The Untold Truth Of John Wilkes Booth

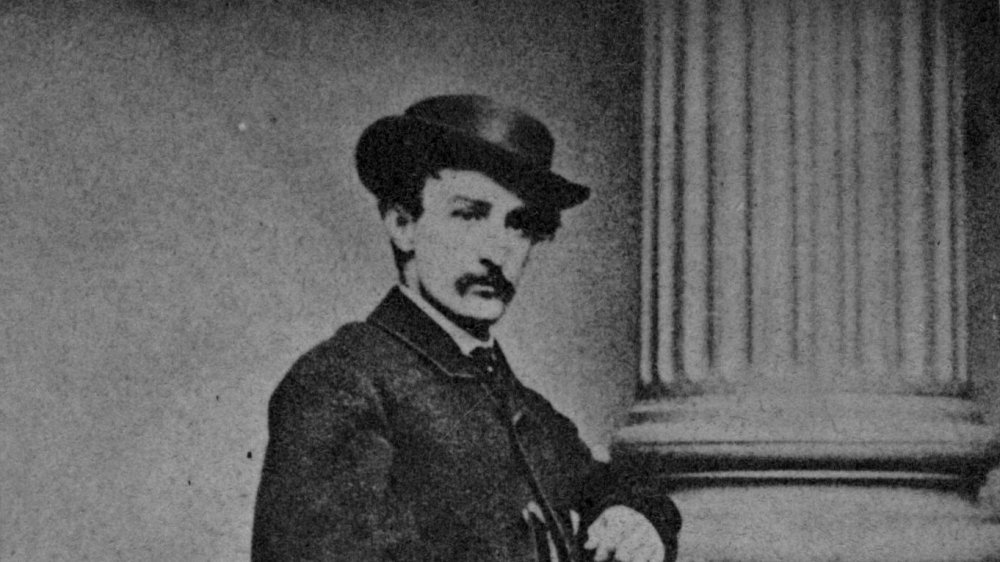

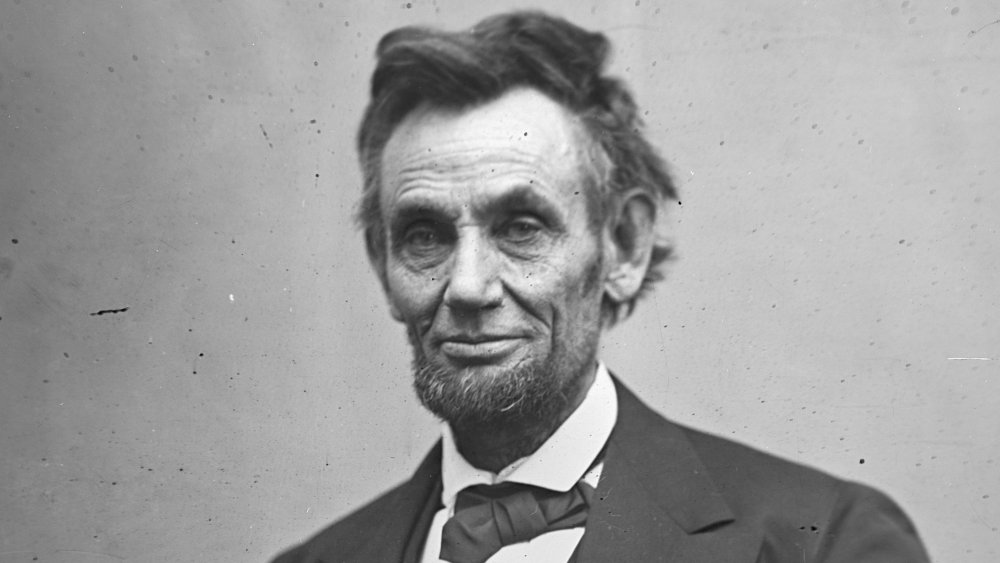

John Wilkes Booth infamously shot and killed President Abraham Lincoln in 1865. But what do we really know about the "dastard traitor and vile assassin?" While America has long scorned Booth for his dastardly deed which set the Union on edge, few know much about the man. And why should we care, anyway? After all, the murderer killed one of our favorite presidents, the one who wrote the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and ratified it two years later as the 13th amendment, freeing black slaves across the U.S., according to History.

