Nightmarish World War II Battle Stories Most People Haven't Heard

Looking back today, it's impossible to fathom just how intense the combat was during the Second World War. The war officially began in 1939, but it was not until the attack on Pearl Harbor in late 1941 that the United States became involved. From then until September 1945, when the Japanese surrender was complete, American soldiers fought in the war throughout Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Pacific.

Of the almost 18 million Americans who served during the war, 38% of them were volunteers and 62% were draftees, with almost 3/4 of them making their way to fight overseas. Of the men who fought, only a very small number, 5,000, have been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, and just 473 have been awarded the Medal of Honor. The Distinguished Service Cross and Medal of Honor are the two highest United States Military awards that can be earned, and they are reserved only for those who showed incredible heroism under fire.

By now, most veterans of WWII have sadly passed on, but their legends are still alive in the form of books and media that pass them down to younger generations. There are so many horrific accounts that it's impossible to learn about them all, and these are the nightmarish World War II battle stories that most people haven't heard.

Hale's Handful

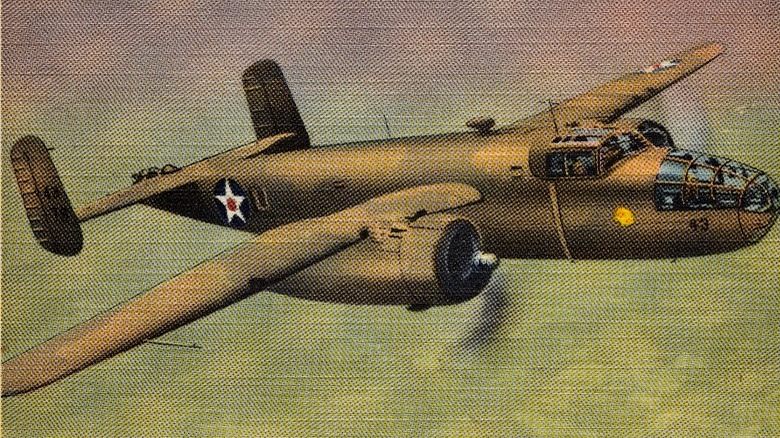

Compared with the highly advanced aircraft available today, the planes of the Second World War were pretty primitive in design. They handled rougher, did not have the GPS-based navigation systems we have today, and looked bulky and cumbersome instead of sleek and stylish. That made the men who fought in the United States Air Force during WWII some of the bravest in the entire military.

During the war, the Seventh Air Force was primarily stationed in the Pacific, and they were tasked with defending several American islands. They acquired the nickname of "Hale's Handful," due to their commander, Maj. Gen. Willis Hale, and began fighting in combat in 1943. As part of the outfit, the 396th Bomb Squadron was launched on January 25, 1944, to bomb the Maloelap Atoll in the Pacific. The attack mainly consisted of B-25 aircraft, one of which was co-piloted by 2d. Lt. Malcolm Knickerbocker, a 21-year-old college kid. However, the Japanese were ready for the attack and had anti-aircraft (AA) guns waiting.

While flying towards the atoll, Knickerbocker's B-25 was hit by flak from the guns, severing his leg and eventually proving fatal. Still, he refused to abandon his crew, fighting through the injury to continue flying the plane, despite hemorrhaging blood. With only a makeshift tourniquet to stop the bleeding, Knickerbocker managed to fight through his wounds until the aircraft was safely headed back, at which point he died. For his heroism, Knickerbocker was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Ewart Sconiers: Pilot in Training

Sometimes when fighting a war, soldiers must go above and beyond the call of duty to keep themselves and their comrades alive. Few have exemplified that ethos more than former Lt. Ewart Sconiers of the 8th Air Force. On August 21, 1942, Sconiers was on a B-17 aircraft participating in a bombing run over Rotterdam, Netherlands. Unfortunately, the B-17 was hit hard by Luftwaffe fire, resulting in the death of one of the pilots and severely wounding the other.

The surviving pilot, 2d. Lt. Richard Starks, was able to collect himself and called Sconiers to take control. Despite having only minimal training as a pilot and the plane being down two engines, Sconiers was able to get control and successfully land it back in England. He had to remove the pilot's body to access the cockpit, and he also helped Starks to put his oxygen mask back on. Upon landing the duo became quasi-celebrities, and both were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for their efforts.

