Genius Inventors Who Died Incredibly Poor

Genius inventors may change humanity for the better, but it doesn't always bring them the riches they deserve. Just look at Nikola Tesla; his electrical innovations led to a brand that put a man at the top of the world's rich list. Yet for all his brilliance and lifelong toil, he died mired in debt — not exactly an ending befitting one of history's most memorable inventors. If the man who gave Thomas Edison a charged-up run for his money can end up with no money of his own, it can happen to just about any inventor on the block, and it has.

How do dazzling figures with such tremendous potential for lucrative futures instead end up broke? Oftentimes, a combination of patent registration snafus, poor investments, bad business decisions, and unfortunate life circumstances all contribute to such downfalls. There are even innovators who collected a little cash for their contributions, yet crashed out financially in the end. From Charles Goodyear, whose vulcanization process jump-started the rubber industry, to Marie Killick, whose gramophone needles brought music to our ears, these world-changing figures died surprisingly poor.

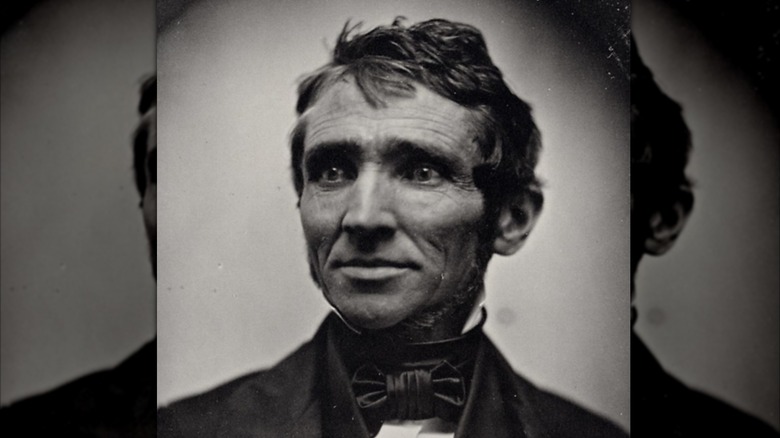

Charles Goodyear

Charles Goodyear's invention may have made it possible for the entire world to get from here to there safely, but he didn't clean up in the tire business like the brand bearing his name would suggest. When Goodyear came up with the idea for the process of vulcanizing rubber, which made it tough enough to resist wear and tear, he put the city of Naugatuck, Connecticut, on the map. There, the rubber industry flourished and led to the institution of the United States Rubber Company, one of the first stocks traded on the Dow Jones. U.S. Rubber developed Keds, the first rubber-soled sneaker and the original ancestor of sneakerheads' favorite footwear.

Goodyear's creation made a huge impact on the lives of people around the globe, but the inventor didn't seem interested in monetary wealth. Rather than chasing money, he preferred to continue with his work, allowing his innovations to help humanity rather than turn a personal profit.

The life of one of the world's most celebrated innovators came to an incredibly sad end when, in 1860, Goodyear learned his daughter lay dying in New York. He was unable to reach her before she passed and collapsed from shock, dying just a few days later at the age of 59. Despite getting the world up and running on an invention that would long outlive him, Goodyear died with $200,000 in debt; adjusted for inflation, this would be almost $8 million as of mid-2025.

