The Untold Truth Of The Harlem Globetrotters

The Harlem Globetrotters just might be the greatest show on earth. The touring exhibition team combines top-level basketball skills with unbelievable shots, amazing passes, and choreographed comedy to create one of the most entertaining acts in history. Starting off as a normal (but extremely good) basketball team in the 1920s, the Globetrotters incorporated athletic stunts a couple of decades in, propelling the squad to international acclaim and enduring popularity, performing for millions all over the planet.

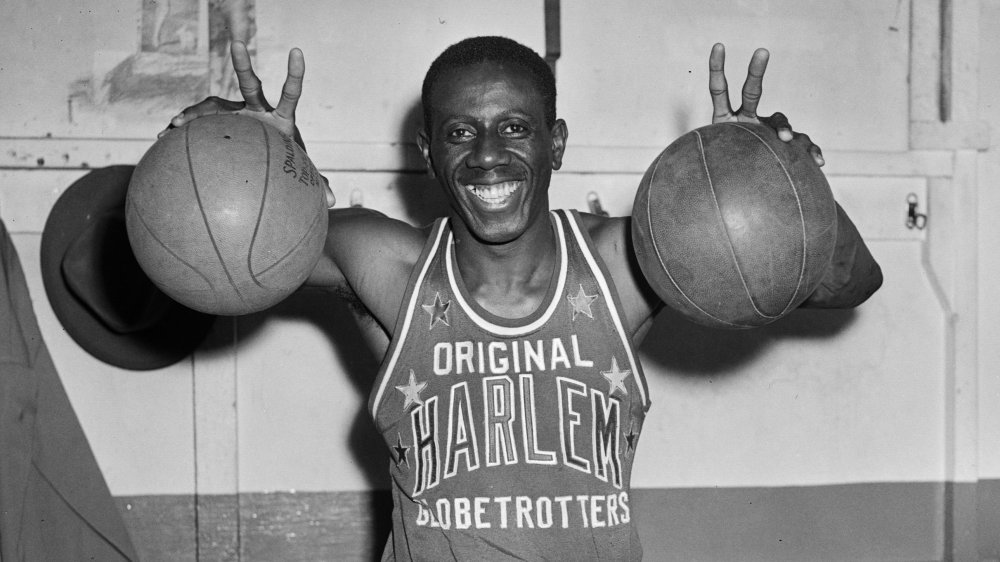

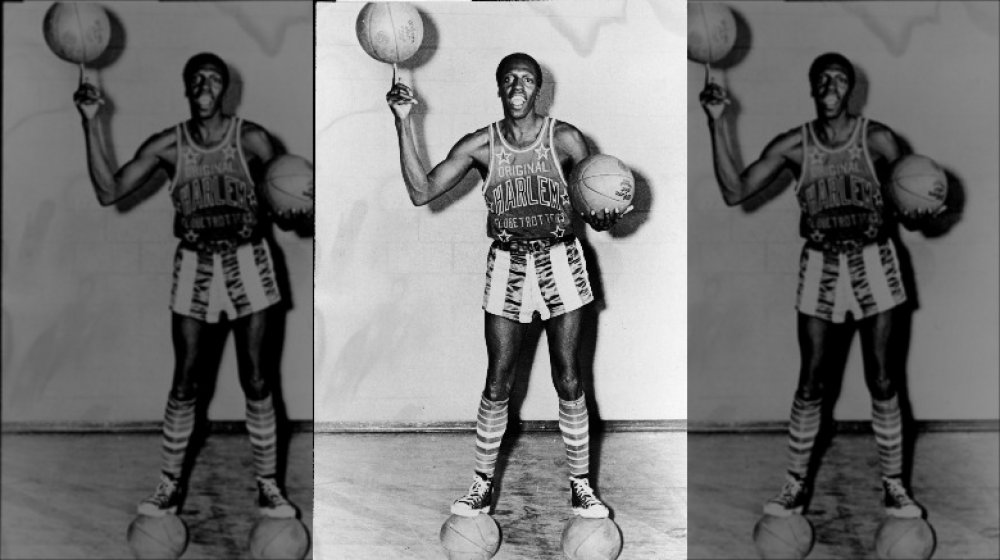

Operating apart from the NBA or other leagues, the Harlem Globetrotters has its own alternate history of pro basketball, with its homegrown superstars and legends becoming household names and pop culture icons over the team's long history, particularly Reece "Goose" Tatum, "Sweet" Lou Dunbar, Fred "Curly" Neal, and Meadowlark Lemon, whose otherworldly basketball skills delighted fans and shamed their patsy team, the Washington Generals, thousands of times. And if you want to know more about the fascinating and untold truth of the squad, here's a look into the rise, dominance, and unique appeal of the Harlem Globetrotters.

