What Johnny Cash's Folsom Prison Concert Was Really Like

In 1968, Johnny Cash went to prison, and one of the toughest facilities in the nation at the time to boot: Folsom State Prison in California. But while Cash had a dark side everyone liked to ignore, he wasn't heading into the imposing institution after being convicted of serious crimes. No, he was there to pay a visit to benefit the inmates. Over the course of one day, the rogue country superstar played a collection of his best-known hits — and one brand new song — to the general population of the prison and recorded it all for a live album: "At Folsom Prison."

Needless to say, the inmates got to witness one of the most compelling and vital live albums as it unfolded in real time. It was also a high point for Cash — it revitalized his career after a long slump, reminding the world that he was an electrifying performer who was also in touch with the people his songs were about: Those who dwell on society's fringes. Here's what it was like at Folsom Prison when Johnny Cash, the man who always wore black, generated a bit of light by recording "At Folsom Prison," and how it shaped history.

At Folsom Prison was staged out of desperation

In the 1960s, Johnny Cash was at a low point in both his professional and personal life. Dealing with a persistent substance use issue made the musician unreliable. At that time, he often missed scheduled concert dates, and if he did make it to the venue, his performances were often of less than stellar quality because of Cash's obvious intoxication. That apparently led to some audience behavior that Cash didn't enjoy, which made him amenable to the idea of playing a show behind bars. "One thing he liked about playing prisons: If he did something the audience didn't like, they couldn't leave," Cash's drummer, W.S. "Fluke" Holland, told NPR.

Also, Cash had gone a couple of years without a big hit. Once a dominant and prolific presence on the country chart, Cash released fewer singles in the late-1960s relative to his previous output. "We couldn't get him in the studio," Cash's bassist, Marshall Grant, told

. "And when we got him in the studio, he'd come completely unprepared. He came in and would start writing songs. You can't do that because every part of our career proves, especially with us and with him, you had to get the songs, work it up, have it ready to go. Well, we couldn't get him to do that." In order to get something — anything — on tape for public consumption, Cash's band floated the idea of recording a live album at Folsom Prison in California.

The concert was a real-life take on a fictional Johnny Cash song

Johnny Cash and his band were already scheduled to play a show at Folsom State Prison in California in January 1968. "I mean we're going to Folsom, and we're doing a show there to entertain the prisoners because they can't get out to be entertained," W.S. "Fluke" Holland told Rolling Stone. "It was like we just were doing a nice gesture." According to Holland, he didn't think the record would resonate with the public. "It won't sell enough to pay for tape. I remember saying that two or three times," he recalled. "In fact, I remember saying it to Bob Johnston, who produced the thing."

It was something of a foregone conclusion for Cash to bring his live show to Folsom Prison: Back in 1955, he scored one of his earliest top-five country chart hits with "Folsom Prison Blues." Told in the first person, it's the story of a man incarcerated at Folsom, lamenting his situation and expressing his regrets and desire for freedom whenever he hears a passing train's whistle. ("Folsom Prison Blues" also includes the famous and immortal Cash lyric, "I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die.") Cash had been inspired to pen the song after watching the documentary "Inside the Walls of Folsom Prison" in the early 1950s; he'd never been incarcerated himself.

He and his band were essentially imprisoned at Folsom

When Johnny Cash and his small band of musicians arrived at Folsom State Prison, situated in the town of Represa in Northern California, they were immediately and profoundly moved by the bleakness of the situation. But then, that's kind of why they'd agreed to play a show there — two on the same day, actually. "I think John believed he was just making the public more aware of the conditions in the prisons," famous music photographer Jim Marshall told Rolling Stone. "I think he saw himself as an entertainer who could make a difference in their lives even for an hour," he added. Marshall Grant described the facility as "so quiet and so desolate," saying its atmosphere was "somber" and "unlike any place you've ever been in your entire life."