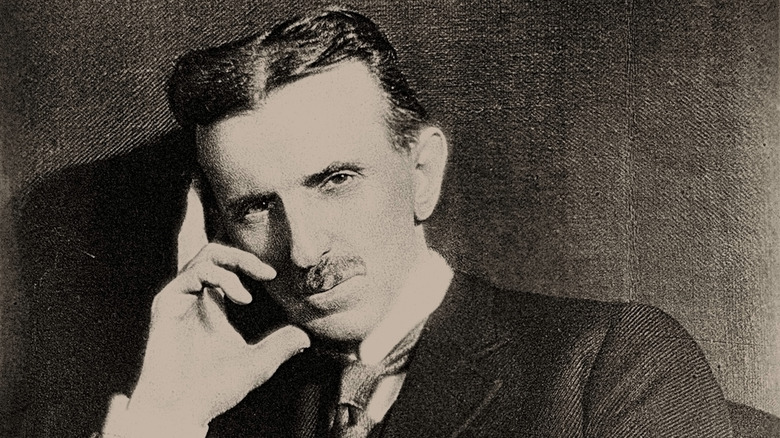

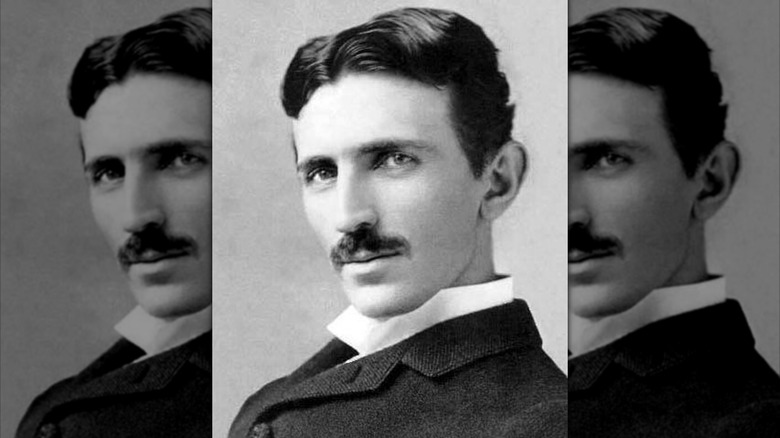

Nikola Tesla

His surname is now a byword for innovation and energy efficiency, and yet Nikola Tesla never came close to joining the billionaire's club like Elon Musk, the polarizing CEO of the company that bears Tesla's name. Tesla's postulations about the nature of electricity and the possibility of free access to energy worldwide may sound the opposite of profitable, but he imagined a reality driven by electrical power, and his electrical inventions changed the course of humanity.

Tesla worked for a while with Thomas Edison, a peer whose name would become synonymous with electrical light, before going on to create the Tesla Electric Light Company and to sell patents for his own work to Westinghouse. Even with his eye on starting a company, Tesla's mindset was far less commercially driven than the famously enterprising Edison, setting the two up for direct competition in the growing electricity industry.

Ultimately, Tesla became increasingly eccentric and reclusive; he drew attention from the FBI and even Russia for a rumored death ray that had a far different purpose. Following a coronary thrombosis, Tesla died poor and alone at age 86, but his legacy and the mysterious nature of his grand discoveries have become the stuff of legends in modern times.

Philo Farnsworth

The name Philo Farnsworth may not come to mind when you turn on your TV, but this inventor's insightful creation set us all on a path toward PBS, Netflix, and numerous true crime documentaries that everyone needs to watch. Farnsworth was a high school student when he hatched his idea for the television, which led to a lifelong quest for success that ascended quickly before taking a series of successive downturns.

So how does a peak thinker who paved the way for our modern screen-based society lose out on the lucre that should have rained down on him? For 10 years, RCA — one of the biggest names in the television set industry — paid a licensing fee to use the Farnsworth patent to produce televisions, a deal that ran out just as WWII was ending. The Radio and Television Manufacturers Association bestowed the label "Father of Television" on RCA's David Sarnoff, leaving Farnsworth in the dust.

After developing what would become one of the most important devices in the history of humankind, Farnsworth found himself in the middle of the 20th century without the riches he deserved. His company went bankrupt in 1970, and Farnsworth died of pneumonia the following year. His hard-luck life was captured in a 2007 Broadway play, "The Farnsworth Invention," but the production was shuttered due to the stagehand strike that year — yet another blow for this crucial and entirely underappreciated inventor's legacy.

Walter L. Shaw

If you've ever joyfully shirked your office responsibilities by diverting a call from your phone to your cubemates, you have Walter L. Shaw to thank. Shaw is responsible for bringing telephony into the modern age; in the mid-20th century, he conjured up the concept of call forwarding to properly connect parties. He also invented the voice-activated speakerphone to get whole groups in on the party line, as well as touch-tone dialing, the latter of which added speed and efficiency that was impossible with traditional rotary dialing. His creativity launched a thousand meetings that could have been emails (which would come much later, of course).

Shaw's developments came about while he was working for Bell Laboratories, but his promising career came to an unceremonious end when the inventor quit his job. Shaw believed he'd be able to take his innovations elsewhere thanks to a pending antitrust lawsuit intended to break up the phone monopoly, but AT&T won the suit and maintained its control over the industry. As a result, Shaw was unable to implement his ideas for his own profit.

