The Entire Timeline Of The Bible's Old Testament Explained

Summing up the entirety of the Bible's Old Testament can sound like a daunting task. However, there's a narrative through-line that makes for compelling reading as it follows the first humans to the first patriarchs, then through the dramatic ups and downs that followed their descendants as they became the Israelite people. And while there are plenty of divinely delivered lessons along the way, the collected texts are not merely religious polemics, but a dramatic, generations-long story with a varied cast of characters. Take the ancient Israelite David, who rose from obscurity to become a military hero, a fugitive fleeing a paranoid ruler, a triumphant king in his own right, and finally a victim of his own imperfect humanity — and he's just one person in a sea of people bearing similarly dramatic tales through this often interconnected narrative.

Some books and sections of the Old Testament were, by necessity, left out of the following narrative. Texts that focus almost entirely on poetry or wisdom literature, such as Lamentations or Psalms, can certainly provide deep meaning and religious guidance, but don't necessarily move along the overarching story of the Old Testament. Others, like the book of Job, are tidily self-contained but difficult to place within that narrative. Meanwhile, some especially lengthy sections, from the infamous "begats" listing many generations to loving but admittedly long-winded descriptions of places and things like the Israelite tabernacle, weren't quoted verbatim. Ultimately, a text's presence or absence in the narrative here is not a judgment on its importance or meaning relative to the rest of the Old Testament.

Creation

In the very beginning, Genesis says that "the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep." Then, God called into being, well, everything, starting with light. After delineating night and day, he created the firmament (heaven) amidst the waters, marking the second day of creation.

Next, the God of the Old Testament moved on to the rest of creation. After the firmament, God caused the waters to recede and reveal dry land, where plants began to grow and produce seed, all on the third day. By the fourth, there were "lights in the firmament," along with the sun and moon. Day five saw the creation of birds and watery creatures, and day six the emergence of land animals.

Here arrived the first humans; as Genesis 1:27 relates: "So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them." By Genesis 2, it was day seven, on which God rested. Curiously, this chapter also revisited the creation of humans in greater detail, wherein the man, Adam, is created out of dust after God determined someone should be around to farm plants and exercise dominion over the animals. When God realized Adam needed a companion, he caused the man to fall asleep and created Eve, the first woman, from Adam's rib. The two would live in bliss in the paradisiacal Garden of Eden ... for the time being.

Adam and Eve rebel

With Adam and Eve established in Eden, conflict entered the narrative. In the very first line of Genesis 3, this was personified in the form of the serpent, "more subtil than any beast of the field." It's not clear just what the serpent's problem was, though many people identify it as Satan (Genesis never confirms this).

Adam and Eve had been told by God to avoid eating or even touching fruit from the tree in the middle of the garden, lest they die. But the serpent approached Eve and suggested she wouldn't die and would actually gain knowledge of good and evil. Eve, intrigued or at least fooled, ate the fruit. She then gave the fruit to Adam, who also ate. The two really did gain knowledge, including the sudden understanding that they were nude. They covered themselves with leaves and hid from God, but were found anyway.

Naturally, God uncovered what had happened and began doling out punishment. The serpent was cursed to crawl on its belly and always be at odds with humans. Eve was given painful childbirth and told that her husband "shall rule over thee." Adam was doomed to toil and labor alongside his wife, and both would die, with God concluding they will return to the ground, "for out of it wast thou taken: for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return." Then, the pair were banished from Eden, now gated and guarded by angels bearing flaming swords.

Cain and Abel originate rivalry and murder

Expelled from the Garden of Eden, Adam and Eve began to make a life for themselves in the harsh outside world. Soon enough, Eve gave birth to two sons: Cain, then Abel. Cain became a farmer and Abel a shepherd. When the brothers each brought an offering to God, Cain took a harvest as his offering, while Abel sacrificed the first animal from his flock that season. The sheep was pleasing to God, but Genesis 4 says that he wasn't so impressed by the produce, claiming "unto Cain and to his offering he had not respect."

Cain was put out, but God told him "If thou doest well, shalt thou not be accepted? and if thou doest not well, sin lieth at the door." Nonetheless, Cain then murdered his own brother, presumably out of anger and jealousy that the younger sibling was so favored.

God asked Cain where Abel was, with Cain now infamously replying, "Am I my brother's keeper?" Yet God knew that Abel was the first murder victim and therefore cursed Cain to wander, though anyone who attempted to kill him would face God's wrath. Eventually, Cain found his way to the land of Nod, married a wife (no word on where this mysterious spouse comes from), had children, and established a city. It's unclear how Adam and Eve reacted to the death of their son and the banishment of the other, but the chapter concludes with them having another son, Seth, perhaps in addition to yet more children.