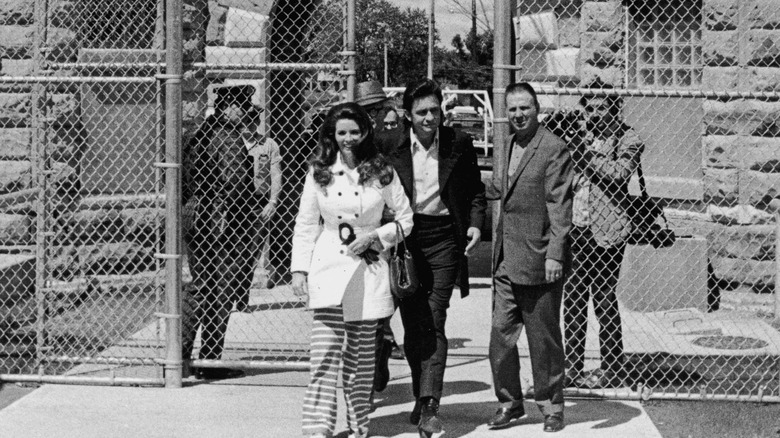

Then they got to experience a taste of prison standard operating procedure. After leaving their motel, Cash and crew were taken to the facility in a secure prison bus. They were allowed out once they had passed through granite walls and two sets of metal gates. "Everybody is watched, including us," Grant recalled. "We were the prisoners in these prisons. So that sort of made it uncomfortable. It didn't mean that the prison guards weren't nice about it, but they had rules and regulations that we had to abide by, and we weren't going to break those rules."

His entourage did illegal stuff at Folsom

That's not to say that some members of Johnny Cash's party didn't violate the rules of Folsom State Prison — or the law in general. "Only a year before, I was arrested for shooting somebody," photographer Jim Marshall revealed to Rolling Stone. "I could have been in there. In fact, I was on probation when we went to Folsom." He also very much broke the law while at the correctional facility, although he claimed it was accidental. "I had a couple of little balls of hash in my camera bag that I'd forgot about, and they didn't find it, obviously," Marshall recalled. "But can you imagine going into a prison with some drugs on you?" With that said, he cameraman was stopped by guards for sort of breaking one rule: He wore jeans to the gig, and those would've made him look like a prisoner, who wore jeans at the time. Someone had to quickly find a pair of brown pants for Marshall to wear.

Marshall Grant also inadvertently broke the rules, but luckily, he addressed the matter quickly. "I carried this gun into Folsom, which was a real gun that we used as part of a gag on stage," he explained. "You pulled the trigger and it would smoke. ... Well, I carried it in my bass case. I didn't think anything about it." When he discovered it when preparing to take the stage, he nervously approached a guard and surrendered the prop/weapon.

Johnny Cash wasn't the only performer at Folsom Prison

There was one big reason why Johnny Cash played two concerts at Folsom Prison: contingency. As the shows were being recorded for posterity (what would eventually be released as "At Folsom Prison"), the second concert essentially provided alternate takes in case the first set's performances failed in any way. Ultimately, all but two songs on the LP were recorded in the first concert.

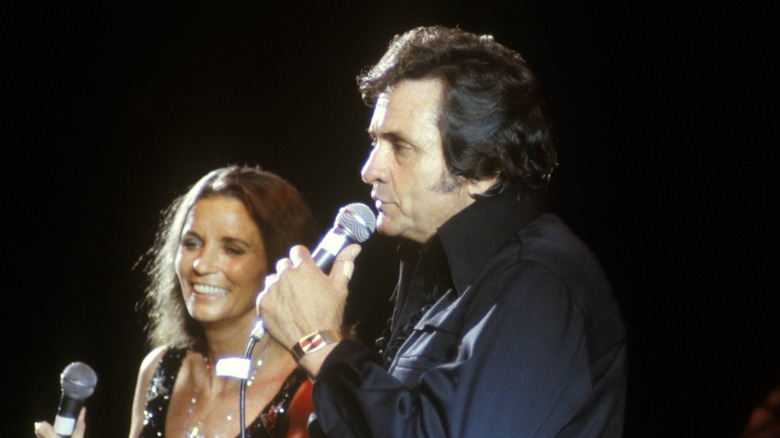

"At Folsom Prison" was a heavily edited album — it doesn't provide a full account of what the Folsom Prison concerts were really like. More than 3 million people bought the record, many of them having no idea that there were other acts on the bill that preceded Cash. First to take the stage was early rock n' roll star and onetime member of Cash's band, Carl Perkins, who played his signature song, "Blue Suede Shoes." Then the Statler Brothers vocal group went on, singing "Flowers on the Wall" and "This Old House." Only then did Cash come on to do his show, joined on a couple of numbers by his future spouse, June Carter. "We felt it wasn't the place to take the entire family," Marshall Grant told Rolling Stone. "But John wanted June, and we felt that we could look out after her ourselves, along with the prison guards. One female is easy to look out after where four or five women could have been a problem, and that's the reason the Carters weren't on it."

