.

It took Uhlik five years to reinforce the vehicle and construct his plan. He would go out drinking with the guys who manned and maintained the border fence, nursing his drinks while they got drunk enough to let slip details about where the fence was weakest — and where the land mines were. Uhlik chose a marshy spot over which treads could pass more easily than common wheels, reinforced his homemade tank, and dressed it up to look like it belonged to the Czech military.

And then, on July 25, 1953, Uhlik loaded his tank with his wife, their two children, a family friend, a friend of that friend, and two other people who really wanted out of Czechoslovakia: an alleged "enemy of the people" and a woman with an American husband. With Uhlik at the wheel, the tank crunched through the barbed wire at the chosen spot, and the passengers made it unharmed into West Germany.

A German soldier stole a tank

The dynamics of the division of Germany meant that most of Berlin existed as an island of West Germany surrounded by the East. Literally millions of people had scampered into West Berlin since the country's division, including so many professionals that the brain drain was sapping the eastern economy. So, in 1961, East Germany built the notorious Berlin Wall, sealing the city off from any East Germans who wished to live in the other Germany.

One of the men who built the Berlin Wall was unhappy about that, so he stole an armored car and drove through it. One day in April 1963, East German soldier Wolfgang Engels helped himself to a Soviet-made armored personnel carrier and drove it most of the way through the then-cinderblock Berlin Wall. The vehicle got stuck partway through, and when Engels climbed out he got caught in some barbed wire. The East German border guards shot him twice, but under suppressing fire from their West German counterparts, some drinkers at a nearby bar were able to haul the tattered Engels to safety. He recovered and lived to see the Berlin Wall fall in 1989.

Miscellaneous hollowed-out objects

While the Berlin Wall was imposing and dangerous, it was never fully sealed, and regulated traffic passed across the border. So if you could hollow something out and hide in it while someone with legitimate business on the other side drove it across, you could be in business — as long as you didn't sneeze.

Cars could be outfitted with secret compartments, with some people even emptying the stuffing out of seats and climbing in, closing the fabric behind them. One guy hid his (apparently small) girlfriend between two hollowed-out surfboards, which were attached to each other and strapped to the roof of his car. The exteriors of portable speakers and a radio, both big pieces of equipment in those days, could be emptied and refilled with refugees. And in perhaps the most amusing case, an artificial cow intended as part of an advertising display made the crossing several times with its belly full of East Germans, who had paid handsomely for the privilege of riding to freedom within a Trojan cow.

An early airplane hijacking

There is, surprisingly, some debate over which incident is the earliest known airplane hijacking, with various incidents in the late 1940s and early 1950s vying for the dubious honor. So while Hungarian bricklayer Frank Iszak's plan to commandeer an airplane in Hungary and fly it to the West might not be the very first, it's certainly among the few incidents where it's easy to root for the hijackers.

Iszak, his wife Anais, and a group of friends that included a former fighter pilot boarded a small commercial flight in Budapest on July 13, 1956, which was headed for Szombathely in Hungary's west. They overpowered the flight crew and an unexpected secret policeman on board; between the brawl and the shaking of the plane, everyone on board was injured. The plane didn't have much extra fuel, either, as it was supposed to be a short trip across Hungary, so it was a harrowing trip through the cloudy Alps with iffy navigation and an unsecured door that had been damaged in the fight. When they ran low on fuel, they brought the plane down out of the clouds, not knowing where they were... only to find themselves right above an airstrip at a NATO airbase in West Germany.

Sheer pizzazz

Germans couldn't move freely between the halves of Berlin, but foreigners could, which is how Austrian citizen and West Berlin resident Heinz Meixner met East German Margarete Thurau at a dance. They hoped to marry, but East German officials told Thurau she should bring her fiancé to East Germany rather than go to Austria. Unimpressed with that plan, Meixner came up with a better one.

As he moved across the border, he was able to approximate the height of the barrier that guards would lift to allow cars to pass, and then he rented the smallest, coolest, lowest-to-the-ground car he could find: an Austin Healey Sprite. Meixner had an accomplice agree to hold up west-to-east traffic at the chosen time. Meanwhile, Meixner himself uninstalled the rental car's windshield and put Thurau's mother in the trunk, behind a layer of bricks to shield her from potential gunfire should the East German guards try to stop them with force. With the conveniently small-boned Thurau crouched in the back seat, the group approached the crossing from the east.

When Meixner got to the head of the line, he floored it. The security bar passed over the Sprite with a couple of inches to spare, and Meixner and the ladies whizzed into West Berlin with panache.

