The World's Most Sought-After Lost Treasures

Lost treasure sounds like it belongs only on a film set where actors dressed as pirates fight over the glittering stuff. But, give yourself a bit of time to dig into the historical record, and you'll find that there are all sorts of tales concerning treasure that's been hidden or forgotten across the world. Some really do follow the near-cliche of pirates — or at least people who certainly act very piratical — burying their stolen booty on a deserted island somewhere. Other lost valuables came to be missing after all manner of misfortune and accident, be it war, conquest, or even a daring heist or two.

Just what sort of treasure are we talking about, anyway? Yes, some examples do contain old-school chests full of gold coins, jewels, ingots, and other riches. But let's expand our definition of treasure a bit, as we wouldn't want to miss out on stories like those of a missing, quasi-legendary Japanese sword or a cache of stolen art taken in a robbery so shocking that we're still puzzling over it decades later (it's not for nothing that it's been deemed the world's biggest art heist). And, perhaps with some serious dedication and more than a bit of luck, someone in the modern day will finally uncover these long-lost treasures.

Where is all that art stolen from the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum?

It sounds too cinematic: a daring heist that leaves a museum bereft of several artworks. But, in the case of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, that really happened in March 1990. Two men approached the museum in the wee hours and, through an intercom system, told the security guard on duty that they were police officers responding to a disturbance call. When the guard let them in, the men restrained both on-duty guards in the museum basement. Over the course of the next 80 minutes, they took 13 artworks off the walls and left the museum; the guards were discovered by actual police responding over five hours later.

At the time the thieves absconded with the art — including major works by Rembrandt, Manet, and Vermeer — the total loss was estimated at over $500 million. Subsequent detective work led police to believe that organized crime networks in Philadelphia helped move the paintings along. Jimmy Marks, a Boston man who had definitive ties to the criminal world, allegedly claimed that he had two of the missing paintings before his sudden death nearly a year after the heist, seemingly due to a mob hit. His connections and criminal record link up with likely suspects, but even so, the paintings remain missing.

Until then, the museum is offering a $10 million reward for information that leads to the artworks' return and displays empty frames in the galleries to mark the missing pieces.

The Amber Room may be beneath the waves

The Amber Room must have been a sight to behold. When it stood in the Catherine Palace near St. Petersburg, Russia, an opulent room paneled in amber and gold installed in 1745, it must have seemed to glow. But there's a twist: visit the Catherine Palace today and you'll see no genuine Amber Room.

That's because, as with some other bizarre unsolved WWII mysteries, the Nazis stole it. Well, they might have said their ancestors helped create the panels, as they were originally intended for the Prussian emperor. However you wish to interpret history, we do know that Nazi propaganda chief Joseph Goebbels determined which foreign-held artworks were supposedly German in origin and ought to be returned to that nation (where they would either be cherished or sold off). In September 1941, Nazi troops entered the Catherine Palace and dismantled the Amber Room in three days. The panels were shipped to Königsberg, displayed for a while, then dismantled again in 1943 to protect them from Allied bombers. They were last seen in 1945.

Some believe that the panels simply melted or were incinerated in the bombing campaigns that wrecked Königsberg, though others think they were packed on the S.S. Karlsruhe, which sank in the Baltic Sea off Poland in April 1945. Divers identified the wreck in 2020 and have raised some crates found inside, but so far they have only contained military gear and no glittering gold or long-lost amber.

Did someone conceal a lost Da Vinci mural?

Today, fewer than 20 paintings are generally agreed to have been made by Leonardo da Vinci. We only know about other artworks through contemporary accounts and copies, and one in particular remains tantalizing centuries after Leonardo's death in 1519. The Battle of Anghiari, a mural commissioned for Florence's Palazzo Vecchio in 1503, was apparently partially begun when Leonardo finished one 16-foot section, but the project fizzled after that. The hall was only fully decorated in the 1560s, when artist Giorgio Vasari took over. But, beyond Leonardo's original studies, have we lost that first mural? Perhaps not.