This proved to be the last mission of the war for Starks, who required several surgeries to recover from his wounds. He eventually became an Air Force instructor, teaching young pilots the ins and outs of the same B-17s he used to fly (via the American Air Museum). Sconiers would become a prisoner of war (POW) after his B-17 was shot down a few months later, and he passed away in a POW camp in Germany under mysterious circumstances.

The incredible courage of Jack Lummus

The Battle for Iwo Jima was one of the most harrowing of the Pacific Theater, leading to the deaths of more than 27,000 combatants. Of all the horrific and stunning stories from the battle, the tale of 1Lt. Jack Lummus is especially poignant. Prior to fighting in the war, Lummus had a successful college baseball career and had also played for the New York Giants in the NFL.

However, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Lummus joined the Marine Corps (after previously washing out of the Army Air Corps), and almost exactly three years later he saw his first action at Iwo Jima in February 1945. Fighting as part of the 27th Marines of the 5th Marine Division, Lummus was the leader of Easy Company's third rifle platoon.

While at the head of an attack early on the morning of March 8, Lummus was mortally injured when a land mine exploded as he was advancing (via "Iwo Jima: Legacy of Valor" by Bill D. Ross). He had previously survived two grenade explosions and had single-handedly taken out a Japanese squad before stepping on the mine. Remarkably, Lummus managed to keep fighting "on bloody stumps" even after both of his legs were blown off, encouraging his comrades to come forward. Lummus succumbed to his wounds a few hours later, and he was awarded the Medal of Honor for his sacrifice.

The ultimate sacrifice

As scary as it sounds, many of the men fighting during the horrific Battle of Iwo Jima were experiencing combat for the very time. One of them was PFC James D. LaBelle, a Columbia Heights, Minnesota, native who was just 19 years old. According to Bill D. Ross in "Iwo Jima: Legacy of Valor," LaBelle was a rifleman in the second battalion of the 27th Marines, 5th Division, and had constantly escaped death since first landing at Iwo Jima. That was until March 8, 1945, when LaBelle and a few others found themselves pinned down by heavy fire while near the mouth of a cave. Unable to lodge a counterattack or escape, they were effectively trapped.

While they were sheltering behind a boulder near the cave, a Japanese soldier lobbed a grenade toward them. Sacrificing himself to save his fellow GIs, LaBelle jumped on the grenade to smother the explosion. It worked, shielding his comrades from harm, but proved fatal for LaBelle. For his heroism, the army awarded LaBelle a Medal of Honor, posthumously. Today, LaBelle is buried at Fort Snelling National Cemetery, in his home state of Minnesota.

An armed corpsman

Though they don't often get the same recognition, corpsmen are some of the most important members of the military. Corpsmen are medical specialists who fight in the field with the infantry, except they provide medical treatment instead of shooting guns. Corpsmen are typically unarmed in combat, but that is not always the case. In WWII, one Navy corpsman, PhM1c Francis J. Pierce, became famous for his exploits with a Tommy submachine gun. Joining the U.S. Navy with his parent's permission when he was still 17 following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Pierce first got into action in February 1944, in the Pacific Theater.

On March 15, 1945, at Iwo Jima, Pierce found himself amidst the carnage and destruction, trying to care for the wounded. He used the Tommy gun incredibly effectively to provide support for the wounded, at times risking his life to intentionally draw fire away from wounded men. Later, Pierce himself fell victim to both grenade and rifle fire, but he still maintained his task of caring for other wounded soldiers, putting them above himself for treatment.

After the battle, the U.S. Navy recognized Pierce by giving him the Navy Cross and Silver, two of their highest honors. However, those were later changed to a Medal of Honor in 1948. Pierce survived until December 21, 1986, when he died from cancer.

Protecting K Company

Born on July 10, 1910, in Santiago Atitlán, Mexico, Sgt. Jose Mendoza Lopez would grow up to become one of the greatest American heroes of the Second World War. A member of the U.S. Merchant Marine in his late-20s, Lopez was drafted into the army in 1942. He participated in the D-Day landings in Normandy, France, and later earned a Purple Heart and Bronze Star while fighting in Europe.