A tunnel under the Berlin Wall

You couldn't go through the Berlin Wall, and it was hard but not impossible to go over it; to a certain type of engineering mind, that left going under it as the remaining option. Several successful tunnels were built under the wall to ferry out escapees. The work was difficult: tiring and claustrophobic, yes, but it also came with the risk of being discovered by the East Germans, who were themselves digging tunnels to try to intercept these rescue attempts. Furthermore, secretly disposing of the resulting soil and debris was also a big job.

The most famous tunnel became known as Tunnel 57, as 57 people were able to use it to exit East Germany. The tunnel crew had rented an abandoned bakery right next to the wall, and its basement was one end of the tunnel. The other end was ultimately an outhouse-turned-shed in the courtyard of an apartment building in the East. During the nights of October 3 and 4, 1964, 57 people with the code word "Tokyo" were allowed into the courtyard and able to pass through the tunnel before the group was betrayed to the East German authorities. The police arrived and opened fire, but they only killed one of their own; all the escapees made it to the West.

A little homemade submarine

Bernd Böttger was born with a mechanical mind, which brought him to the attention of East German authorities early in life. As a teenager, Böttger built a homemade rocket, which landed in the courtyard of the local police station. Though he wasn't directly punished, the Stasi were watching him, later forcing him out of a college engineering program. It seems they were suspicious that he could figure out how to fly over the border.

Böttger instead figured out how to go around it. He built a gasoline-powered underwater engine that could pull him through the sea to the West. When the prototype craft, which he called the Aqua Scooter, was confiscated by authorities after a test run in the Baltic Sea, he redesigned a quieter, more efficient version. Then, on September 8, 1968, Böttger headed back to the Baltic coast. In a wetsuit and bearing an inflatable mattress, which he could inflate and use as a workspace if the Aqua Scooter needed repairs at sea, he entered the water and headed for Denmark.

Böttger narrowly escaped detection by the East German coast guard, staying under the surface and holding his breath until he heard the boat move away. More amusingly, he also nearly ran into a codfish. Finally, after about six hours in the water, Böttger came across a Danish coast guard vessel that pulled him up and deposited him in Lubeck, West Germany, where the handsome young inventor showed off his device to an impressed public.

A hot-air balloon

Albuquerque, New Mexico, has hosted a hot air balloon festival every year for decades. So when Günter Wetzel happened to see a news report about the festival in the late 1970s, he thought that, perhaps, he could make his own balloon to get his wife and friends out of East Germany. After years of work and two failed launches, he did just that.

Without access to information about balloon construction, Wetzel and his fellow would-be balloonists — his wife Petra, their friends Peter and Doris Strelzyk, and the couples' children — had to guess, hope, and experiment, all with clandestinely acquired materials. Strelzyk sewed the balloons on his mother-in-law's old yet reliable sewing machine, trying to maximize efficiency (since they didn't have fabric to waste) and using reinforced stitches. Fortunately, Wetzel's interest in physics and engineering helped them troubleshoot and refine the design.

On September 14, 1979, the third balloon was ready, and just in time: authorities had found the wreckage of a balloon the Strelzyks had experimented with on their own and were suspicious. The group rose into the night sky in the small hours of September 16, but the flight wasn't completely smooth: an anchor hit one of the Strelzyk sons in the head as they lifted off, and the burner scorched a hole in the top of the balloon. Fortunately, the group managed to avoid becoming one of history's deadliest hot air balloon accidents and landed without serious injury. As they had had limited ability to navigate in the balloon, there was some suspense as to whether they'd made it, but they had successfully crossed into Bavaria, one of the states of West Germany.