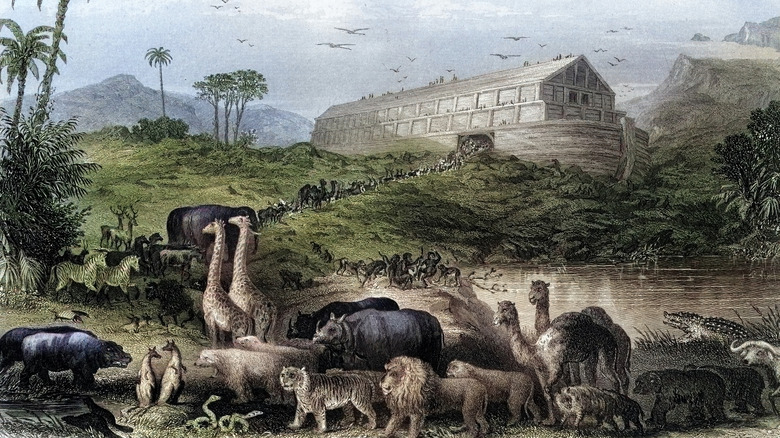

Noah faces the Great Flood

By the time of Noah, things were looking pretty bad to God. Yes, the generations that followed Adam and Eve had multiplied as commanded, but things had grown strange by Genesis 6, when the mysterious "sons of God" began to take human wives and "there were giants in the earth in those days." And so in time, "God saw the wickedness of man was great in the earth" and began to have doubts about the whole venture of creating these troublesome creatures. He decided to destroy humanity, beasts, and birds, but found that a righteous man named Noah and his family were good enough to survive the impending destruction.

Speaking to Noah, God commanded him to build an ark, a massive boat that would carry his family through a tremendous flood and hold two (or seven) of every beast to reestablish life after the catastrophe. Noah did just that, and the vessel's animal and human passengers survived 150 days aboard the ship. When the waters stopped, Noah sent out a series of birds, with a dove finally returning bearing an olive leaf to demonstrate that the flood had really ceased.

Having disembarked, Noah built an altar and prepared burned offerings, leading to God's promise in Genesis 8:21 that "I will not again curse the ground any more for man's sake; for the imagination of man's heart is evil from his youth; neither will I again smite any more every thing living, as I have done." However, part of Noah's untold truth is that his story may have been inspired by earlier Mesopotamian flood myths.

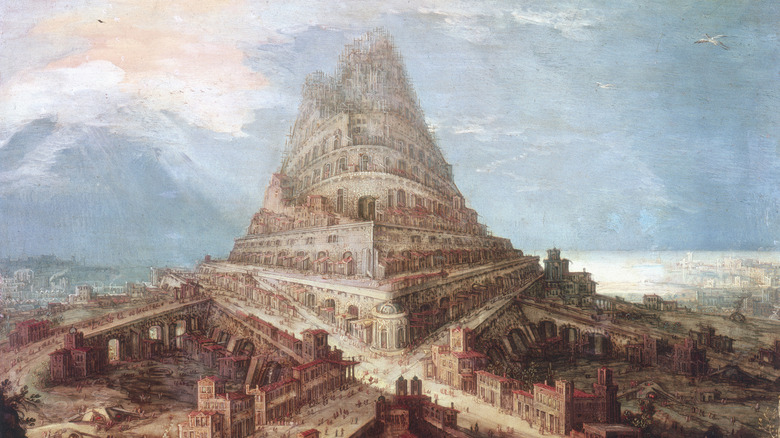

The Tower of Babel creates confusion

After just barely making it through the flood via Noah and his family, humanity didn't waste much time making trouble. At one point, a group of humans got together and, after establishing a city on the plains of Shinar, decided to build a tower. As in, a really, really big tower. It helped that, as Genesis 11 explains, they all spoke the same language, as indeed did every human in existence. That enabled them to use their combined know-how to fire bricks, assemble them with mortar, and build a tower so very tall that it could perhaps reach heaven.

This may sound preposterous to modern folks, but the Tower of Babel may have existed in some form. In the Old Testament, though, God saw the people doing this and became unsettled by the realization that they really might do just such a thing. "Go to, let us go down, and there confound their language, that they may not understand one another's speech," he said. With their language now unknown to one another, the mighty construction project failed and they scattered. The place, now known as Babel, became a byword for unintelligible speech or nonsense words.