The show didn't have top-notch production values

It's no surprise that Folsom State Prison, at the time a maximum-security prison, wasn't really set up to handle an entertainment show from one of the nation's foremost musical acts. "That was the days when we didn't have monitors on the stage ... All they had was this house system," Johnny Cash's drummer Fluke Holland told Rolling Stone. In fact, the sound quality was so poor that the backing musicians struggled to figure out what was going on. "And when [we] got through with the song and went to the next song that John would start to do, we had no idea what it was going to be," Holland recalled. "So he'd start singing the song, and we couldn't hear. We'd just start playing something. We didn't know if we was doing the right thing or whatever, but everything worked out really good."

Those shows were the first-ever live recording of a prison concert, and as such, the production crew needed some help from the audience. Los Angeles disc jockey Hugh Cherry was called in to emcee the event, and he explained to the crowd of prisoners exactly how he wanted them to behave. Most importantly, they were instructed to remain silent when Cash walked up to the microphone and then to go wild when the singer said, "Hello, I'm Johnny Cash." The reason? It would sound good on the record.

A Folsom prisoner wrote one of the songs Cash performed

Johnny Cash opened his Folsom Prison concerts with "Folsom Prison Blues," and it wasn't the only song about Folsom he played that day. He finished off both sets with "Greystone Chapel," a stark and poetic tune about finding spiritual comfort while serving time at the prison. "This next song was written by a man right here in Folsom Prison, and last night was the first time I've ever sung this song," Cash said from the stage (according to "The California Report"). "Anyway, this song was written by our friend Glen Sherley." A surprised Sherley looked up in wonder from the front row.

Sherley, serving a life sentence for armed robbery, was persuaded by the prison's DJ to write a song emulating Cash. The DJ passed a recording of Sherley's "Greystone Chapel" to the prison's chaplain, Floyd Gressett, who was friends with Cash, a parishioner at his church in Ventura, California. When the musician was rehearsing in his Sacramento hotel room the night before the Folsom concerts, Gressett gave Cash the tape, and he and his band learned it immediately.

Cash befriended Sherley, and with the aid of some friends — Rev. Billy Graham and Gov. Ronald Reagan — he got the prisoner transferred to a minimum security facility. Paroled in 1971, Sherley recorded an album after Cash helped him secure a record deal. Sherley was also hired into Cash's touring band, though he was fired after he relapsed into substance abuse and tried to fight a fellow musician. He died by suicide in 1978.

Folsom helped make Johnny Cash a prison reform advocate

The concerts at Folsom are only the most famous prison shows that Johnny Cash staged because they were immortalized as a bestselling and acclaimed live album. One of the first times that he played to a literally captive audience was as one of many booked acts for a seven-hour entertainment revue at San Quentin on January 1, 1958. Cash went on to perform for incarcerated fans a lot — at least 30 times over the span of his decades-long career. Just about a year after his performances at Folsom State Prison, Cash recorded another live album at a correctional institute, and one with which he was familiar: "At San Quentin" hit stores in 1969. One of the last major prison shows Cash embarked on was mounted at the Correctional Training Facility in Soledad, California, in 1980.

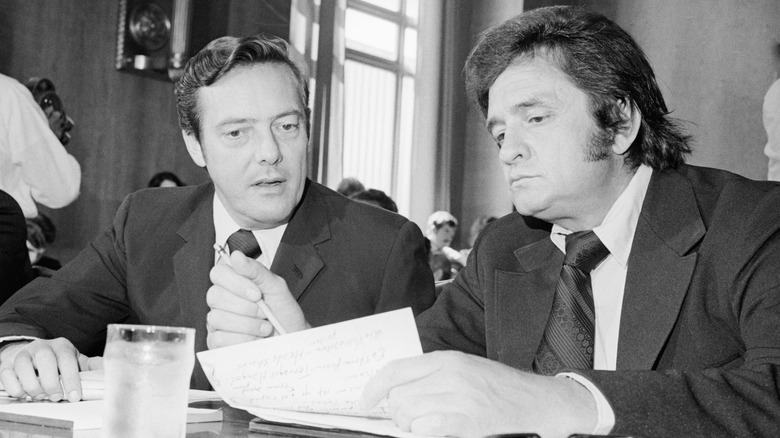

By then, Cash had expended an enormous amount of effort and energy on raising awareness of prisoners' plights and advocating for prison reform. "I have seen and heard of things at some of the concerts that would chill the blood of the average citizen," Cash told the U.S. Senate's Subcommittee on National Penitentiaries in 1972 (via the Library of Congress). "But I think possibly the blood of the average citizen needs to be chilled in order for public apathy and conviction to come about because right now we have 1972 problems and 1872 jails. ... People have got to care in order for prison reform to come about."

