The History Of Sewage Is Stinkin' Impressive

It's an inescapable fact of life: Everyone produces waste. After all, the food and drink you consume have to go somewhere after your body's done with them. Urinating and defecating are such standard parts of life that we hardly ever think about where our waste products end up after we go about our, er, business. But in many places worldwide, that's where sewer systems come in: a practically invisible mechanism of pipes, drains, and treatment plants that carry our waste away, protect our water supply from contamination, and prevent the spread of dangerous diseases like cholera and typhoid. And it might come as a surprise to many that the idea of constructing this critical waste management infrastructure (or at least, the modern version of it) isn't even two centuries old.

That's not to say, of course, that ancient civilizations didn't have their own ways of handling their putrid pee and poo problems. Over the years, archaeological evidence has shown that prior to the existence of today's sewer systems, ancient civilizations in different parts of the world built communal and private toilets, as well as proto-sewers that carried human waste to nearby bodies of water.

With the steady march of technology, though, humanity has come a long way toward improving what is perhaps the most overlooked defense system for human health — even though, to this day, not everyone on the planet is fortunate enough to benefit from it.

Solving the disposal of human waste began with the rise of ancient cities

Chances are that you live in a household where you can simply go into the bathroom, sit on the toilet, and take the time to read a newspaper or ponder the mysteries of life until you're done and it's time to press the flusher. But pre-sewer urban life wasn't as convenient. This isn't entirely surprising, though, considering that the issue of human waste disposal didn't really exist before towns and settlements were a thing. As far back as 10,000 years ago, the global human population wasn't big or clustered enough to make using nature to absorb our byproducts problematic.

However, as populations became concentrated in certain areas, the need to deal with literal crap quickly became apparent, and ancient communities handled this problem in effective yet limited ways. In the Mesopotamian city of Babylon, around 4000 B.C., the earliest known means of sanitation was a simple cesspit: a deep enough hole to collect and hold fecal matter, which was transported from homes via bucketfuls of water traveling through clay pipes that served as conduits. The ancient Greeks, particularly the Minoans from the island of Crete, were said to have used similar systems.

In Scotland, houses at the smallish Neolithic settlement of Skara Brae — occupied between 3200 to 2500 B.C. — had drains built into their wall that strongly suggested they functioned as indoor latrines. And around 3000 B.C., Mohenjo-Daro, located in present-day Pakistan, had buildings with "true" latrines connected to a sophisticated system of drains.

Ancient civilizations didn't waste wastewater

From what we know about the ancient world, people treated dirty water as a resource, not just refuse: Rather than wasting wastewater, they folded it into urban life way before the idea of actively recycling water became a rallying cry to save the environment.

Bronze Age farmers in early river civilizations, such as those in Egypt, the Indus Valley, and Mesopotamia, channeled household wastewater to aquaculture systems and fields, presumably using the moisture and nutrients in the water to keep crops alive during dry seasons. In South Asia, this practical mindset is evident in archaeological finds; cities such as Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa laid out brick-lined, covered drains beneath streets, with bathrooms and latrines in many houses discharging into a municipal network fitted with access covers and sumps. Essentially, the urban plumbing that kept filth off their streets also made it possible to divert sewage to the margins of towns for irrigation, a system observed in other sites of Indus Valley civilizations.

Between A.D. 250 and 600, Mayan engineers in the city of Palenque, Mexico, devised a pressurized aqueduct by narrowing an underground conduit. Archaeologists speculate that, besides possibly powering a fountain, the generated pressure could have also lifted flows onto nearby platforms for wastewater disposal or reuse. This water system is said to be the earliest known example of engineered water pressure in the New World.

Rome had a famed sewer that helped it become a powerhouse

Experts recognize the role played by the Cloaca Maxima, Rome's "sacred sewer" or "Great Sewer," in enabling the ancient civilization to rise and prosper the way it did. A state-organized sewer constructed in the 6th century B.C. under the orders of King Tarquinius Priscus, the Cloaca Maxima served as a monumental drainage canal from the center of Rome to the Tiber River. Later on, it was roofed with stone vaults and tied into a growing network of conduits that served public baths and multi-seat latrines, ultimately reaching a staggering 1,600 meters in length. This was less of a testament to the Romans' understanding of physics (which arguably wasn't perfect) and more of a grand solution to the problem of people stinking up the streets with their excreta.

The sewer unlocked central building sites for markets, temples, courts, and roads, concentrating people and commerce where power could be exercised most effectively. Its effect was equal parts strategic and sanitary: by shunting standing water and filth into a controlled outfall, the system reduced the stagnant pools that bred disease-carrying mosquitoes and the runoffs that fouled the streets.

The Cloaca Maxima also carried symbolic weight: Romans treated it as a quasi-sacred civic asset, a fact evident in the public resources devoted to its inspection, repair, and extension over the years. Unsurprisingly, it became a fixture in their literature, artworks, and currency, with historians and artists chronicling its significance in Roman society.