Booth was not the only person to object to Lincoln's actions. He was, however, the one who dared to act on his own beliefs, even writing a speech about his position against Lincoln as early as 1860, according to Right Or Wrong, God Judge Me: The Writings of John Wilkes Booth. The budding actor had long been carrying out other clandestine acts on behalf of the South, including once smuggling quinine to the Gulf Coast to fight malaria, wrote his sister Asia Booth Clark. Indeed, there is much more to John Wilkes Booth than just his reputation as the assassin who shot President Abraham Lincoln.

John Wilkes Booth was born into acting

Born 1838 near Bel Air, Maryland, John Wilkes Booth was the ninth child of Junius Booth and his mistress Mary Ann Holmes, who would become his wife many years later. Battlefields notes Junius and Mary Ann were both British immigrants.

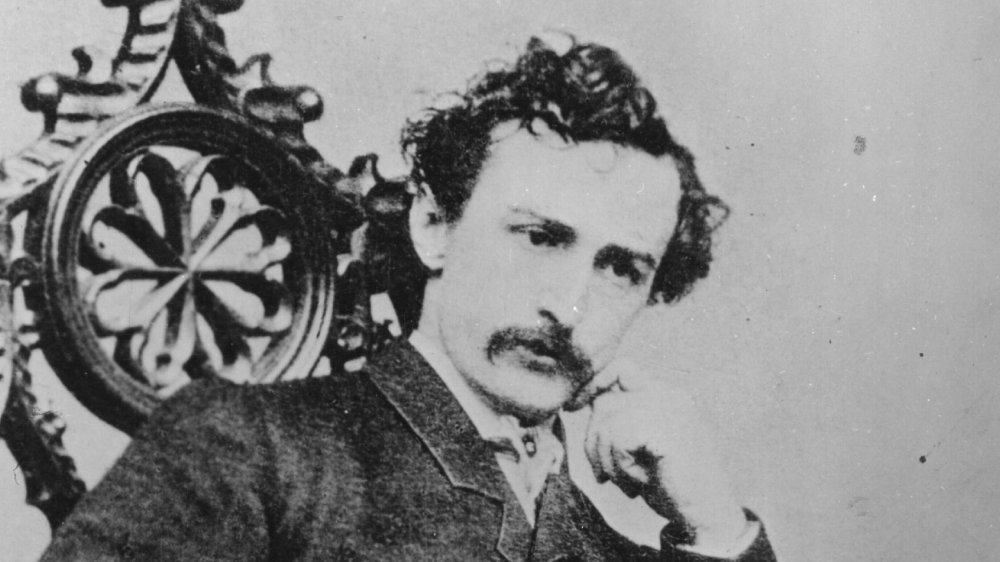

The Booths have been touted by Britannica as "one of the United States' most-distinguished acting families of the 19th century." Junius was a well-known Shakespearean actor and John's older brother, Edwin (pictured), had already followed in his father's footsteps to become "one of the 19th century's biggest stars," according to Folger, which notes Edwin was also one of Junius' illegitimate children.

Early on, John too showed excellent acting potential as he attended schools in Bel Air, Sparks, and Catonsville. But he was emotionally unstable as a child, which fed his growing egocentricity. By the age of 17, he was performing in plays like Richard III along the East Coast. But John also was honing his lust for politics, joining up with the anti-immigrant political party called the Know Nothings as his acting career developed. Still, he couldn't help envying Edwin, who performed on tour in both the U.S. and Europe. Edwin even founded Booth's Theatre in New York, reports HistoryNet. Although John and another brother, Junius Jr., sometimes appeared onstage with Edwin, neither achieved the same level of fame. And, it irked John greatly that Edwin supported Lincoln.

