After Nearly 100 Years, Archaeologists Finally Found The Missing Part Of An Ancient Egyptian Statue

In 1930, the Egyptologist Gunther Roeder was leading a German team in what would become a decade-long seasonal excavation at the site of the ancient Egyptian city of Hermopolis Magna, also known as Khemenu (now El Ashmunein). Among the many discoveries Roeder and his team made, which included most of a massive temple site, was the bottom half of a large statue that turned out to be that of Ramses II (also written Ramesses II). This long-reigning pharaoh from the 13th century B.C., known as Ramses the Great, was a warlike ruler who commissioned many statues of himself, and Roeder's discovery was one of many that remain today across Egypt.

For nearly 100 years, the statue fragment remained just that until early 2024, when a joint Egyptian-U.S. team unearthed the rest of the statue in the same area where Roeder found the bottom half. When it was first carved, it would have stood almost 23 feet high, and features the pharaoh seated and wearing a dual crown indicating his rule over both Upper and Lower Egypt.

Ramses II's image was pervasive in ancient Egypt

Ramses II ruled for 66 years from 1279 to 1213 B.C. during the New Kingdom of ancient Egypt, fathered a mind-blowing 100-plus children, warred with the neighboring Hittites and Libyans, and is considered the most powerful ruler of ancient Egypt. As one of the richest Egyptian pharaohs, he was able to build extensively. He constructed a new capital city called Pi-Ramesse and built numerous temples, including a funeral temple for himself known as the Ramesseum. He also built himself the largest tomb in the Valley of the Kings, along with tombs for his wife Nefertiti and his mother. There are at least 350 known statues of Ramses II, and he often resorted to having existing monuments altered to glorify himself.

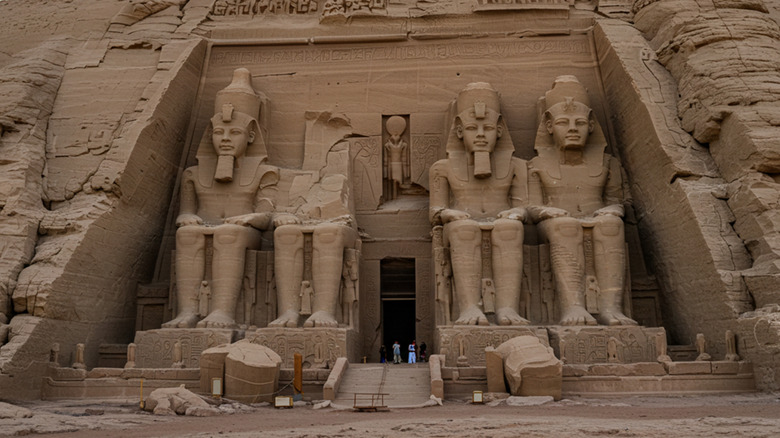

From the northern ancient Egyptian city of Memphis — near present-day Cairo — to more than 750 miles south at Abu Simbel, Ramses II's visage can still be seen more than 3,000 years after his death. Gunther Roeder and his team's 1930 discovery of the bottom half of a statue, and the finding of the top half some 94 years later, may be impressive but not surprising, considering how much time and effort this great pharaoh went to have his likeness reproduced.

The 1929-1939 German excavation

Beginning in 1929, Gunther Roeder, who was the director of Germany's Pelizaeus Museum, and his team began to excavate the ancient city of Hermopolis Magna. As work progressed, Roeder was struck by the number of ancient artifacts. "Everywhere we begin to dig, we make interesting finds," Roeder recalled (via The Flint Journal). "The ground is filled with monuments." Among these archeological treasures was the bottom half of the Ramses II sculpture.

If you're making the connection between 1930s German-led archeological excavations of ancient artifacts and a certain Indiana Jones film, hold onto your fedora. There is indeed a nugget of truth to "Raiders of the Lost Ark," the action film about a Nazi-led hunt for magical archeological treasures. At some point, Roeder, while working to unearth important archeological finds, became a member of the Nazi party. For that reason, he lost his position as the head of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin following the end of World War II, but was exonerated in 1948.

Archeologists found the other half in 2024

In January 2024, a joint Egyptian and U.S. archaeological team from the University of Colorado Boulder was excavating at Hermopolis Magna looking for an ancient Egyptian New Kingdom religious site, and instead uncovered the top half of a statue of Ramses II. When discovered, it was face down in the ground and had to be excavated. The scientists determined the 12.5-foot-tall limestone piece fit perfectly with the lower half that Gunther Roeder's team discovered in 1930.

The arguably more interesting half of the sculpture includes the pharaoh's well-preserved face and double crown, featuring a cobra that represents royalty, as well as hieroglyphs on the back praising Ramses II and traces of blue and yellow pigment. While the discovery didn't solve any ancient Egyptian mysteries, it remains important since it will now allow the archeologists to have a complete statue of Ramses II. It also gives them a better understanding of the breadth of how the pharaoh was represented during his long reign. Plans are in the works to possibly rejoin the two halves of the sculpture, ending a nearly 100-year-old mystery of this over 3,000-year-old image of one of ancient Egypt's greatest pharaohs.