Medieval Europe eventually reverted to open ditches and cesspits

After Rome's fall, its pioneering wastewater management systems were seemingly washed away from society as well. In the Middle Ages, many European towns apparently handled waste with bare-bones methods: open gutters along lanes, backyard cesspits, or just straight-up chucking feces into the streets. Excavations in medieval neighborhoods show thick bands of household refuse and latrine sludge, with pits cut alarmingly close to wells. Permeable soils and high water tables let liquids creep sideways and downward, tainting sources meant for drinking. Archaeologists tracing cesspit sequences in densely built quarters have also documented repeated cycles of digging, lining, use, overflow, and abandonment over hundreds of years.

Enter the night soil men, Victorian England's cesspit-cleaning professionals, who became essential workers as the industrial revolution swelled city populations in the 1800s. Households hired pit-emptiers only when cesspools overflowed or threatened collapse, and the work was irregular and incomplete: walls leaked, bottoms silted, and fresh waste quickly refilled the voids. Written accounts of "night soil" collection in other parts of the world, including America, illustrate why such systems never provided real containment: even where carts removed solid human waste, seepage, spills, and illicit dumping guaranteed that much of the disgusting load still reached streets and waterways.

Still, the public health consequences were predictable for crowded towns without proper wastewater management: frequent bouts of gastrointestinal disease, periodic mass mortality from epidemic infections, and a truly terrible stench that officials tried (and largely failed) to mitigate with fines and edicts. Sadly, this became the norm for Victorian-era hygiene for quite some time.

London's Great Stink of 1858

If you've ever heard someone say that cholera is responsible for modern sewer systems, here's why. In London, during the searing summer of 1858, heat concentrated the River Thames' burden of human waste into a nauseating miasma that Londoners christened the Great Stink. Along with this olfactory assault came a sharp rise in cholera and typhoid cases. But the truth behind the Great Stink of London is that decades of rapid population growth, alongside worsening air pollution and poor wastewater management, had already brought the city dangerously close to drowning in the stench of human filth; the introduction of flushing toilets in households — and the increased water pressure that came with them — pushed it past the limit.

In response to the crisis, officials entertained civil engineer Joseph Bazalgette's proposal: long interceptor sewers on each bank to capture the city's myriad local drains and carry the combined flow away from central intake points. Massive underground brick tunnels, pumping stations at Abbey Mills and Crossness, and new riverside embankments formed an integrated system that moved millions of liters of household wastewater daily toward outfalls downstream, where the tides could disperse it until treatment works were added.

While it would take almost two decades to complete, the project's effects were quickly felt. After the completion of the core network, the horrific smell faded away from the Thames. Additionally, cholera all but vanished from London, with a final localized outbreak in 1866 that pretty much ended the U.K.'s part in the messed-up history of cholera.

A problem with Bazalgette's sewer system

Unfortunately, while Joseph Bazalgette's sewerage innovation helped solve London's central cholera crisis, it didn't solve the underlying problem of actually disposing of waste. The new brick mains gathered sewage and, with help from the grand pumping stations, sent it east to be dumped on the outgoing tide — moving all the stench and contamination to the Thames estuary, much to the distress and discomfort of the people living near and along it.

The most severe consequences of this system became apparent in September 1878, when the pleasure steamer SS Princess Alice sank near the outfalls at Gallions Reach, right after millions of gallons of effluent had been discharged at that location. The approximately 650 passengers and crew floundered and drowned in the sewage-laden waters; the catastrophe served as a demonstration of the risks of pouring raw waste into a working river used by downstream communities.

Public pressure and official investigations then pushed London toward establishing a working scheme of wastewater treatment. Large settling and chemical-precipitation tanks were added near the main pumping stations so solids could be separated rather than flushed straight into the Thames. From 1887, the sludge was loaded onto purpose-built vessels — nicknamed "Bovril boats" due to the sludge's resemblance to beef extract – and hauled to sea for disposal, while the clarified liquid fraction still flowed to the river. This arrangement gradually evolved into more modern treatment works, and although the practice of sludge boat dumping supposedly continued until the final decade of the 20th century, U.K. laws eventually banned this form of waste disposal.

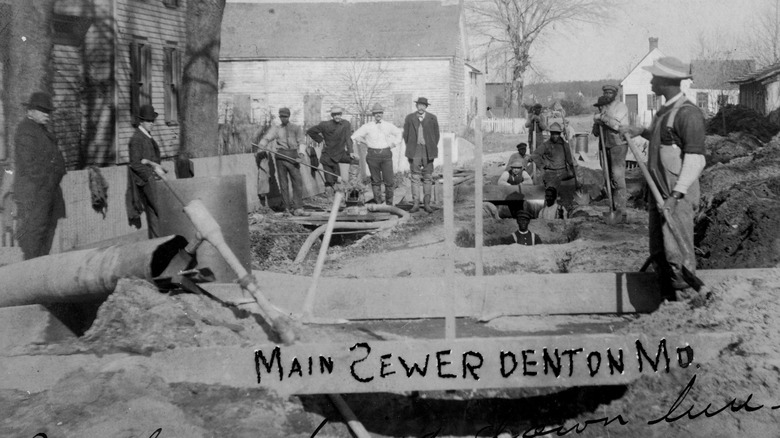

Milestones in sewage system development in the United States

On the other side of the 19th-century globe, many American towns employed a similar "night soil" system of dealing with human waste. Night soil men ladled the contents into barrels and carted them through the streets via their "rude carts." Loads that were not spread on fields were dumped at piers or straight into rivers, where waste settled into harbor slips and was periodically dredged back out just so boats could actually use said harbors.

