What Happened To The Survivors Of Hiroshima And Nagasaki

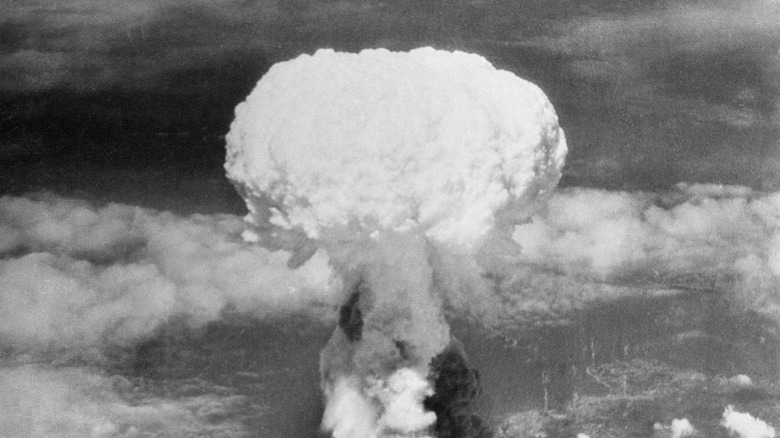

No matter how bad you already think they were, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were worse than you thought. According to Japanese citizens, the true impact of the atomic bombs was pretty much unbelievable, not just the horrible destruction wrought on August 6 and August 9, 1945, at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, but in the years and decades after.

While the nuclear blasts killed hundreds of thousands of people, there were many survivors, even some who were extremely close to the epicenters of the bombings. While after the attack, some victims chose to keep their status as "hibakusha" ("bombing survivors") secret due to rampant discrimination against them — and even against their children — in Japan, others have made their stories public and become involved in the fight for a world without nuclear weapons.

From Nobel Prizes to athletic greatness, here's what happened to the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Issey Miyake

Issey Miyake was 7 years old when Hiroshima was bombed. Decades later, he still remembered all the horrible things he saw that day. His mother died of the effects of radiation three years after the bombing. And Hiroshima would not be the only major world event Miyake was front and center for. As he told author Kazuko Koike for his book, "Where Did Issey Come From?" (via The New York Times), "I seem to be present at occasions of great social change. Paris in May '68, Beijing at Tiananmen, New York on 9/11. Like a witness to history."

Miyake went on to become a successful fashion designer, best known in the U.S. for designing the black mock turtlenecks loved by Steve Jobs. Jobs told his biographer Walter Isaacson, "I asked Issey to make me some of his black turtlenecks that I liked, and he made me like a hundred of them. ... I have enough to last for the rest of my life."

One thing Miyake didn't do was talk about his experience at Hiroshima. It was only when President Barack Obama called for denuclearization in 2009 that the designer decided to speak out in support of the goal. In an op-ed for The New York Times, Miyake explained, "I have never chosen to share my memories or thoughts of that day. ... I did not want to be labeled 'the designer who survived the atomic bomb,' and therefore I have always avoided questions about Hiroshima." Miyake died of liver cancer in 2022, aged 84.

Osamu Shimomura

Osamu Shimomura was 16 years old when Nagasaki was bombed. He was at work in a factory repairing plane engines, as students had been mobilized for the war effort. Once the conflict was over, however, he was eager to continue his education. Introducing Shimomura at Boston University in 2009, University President Robert A. Brown said, "It would not be a stretch to imagine that a teenager from Nagasaki or Hiroshima might reject science because of its role in the Manhattan Project. We are fortunate that Dr. Shimomura did not succumb to such thoughts."

This did not mean, however, that he was particularly interested in the subject. The devastation after the bombings meant educational opportunities were limited in Nagasaki, and Shimomura did not have a proper high school education because of the mobilization. He finally managed to get a place at the only university nearby, Nagasaki Pharmacy College. "I didn't have any interest in pharmacy," Shimomura explained. "It was the only way that I could have some education." This serendipity would continue throughout his time as a graduate student and into his early career by taking opportunities offered to him, sometimes by complete strangers, even if they were unrelated to his studies.