The 'Savoy Globetrotters' doesn't have the same ring to it

The team named after a neighborhood in New York City didn't actually originate there. According to the Black Fives Foundation, in the early 1920s, the Eighth Regiment of Chicago team, an African-American squad, played its home games at a Chicago armory. And in 1924, it won the Colored Basketball World's Championship. After the squad was renamed the Giles Post American Legion Five, team manager (and nightclub promoter) Dick Hudson arranged in 1927 for them to play their games at Chicago's newly built Savoy Ballroom. As part of the deal, the team renamed itself the Savoy Big Five. The team took to its new home court in early 1928, where it played and easily defeated numerous college and other non-league, barnstorming teams.

At the end of the season, the Savoy Five split up over money issues, and most of the players (along with manager and coach Hudson) left to form a new team. Chicago basketball fan and businessman Abe Saperstein signed on as both a booking agent and a coach for this new group, and he gave the team the name "New York Globe Trotters" to suggest it hailed from a much bigger city and that it was seasoned and experienced. Saperstein soon dropped the "New York" in favor of "Harlem," embracing the name of the predominantly African-American New York neighborhood. Still, the team wouldn't play in a major city besides Chicago for five years ... and not in Harlem until 1968.

It was once one of the best basketball teams in the world

During its formative years of the late 1920s and 1930s, the Harlem Globe Trotters (later the Globetrotters) remained extremely dominant, beating almost everyone they played. In its first season, the team amassed a record of 101 wins and 16 losses. They'd tour into towns big and small and take on and decisively defeat squads from high schools, colleges, and other barnstorming teams. According to POV, by 1934, the Globetrotters had contested 1,000 games, and by 1939, the team was so good that it could contend for a "world championship" of basketball.

Sadly, the Globetrotters lost that title game to the New York Renaissance (also called the Harlem Rens), but in the 1940 Chicago World Pro Tournament — an invitational festival but a de facto championship — the Globetrotters beat the Rens by one point in the semifinal round and then defeated crosstown rivals the Chicago Bruins by two points to win the whole thing.

The night the Harlem Globetrotters discovered the magic of goofing off

While the Globetrotters kept playing serious basketball into the 1940s, an ugly incident at a game in Woodfibre, British Columbia, in 1939 would lead to the team's future path and, ultimately, wild success. While the players conducted their on-court warm-ups, drunken fans unleashed some racially fueled heckles at the Globetrotters. According to the book Sport: Race, Ethnicity and Identity, point guard Runt Pullins huddled the team together and suggested that the best way to shut up "these wise guys" was to absolutely dominate and embarrass the local team they had to play that night.

And that's what they did, running up the score to a ridiculous 112 to 5. That only angered the crowd more, and to pacify the increasingly raucous and possibly violent fans in the stands, the team calmed them down with basketball tricks. Runt Pullins smiled as he dribbled the ball between his legs, Inman Jackson threw a pass behind his back to Kid Oliver, who tossed up the ball and caught it on his neck, then rolled it down his arm. From that night on, coach Abe Saperstein told players to incorporate the tricks into the games, particularly as it could settle down audiences uncomfortable and hostile to the notion of a dominant team of African-Americans.

The Globetrotters helped desegregate the NBA

Before there was an NBA, there was the BAA (Basketball Association of America). Also different from today's pro basketball world is that the BAA was segregated, meaning the top stop for African-American players was the touring Harlem Globetrotters. But everything started to change on February 19, 1948, when the BAA's all-white Minneapolis Lakers played the Globetrotters in an exhibition game in Chicago.

More than 17,000 basketball fans showed up to watch the showdown between the Globetrotters and the Lakers, with their star rookie George Mikan on the court. Before that day, the Globetrotters had won 102 games in a row, but the Lakers proved formidable, leading 32 to 23 at halftime. Globetrotters coach Abe Saperstein ordered his players to contain Mikan by double-teaming him, an effort that held the center to just nine more points and which resulted in a score tied at 59-59 with 90 seconds remaining. As time ran out, the Globetrotters' Elmer Robinson sank a deep shot, giving his team a 61 to 59 victory. A year later, the Globetrotters would best the all-white Lakers once more.

