Freaky Sea Monsters That Have Resurfaced After Millions Of Years

"Hic sunt dracones," say the warnings on ancient sea maps — "Here be dragons." Fictitious as tales of that warning might be, its meaning is clear: "We don't know what's out there, so take care." Such advice would have carried immense, if obvious, weight in an uncharted world full of far more mystery than our modern, GPS-mapped globe. But sometimes, human imagination and paleontological reality align, and sea monsters turn out to be real, even if it takes tens or even hundreds of millions of years to find out.

But the word "monster" is a tricky one. We're not talking about cryptids in this article, like the ever-elusive Loch Ness Monster in Scotland. We're talking mostly about fossilized reptiles from the Mesozoic Era (about 252 million to 66 million years ago) that call to mind stories of ocean-prowling fiends. Sometimes, such stories are mere plot inventions, like the twin-threat Scylla and Charybdis from Homer's "Odyssey." Other stories about sea monsters sound believable but turn out to be nothing more threatening than a simple turtle, like in an account from 1959 off the coast of Scotland. Yet other monstrous creatures were some of the most dangerous sea creatures to ever live, like the 70-foot-long megalodon shark.

Judging by how many new fossils keep surfacing after millions of years, it's safe to say that there's probably a lot more big, scary predators of the past waiting to be discovered. Many of them might be long-necked plesiosaurs, like the recently announced Traskasaura sandrae or Plesionectes longicollum. Or, they might be crocodile-like pliosaurs or dolphin-like ichthyosaurs. But in all cases, it's definitely safer for sailors and landlubbers alike that such creatures no longer exist.

Traskasaura sandrae: lots of big, chomping teeth

If a sailor from yesteryear ever came across Traskasaura sandrae on the high seas, he'd probably say he saw a monster. Actually, it'd just kill him. That's because Traskasaura was basically an entire snake writhing from the body of a shell-less turtle, lashing out with rows of misaligned, blade-like teeth meant for chomping and crushing. Let's be glad that it's among those prehistoric predators that went extinct, because it'd be game over for any hairless ape who swam in its vicinity.

But interestingly, it took some of those hairless apes quite awhile to figure out exactly what Traskasaura was. Discovered back in 1988 along the Puntledge River in eastern Vancouver Island, it had a 39-foot-long body and thin, bendy neck with at least 50 vertebrae. Dating to about 85 million years ago during the final of three dinosaur eras, the Cretaceous Period (145 to 66 million years ago), it had a strange combination of new and time-tested evolutionary traits. For instance, it plunged downwards to snatch prey, likely ammonites, a type of shelled mollusk, and would have had no trouble just crushing their shells and swallowing.

Investigations and research into this odd, giant water predator only resolved in 2023. That's when researchers decided that it was not only a new species of elasmosaur — a type of plesiosaur — but its own genus. That's when it got its name, "Traskasaura sandrae," with the first word of its binomial nomenclature — Traskasaura — indicating its unique genus, or group. Currently, Traskasaura's skeleton hangs from the ceiling at the Courtenay and District Museum and Paleontology Center on Vancouver Island.

Plesionectes longicollum: like Loch Ness, but real

Next up, we've got another dinosaur in the plesiosaur group. This means fins for swimming and a really long neck with a bunch of sharp teeth at the end scouring for hapless oceanic prey. And just like Traskasaura sandrae, our current creature was discovered decades ago and only got its name recently: Plesionectes longicollum.

You could think of Plesionectes longicollum as a smaller, less scary (but still deadly), and older version of Traskasaura. Plesionectes longicollum — "long-necked near-swimmer" — was quarried in Holzmaden, Germany, in 1978 in the fossil-filled Posidonia Shale fossil beds. It was so well intact that some of its flesh got fossilized along with its bone. But, the fossil was so different from its peers that it couldn't receive proper attention and get classified until 2025. Now, it stands as a one-of-a-kind example of a species, aka, a holotype.

By the numbers, Plesionectes longicollum was about 10.5 feet along and had a 4-foot, 43-vertebrae neck that approached half the length of its body. But, the specimen wasn't fully grown, so final size could have been bigger. Also, Plesionectes longicollum dates back to about 183 million years ago during the Jurassic Period (201 to 145 million years ago). To try and put that in perspective, that's over twice as old as Traskasaura sandrae, which dates to 85 million years ago. Humans only started domesticating plants 12,000 years ago.

Sadly, Plesionectes longicollum doesn't seem to be on display. As far as we know, it's still being held in storage in the Stuttgart State Museum of Natural History in Stuttgart, Germany, the same place it's been since it was discovered.

Ophiojura exbodi: eldritch horror embodied

We might as well mix things up by steering away from the long-necked Loch Ness-type creatures and toward Cthuloid horrors, which are honestly way creepier because they look so much more alien. We don't mean cephalopods in this case (squids, octopuses, etc.), nor do we mean squid-headed humanoids (thankfully). But we do mean lots of tentacles and eight hook-fanged mouths. Enter Ophiojura exbodi, the thing that you never knew would be your worst nightmare fuel. The creature's stats tell its disturbing story: eight long, hooked, mucus-exuding tentacle arms extending from a central hub body; eight individual, circular jaws ringed in hooked teeth to shred prey like cheese; multiple, microscopic nostril-like holes on the arms from which spines emerge to help Ophiojura move. Fantastic.

