How This WWII Crew Escaped A Sunken Submarine

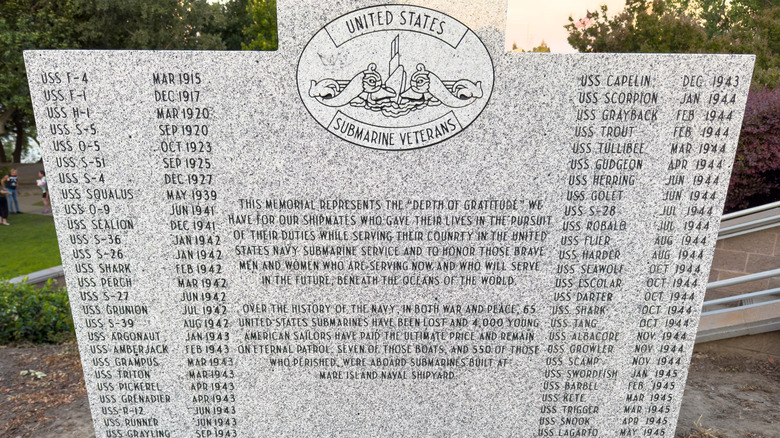

Serving on a submarine in World War II is up there with some of the most dangerous military jobs in history. Many World War II submarines went missing and were never found, with no survivors to supply information about what happened. Other times, the men (and up until well into the 21st century, it was only men) serving on subs that ran into trouble managed to escape, with harrowing tales of survival.

The sinking of the USS Tang — and the terrifying attempts to get out of it alive — is one of the most nightmarish World War II battle stories most people haven't heard. Out of a total of 87 souls on board, only nine survived to tell the world what happened on October 25, 1944, in the treacherous ocean waters off the coast of China. For the survivors, though, it was only the beginning of their nightmare, which would last until the end of the war, almost a year later.

While the overwhelming loss of life was undeniably tragic, the fact that anyone trapped on the USS Tang survived is almost miraculous. Here's how a lucky few members of this World War II crew escaped a sunken submarine.

The Tang was the most successful U.S. submarine ever

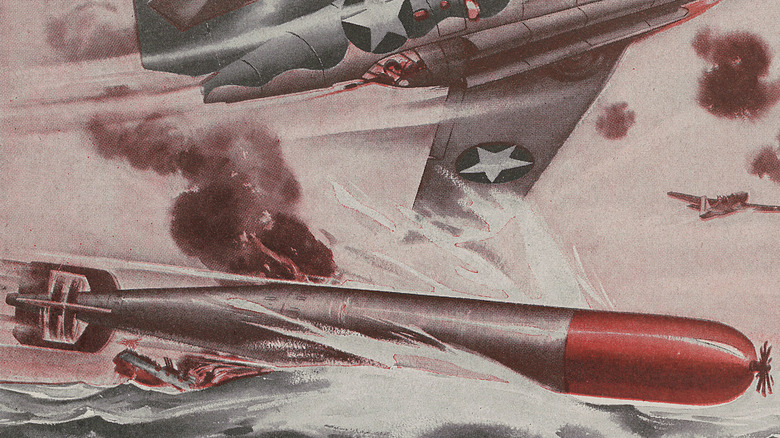

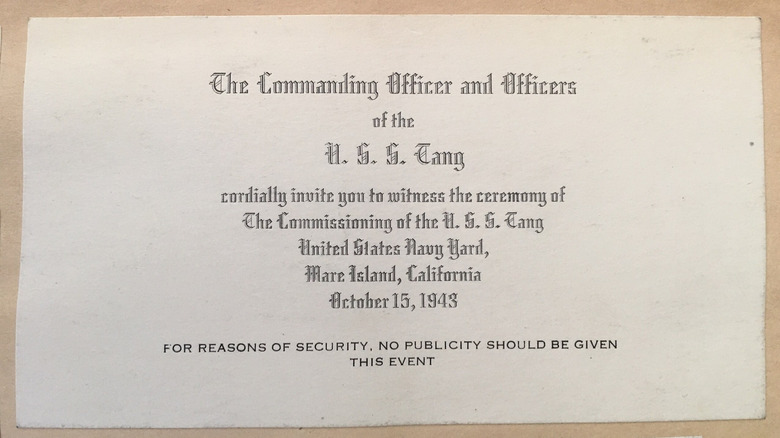

Up until its tragic end, things could not have gone better for the USS Tang and its crew. The submarine headed out on its first war patrol on January 22, 1944. Even in more modern crafts, it's really hard to serve on a submarine. But the crew of the Tang not only dealt with the issues that arose from living in a small metal tube under incredibly stressful circumstances, they managed to thrive under them. Despite the submarine's short time in service, when it comes to the number and tonnage of enemy ships sunk, no sub comes close to the lethality of the Tang. It was not only successful at killing the enemy, however; during the Tang's second war patrol, it rescued 22 Allied pilots whose planes had been shot down (pictured), a record that still stands today.