Beating a major pro squad made African-American players both undeniable and attractive to what were by then NBA owners. As a direct result of those two games, the NBA opened up to non-white athletes. African-Americans Chuck Cooper and Earl Lloyd were both drafted in 1950, while the New York Knicks signed Nat "Sweetwater" Clifton, the Globetrotters' center.

The untold truth of the Washington Generals

By the early 1950s, all the pieces were in place for the modern, familiar iteration of the Harlem Globetrotters — a traveling squad that played real basketball games as a pretense for basketball-themed showboating and entertaining shenanigans. However, there was one problem. The Globetrotters were running out of people who would play them. After all, the Globetrotters are one-of-a-kind in their approach, and in its early decades, they played exhibition games against other teams that were always serious, legitimate basketball squads. As a result, these teams didn't want to lose or deal with the Globetrotters' on-court antics.

The only solution was for the Globetrotters to have a set series of opponents who knew what to expect and to be gracefully defeated night after night while playing the straight man. In 1953, the Globetrotters organization created several opposing teams, among them the Boston Shamrocks, the New Jersey Reds, the New York Nationals, and most famously, the Washington Generals. But this wasn't a small league of assorted teams. All those opponents were one and the same. Each night, the Globetrotters played the same group of players, who'd just alternate their jerseys to give the illusion of variety. The Washington Generals were retired as the Globetrotters' usual opponent in 2015, but then in 2017, the Globetrotters actually bought the opposing team, reigniting their old rivalry.

Sometimes the Harlem Globetrotters lose

While it's essentially the job of the Washington Generals (or whoever) to lose, the opposing players do occasionally win because even the Harlem Globetrotters have to lose once in a very rare while.

Sure, the Generals were defeated by the Globetrotters more than 17,000 times and beat them very rarely. But on a January 5, 1971 game in Martin, Tennessee, the Globetrotters got so caught up in the comedy and stunts that the players didn't realize the New Jersey Reds were keeping the score close. Near the end of the fourth quarter, a legitimate basketball game broke out, and the Globetrotters fought hard for a victory. At the last moment, Red Klotz — the Reds' organizer, player, and coach — nailed a buzzer-beater, giving the team a 100 to 99 victory, ending a 2,495-game losing streak for the players who regularly made up the Globetrotter's opposition.

Beyond that rare loss in a comical game, the Globetrotters have lost dozens of games, primarily to all-star teams, college teams, all-star teams made up of college players, and in 1958, to the NBA's Minneapolis Lakers.

The Harlem Globetrotters made a lot of weird TV shows

It was probably a foregone conclusion that the Harlem Globetrotters would wind up the stars of movies and TV shows. After all, they're more of an entertainment enterprise than a serious sports organization, plus those red, white, and blue uniforms really pop on screen, almost as much as the seemingly impossible trick shots performed by guys with wonderful nicknames.

Not counting the semi-serious 1951 sports drama The Harlem Globetrotters (starring "Pop" Gates, "Babe" Pressley, and "Goose" Tatum as themselves), the squad stormed onto screens with its fun and wacky vibe intact on the 1970-73 CBS Saturday morning cartoon Harlem Globetrotters. Similar to Scooby-Doo and all its clones, this animated series featured a group driving around and getting into adventures. This was a golden age of Globetrotters, and team legends like Meadowlark Lemon and "Curly" Neal voiced their own characters.

In 1974, the Globetrotters made their way back to Saturday mornings with the live-action variety show The Harlem Globetrotters Popcorn Machine, which, like other mid-'70s shows of this style, featured corny comedy sketches and musical performances. Then the famous team returned to animated form once more in the bizarre 1979 cartoon The Super Globetrotters, in which the already superhuman Globetrotters were imbued with special abilities. For example, Curly could transform himself into a basketball, while "Sweet" Lou Dunbar's afro held a bottomless supply of tools and gadgets.

The team pioneered women's professional basketball

Not only were the Harlem Globetrotters a squad where African-American players could play world class ball and earn a paycheck during the era of segregation, but the organization was also responsible for the first inroads to professional basketball for amazing female athletes in the United States. While no NBA team has ever signed a woman to its roster, the Harlem Globetrotters did in 1985, 11 years before the WNBA was founded.