Some suggest that Vasari actually painted one section of the mural on a false wall that had been put up to protect Leonard's work. It's not entirely outlandish, as Vasari did that very thing with a revamped altarpiece. Engineer Maurizio Seracini managed to take a sample of this supposed original wall back in the 2000s, but his work proved controversial. Though he claimed to have found pigments that lined up with Leonardo's other work, others said that his quest was putting Vasari's art in danger.

Still, Seracini's theory is at least partially backed up by contemporary accounts of people who claimed to see the Battle of Anghiari ... or was it just Leonardo's framed sketch? The subject remains a matter of great debate in the art history world, but it's highly unlikely anyone will order the destruction of Vasari's murals to find out anytime soon.

The crown jewels of Ireland are still missing

Much like their counterparts in other nations, the Irish Crown Jewels were a richly decorated set that included a bejeweled star, a similarly bedecked badge, and five collars. These were linked to the aristocratic Order of St. Patrick rather than a monarch, but, prior to Irish independence, they were overtly connected to Britain. The order's Grand Master — the one who would be sporting all the jewels — was meant to represent that foreign power over Ireland.

When not in use, the jewels were stored in Dublin Castle, where the Office of Arms was tasked with their safekeeping. That was a pretty weighty task, as they were valued at £50,000 by 1907 (inflation means this figure would soar over £5 million today, or more than $7 million USD). Whoever was in charge messed up in summer 1907, when the door to the castle's strongroom was found open. Even worse, the safe that contained the jewels was unlocked and bereft of its treasure.

The mystery of the Irish crown jewels deepened when police found the safe hadn't been forced, hinting at some sort of inside job, though some involved became litigious when their reputations were put at stake. That didn't stop rumors of scandalous parties at the castle — perhaps a reveler had stolen the jewels then — as well as tricky financial situations of some involved, which may have prompted them to make a grab for the treasure. Whatever happened, the jewels remain missing to this day.

The Treasure of Lima is may still be out there

Despite the name, the Treasure of Lima may not be anywhere near the capital of Peru. Back in 1820, Spain was still a dominant force in the Americas, but the Argentine general José de San Martín was making moves to take Lima and continue his campaign of fighting Spain (he'd already helped gain independence for Argentina in 1812 and Chile in 1818). The Spanish Viceroy ordered the riches under his control to be moved out of the capital. Others added their own valuables to the pile, which was handed over to British trade captain William Thompson.

The idea was that Thompson would sail around with a ship full of riches until it was safe to return to Peru, but we wouldn't be talking about lost treasure if that had worked. Thompson and his crew reportedly couldn't resist temptation, so when they were far out at sea, the viceroy's representatives perished and Thompson had the treasure buried. Where, exactly? No one's sure, not least because much of the crew was caught and executed for piracy.

Only Thompson and his first mate were spared when they promised to lead people to the treasure. They waited for the right moment to simply run off into the jungle of Cocos Island, where they had supposedly hidden the Treasure of Lima in what's now Costa Rican territory. No one found them or the loot, perhaps because Cocos Island is tough to access nowadays. Treasure or not, San Martín did take Lima and helped Peru achieve independence in 1821.

Where is the lost Aztec gold?

There's little doubt that the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán represented a massive achievement in culture, engineering, and city planning — until the conquistadors showed up. Though the story that the Aztec people (also known as the Mexica) thought Hernán Cortés was the deity Quetzalcoatl is almost certainly nonsense, Cortés and company did create an almighty mess. Their attempts to conquer weren't exactly well-received and, after an increasingly tense stay in Tenochtitlán, they attempted to leave in 1520 (after committing a massacre and capturing the emperor). With stolen gold in tow, they were attacked on what's now known as La Noche Triste. Many Spanish died, though Cortés survived and the Aztec people were eventually colonized. But what happened to the treasure?