During a German breakthrough on December 16, 1945, near Krinkelt, Belgium, Lopez and his machine gun provided valuable support to his fellow soldiers in K Company and the rest of the 23rd Infantry Regiment. He constantly changed positions and single-handedly carried his entire machine gun system, which was exceedingly heavy. Up against a fierce German enemy, at one point Lopez was almost knocked out by a tank blast, but he stayed fighting. Covering K Company's withdrawal, Lopez put his life on the line time and time again in the face of massive enemy resistance. He killed more than 100 soldiers in less than seven hours, a WWII record.

In addition to the Purple Heart and Bronze Star he had already received, Lopez was awarded the Medal of Honor from the United States and the la Condecoración del Mérito Militar from Mexico. Lopez later served during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, finally retiring in 1973. He died from cancer in 2005, and is buried at the Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio, Texas.

A squad leader's dedication

The Battle of the Bulge in Belgium was one of the most arduous and grueling of the entire war. Allied troops battled snow, freezing temperatures, frostbite, and fatigue, as they gritted out six weeks of brutal combat in the Ardennes Forest. One of the young men fighting in the battle was SSG Vernon McGarity from Right, Tennessee. Still grieving the loss of his infant son, McGarity shipped out to boot camp first thing in January 1943. After extensive training, he arrived in Europe late in 1944, making his way to the battlefield that December.

On March 16, 1945, McGarity found himself deployed near the area of Krinklet, Belgium, facing an attack from the German army. Finding himself injured, McGarity refused aid and instead stuck it out on the front lines with his comrades. He started shooting bazookas, taking out snipers, and scrambling to secure ammunition for his fellow GIs, saving countless lives in the process. Unfortunately, the Germans broke through, and McGarity and his squad were taken as prisoners of war (POW). It was not until a month later that he was freed from his POW detention, and he was awarded the Medal of Honor by the president later that year. McGarity also earned a Purple Heart and Bronze Star for his heroics, and he died in 2013 from cancer (via The Washington Post).

A deadly patrol

Even though they did have full civil rights at the time, Black Americans played a pivotal and vastly important role in the Second World War. Of them, one of the most heroic and courageous was SSG Edward A. Carter, who was born in California but spent much of his childhood growing up in Asia with his missionary parents. While attending the Shanghai Military Academy in 1932, the Japanese attacked China in Shanghai, and Carter briefly fought with the Chinese Army against the Japanese.

After his discharge, he entered the U.S. Merchant Marine and later fought in the Spanish Civil War against the Nazis. Having already faced two Axis armies, Carter joined the U.S. Army in late-1941, where he experienced racism from his superiors. Following the integration of combat units in 1944, Carter was stationed near Speyer, Germany as part of the 12 Armored Division. On March 23, 1945, Carter and his squad came under attack from the Germans. Immediately, several of his squad mates were killed and Carter had to quickly find cover.

Despite becoming wounded, Carter managed to kill several Germans and take two as prisoners of war. For his actions, the army awarded Carter the Distinguished Service Cross. However, after it was determined he was denied the Medal of Honor due to his race, he was awarded the medal by Bill Clinton posthumously in 1997. Carter himself passed away in 1963, and he is buried at the Arlington National Cemetery.

'We'll Do It'

A native of San Marcos, Texas, Mexican-American Pvt. Cleto Luna Rodríguez joined the U.S. Army in 1944 when he was still in his early-20s. On February 9, 1945, Rodríguez found himself stationed in Manilla, Philippines, fighting with the 148th Infantry Regiment. While defending a railroad station, Rodríguez and his unit came under heavy fire while initiating an attack against the Japanese forces. Rodríguez ran forward to take the fight to the Japanese, and alongside him was PFC John Reese, a member of the Cherokee Tribe, who helped Rodríguez lay down the covering fire.

Killing more than 80 enemies with machine guns and grenades, Rodríguez and Reese saved countless American lives by drawing the Germans' firing and eliminating them. Facing upwards of 300 enemies, Rodríguez and Reese did not panic but instead laid down steady, and deadly, fire from their Browning automatic rifles. Tragically, Reese was killed by enemy fire during their return to the squad, but Rodríguez survived and fought until the end of the war. As part of the 148th Infantry Regiment, Rodríguez and Reese wore a patch that bore the regiment's motto, "We'll Do It," which they took to heart during the battle.

Both men were awarded the Medal of Honor for their efforts, and Rodríguez continued to serve for the rest of the war. He died in December 1990 and is interred at the Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery in San Antonio, Texas.