After captaining the U.S. women's basketball team to a gold medal in the 1984 Summer Olympics, Lynette Woodward fulfilled a childhood dream and suited up for the Globetrotters, the first woman in the team's history. When Woodward left after two years, the team added University of New Orleans star Sandra Hodge and Louisiana State standout Joyce Walker. Both earned a salary of about $75,000 a year, more than the WNBA league minimum a decade later. Proving that hiring women was never a gimmick, the Globetrotters routinely sought out female players. In 2017, Briana "Hoops" Green became the fifteenth female Globetrotter overall.

Popes can also be Globetrotters

The Harlem Globetrotters are among the most universally loved people in the world. What's not to love about a group that spreads basketball, comedy, and pure joy to every corner of the Earth? But while it's certainly an honor to play for the Globetrotters, not everybody can play for the Globetrotters. Still, the organization wants to recognize those who've made a huge impact on their own, non-basketball fields, so it started making major public figures "honorary" Globetrotters in the 1970s. It's sort of like an honorary doctorate bestowed on a famous person who speaks at a college graduation ceremony — it's purely symbolic.

The first non-playing Globetrotter in this capacity was Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, followed by entertainers Bob Hope and Whoopi Goldberg, freedom fighter Nelson Mandela, politician Jesse Jackson, and track-and-field star Jackie Joyner-Kersee. Of course, the only honorary Globetrotter who could probably hold his own in a game is NBA legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. He'd at least do better than fellow honorary Globetrotters Pope John Paul II and Pope Francis. The most recent inductee into this rarified club was Good Morning America host Robin Roberts in 2015.

Some major sports stars have played for the team

While Globetrotter Nat "Sweetwater" Clifton became a notable NBA veteran — not only was he among the first African-Americans in the league, but he played ten seasons, including one all-star selection — several other renowned athletes have put in some time as a Harlem Globetrotter.

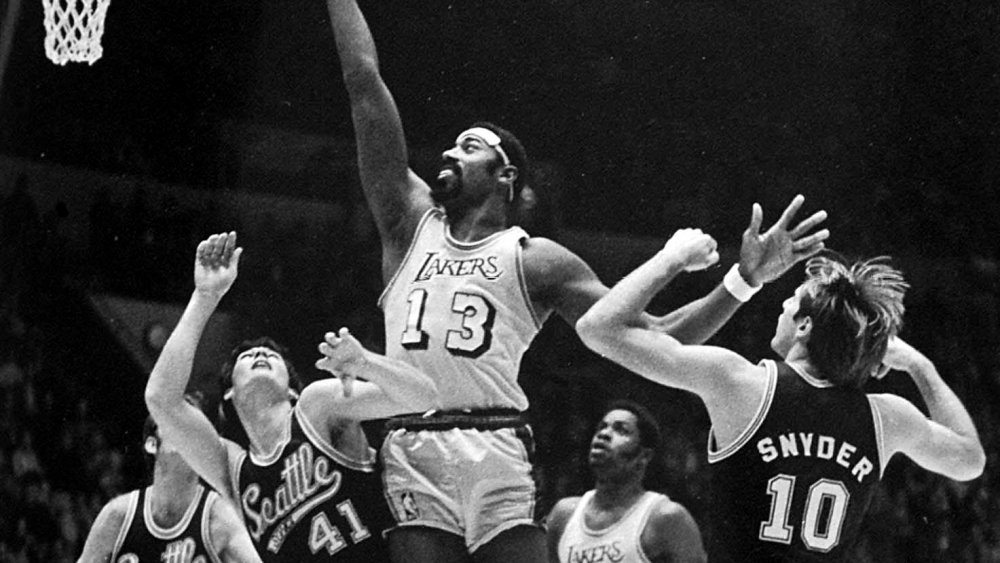

For example, Wilt Chamberlain, one of the greatest basketball players of all time — he averaged more than 30 points a game for nine straight seasons, was named the NBA's Most Valuable Player four times, and scored a record 100 points in one game, to name but a few achievements — spent the 1958-59 season with the Globetrotters after he left college one year early to pro but was denied admittance to the NBA. Connie Hawkins, a five-time all-star, 1968 NBA MVP and Naismith Memorial Hall of Famer also played for the Globetrotters before his pro career began in earnest.