The Tang's fifth and final patrol was its most successful of all. Submarine Force Commander Vice Admiral Charles Lockwood called it "one of the greatest submarine cruises of all time," according to American Submariner. The submarine crew's success continued until literally the last seconds. In its final 24 hours before disaster, the Tang sank 10 boats in total from two different Axis convoys.

Then it went wrong

It was not an enemy ship that defeated the Tang, but one of the submarine's own torpedoes. While sinking your submarine with your own torpedo might sound almost as embarrassing as the time a German U-boat was sunk by a toilet, it is really a terrible stain on the U.S. Navy during World War II, and was a result of its apparent lack of concern over a weapon those in charge knew was faulty. The Tang was equipped with Mark 18 torpedoes. While these were a vast improvement over the almost comically faulty Mark 14 torpedoes that U.S. submarines had begun the war using, other submarine crews had also experienced extensive faults with the Mark 18s, and the Navy was well aware of the issues.

It was the most successful night of the Tang's fifth war patrol, having sunk seven boats already, and the sub was down to the final two of her 24 torpedoes. The 23rd hit its target, but when the 24th and final torpedo was launched, it circled back around to the sub. The captain tried to maneuver, but there was no time. Just 20 seconds after the weapon was launched, it struck the Tang in a fatal blow.

Shortly after the war ended, an AP correspondent spoke to the Tang's Lieutenant Commander Lawrence Savadkin, who said, "I was in the conning tower when the torpedo hit. It was like the world coming to an end" (via World War II On Deadline).

The impact of the sub's own torpedo was catastrophic

The impact of the Tang's own torpedo killed some of the men on board instantly, but as the submarine sank like a stone to the bottom of the ocean, there were still dozens of survivors trapped inside. Just because they were alive did not mean they were in a good way; the force of the impact resulted in broken bones and other injuries. Even more concerning was the fact that the survivors were now trapped at the bottom of the ocean in a craft that was both rapidly flooding and erupting in flames.

All the men in three of the submarine's compartments drowned. Others barely avoided that fate. "Water was pouring in from the open control room doorway," survivor Jesse DaSilva told POLARIS (via SS563.org). "Two or three of us seized the door and with a great effort forced it shut." While they had managed to seal themselves off safely for the moment, more than half of the remaining 30 men alive on board were trapped in an increasingly dangerous situation.

"There were about 20 of us in the crew's quarters and the mess," DaSilva said. "We knew that we couldn't remain there long because of chlorine gas (from the flooded batteries). We also knew our only chance to escape was through the forward torpedo room. But we had to go through the control room to get there." And the control room was rapidly flooding.

The crew's desperate escape attempt was delayed

One submariner who was not with the majority of the other survivors was already on the surface of the ocean. "I went down with the boat," William Leibold said. "I remember very clearly there was a distinct bump that made me start to swim back to the surface. It may have been when the stern hit the bottom" (via Friends of the National World War II Memorial). Miraculously, he made it, but once he was on the surface, he could hear explosions, indicating anyone still alive on the Tang was in even more danger: The Japanese ships were dropping depth charges.

The submariners in the Tang were not in a situation that their bodies could physically handle for long. The sub was on the bottom of the ocean, compartments were flooding, and a fire was coming dangerously close to the room where the majority of the survivors had taken shelter. Jesse DaSilva told POLARIS (via SS563.org), "... the air worsened. The lights were getting dimmer, and we were using battle lanterns. The bulkhead near the forward battery grew so hot that the paint began to melt." But the depth charges meant they had to wait for the chance to escape — and that was assuming one of the depth charges did not hit its target, killing everyone left in the submarine.

They passed the stressful time by destroying classified documents, waiting for the explosions to cease.