One of the most significant sewage milestones in the United States took place in Chicago, Illinois, clustered around the city's fight with cholera (and, well, trying not to be waist-deep in waste). After a deadly cholera outbreak in 1854, engineers launched a city-reshaping plan to literally hoist buildings and roads, then lay sewer pipes in the newly created space underneath to carry the flow to the Chicago River. At the time, this may have seemed like an adequate solution; however, all that untreated wastewater eventually threatened to contaminate the population's drinking supply. Additionally, Chicago's drifting filth became the problem of other cities downstream, which necessitated the addition of wastewater treatment as a step in the process.

In 1890, the first sewage treatment plant to use chemical precipitation (a process that settles and removes solids from a solution) opened in Worcester, Massachusetts. By the early 20th century, cities were layering treatment onto their conveyance systems, resulting in dramatic declines in typhoid and other waterborne illnesses, and establishing the template for modern wastewater management across the United States.

Activated sludge technology was a revolutionary biological wastewater treatment

An important development in sewage treatment — one that is still regarded as a fundamental consideration for wastewater plant design in modern times — is the implementation of the activated sludge approach. Proposed by U.K.-based engineers Edward Ardern and W.T. Lockett in 1913, this biological process involves keeping aerated sewage in contact with a dense, reusable microbial floc (a clumped mass of microbes suspended in a liquid), after which the settled solid contaminants can be recycled to help treat the next batch of sewage. The approach was published in 1914, and cut sewage treatment times from days to hours by accelerating the oxidation of organic material. Additionally, early trials showed it could be operated continuously with a return-sludge loop.

The timing was just right, too, as cities in Europe and the United States were just beginning to establish sewage systems as more effective alternatives to cesspits and "night soil" men, and U.K. utilities rapidly adopted the method. Within a few years, plants in North America and other parts of Europe followed, establishing activated sludge as the core of secondary treatment, rather than simply sending untreated human waste to a river. In succeeding years, researchers continued to further refine both the procedures and the mechanisms involved in activated sludge treatment, ensuring that it could remain scalable and viable, more than a century after its conception.

The 20th century saw further development of sewer systems in U.S. cities

In the United States, the construction of municipal sewer systems was in full swing near the turn of the 20th century. Chicago had already laid down more than 500 miles of sewers, Philadelphia had constructed an almost 400-mile stretch, and New York and Brooklyn managed to build a combined 844 miles. However, the building boom that took place after World War II meant that newly built homes for returning soldiers were unable to connect to these sewers. Instead, to keep up with the breakneck pace of construction, these homes came with septic tanks or wells. While this kind of setup works adequately for rural communities, the limited spaces that these homes were built on introduced the risk of groundwater contamination, not to mention that upgrading septic tanks entailed hefty costs.

Today, there are three basic types of collection systems used for the removal of wastewater and stormwater in urban homes in the United States: sanitary collection systems that carry wastewater to treatment plants; stormwater collection systems, which are mainly a flood prevention measure, and combined wastewater and stormwater collection systems, which are more expensive to maintain and may even pose environmental risks. In the case of the latter, despite the drawbacks, combined sewer systems serve some 40 million people in 32 states.

Sewer systems have driven disease rates down, but hundreds of millions still lack access

The global adoption of modern sewer systems didn't just make it easier to flush away human waste; some of the world's most dangerous infectious diseases were sent down the drain, too.

A 2020 study published in Neglected Tropical Diseases examined data on typhoid transmission in 16 U.S. cities from 1889 to 1931, revealing that every additional dollar per person invested in water and sewer infrastructure was linked to sizable declines in typhoid transmission. Other studies have found that in Germany, the decline in overall death rates between 1877 and 1913 can be directly attributed to improvements in both water supply and sewerage, and the mortality rates in Paris sank in the same period, also thanks to homes and businesses being connected to modern sewers.

Yet, the global picture today still shows significant gaps. One and a half billion people across the world still have no access to private toilets or latrines, and over 400 million people have no other option than to defecate straight into street gutters or bodies of water. Consequently, a large fraction of household wastewater is still discharged without safe treatment, and poor sanitation is linked to the transmission of cholera, typhoid, and other infectious diseases.

Now that you've become well acquainted with the history of sewer systems, you may want to read up on the untold history of toilets next.