A swim to Australia

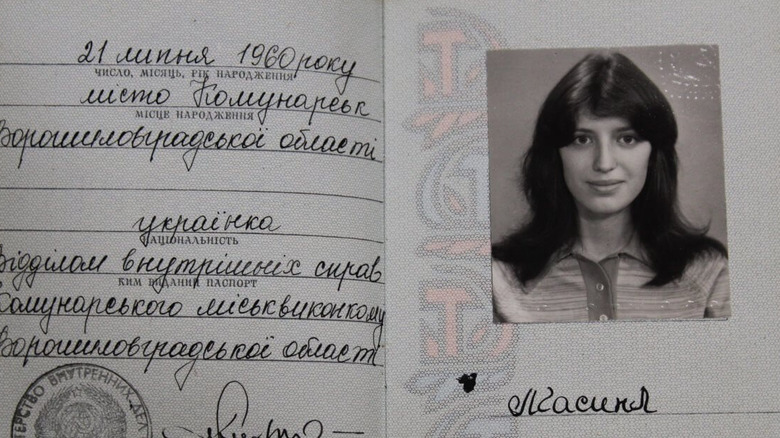

Liliana Gasinskaya had an ulterior motive when she applied to work on a Soviet cruise ship, which serviced a route between Australia and the United Kingdom. On January 15, 1979, as the ship approached Australia, she put on a red bikini, wriggled through a porthole, and dove into the sea. It was summer in the Southern Hemisphere, fortunately, and Gasinskaya came ashore in Sydney harbor after about 40 minutes in the water. Gasinskaya became known as "Red Bikini Girl," joining '70s icon Farrah Fawcett as a heartbreaker in an eyecatchingly vivid swimsuit.

A pretty young woman with an amazing story, Gasinskaya quickly made headlines — and controversy. She was granted asylum in Australia, but the country had only in 1975 dropped its "White Australia" policy of generally only allowing Caucasian immigrants, and now here was an attractive white woman appearing to receive special treatment by swimming herself to the front of the line. Gasinskaya's behavior added to the pearl-clutching: she appeared nude in an Australian edition of "Penthouse" and later complicated her legal status with an apparent attempt to travel on an old Soviet passport. Regardless of these ruckuses, she was allowed to stay in Australia and marry, before dropping out of the public eye in the late 1980s.

A homemade airplane

If you really, really believe in yourself, you can build an airplane. In the United States, you can actually purchase a kit to do so, but in communist Czechoslovakia, it was much harder. However, Ivo Zdarsky made it happen.

With all respect to Zdarsky, "airplane" is perhaps generous: what he built was a motorized tricycle with wings. It was, however, sufficient to get him off Czechoslovakian soil, which is what he wanted. Early on the morning of August 4, 1984, Zdarsky lifted off from a field in Slovakia in his air-trike, with Vienna visible in the distance. Guided by the Big Dipper and a simple compass, Zdarsky achieved sufficient altitude to cross the Morava River that marked the border without incident.

Once over Vienna, the airborne adventurer looped over the city a bit, enjoying his freedom and taking in views of the Danube and the city's wide and lovely avenues, before flustering air-traffic controllers by landing at Vienna International Airport. Zdarsky later moved to the United States, where he built another air-trike to explore the California desert, before finally graduating to aircraft other people had built.

A zipline into Austria

People couldn't cross the border between Czechoslovakia and Austria freely, but electricity could. High-tension electrical wires connected a power plant in southern Czechoslovakia to users in Austria, and so friends Daniel Pohl and Robert Ospald decided they'd hitch a ride, using homemade seats to construct the wires into ziplines that would, if all went well, whizz them right into Austria.

Pohl and Ospald hid out in a cornfield near the border for two days, waiting for a thunderstorm that would prevent border guards from hearing any telltale clattering. The storm came on the very early morning of July 19, 1986. They climbed up one of the pylons, attached their seats to the topmost wires (which did not carry electricity), and wished each other luck. Momentum wasn't enough to carry them all the way from pylon to pylon, so they had to pull themselves along the wire, but after over four hours of dangling and scooting, they made it into Austria. Among the refreshments the Austrians gave the weary asylum-seekers was that most symbolic Cold War drink: Coca-Cola.

The Pan-European Picnic

In 1989, it was clear that Communist governments in Eastern Europe were teetering, but none had yet toppled. As a celebration of the apparent thaw, organizers in Sopron, Hungary, planned a picnic to take place at the border between Austria and Hungary, old roommates of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that had been divided by the Iron Curtain after World War II. Austrians who wanted to come hang out were invited across for the event.

East Germans were allowed to travel freely to their Warsaw Pact ally Hungary, but not to Austria. News of the picnic and the presumably relaxed border security that would accompany it circulated, and a surprisingly large number of East Germans just happened to show up on August 19, 1989, ready to enjoy food and friendship. Unknown to Hungarian authorities, they intended to do so in Austria.

People passed around pliers to take down the parts of the fence that had not been opened, and soon East Germans were streaming across the border, their ranks swelling as people realized the Hungarians were unwilling to use force against them. Hundreds of people made it across to Austria during the picnic. In September, the border was opened; in November, the Berlin Wall fell; and in 2007, Hungary joined the European Union's single-visa travel zone, meaning that for many crossers the old line between the countries is only a formality.