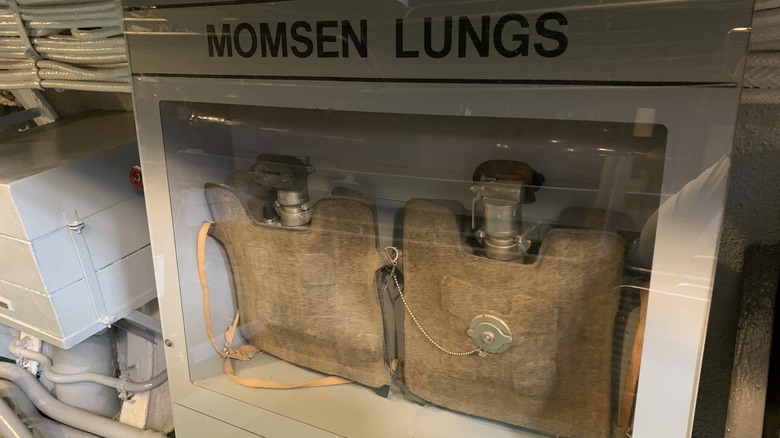

The only known successful use of a Momsen lung

Invented in the decade before the war, a Momsen lung was a very primitive safety device. It was essentially nothing more than a bag of oxygen attached to the face, and it had never been used successfully before. But now it was the only hope for the Tang's surviving crew. The process of preparing the lung and coming to the surface took ages as they tried to avoid getting potentially deadly air bubbles in their bloodstreams. Clayton O. Decker told the Oakland Tribune (via World War II On Deadline), "I was the first to go through the hatch with the lung. I floated for an hour before the others followed."

It also took an intense toll on the body. "I was the third one out. Someone had already let out the buoy line from previous escapes, and I wrapped my feet around the rope and slowly let myself up 10 feet at a time, stopping to count to 10 each time," Jesse DeSilva told POLARIS (via SS563.org). "About a third of the way up, breathing became difficult, but the problem went away as I continued up." Of the 30 men in the torpedo room, only 13 were physically able to attempt to surface.

A few survivors escaped through other means. "I managed to feel my way to an open hatch and was lucky enough to find a huge air bubble which helped me to surface," Lieutenant Commander Lawrence Savadkin told the AP. "I must have swum 100 feet to reach the surface."

A total of 78 crew members died

The 78 men who lost their lives died over the course of the night in various horrible ways. Some were killed in the initial blast, some drowned, and some were burned. Others were not physically able to handle the escape attempt, and some died while making that attempt. One of the victims, Rubin MacNiel Raiford, lied about his age to enlist and was just 15 when he died. He is believed to be the youngest American to die in battle during World War II.

Some of those who made it to the surface were lost. "Two more men came up shortly after I did," Jesse DaSilva told POLARIS (via SS563.org). "One was our pharmacist's mate, who surfaced nearby, but he was having difficulty breathing, so we held on to him. Another one, a steward, came up at a distance. I considered myself a good swimmer and started toward him, but he disappeared before I could reach him." The survivors clung to a buoy, hoping for a miracle.

Only nine of the Tang's crewmembers survived: Commander Richard H. O'Kane, Lieutenant Commander Lawrence Savadkin, Lieutenant Junior Grade Henry J. Flanagan, Radio Technician 1st Class Petty Officer Floyd Caverly, Boatswain's Mate Petty Officer 1st Class William Leibold, Motor Machinist's Mate 2nd Class Petty Officer Jesse DaSilva, Motor Machinist's Mate 3rd Class Petty Officer Clayton Decker, Torpedoman's Mate 2rd Class Hayes Trukke, and Torpedoman's Mate 3rd Class Pete Narowanski.

Almost a year after the disaster, Savadkin still seemed shocked, telling a reporter: "Nine in all survived from a complement of [87] men. I don't know why more didn't get out."

A Black submariner who initially survived did not receive recognition

While the U.S. Navy was not strictly segregated in the same way the Army was, with only a handful of exceptions, Black men were only allowed to serve as steward's mates, meaning they were assigned to cook, clean, and do other menial duties. Steward's mates were almost always men of color. On October 5, 1940, the New Pittsburgh Courier, a Black newspaper, published a letter signed by 15 Black sailors, warning other Black men not to enlist, as they would merely be "seagoing bellhops."

But Howard Madison Walker signed up for the Navy at 18 despite facing rampant discrimination as a Black man. Assigned to the Tang, he was not even listed by name on the Navy's records, but as the submarine's "Negro steward" (via the Bowling Green Daily News).

Walker was unable to put on a Momsen lung because he had broken his nose during the Tang's disastrous accident, but he risked going to the surface just holding his breath. While he made it, surfacing that quickly most likely gave him the bends, and other survivors noted he was in distress. Walker died before he could be rescued. Every man who died on the Tang received a Purple Heart, as is standard. However, Silver Stars are given for gallantry. Every man known to have escaped the Tang and made it to the surface alive — even if they were lost after that — was awarded the Silver Star. Every man, that is, except Walker, who was not awarded a Silver Star because of his race.