A tantalizing clue came in 1981, when a construction worker in Mexico City, the metropolis built atop Tenochtitlán, uncovered a hefty gold bar. The location was right for the gold dropped into a canal during La Noche Triste. Researchers studied its chemical composition and found that its metal composition matched up with confirmed Aztec gold, but little else has since been recovered.

Maybe the Aztec managed to spirit it out of town. Montezuma II, the emperor who met Cortés and likely died on La Noche Triste, ruled over a sizable territory. Perhaps the Aztec pulled up the sodden treasure and hid it away somewhere in their empire, or further beyond — some even claim they made it as far as the modern-day U.S.

Is the Florentine diamond somewhere still?

Even if you're a minimalist, you'd probably still take the opportunity to wear a really, really big diamond at least once. In the case of the Florentine diamond, however, you'd have to find it first. Many people would like to do just that, in part because the diamond was a staggering 137.27 metric carats. Legend has it that the diamond came from India, passed through the hands of Portuguese traders, and that Charles the Bold was wearing it when he died in a 1477 battle, but that may be little more than historic gossip.

We do know that the huge rock was owned by Ferdinand II, a 17th-century Duke of Tuscany. After a few aristocratic marriages and perhaps an appearance or two in a royal portrait, it ended up with the Hapsburgs and made its way to the Austrian Empire. Its last known owner was Charles I, the former emperor of Austria, who in 1918 sent the diamond and other jewels to his planned exile spot in Switzerland. However, the Florentine diamond disappeared in transit and hasn't been seen since.

Precisely what happened to it is up for quite a lot of speculation. Some suggest that Charles I or his family simply sold the diamond, seeing as they were set to be fairly cash-strapped in comparison to their previous lifestyle. Or it could be that it was secretly given to a presumably very loyal servant for safekeeping in a far-flung location that remains unrevealed.

The Honjō Masamune sword was lost during the U.S. occupation of Japan

The Honjō Masamune sword, reportedly made by legendary swordsmith Gorō Nyūdō Masamune, was created sometime in the 13th or 14th century in Japan. Legends claimed that it was somehow imbued with the spirit of its masterful creator, but we do know that Masamune was renowned for his metalworking skills. The Honjō Masamune went through battle (gaining its name after it was won by General Honjō Shigenaga in 1561), then was continually sold and passed on until it landed in the Tokugawa family. By the 20th century, they were forced to give it up in late 1945, when post-WWII U.S. occupiers demanded the surrender of all swords (among other heirloom items).

From there, the Honjō Masamune became lost. It could have been carelessly destroyed, as some antique weapons were, though others were given to (or just taken by) American service members. Records indicate the Tokugawa's weapons were given to Sgt. Coldy Bimore of the Army's Foreign Liquidations Commission. But a twist arises: there's no official record of a Sgt. Bimore in that division, lending credence to a heist theory.

The recovery of other swords shows just how far these highly-prized objects can go ... or how close to home the missing sword may be. One highly decorated short sword was excavated in a Berlin cellar in 2022, while another Masamune sword was recovered from Japanese land in 2014 and confirmed to be the real deal.

Could someone in the US be holding missing Romanov Fabergé eggs?

Jeweler Peter Carl Fabergé was a favorite of the Imperial Russian Romanovs, starting with his creation of a bejeweled 1887 egg that Tsar Nicholas II gave to his wife Maria for Easter. Fabergé was commissioned to create several more, which were seized by Bolsheviks after the 1917 Russian Revolution. But Vladimir Lenin was said to be quite taken by the pieces and never destroyed the precious Fabergé eggs. However, Joseph Stalin had no compunctions about selling them off, starting in 1927. Some ended up in private collections and a few were recovered in unassuming shops, but a handful remain missing.