John Wilkes Booth, heartthrob of the stage

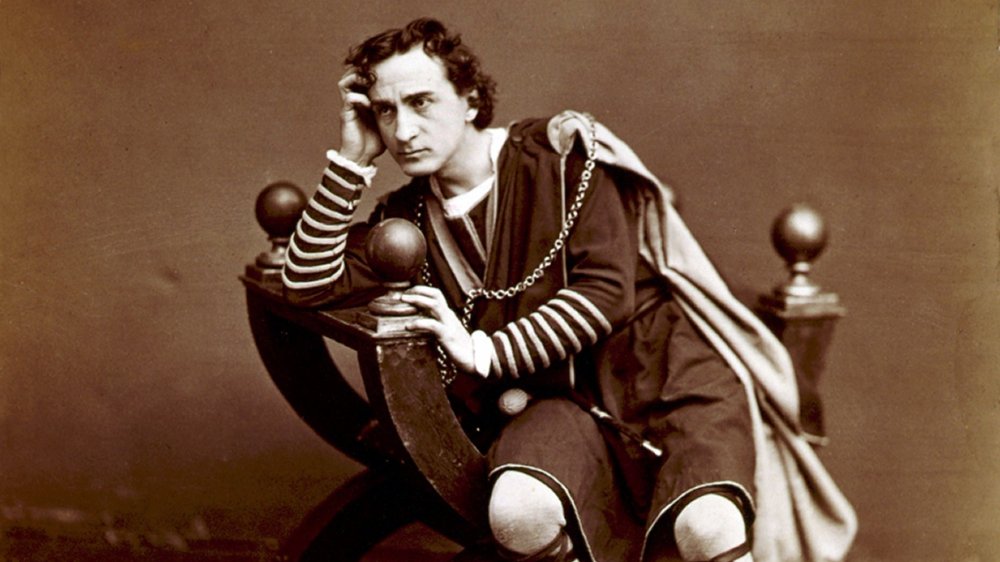

Edwin Booth's career perhaps spurred John Wilkes Booth to focus harder on his own, and he sported fake stage names as he worked on his craft. His hard work paid off, according to Travelanche: After spending a year at Philadelphia's Arch Street Theatre, Booth moved on to the Richmond Theatre in Virginia and performed 83 roles in 1858 alone. Even as he fine-tuned his acting career, however, Booth was quite vocal about being a Southerner. Britannica cites him as supporting the growing Southern cause—and the enslavement of Africans who had been brought to America against their will for generations (per History).

In 1859, John Wilkes Booth volunteered for the militia in Richmond. When abolitionist John Brown led a failed attack to free slaves at Harpers Ferry, according to Smithsonian Magazine, Booth was there to see him hang. Yet somehow, the actor-turned-rebel managed to keep his career afloat. By 1860, he was touring America. The people loved him, praising him as an attractive, charming man. Notably, John Wilkes Booth played to both Northern and Southern audiences. Brother Edwin, meanwhile, was staunch in his support of the North and limited his performances to those theaters in the Union states. This no doubt caused another rift between the two. And when Abraham Lincoln was elected president of the United States in 1860, it set John Wilkes Booth on fire with hatred for the man.

John Wilkes Booth fought for the Southern cause

By the time the Civil War broke out in 1861, John Wilkes Booth was among the most famous celebrities in the United States. He used his status to accost Lincoln's abolitionist efforts on his tours throughout the North and South. In Baltimore, American Northern Biography reveals, Booth even joined the Knights of the Golden Circle, a secret society against the North, which he did not share with his mother after promising her he would not join any military groups. Somehow, Booth managed to maintain his stardom and even a reputation as a gentleman. NPR recounts one time when he saved a young actress who got too close to the gas footlights, setting her dress on fire.

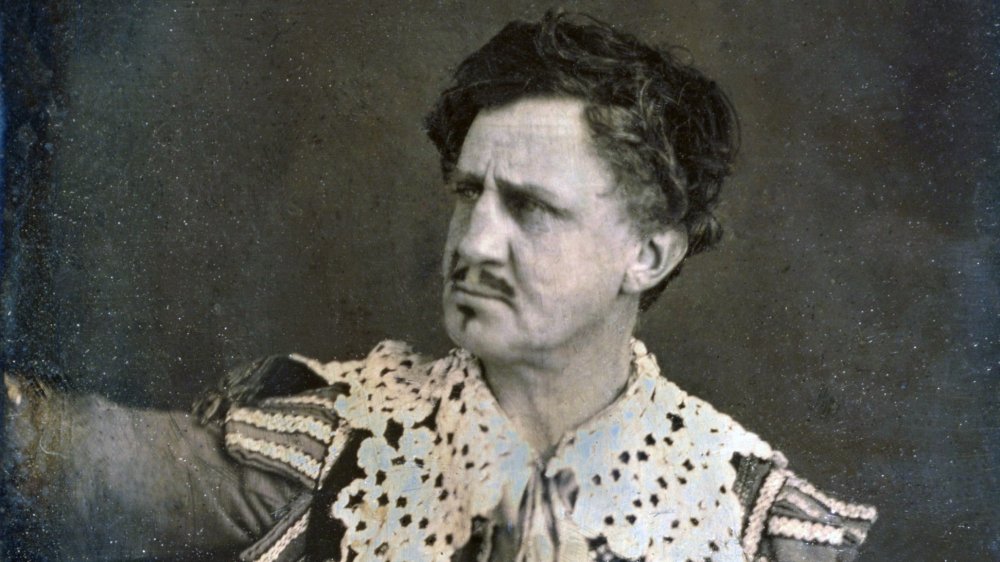

As John Wilkes Booth became more famous, however, he also began furthering his career by performing the same roles his father Junius (pictured) had and billing himself as J. Wilkes Booth. He also "began to develop a reputation as a womanizer and a considerable southern chauvinist." Womanizing can, of course, lead to consequences. In April of 1861, actress Henrietta Irving approached the actor, knife in hand. Booth had jilted Irving, and she wasn't about to let it slide. Attacking the actor, Irving failed in her endeavor to kill him, but not before inflicting a nice gash on his arm.