In a dark twist, Shaw ended up using his telecommunication skills and creativity to help the Mafia, by hiding its bookmaking activities from the law by blocking wiretaps. These activities ended up tainting his reputation, rendering him a risky hire and barring him from future work with legitimate employers. He fell into poverty from which he never recovered and died in 1996.

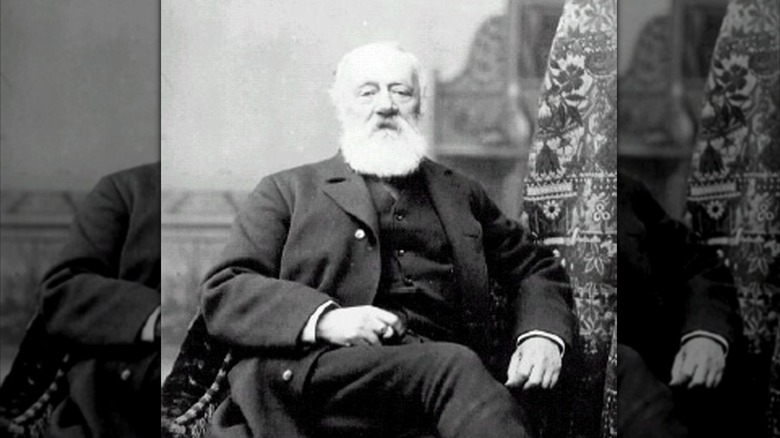

Antonio Meucci

Before Alexander Graham Bell got an inkling to create a wire-based communication system, Antonio Meucci was hard at work on the same idea. The Italian innovator was working at a theater in 1834 when he was struck with the brilliant notion of assembling a device that would allow the control room and the stage to communicate with one another. Years later, while living in Cuba, Meucci developed a so-called talking telegraph that brought voice to the world of telecommunications.

After moving to Staten Island in 1850, Meucci created a wire system throughout his home to speak remotely with his wife, Esterre, who was confined due to illness. This thoughtful innovation blossomed into the electromagnetic voice transmission device we all know today as the telephone. Meucci developed multiple models, all of which were stored in the lab where the inventor worked, until they all went mysteriously missing. Not coincidentally, another worker at this lab was Alexander Graham Bell, the man more famously credited with inventing the telephone.

Meucci ended up so heavily in debt that he couldn't afford the $10 fee to renew his patent. He eventually sued Bell in a case that went to the U.S. Supreme Court, but died in 1889 before it was heard. Though he died in poverty, Meucci was recognized in a 2002 resolution by the U.S. House of Representatives that acknowledged him as the true inventor of the telephone.

Marie Killick

Anytime you drop a needle on your favorite record — on a vinyl LP that uses a turntable — you're working with a version of the invention that Marie Killick added to the world. The realm of scratching, mixing, and DJ-ing would be a whole different scene without Killick cleverly devising a stylus that brought more clarity to sound produced by the gramophone, the predecessor to the modern record player. It was an innovation that was highly lucrative for Killick initially, but the riches weren't meant to last.

Killick may have made listening to music better for the rest of us, but her own path to success faltered and came to a discordant conclusion, which was directly related to her insightful invention. An electronics manufacturing company called Pye Radio Ltd infringed on her copyright and cut into her sales, initiating a 1953 lawsuit that became a landmark case in England.

As Killick's daughter Cynthia explains in her book, "A Sound Revolution" (via a website dedicated to Marie Louise Killick's story), Killick was set to rake in millions if the lawsuit went her way. But litigation dragged on, and though she won the case, Killick was driven into bankruptcy, which prevented her from receiving the awarded compensation. In her own words, the inventor said, "If I had won my judgement to a conclusive and successful end, I should have been a very rich woman, and this terrified me, because I would not have found favour with God." Killick died homeless and impoverished in 1963.