These lost imperial Fabergé eggs may also be squirreled away in an antique store, but where? Some have pointed to the U.S. as a likely destination. The evidence: three shipments of vaguely described but highly valued antiques that arrived in '90s New Orleans. From 1991 to 1992, the shipments came from the Soviet Union, then after the USSR's collapse, from Turkey. These three are collectively valued at $285 million in today's money and had manifests with similar language, referencing antiques over 100 years old.

Is this a smoking gun? Well, no, but original research conducted by Live Science revealed not only these documents but a long-standing practice of these sorts of mysterious import shipments. Though their contents remain undisclosed due to legal reasons, it's not hard to imagine a glittering Fabergé egg or two nestled in just such a cache.

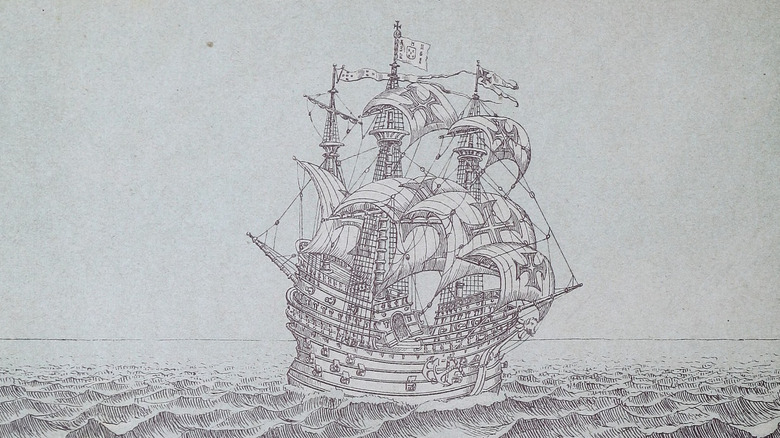

The Flor de la Mar treasure would be pretty waterlogged

In the world of wrecked treasure ships, the Flor de la Mar commands unique attention. It's not just that it was packed full of billions of dollars' worth of treasures taken from the Sultan of Malacca in 1510, but that it sank the next year and was never found. According to contemporary accounts, the many-times-repaired vessel was caught in a storm near Sumatra in November and split apart on the shoals. A bare few survivors out of an original company of 400 made it, but the treasure was lost. Could the riches — said to include 80 tons of gold, a bejeweled table, four life-sized solid gold lions, and 200 literal treasure chests that would give Long John Silver the vapors — still be there beneath the waves?

Plenty of speculation has been generated over the matter. Searchers have found tantalizing clues, like a silver coin from the right era off the Sumatran coast, as well as gold figurines and ballast stones on a reef, aided in large part by charts uncovered in Portugal's archives. Still, despite the attention and multiple search attempts in what's not Indonesian territory, no one's come across a busted ship with treasure scattered all about. It could be that this treasure was mostly washed away over the intervening centuries or lies buried deep in ocean muck.

King John's treasure may be buried in a marsh

King John doesn't have an especially good reputation. Even if all the Robin Hood legends framing him as a villain are made-up, the historical reality is hardly kinder. Not only did John lose major portions of inherited land, but his political flubs led to widespread rebellion and distrust.

Back in 1216, John was running from unruly barons, who had already pushed him to sign the Magna Carta and had now invited a French usurper to take the throne. With his supporters, the king was attempting to gather an army. In October, he and his entourage began to cross the Wash, the name for an area of coastal mudflats in Lincolnshire. But something went wrong with their calculation of the tides and much of his goods and party were lost in the mire. John escaped but, as contemporary accounts told it, was so upset that he grew ill and died.

What went into the Wash? Contemporary records mention treasure, and John was known to have some very nice jewelry pieces and religious objects, along with royal regalia that joined the list of mysteriously vanished crown jewels. Some had been sold off to pay for John's army-raising, but others may well have been carried with his group when it began crossing the Wash. Bits and pieces have been recovered from the spot in the modern day, but so far no golden horde has yet come to light, giving hope to future treasure-hunters.