And, according to Find a Grave, Booth continued voicing his dislike for Lincoln, especially the president's proposal to free American slaves.

Was Lincoln's freeing the slaves a political move?

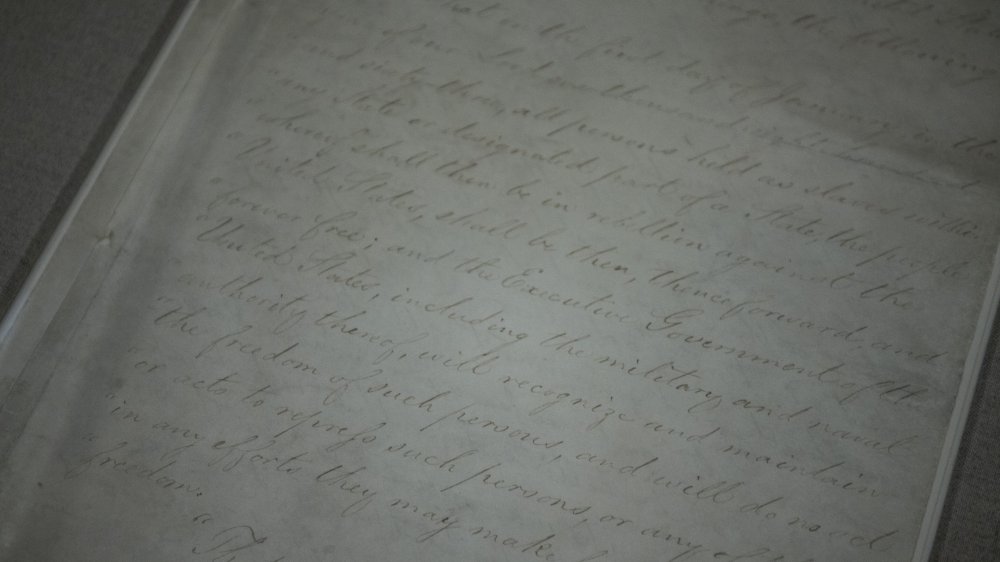

The National Archives, which retains Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, shows that the document was issued on January 1, 1863. The problem John Wilkes Booth, and many other Southerners, had was that the document indeed declared "all persons held as slaves" would be freed—but only in the Southern states. Those slaves in the Union, however, would remain as such. Furthermore, the Proclamation would only grant freedom to Southern slaves if the Union won the Civil War. Lincoln also announced black men would be accepted by the Union Army and Navy, ensuring that freed slaves would fight for the freedom of their fellow man.

Lincoln was very clear on his intent, according to the Library of Congress. In an address he gave his friend James Conkling, to be read at a Union meeting, Lincoln wrote, "I issued the proclamation on purpose to aid you in saving the Union."

But not everyone was buying the story. John Wilkes Booth felt Lincoln was actually trying to do away with the Constitution and thereby destroy the South, according to Teaching History. In the Southern states, meanwhile, slaves were unable to leave their owners en masse, but rather "began to slowly escape from slavery in small groups," says History Collection. It was not easy, since those who joined the Union often suffered discrimination anyway, even as they fought for the same side.

Booth's brother once saved Lincoln's son

Most ironically, Abraham Lincoln's oldest son, Robert Todd Lincoln (pictured), happened to be standing at the New Jersey train station sometime after his father had signed the Emancipation Proclamation, in 1863 or 1864 (the exact date is unknown). Robert had been waylaid by his mother from joining the army, reports Biography, and had instead been sent away to school. He attended Harvard University and tried to stay out of the public eye, states Mr. Lincoln's White House. It wasn't easy to do, as the media relentlessly followed him around. "He does everything very well, but avoids doing anything extraordinary," reported the New York Herald. "He doesn't talk much; he doesn't dance different from the other people; he isn't odd, outré nor strange in any way."