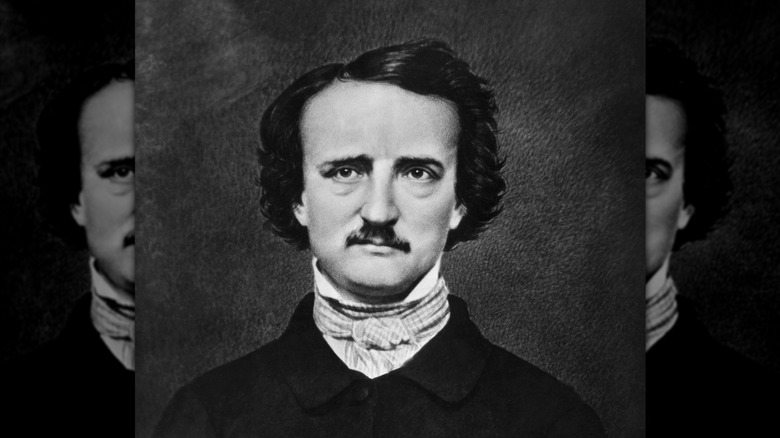

Edgar Allan Poe

You may be familiar with his spine-tingling stories and chilling poetry, but in Edgar Allan Poe's tragic real-life story, the author also invented one of the most important literary forms ever imagined. Poe's "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" is considered the first popular detective novel, a spark that lit the fuse for luminaries like Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, and, more recently, James Patterson to create the crime novel explosion that persists today. If you love the exploits of resourceful characters like Hercule Poirot or Benoit Blanc, you have Poe to thank for setting the genre in motion.

Poe's development expanded the world of literary genres and opened readers up to the concept of the gothic crime-solving sleuth figure, which branched off into everything from cozy mystery tropes to hard-edged true crime fodder. This literary giant's fertile imagination had an indelible impact on the publishing industry, which has generated a never-ending cash flow as a result.

Poe's unending influence on modern literature is worthy of a much greater fortune for the man who invented one of publishing's most enduring and profitable formats. Sadly, as with many artistic geniuses through the centuries, Poe struggled to make ends meet financially; according to The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore, his annual salary for 1835 was determined to be a paltry $624. The year he died, he was likely to have earned less than $300.

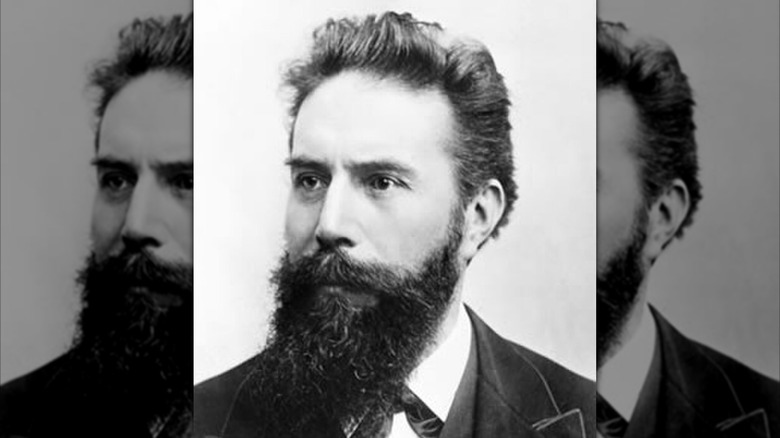

Wilhelm Rontgen

Wilhelm Röntgen wasn't an inventor in the traditional sense of the word, but the German physicist's studies caused a seismic shift that would forever alter how we would see the world. It was Röntgen's work with cathode ray tubes and charged gases that resulted in his discovery of X-rays. He created what he called röntgenograms, which were the earliest X-ray images of inanimate objects; his wife's hand served as the first human subject. Röntgen called them "X-rays" due to their unknown nature, and the name stuck.

The earthshattering discovery led to accolades from the academic and scientific worlds, though the acclaim didn't do much to alter Röntgen's humble, nature-loving personality. He tended to work alone, taking friends on mountain adventures at his summer home in the Bavarian Alps and tinkering on his contraptions in solitude, preferring to work alone.

Though the man who pioneered the science behind how X-rays work was showered with money and appreciation during his lifetime, he wasn't destined to retain his riches. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics in 1901, an achievement most would consider the pinnacle of their lifetime. However, Röntgen chose to give away the prize money awarded by the Nobel Foundation. He developed intestinal cancer and died in poverty in 1923, having changed the world permanently and for the better.