Abraham becomes a patriarch

At first, Abram was just another pastoralist. Then, God spoke to him. As related in Genesis 12, God told Abram to pick up stakes and move, saying, "And I will make of thee a great nation, and I will bless thee, and make thy name great; and thou shalt be a blessing." Abram took his wife Sarai and moved into Canaan, where God promised that his descendants would occupy that land. But they kept moving, going through a famine-stricken region into Egypt, where Sarai was briefly detained by the pharaoh, who hoped to marry her. Abram, fearing trouble, pretended Sarai was his sister; upon finding out the truth, the pharaoh handed Sarai back over and told them to go on their way.

Eventually, Abram and company made their way back to Canaan. Because Sarai couldn't have children, she gave her handmaiden, Hagar, over to Abram. Hagar subsequently had Abram's first son, Ishmael, and though Sarai and Hagar fought — with a pregnant Hagar at one point fleeing, then returning — the two were pushed to get along by divine mandate (though Hagar is later expelled again).

By the time Abram was 99, per Genesis 17, God appeared to him and made a covenant to fulfill all the earlier divine promises. This included circumcision for men in his household, as well as a change of names for Abram to Abraham and Sarai to Sarah. Eventually, Sarah conceived (after laughing at the declaration of three angelic visitors that she would become pregnant) and had her own son, Isaac.

Sodom and Gomorrah are destroyed

Sodom and Gomorrah were two cities full of sin, as far as Genesis describes them. Not bad enough to wipe the slate of humanity clean again, but enough for some destruction to rain down from the skies. Abraham pleaded with God to spare the cities, for fear that someone righteous lives there. And, in fact, there was: Abraham's nephew, Lot.

God said he would spare the cities if even 10 good people were there, but it appears that only Lot and his family were righteous enough. A pair of angels, masquerading as men, appeared and were spared from an unruly crowd by Lot. In a display of extreme hospitality, Lot even said to the crowd in Genesis 19:8, "Behold now, I have two daughters which have not known man; let me, I pray you, bring them out unto you, and do ye to them as is good in your eyes: only unto these men do nothing; for therefore came they under the shadow of my roof."

That didn't come to pass — the disguised angels instead pulled Lot indoors and stuck everyone outside blind. The angels told him to escape with his wife and two daughters, but that they were not to witness the coming destruction that would consign the settlements to those Biblical cities lost to time. Lot complied, though his wife looked back at the last minute at the utter destruction wrought by "brimstone and fire from the Lord out of heaven" and was transformed into a pillar of salt.

Isaac takes up the mantle

Genesis 22:2 records God speaking to Abraham and referring to his child as "thine only son Isaac, whom thou lovest." Only, as the rest of the chapter reveals, this came with a terrible request: Isaac was to be offered up as a human sacrifice to God. Abraham acquiesced, though he semi-lied to Isaac when the boy wondered what they were going to sacrifice, telling his son, "God will provide himself a lamb." Abraham was about to sacrifice his own son when an angel stopped him at the last second — it was, apparently, a test to determine just how much Abraham was ready to follow orders. A ram, conveniently trapped in brush nearby, stood in for Isaac as the sacrifice.

Whether or not he was traumatized by the event, Isaac clearly stayed within the covenant established by his father. Just a couple of chapters later, he married after Abraham told a servant to bring a woman from outside Canaan. The servant traveled to the city of Nahor and waited at a well, praying to God to reveal a kind young woman who would provide water for him and his camels.

Rebekah appeared and did just that, and the servant successfully bargained with her father, Bethuel. Isaac married her, finding love and comfort after the death of his mother, Sarah. Though Abraham married another woman, Keturah, and had more children, he, too, "gave up the ghost, and died in a good old age, an old man, and full of years," per Genesis 25:8.

Jacob cheats his brother Esau

Isaac and Rebekah eventually conceived children together, but Rebekah found the pregnancy troublesome. In Genesis 25:23, God told her that "Two nations are in thy womb, and two manner of people shall be separated from thy bowels; and the one people shall be stronger than the other people; and the elder shall serve the younger." That first twin was the hairy Esau, followed closely by Jacob clutching to his elder brother's heel. Their father, Isaac, preferred Esau, while Rebekah took a shine to Jacob — who ended up as one of those notable Biblical figures who you might have wanted to avoid in real life.

Once they were adults, Esau, exhausted from working in the field, came in and practically begged his brother for food. Jacob refused until Esau desperately agreed to give over his birthright. When Isaac, having lost his sight, felt his end nearing, he called Esau to him and asked for his favorite meat dish before he blessed his son. Overhearing this, Rebekah hurried to Jacob and set up a plan wherein she would cook the meal and Jacob, pretending to be Esau with the help of some hairy goat skins, would present it.

