What Would Happen If The Earth Lost Its Deserts

What if our planet lost all of its deserts? Such an idea may sound far-fetched, but there was once a time when the vast Sahara Desert was a lush, green expanse. This era, which lasted from about 11,000 to 5,000 years ago, is sometimes called the Green Sahara or, perhaps less poetically, the North African Humid Period. In fact, the Sahara won't always be a desert, as it has gone through so-called "greenings" hundreds of times over the last 8 million years, largely because of the way our planet wobbles about on its axis over millennia. This means that it's not beyond the pale to imagine a significant ebb of deserts happening again, though if the estimates of these greenings occurring every 21,000 years are correct, we've got another 10 millennia or so to go.

This begs the question: what would happen to Earth if all its deserts went through another round of this greening? Would we fare for the better, worse, or just different? As a species, we're increasingly learning that things like global ecosystems and the climate are complicated beasts with many interrelated factors. If we lost all of this environment, it wouldn't just mean we would miss out on delightfully creepy desert stories — rather, there's a lot more potentially at stake. Indeed, there would be some surprising knock-on effects that would prove to be challenges all on their own, from major climate disruptions to large shifts in evolution and biodiversity.

The planet's air circulation would change dramatically

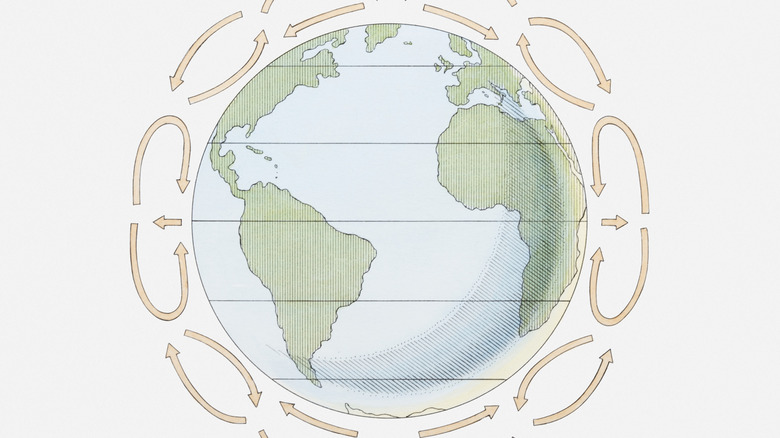

About 20% of the Earth's surface is currently desert; many of these environments are located within 30 to 50 degrees in latitude, while equatorial regions tend to be warm tropics with plenty of rainfall. At the equator, sunlight hits the planet most directly and warms the air, which then rises. It then begins to cool off and can't hold onto much water anymore, leading to rainfall below.

But the air, now much cooler and drier, continues its motion. It circulates through a weather pattern known as a Hadley cell and begins to move towards desert regions further north or south. When it hits those latitudes, it begins to sink again, warming up. This "thirsty" air picks up water along the way, leaving the deserts below all the drier. This is a simplified explanation of a complicated process, but it serves for understanding these broad air movements.

When places like the Sahara had far more vegetation, Hadley cells expanded into other latitudes and picked up more water, which meant that seasonal monsoon rains were not just more widespread, but also stronger. This would have affected the prevailing wind patterns called trade winds, which have a major role in forming hurricanes and tropical storms (not to mention shipping lanes). With Hadley cells shifting to different latitudes, new regions would have to face these storms — or face them again, as analysis of ancient sediments indicates. Moreover, airborne dust from the Sahara has been found to tamp down some Atlantic storms; without that, more intense or more frequent storms would likely arise.

Unique ecosystems would be lost

Many people have a negative view of deserts, with University of California at Davis history professor Diana Davis using the term "arboreal centrism" to describe the prejudice (via Noema). But while desert environments can be uniquely harsh, they are also uniquely diverse and contain ecosystems that simply can't be replicated elsewhere. If deserts were to undergo a re-greening process, those unique ecosystems would face serious challenges. Furthermore, greater biodiversity results in more resilient ecosystems, more resources for us and other animals, and provides an important bulwark against the effects of climate change.

In the ancient past, the animals that thrived in the Sahara were dramatically different from the desert-dwellers of today. Archaeological research in Niger, a West African nation, shows that the Saharan Gobero site was once host to crocodiles, hippos, giraffes, and elephants, as well as a population of humans. While humans are still making a life in parts of the Sahara, you're sure not going to see hippos freely roaming around.

Large deserts can also act as barriers to other, less well-adapted species. A now-green desert may act like an open gate, allowing animals and plants to travel farther into new territory and changing previously untouched ecosystems. Research published in Nature Communications shows that this "open gate" phase of the green Sahara had marked effects on how species moved through Africa and set the stage for their future evolutionary paths — including humans who traveled through the region 120,000 years ago.

Animal populations would change

With green deserts, some animals would need to undergo major changes to survive. Consider the fennec fox, a canid from the intense deserts of North Africa and parts of the Sinai and Arabian Peninsulas. Its huge ears help it shed excess body heat, and its furry paws are well-suited to padding through hot, shifting sands. While its thick fur can also help it deal with cold desert nights, research indicates that fennec foxes can experience cold stress starting at just 50 to 68 degrees Fahrenheit (about the average temperature savannas experience in the dry season today). However, small foxes also utilize behavioral changes to manage heat, so a greenified desert may not necessarily be a species-ending event, even if it demands major adjustments.

Other animals might have to do hardly anything. Monitor lizards include species that have set up shop in punishing deserts across Africa, Asia, and Australia, while others are doing just fine in far more tropical environments — heck, they can even swim. This group includes the Komodo dragon, the largest lizard species that, though it's only found in a small Indonesian territory, lives in that region's diverse array of grasslands and forests with high humidity. Desert-adjacent monitor lizards would likely have little problem moving into a savanna-like green Sahara.

Furthermore, in the far-distant past of about 56 million years ago, a lush Antarctica (now a chilly desert) was host to marsupials and perhaps even a few sloth relatives among many more plant and animal species — a stark contrast to its low biodiversity today, after desertification and cold temps pushed many species out.

Green deserts are linked to major changes in climate

Today, you may hear about "desertification," where previously fertile lands become arid through a combination of weather changes (like increased droughts and flooding) as well as nutritional loss via soil degradation. The idea of re-greening desertified places is naturally interesting, but it's not clear just how that would affect climate. Research suggests that at least some major deserts could act as carbon sinks that hold on to carbon dioxide, which would otherwise be a planet-warming atmospheric greenhouse gas. However, it also appears that savanna environments similar to the ancient green Sahara can also hold onto quite a bit of carbon.

Yet green deserts can point to more climate woes. Both the Arctic and Antarctic regions qualify as deserts because they receive very little precipitation — in fact, Antarctica is often considered the world's largest desert. Yet these places also contain large masses of ice and currents, such as the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC), which have a complicated effect on air circulation and global weather patterns.

Consider that, about 90 million years ago, Antarctica was once a lush landscape after increased atmospheric CO2 melted ice caps and raised global temperatures. While scientists note that more abrupt climate changes wrought by human activity complicate predictions, a green Antarctic desert would surely play into a future climate effect. Modern observations have found that warmer seas create an even faster and rougher ACC. Scientists have also noted increased atmospheric CO2 via melting permafrost in the Arctic's very low-precipitation tundra, which could lead to an even more intense rise in global temperatures.