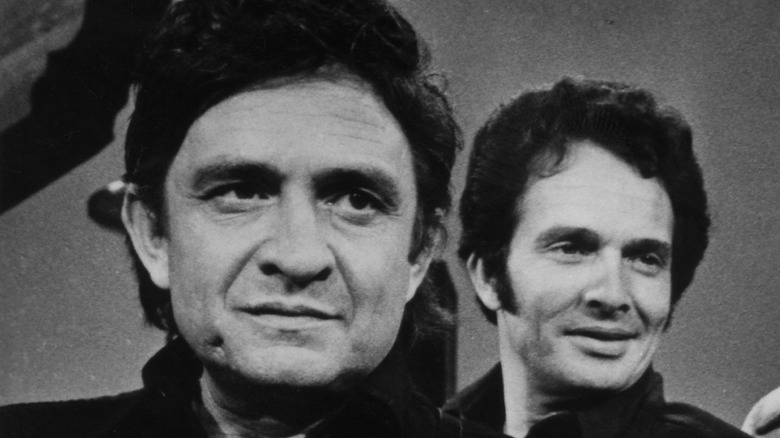

Johnny Cash's prison outreach inspired Merle Haggard

One of the original bad boys of the outlaw country movement, Merle Haggard (above right) really did have a lot of trouble staying on the right side of the law at one point. Responsible for a long string of country classics like "Okie From Muskogee" and "The Bottle Let Me Down," Haggard had a lengthy rap sheet. After spending nine months in Ventura County Jail in California for stealing a car, he tried to rob a Bakersfield restaurant in 1957. Haggard was caught, escaped the city jail, and after he was recaptured, he was sentenced to up to 15 years at California's San Quentin State Prison, though he was released after three for good behavior.

That coincided with some of Johnny Cash's earliest prison concerts, and he played San Quentin on January 1, 1958 (though the date is debated — some say 1959). Haggard remembered Cash, having lost his singing and speaking voice after partying the night before, and he won over the crowd of 5,000 inmates by imitating a gum-chewing guard. Even if the concert wasn't as good as it could've been, it still got a number of prisoners interested in music. "When Cash left, there was guys all over that yard with guitars," Haggard told AXS TV. One of those people was Haggard. "I was the teacher," he recalled. "They all knew that I played." After he showed a younger inmate how to play the intro to a Cash song — "Folsom Prison Blues" — he became a beloved inmate and was on his way to pursue music upon his release.

The state of prison concerts in the 21st century

Johnny Cash's concerts at places like Folsom State Prison in 1968 show the joyful effect that music can have on people, up to and including the incarcerated. What looked like a social movement that could involve many acts was ultimately and mostly a small period in Cash's career. More than 50 years after the recording of "At Folsom Prison" and "At San Quentin," major acts of Cash's caliber don't often play shows at correctional facilities anymore, though it does happen — Queens of the Stone Age performed at San Quentin in 2018 and even ended the set with a Cash cover to tribute the late country legend.

There are, however, multiple organizations and musicians looking to use the power of music and art to improve the lives of prison inmates and aid in rehabilitation and limit recidivism upon parole. In 2018, the Oregon indie band Luther's Boots set out on a tour of state prisons, and its set was full of Cash covers from "At Folsom Prison." Folsom's state of California is one of many that grant prisoners access to tablet computers, which can be used to listen to music streaming services. Elsewhere, ROC City Concerts is based in New York State and stages classical music concerts at jails and prisons.

How Folsom Prison has and hasn't changed since the arrival of Johnny Cash

Some notorious prisons became non-stop party venues, and doing time in a few prisons is practically a death sentence. The day-to-day existence at Folsom Prison is somewhere in the middle. It remains a harsh place, akin to how Johnny Cash imagined it to be when he wrote "Folsom Prison Blues" and what he saw after he experienced it firsthand during his 1968 concert.

Folsom is an aging and decaying facility — California's second-oldest prison, opening in 1880 to help ease crowding at San Quentin State Prison — and overstuffed. The share of people in California in state prisons has about doubled since 1968, and Folsom proves those figures: It's home to about 2,700 inmates, or 109% of its capacity, compared to the approximately 2,000 that attended Cash's show in 1968. With that said, Folsom isn't as severe of a house of punishment as it once was. Built as one of the earliest maximum-security prisons in the United States, Folsom State Prison has been converted into a medium-security institution with a minimum-security wing.

If you or anyone you know needs help with addiction issues, help is available. Visit the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website or contact SAMHSA's National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357).

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org.