George Fleming Davis returns home

When George Fleming Davis found himself stationed in the Philippines towards the end of WWII, unlike most of his comrades, it was actually a homecoming. See, Davis had been born in Manila, Philippines, in 1911 when his father was stationed there as a civilian working with the U.S. Navy. Following in his father's footsteps, Davis soon entered the U.S. Naval Academy and earned his commission in June 1934.

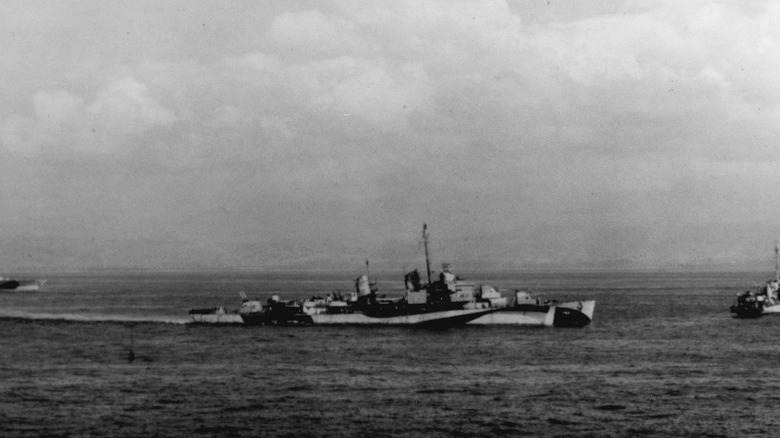

Davis was still in the Navy at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, and he was stationed there when the attack happened, barely surviving as his ship sank. A few years later, in 1944, Davis made his return to the Philippines, this time as the commander of the U.S.S. Walke destroyer. While participating in the Invasion of Lingayen Gulf in January 1945, the Walke was hit by a Japanese kamikaze bomber. The Walke was immediately compromised, and soon a massive gasoline fire ignited on the bridge.

Davis received severe burns from the fire but did not relinquish control until the fire was put out after some time. Tragically, Davis died from his wounds, never making it off the Walke. Davis was awarded the Medal of Honor for his sacrifices, solidifying his reputation as one of the bravest commanders in U.S. Navy history.

Fighting through a broken foot

When the United States entered the Second World War in December 1941, for many soldiers in the National Guard, it meant transitioning immediately to active duty. One of those brave men was 2d. Lt. Ernest Childers, a member of the Muscogee Creek Nation from Broken Arrow, Oklahoma. Childers had joined the guard in 1937, and after his unit transitioned to active duty he was stationed in Italy, in 1943. He participated in the Invasion of Salerno in September, with his unit's objective being the town of Oliveto.

Childers broke his foot after landing, but that did not stop him from getting heavily involved in the combat. He led an attack that took out multiple machine gun nests and riflemen, which had been laying devastating fire on his fellow GIs. He single-handedly killed multiple enemies, including using an ingenious trick to fool some of them. He threw rocks at a squad of Germans near a machine gun nest, making them think they were grenades and causing them to stand up and get eliminated by Childers and his men.

For his actions, Childers was later awarded the Medal of Honor, becoming the first American Indian to receive the honor. Following the attack, Childers continued fighting until becoming wounded at the Battle of Anzio. Childers died in March 2005 in Tulsa, Oklahoma, of natural causes (via the Los Angeles Times).

Fighting for Fish Hook

Not all of the battles for WWII took place overseas, and some of the most intense fighting actually happened on American territory. In June 1942, the Japanese invaded the United States in the Territory of Alaska at the Aleutian Islands. It was not until almost a year later that the U.S. met the attack, finally landing men from the 7th Infantry Division near Attu at Holtz Bay in May 1943.

One of the men of the 7th Infantry was Pvt. Joseph Martinez. Martinez had been drafted into the army the year prior to landing in Alaska, and the fighting he endured there was some of the most intense of the war. On May 26, Martinez and his men tried to attack a pass known as the "Fish Hook" for the second time, but they quickly came under enemy fire and were pinned down. However, rather than lay down and surrender, Martinez started to charge forward and attack the Japanese invaders. Soldiers rallied behind and started to push forward, and soon Martinez started to rain fire down into a Japanese trench.

While firing into the trench Martinez was felled by a bullet, and he died that afternoon. Martinez was honored with the Medal of Honor for his actions, and today there is a statue of him in Denver, Colorado, just a few hours from his hometown of Ault.