Eventually, this led him to extract and isolate the green fluorescent protein (GFP) from jellyfish, which other scientists used to make breakthroughs in cancer research and many other areas. In 2008, Shimomura was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his work on GFP. He died in 2018 at 90 years old.

Sadako Sasaki

Sadako Sasaki was just 2 years old when Hiroshima was bombed. While she survived the initial blast, the effects of the radiation would eventually kill her. A decade later, Sasaki was diagnosed with leukemia and was hospitalized. While there, she learned the tradition that anyone who folds 1,000 origami cranes will have their dearest wish granted. "From then on, Sadako folded cranes constantly," her father, Shigeo Sasaki, remembered (via the Children's Peace Memorial). "Her wish was to leave the hospital as soon as possible in order to enter junior high school. ... Her wish was so urgent that she endured the pain of her illness and devoted herself to folding cranes."

Sasaki became famous after her death for her attempt (sources disagree on how many cranes she made and if she reached her goal). There are multiple monuments to her, including in Seattle (pictured) and Hiroshima.

Her hope and resilience inspired many others, including her older brother, Masahiro, who wrote an account about her short life. He said, "Innocent children were sacrificed in the war started by adults. Until nuclear weapons are abolished from the world, I will never give up and will continue to tell her story."

Isao Harimoto

As a "Zainichi Korean" — someone of Korean descent whose family moved to Japan during the imperial years between 1910 and 1945 — Isao Harimoto already faced discrimination before becoming a hibakusha. He was 5 years old when Hiroshima was bombed. His older sister died that day, and his widowed mother was never the same. Harimoto told The Mainichi, "There are people who may want to hold onto things, to remember and feel nostalgic. They tear up. But my mother wanted to forget. I think she wanted to completely erase her memories of that day."

Despite an injury he sustained a year before the bombing that disfigured his right hand, Harimoto went on to become a famous baseball player in Japan, and is believed to be the only hibakusha to do so. He still holds the record for career hits in Nippon Professional Baseball at 3,085. Even as a famous athlete, however, he couldn't escape Hiroshima. "Even if I live the same way as other people, I never know when aftereffects [from the A-bomb] might appear," he told The Mainichi in 2016.

He often attended the memorial event for Hiroshima, although as the years went on, it became more difficult for him emotionally. In 2019, he told a reporter for The Mainichi, "Even though I think I have to go ... I feel I'm tired of being angry."

Joe Kieyoomia

Nagasaki wasn't actually the primary target for the atomic bomb; the original plan was to drop the second nuke on Kokura, but bad weather meant the plane headed for its backup destination. This was very bad luck for Joe Kieyoomia, a U.S. POW who was imprisoned in Nagasaki that day.

Not only had he already survived the Bataan Death March, but because he was Navajo, he had been tortured in an attempt to break the code in that language being used by the U.S. The story of World War II's Code Talkers is incredible, but Kieyoomia was not one of them. "When they first made me listen to the broadcasts, I couldn't believe what I was hearing, " he said, according to "The Greatest U.S. Marine Corps Stories Ever Told: Unforgettable Stories Of Courage, Honor, And Sacrifice." "It sounded like Navajo, just not anything that made sense to me. I understood my language, but I could not figure out the code they were using. That made the interrogators very angry!"

Finally liberated almost a month after the bombing, his injuries were so bad that he did not return home to New Mexico for four more years. He went on to become an award-winning jewelry maker and finally received a Bronze Star for his service 40 years after the war ended. "I earned this Star," he told the AP (via The Santa Fe New Mexican). "I really suffered for this."

Setsuko Thurlow

Setsuko Thurlow was 13 when Hiroshima was bombed. She was lucky to survive, as many members of her family and hundreds of her schoolmates were killed.