Nine survivors were captured by the Japanese

Hours after the sinking, once it was light, the nine surviving members of the Tang's crew were rescued by a Japanese ship. While being plucked out of the ocean by the enemy is not ideal, the men of the Tang soon realized they were going to be treated worse than other Allied prisoners on that particular ship — for a very understandable reason. In his official report on the sinking (via "Clear the Bridge!: The War Patrols of the USS Tang"), Commander Richard O'Kane explained, "The Destroyer Escort which picked up all nine survivors was one of four which were rescuing Japanese troops and personnel. When we realized that our clubbings and kickings were being administered by the burned, mutilated survivors of our own handiwork, we found we could take it with less prejudice."

The Tang's survivors spent the rest of the war, about 10 months, in Japanese prisoner of war camps. They were malnourished, subjected to the elements, and beaten. Pete Narowanski had several caps knocked off his teeth from the beatings he took, but after the war ended, the VA refused to cover the cost to get them fixed. "They told me it wasn't a service-connected injury," he told POLARIS (via SS563.org). Despite this ill-treatment, all nine survived and were liberated at the end of the war.

Families of the crew could not tell anyone what happened for months

Shortly after the war ended, the Tang's commander lied to a Mutual Broadcasting correspondent about what happened to the submarine. "Suddenly, there was a terrible explosion and our stern was blown off," Richard O'Kane said (via World War II On Deadline). "I never knew what hit us. It must have been a mine. It was a very heavy blast, and it broke the backs of many of my crew." Of course, he did know what had happened, and so must have chosen (or been instructed) not to say. It is an example of the secrecy that was still surrounding the disaster even after the relevant conflict had ended.

Due to the confidential nature of war maneuvers, the previous year had been extremely difficult for the families of the Tang's crew, one of desperation for answers and the inability to tell anyone what little they did know regarding their missing loved ones. The loss of the Tang was a government secret that it didn't want accidentally made public. They did not even announce its sinking until more than three months later.

Even long after there was no possible national security reason to keep details of the sinking classified, the government was not overly forthcoming with the crew's loved ones. Some families were still finding out painful details of their relatives' last moments decades later.

The captain was awarded the Medal of Honor

The captain of the Tang, Richard O'Kane, was one of the nine survivors. He wrote a book on his experiences during World War II, "Clear the Bridge!: The War Patrols of the USS Tang," which is the definitive account of the disaster. Kane was awarded the Medal of Honor for his final war patrol; the success of the Tang's various patrols before the tragedy led to Kane being considered the most successful submarine commander of the entire war.

It almost seemed like fate had it in for O'Kane, or at least any submarine he commanded. He served on three submarines during the war. First was the USS Argonaut, which he left for the USS Wahoo in 1942. Four months later, the Argonaut was attacked by the Japanese; all 102 crew members died, making it the largest loss of life on any U.S. Navy submarine during wartime. O'Kane was on the Wahoo until leaving it to command the still-under-construction USS Tang in July 1943. Three months later, while on its seventh war patrol, the Wahoo was lost, along with the 80 men on board.

In 1998, at the launch of a ship named in his honor, Richard's widow, Ernestine O'Kane, told the AP, "The hardest thing for him the rest of his life was that he came home and his men didn't" (via the Maine Sunday Telegram).

The disaster is recreated for visitors to the National World War II Museum

Seven years after the USS Tang (SS 306) sank to the bottom of the ocean, another U.S. Navy submarine was given the same name in its honor. At the commissioning of the new USS Tang (SS 563), the lives of those lost on the original were honored in the program by executive officer W.R. Anderson: "Fate cut down your fighting submarine at the very hour you deserved the greatest laurels of victory. We cannot replace you, rather, we hope that we shall capture some of your skill, some of your devotion to duty and country, and some of your gallantry" (via All Hands).

Think you would have had enough skill, patriotism, and gallantry to survive? For those who want to experience the unbridled terror the submariners must have felt during the Tang disaster, they can visit New Orleans, where there is an interactive exhibit at the National World War II Museum. "Final Mission: USS Tang Submarine Experience" immerses groups of 27 people in sights, sounds, and motion similar to what the Tang crew went through. Each participant is assigned the name of a real submariner, some perform appropriate duties in the exhibit, and at the end, they discover if the man they represent lived or died.

Knowing that, at most, nine patrons out of the group of 27 could "survive" must bring home how great the loss of life was in a group of men who numbered 60 more than that.