That day on the platform, according to the Vintage News, young Robert Todd Lincoln was pushed against a train car by the crowd. The student lost his footing, falling into the space between the car and the platform but landing on his feet. Suddenly the train began to move and might have taken Robert with it but for someone who suddenly grabbed him by the collar and pulled him to safety. Turning, Robert came face to face with his rescuer: Edwin Booth. According to HistoryNet, Robert would later say that Edwin's face "was of course well known to me, and I expressed my gratitude to him, and in doing so, called him by name."

Booth once planned to kidnap Lincoln

Whether John Wilkes Booth was aware that his brother had saved the son of Abraham Lincoln from injury or death is unknown, but by 1864 the actor was plotting to kidnap Lincoln, according to Britannica. Booth's original plan was to exchange Lincoln for Confederate prisoners, although General Ulysses S. Grant had stopped all prisoner exchanges to prevent the Confederates from increasing their military. But Lincoln would certainly get his attention. Boundary Stones explains that Booth recruited six men, including George Atzerodt, David Herold, and Lewis Powell (or Payne) to help.

Several plans actually failed before the group gave up. Booth, meantime, continued rising to fame. In his book, Fortune's Fool: The Life of John Wilkes Booth, Terry Alford wrote Booth could play a wide range of roles (via NPR). By 1865 he was so acclaimed that he had myriad fans, many of them women. Once as Booth left a theater in Boston after a performance, his followers crowded him to the extent that the manager had to tell them to "Back up, let him out, just let him walk to his hotel." In his effort to escape the crowd, according to Alford, Booth became the first known actor to have "his clothes torn by fans."

Booth's last minute plan to assassinate Lincoln

On the morning of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth found out Lincoln planned to attend a play, Our American Cousin, at Ford's Theatre (pictured here, after Lincoln's assassination) that evening. The Ford's Theatre website confirms that Booth was familiar with the playhouse, having performed there during November 1863. He starred in The Marble Heart, under his stage name, J. Wilkes Booth. Lincoln happened to attend the play on November 9. His sister-in-law, Mrs. Ben Hardin Helm, would remember Booth glaring at Lincoln as he performed onstage. "Mr. Lincoln, he looks as if he meant that for you," she whispered. Lincoln replied, "He does look pretty sharp at me, doesn't he?"

Famous Trials submits that Booth might have decided to kill Lincoln after "a speech urging Negro suffrage." This was probably Lincoln's last public address on April 11, 1865, during which History verifies Lincoln supported "limited black suffrage" for the first time. John Wilkes Booth's former friend, Louis Weichmann, later recalled watching the speech beside the soon-to-be-assassin. "Very professionally [Lincoln] said that there would never be any suffrage based on differences in the way people look," Weichmann said. "Upon this, Booth turned to the two of us [sic] and said, "That means n****r citizenship. Now by God I'll put him through!" History writes that Booth decided Vice President Andrew Johnson and Secretary of State William Seward should also be assassinated that same night.

The attacks on Seward and Johnson

John Wilkes Booth summoned Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt to meet him at a boarding house named Herndon House, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Powell and Herold were instructed to kill Secretary of State William Seward, and Atzerodt was assigned to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson at his suite at the Kirkwood Hotel. Booth also wanted to assassinate Ulysses S. Grant, but the Union general had left town that day, according to History.

Law 2 recounts that Herold accompanied Powell to Seward's home. Powell told the servant at the door that he had a prescription for the ailing Seward. Then he started towards the Secretary's room amid objections from the servant, Seward's son Frederick, and bodyguard George Robinson. Powell beat Frederick over the head with a revolver and cut Robinson across the forehead with a knife. Entering Seward's room, Powell next stabbed the man several times before fleeing.

Eastern Illinois University states that Atzerod, meanwhile, checked into the Kirkwood Hotel as part of his plan to kill Vice President Johnson. But as 10 p.m. rolled around—the same time Booth was about to assassinate the president—Atzerodt was actually working up his nerve by guzzling cocktails at the hotel bar. He never did carry out his portion of the plan, fleeing instead. But the hotel bartender later remembered Atzerod asking a lot of suspicious questions about Johnson, resulting in his arrest for conspiracy after Lincoln's murder.