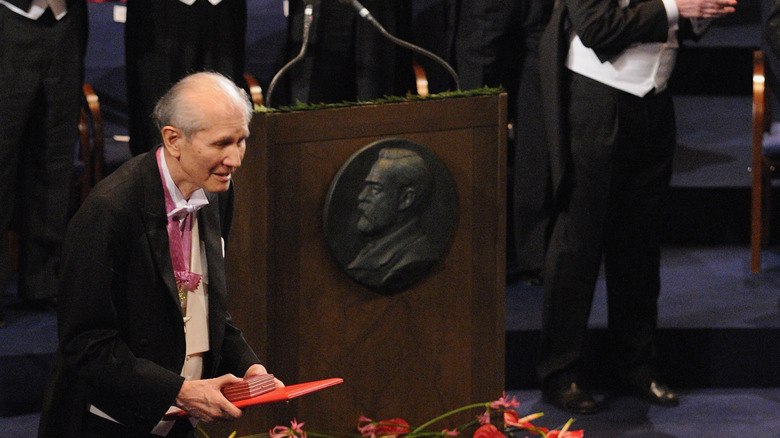

As an adult, she moved to Canada, where she is a peace activist and campaigner for denuclearization. Eventually, she helped form the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). When ICAN won the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize, she was one of two people who accepted the award (pictured). In her Nobel Prize lecture, she said, "Today, I want you to feel in this hall the presence of all those who perished in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I want you to feel, above and around us, a great cloud of a quarter million souls. Each person had a name. Each person was loved by someone. Let us ensure that their deaths were not in vain."

Thurlow has been awarded many other prizes and honors over the years, but her focus remains on getting results and the people who died from the atomic bombs. When 122 countries signed the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in 2017, she concentrated on the victims she sensed around her. "We made a vow that their deaths would have meaning, and that was for the total elimination and disarmament [of nuclear weapons]," she told the CBC, "so I was reporting to them."

Masaru Kawasaki

Masaru Kawasaki was 21 years old and had been drafted as a soldier, but was on sick leave in Hiroshima when the first atomic bomb dropped. He was very close to the epicenter and was still receiving treatment for his wounds decades later.

After the war, Kawasaki earned multiple degrees in music, specializing in the flute and composition. In 1965, he was awarded a UNESCO grant to study composition at The Juilliard School. He also conducted the Tokyo Symphonic Band for many years.

Despite many other hibakusha in the arts using the tragedies they survived as inspiration in their work, Kawasaki resisted doing so. He told The Asahi Shimbun, "I think the A-bombing was the greatest disaster that human beings have ever suffered, and that it should never happen again. Therefore, I had firmly refused to consider it as a theme for my work." But the need to express the emotions of the event finally won out: "At the same time, I have no words to console the souls of those who were killed by such a cruel twist of fate. I am filled with a feeling that all I can do is pray for them. Such a feeling inspired me to compose the prayer music..." Kawasaki composed "Prayer Music No.1: Dirge," which has been played at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony every year since 1975.

Tsutomu Yamaguchi

Tsutomu Yamaguchi was 29 years old when Japan was nuked. Astonishingly, he was present in both cities when the bombs dropped and is known as the man who survived both atomic bombs. He was on a business trip in Hiroshima on August 6 and managed to get home to Nagasaki by August 8. While he suffered some initial injuries, "Afterwards he was fine — we hardly noticed he was a survivor," his daughter Toshiko told The Independent. She explained that is why he chose not to advocate for denuclearization for most of his life: "He was so healthy, he thought it would have been unfair to people who were really sick." He returned to work designing oil tankers for Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and raised his family.

In his old age, however, Yamaguchi became more involved. He wrote a book about his experiences and took part in a documentary about victims of both atomic bombs called "Nijuuhibaku" ("Twice Bombed, Twice Survived"). At a screening of the film at the United Nations in 2006, he said, "As a double atomic bomb survivor, I experienced the bomb twice, and I sincerely hope that there will not be a third."

He also applied to change his status as a hibakusha. In 2009, he became the only person officially recognized as a "nijū hibakusha," a double survivor of both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings (although at least 165 people are believed to be in this category). He died the following year, aged 93.

Koko Kondo

Koko Kondo was an infant when Hiroshima was bombed, so she has no memory of the event. But she grew up watching her father, a minister, help victims of the bomb, including a group of 25 young women known as the Hiroshima Maidens who bore physical scars from the attack. These experiences had a deep effect on Kondo. She said when she was still a child, she would think, "I'm going to find the people who were on the B-29 Enola Gay, and I wanted to give them a punch, or a bite, or a kick. I want revenge," she told Hawaii News Now.

