Cholera Is Responsible For Modern Sewer Systems. Here's Why

According to the World Health Organization, between 1.3 and 4 million cases of cholera are reported around the world every year and are responsible for up to an estimated 143,000 deaths. As cholera tends to spread through infected water, access to clean drinking supplies and improved sanitation can work wonders when it comes to keeping it at bay.

In fact, the deadly disease's influence was a huge contributing factor to the creation of today's sewage systems. It's all thanks to the absolutely foul state of London at the time of a notorious cholera outbreak there.

The National Health Service reports that cholera isn't found in the United Kingdom today. It certainly has been in centuries past, though, and was a returning scourge throughout the 1800s. At the beginning of the 19th century, reports the Science Museum, the city had become something of a terrible disease outbreak waiting to happen. The largest city in the world (industrialization had seen the population of London increase at an incredible rate) was not as glamorous as newcomers may have hoped, and those who weren't super-rich tended to be crowded together in grim and dirty slums.

Bazalgette's sewers bring better health

The streets themselves were no better, with waste from animals and humans either dumped or flowing freely. Science Museum reports that deadly diseases like typhoid also struck London, but it was the cholera outbreak that began in 1831 that really marked the start of positive change. Lawyer Edwin Chadwick became the first director of the brand-new Board of Health, after publishing his "The Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population" (1842).

The Health Foundation explains that this report showed the links between squalid conditions and poor health. Chadwick's main takeaway was that social reform and sanitary reform were crucial. Refuse should be cleared away from the streets, Chadwick argued, workers should have access to clean water and the sewers needed improving.

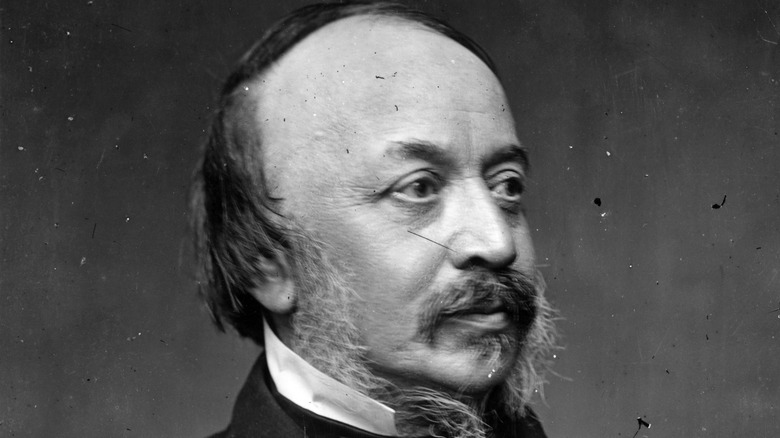

It wasn't until 1865 that London's new sewer system was completed. Per Science Museum, the work was undertaken by Joseph Bazalgette, Chief Engineer of London's Metropolitan Board of Works. Bazalgette's system saw sewage carried from smaller sewers to large, connected ones, which carried the poopy bounty to the end of the River Thames and the ocean rather than letting it surge down the river (the stench of which finally caused the government to take action).

This system was wide enough to accommodate London's booming population and was a great success. Cholera returned to the city only once more, the next year, to a part of London that didn't have access to the new sewers yet. Much of the system is still in use.