John Wilkes Booth's assassination of President Abraham Lincoln

Earlier that day, John Wilkes Booth had gone to Ford's Theatre to get his mail, chatting with theater owner Henry Ford, writes Smithsonian Magazine. At 6 p.m., according to Britannica, Booth visited the now-empty theater again and fixed the door to the presidential box so it "could be jammed shut from the inside." Later, HistoryNet reports, Booth heard that Secretary Seward would likely recover and that Atzerodt had chickened out. Disappointed, Booth calmed himself by having a drink at a nearby saloon before going back to Ford's Theatre. Presenting a card to a presidential aide, Booth gained entrance through a lobby door, according to Famous Trials.

Lincoln's bodyguard, John Parker, happened to be off getting a beer, leaving the president unguarded. Booth easily approached the presidential box and opened the door, revealing Lincoln, his wife Mary, Major Henry Rathbone and his fiancée, Clara Harris, as they sat watching the play. Shouting either "Revenge for the South!" or "Freedom," John Wilkes Booth fired a single shot directly into the back of the president's head. Rathbone stood up and sprang forward to tackle Booth, who managed to slash him with a knife as he jumped over the railing to the stage below. But Rathbone had caught Booth's clothing, making for an awkward fall and causing Booth to injure his leg before escaping into the night.

Dr. Mudd was arrested for helping John Wilkes Booth

Britannica verifies that Abraham Lincoln died the next morning. John Wilkes Booth, meanwhile, met up with David Herold and skedaddled out of town. The pair fled to northern Virginia to the home of Dr. Samuel A. Mudd (pictured). The doctor's home remains an historic site, which claims that Mudd was a simple country doctor who treated Booth's leg and let the men "rest for several hours" before they went on their way. But an article by Roger Schlueter in the Belleville News-Democrat claims that George Atzerodt would later claim Booth planned his visit to Dr. Mudd, sending "liquors and provisions for the trip," and also that Booth and Herold stayed with Mudd for two days.

Mudd and his wife would later say they had no idea Booth planned to kill Abraham Lincoln, according to NPR. But Schlueter dispels this, writing that even if Mudd didn't know about Booth's actions, he "would have found out the next day when he ran errands in Bryantown." Also, the physician didn't notify authorities about John Wilkes Booth until long after the murderer had gone on the run again.

After Mudd was arrested, sentenced, and later pardoned, the phrase "his name is mud" has commonly been thought to have been coined because of the doctor. But Straight Dope confirms that the saying first appeared in print back in 1820.

Was John Wilkes Booth really killed?

John Wilkes Booth and David Herold next fled to a tobacco farm where they were advised to hide out in a thicket. The men stayed there for five days before taking off again and ending up in the barn of Richard Garrett's farm. There, on April 26, they were discovered. Eyewitness to History reports that Lieutenant Edward Doherty would remember that as Herold gave himself up, another officer, Sergeant Boston Corbett (pictured), shot at Booth to disarm him. Instead, the bullet hit Booth in the head, nearly in the same spot where Lincoln had been shot. Booth was dragged to Garrett's porch, where he died a short time later.

The Verge confirms that a few historians doubt it was John Wilkes Booth who died on Garrett's porch. Among them is Nate Orlowek, who examined supporting evidence for 40 years. Not surprisingly, certain of Booth's descendants are on Orlowek's side, although original accounts do claim the man had his personal diary on him when he died. Still, it turns out that the FBI kept a file on Booth beginning in 1922 and dating to as recently as 1977. Unanswered questions in the file include whether Booth really escaped, what the cryptic writing was in a boot he was wearing, and what happened to 27 sheets from his diary, which disappeared around 1867.

John Wilkes Booth's family was harassed, but he is buried in the family plot

Following John Wilkes Booth's death, according to Civil War Saga, authorities arrested his sister, Asia, and her husband, and ransacked their home. Most telling was a manifesto John had written, detailing Abraham Lincoln's kidnapping plan. John's brother Junius also was arrested. Meanwhile, cites Boothie Barn, Cyrena Hammond of New York would remember a man who tried to convince her Sunday School class that "had Mrs. Booth been a real genuine woman Wilkes Booth would never have committed the deed he did."

John's brothers also worried that his numerous girlfriends would come after the family—and they did. Boothie Barn also confirms that Edwin received letters from several would-be widows after John's death. One of them, Izola Martin Mills, claimed he was the father of her two children. Izola even managed to befriend John's sister Rose, who was noted as being "very kind" to the children. In 1937, Izola's daughter, Ogarita, even produced a badly written book, This One Mad Act, about John being her father, but nothing else came of her claim. Meanwhile, Find a Grave confirms that John Wilkes Booth's remains were finally given to the family in 1869. He is buried in the family plot, where his headstone remains unmarked.