Kondo was put in an extraordinarily uncomfortable position at age 11 when her family was invited to appear on "This is Your Life," where they were introduced on camera to the pilot of the Enola Gay, Captain Robert Lewis. It was a horrible surprise to spring on the family, but fortunately, at least for the young Kondo, the meeting was cathartic. "I was staring at [Lewis'] eyes, and then I saw the tears come down. I was shocked. I've never heard such a story. He's a human being like me," she remembers. "I just wanted to touch his hand, my way of saying I'm sorry I hated you. I learned I shouldn't hate you, I should hate war itself."

Kondo says that at that moment, she chose forgiveness over hate. As an adult, she became a peace activist, giving talks about her experiences and working with denuclearization groups.

Shigeaki Mori

Shigeaki Mori was 8 years old when he survived the bombing of Hiroshima. He went on to become a historian of the tragedy he lived through, but focused on a very unusual set of victims: a dozen American POWs.

His magnum opus on the subject was "A Secret History of U.S. Servicemembers Who Died in the Atomic Bomb," which revealed what happened to these men for the first time. He then moved on to researching Australian POWs who died at Nagasaki. It was important for Mori to tell the world about how the bomb impacted more than just the Japanese. He told Stars and Stripes, "My ultimate hope is to send out a message that war deprives people of everything ... We should never repeat the mistake."

Mori made headlines when President Obama went to Hiroshima in 2016 and gave him a hug on camera. But seven years later, when a group of world leaders met in Japan, nothing had been done to reduce the world's supply of nuclear weapons, and Mori was not feeling as positive. "I just don't want all of this to end up being a dream," he told Reuters.

Shigeko Sasamori

Shigeko Sasamori was 13 when the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima, and the burns she suffered from the blast left her with terrible scarring. In 1955, Sasamori was one of 25 "Hiroshima Maidens" who made headlines when they traveled to the U.S. for reconstructive surgery to fix disfigurements caused by the bomb. While the trip was controversial for many reasons, for Sasamori it was life-changing, not just because of the medical care but also because it broadened her horizons. "Many people wanted to take care of us, so we [didn't] stay for a long time in each house — that way I met so many wonderful American people, local people," she told Colgate University.

Although Sasamori returned to Japan with the rest of the Hiroshima Maidens, she soon moved to the U.S., where she became a nurse and peace activist. As she explained to a U.S. Senate subcommittee in 1980 (via The New York Times): "I have a mission to tell people that this should not happen again. I tell people how horrible it was and how horribly we suffered, even though we were children. ... I don't feel angry at Americans. I don't want Americans to feel guilty. But I want them to help themselves and to take care of their children." Sasamori is pictured above giving a talk with Theodore "Dutch" Van Kirk, navigator of the Enola Gay, and she also spoke at an event with the grandson of President Harry Truman. She died in 2024, aged 92.

Takashi Nagai

Takashi Nagai was a radiologist who was already dying of cancer due to the effects of his work and had only been given three years to live when Nagasaki was bombed. He returned home to find his house demolished and his wife, Midori, dead from the blast. "There was nothing, nothing anymore around him. He had completely lost everything," Gabriele di Comite, president of the Friends of Takahashi and Midori Nagai Association, explained (via the Catholic News Agency). "He was living in a city which was completely destroyed. He had nothing anymore, he didn't have a house anymore, and he was not able to leave his bed."

Most people in that situation would lose all hope, but Nagai managed to find inspiration in his strong faith and desire to help other victims of the bombing find happiness again. Having converted to Catholicism years before, he became a religious hermit, living in a small hut where he wrote books while bedridden from his illness. His 1949 work "The Bells of Nagasaki" was a bestseller, and the book inspired a film in 1950. He became so well-known that everyone from Helen Keller to Emperor Hirohito made pilgrimages to speak with Nagai.

He died in 1951, outliving his doctors' expectations by three years. Both Takashi and Midori Nagai are in line for possible sainthood, having been elevated to the rank of "Servants of God" in 2021, which is the first step in the Catholic Church's process for canonizing a saint.