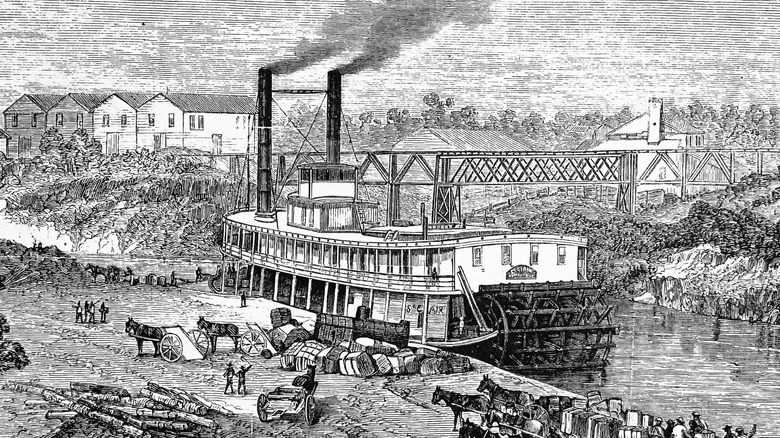

John Fitch

The story of the Mississippi River would have been woefully incomplete without the steamboat, and the steamboat would have been far less possible without John Fitch. His fertile imagination dreamed up an engine that utilized steam to propel waterborne vessels, and it became the basis of his steamboat business. Although figures like Robert Fulton had greater success, Fitch's was the first of its kind in the world.

From initial idea to finished plans, it took only six months for Fitch to bring his steam engine to the American Philosophical Society, the predecessor to the U.S. Patent Office. Figures like George Washington and Benjamin Franklin declined to invest in his steamboating business, so Fitch pulled himself up by the bootstraps, built his dream ship, and began toting passengers between Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Unfortunately, he was unable to attract enough business to stay afloat, and Fitch's competitor, Robert Fulton, turned out to be the man whose steamboats changed the world.

The once-promising inventor's failed enterprise left him penniless. Fitch began to drink excessively, and eventually died by suicide in 1798 at the age of 55. Despite his lack of financial success, his achievements are honored in The John Fitch Steamboat Museum in Warminster, Pennsylvania, where Fitch made his dreams come to life.

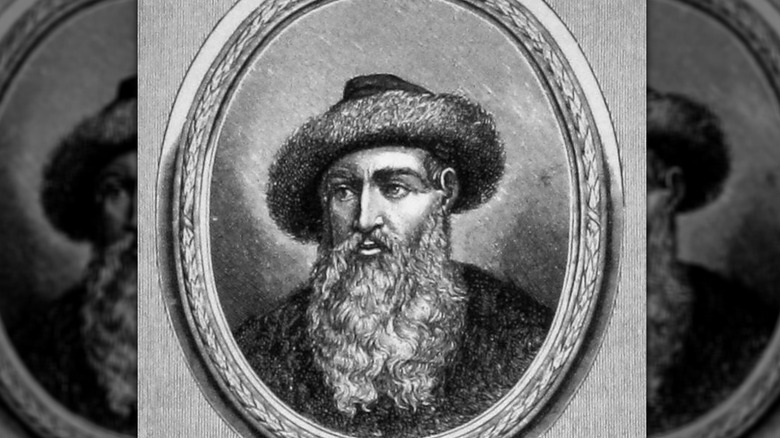

Johannes Gutenberg

One of the most important figures in human history, Johannes Gutenberg was the genius responsible for inventing the ancestor of the modern printing press in 1455. This revolutionary invention allowed for the mass production of printed books, opening access to literature to entire generations of people, instead of a privileged elite who could afford expensive handwritten works. Gutenberg's contraption got the whole concept of publishing up and running, starting with, of course, the Bible, which was a surefire way to make money by printing what would become the best-selling book in the world.

Gutenberg's press was a contraption that cleverly combined several elements. He merged Asian printing blocks and his own version of oil-based ink with the simple turn-screw press used by farmers to express grape juice and olive oil. With his movable type facing and metal letter molds, Gutenberg assembled letters into words using a type tray. The result was the beginning of a self-printed book that could be produced much quicker than the archaic handwritten method allowed.

There was a darker side to Gutenberg, though: his reputation as a shyster. Though he honestly created what would become one of the most important machines in history, he had a penchant for grifting money from others, even borrowing funds for his printing press. He found no fortune despite his ingenuity and died poor, most likely in 1468.