Ophiojura is actually a relative of the modern-day brittle star, similar to the starfish but with spindlier arms and removed by about 180 million years of evolution. Brittle stars crawl on the ocean floor and reach for prey with their arms, living at depths of about 650 feet to about 3,300 feet. And indeed, this is exactly where Ophiojura exbodi was, about 1,600 feet below the ocean's surface east of New Caledonia, which is east of Australia in the Pacific Ocean. Ophiojura's only less-than-terrifying feature is that its arms were pretty short, at about 4 inches each. Thankfully, it doesn't quite reach facehugger levels of terror from the "Alien" franchise.

Researchers found Ophiojura back in 2011, but unlike the two plesiosaurs we covered so far, it didn't have to wait multiple decades to be understood. It's very technical research paper got published in 2021 on The Royal Society Publishing.

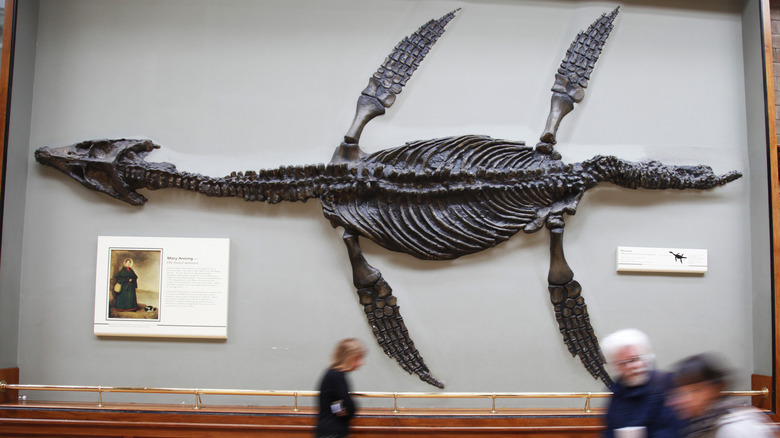

The Pliosaur: the T-Rex of the seas

Next we come to a celebrity among the millions-of-years-old sea monster crowd: the pliosaur, the T-rex of the seas, or Sea Rex. The pliosaur re-entered the public conversation back in 2023 when researchers discovered the most well-preserved pliosaur skull to date. This was such a big deal that a celebrity of a different type, English biologist Sir David Attenborough, did a whole pliosaur documentary on BBC One in 2024. Called "Attenborough and the Giant Sea Monster," it featured some reptile-to-boat size comparisons to help convey the pliosaur's immensity, plus Attenborough calling the creature the "ultimate marine predator," as a clip on YouTube shows.

It's not hard to see why Attenborough gave the pliosaur that epithet, or why the dinosaur is referred to as Sea Rex. Its skull alone is over 6 feet long and each of its 130 teeth is about as long as a human palm. It prowled the oceans around 150 million years ago toward the late Jurassic Period, crushing prey with a bite strength equaling 33,000 newtons. In comparison, a modern crocodile's bite strength equals 16,000 newtons, while a dog's reaches 1,000 newtons. It also had a longish neck, but nothing like the serpentine necks of the plesiosaurs we covered above.

The 2023-discovered pliosaur skull was sticking out of the beach on England's World Heritage Jurassic Coast along the country's southern shores. The coast contains loads of fossils and rock formations covering the last 185 million years of Earth's history, and has played a crucial role in the work of paleontologists and geologists for centuries, going back to natural historian Robert Plot in 1677 and including the work of famed amateur naturalist Mary Anning.

Ichthyotitan severensis: the biggest predator of its time

In contrast to the freakishly long necks and snake-like heads of plesiosaurs, or the burly pliosaur, ichthyosaurs had long, thin mouths like stork beaks. Basically, they were giant murder dolphins. They even inhaled air from the surface of the water like a dolphin, and had huge, dinner-plate eyes to help them find and snatch fish in mouths lined with razor-sharp teeth. So, how we do feel about an 80-foot-long version of this underwater killer? For comparison, modern-day blue whales reach 100 feet long. That makes Ichthyotitan severensis — note the word "titan" in the genus — the biggest ichthyosaur of them all. It lived around 201 million years ago at the end of the Triassic Period (252 to 201 million years ago).

Much like Mary Anning, whom we mentioned earlier, we have amateurs to thank for finding Ichthyotitan. Father-daughter fossil-hunting duo Justin and Ruby Reynolds came across it in Somerset, England, in 2020. They didn't find an entire skeleton, mind you — just part of a jawbone in better condition than a previously discovered jawbone fragment belonging to the same species. It was in such good condition that researcher Dean Lomax, in charge of the previous 2018 discovery, could now definitively state that they'd uncovered a new, enormous ichthyosaur. Lomax and his team published a paper on the whole thing in 2024 on PLOS ONE, thus revealing Ichthyotitan severensis to the world.

Research is still ongoing into Ichthyotitan. But, one fact stands out: Like our pristine pliosaur skull, Ichthyotitan had a 6-foot-long jaw. That's definitely big enough to swallow lots of people whole and to conjure tales of sea monsters — if anyone had been around to see one, that is.