And not only basketball players spent time with the legendary squad. Baseball Hall of Famer Ernie Banks moonlighted for the team while also enlisted in the Army. And before he became a big league pitcher, Bob Gibson turned pro basketball player with the Globetrotters. "I thought Bob was a better basketball player than a baseball player," legendary Globetrotter Meadowlark Lemon told the World-Herald (via White and Blue Review).

The Harlem Globetrotters gave the world its basketball theme song

There's a certain jaunty, whistling-driven song closely associated with basketball. Generally presented as an instrumental, without lyrics, that song is called "Sweet Georgia Brown." And the reason why it makes so many people think of basketball is because it's the theme song of the Harlem Globetrotters, and it's been playing on arena P.A. systems since the 1950s as the team goofs off, practices, and gets the crowd in the mood for a show.

"Sweet Georgia Brown" is actually an old jazz standard that predates even the earliest version of the Harlem Globetrotters. It was written in 1925 and first recorded that same year by Ben Bernie and His Hotel Roosevelt Orchestra. It's since been recorded dozens of times by legends like Ella Fitzgerald, Django Reinhardt, Louis Armstrong, and Bing Crosby. In fact, in one of their earliest recordings, the Beatles even covered the song when they were backing up singer Tony Sheridan. Of course, the version the Globetrotters use was recorded in 1949 by an act called Brother Bones and His Shadows, and it's obviously one of the most famous whistling tunes of all time. However, the song actually does have lyrics ... and it's about a prostitute.

The Harlem Globetrotters have employed all kinds of players

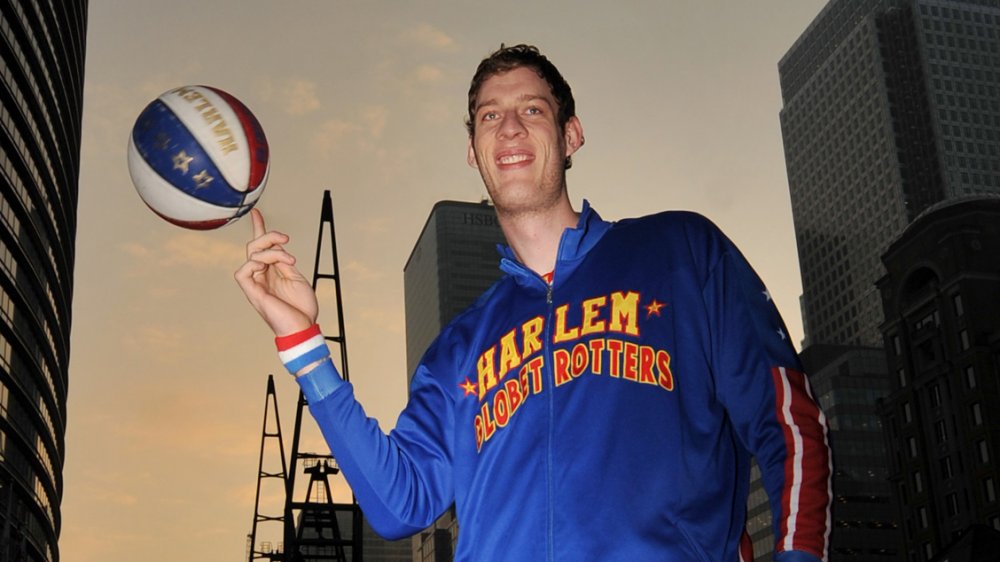

The Harlem Globetrotters will give anyone a shot who can play high-quality, eye-popping basketball, no matter their physical specs. For example, at 7'8", Globetrotter Paul Sturgess (who goes by the ironic nickname of "Tiny") is taller than Manute Bol and Gheorghe Muresan, who both played for the NBA at a listed height of 7'7". And Sturgess also has a Globetrotter-worthy feat. He's so tall that he's reportedly the only pro basketball player in the world who can dunk on a regulation rim without jumping.

On the other end of the NBA height spectrum, there's Muggsy Bogues, who at 5'3" is the shortest player to ever suit up in an NBA game. He's far taller, however, than the shortest-ever Harlem Globetrotter, Jahmani "Hot Shot" Swanson. He stands 4'5" tall. Swanson proves that you don't have to be tall to play pro basketball, while 1940s era Globetrotter Boid Buie showed that you don't even have to have all of your limbs. He joined the squad after playing Tennessee State, averaging double-digits in points for the Globetrotters throughout his tenure, which is especially impressive because he'd lost his left arm in a car accident about a decade earlier.