Isaac was fooled and gave his blessing to Jacob instead. When Esau arrived later, the ruse was revealed, but it was too late (blessings being apparently limited in quantity), and an embittered Esau vowed to kill his brother. Yet again, Rebekah steps in and warns Jacob, telling her favored son to flee to the home of his uncle, Laban.

Jacob flees and marries

Having lied to his father and cheated his brother Esau out of his birthright, Jacob decided to leave town. Under his mother's direction, he made his way to the household of his uncle Laban with the promise that Rebekah would send for him when Esau had cooled down. Isaac at least managed to give Jacob a blessing and told him to pick a wife from among Laban's daughters. On the way, he had a dream of angels going up and down a great ladder, with God at the top, promising that the land on which Jacob was sleeping would become his own, saying in Genesis 28:15, "I am with thee, and will keep thee in all places whither thou goest."

Laban took Jacob in, but soon argued that Jacob ought to work for him and earn wages. Jacob promised to labor for seven years to marry Rachel, the beautiful daughter of Laban who first caught his eye. Laban agreed, but once the seven years had passed, switched in his elder daughter Leah — some have argued that Rachel was beautiful, but Leah's looks were rather more plain — in the dark wedding tent. Jacob, though clearly put out, agreed to another seven-year stint to earn the right to marry Rachel, which Laban honored the second time.

Echoing the story of his grandparents, Jacob conceived children with Leah but none with Rachel; the latter gave Jacob her servant, Bilhah, and claimed any children delivered via Bilhah as her own. Leah, getting older, did the same with her own servant, Zilpah. Then, Rachel finally delivered her own son and named him Joseph.

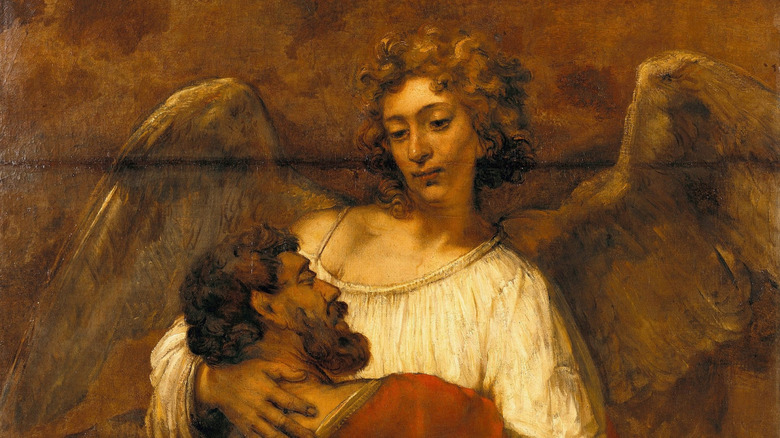

Jacob wrestles with God

Following the birth of Joseph, Jacob told Laban that it was time for his family to leave, but Laban protested and asked Jacob to name his pay. Jacob replied that he only wanted to take the spotted or speckled animals from Laban's flock. But Jacob craftily encouraged the stronger animals to mate more frequently, leading to his own share of the multicolored animals increasing.

With Laban's sons complaining, Jacob had a dream to leave abruptly and secretly. His family left, but not before Rachel took some religious items. Laban pursued them, but when he entered Rachel's tent, he could not find them. Rachel, sitting on the camel's saddle where she'd hidden the items, gave the excuse that she was experiencing her monthly period and could not stand to greet her father. Laban left unsatisfied, though not before Jacob gave his father-in-law a piece of his mind.

On the journey back to his homeland, Jacob spent a night alone by a river crossing. As the account goes in Genesis 32, he wrestled an unnamed man there. The two tussled until dawn, when the mysterious stranger touched Jacob's leg and dislocated it; even then, Jacob refused to let go "except thou bless me." The man said, "Thy name shall be called no more Jacob, but Israel: for as a prince hast thou power with God and with men, and hast prevailed." Jacob then called the spot Peniel, explaining, "for I have seen God face to face, and my life is preserved."

Joseph goes to Egypt

Jacob's family wasn't done with sibling conflict, as the story of his young son Joseph attests. Back in Canaan, Joseph was clearly his father's favorite, as evidenced by the gift of a colorful coat. Then he began to have prophetic dreams, in which his family and even the sun and stars bowed to him. This drew the ire of his brothers, who plotted to kill him but instead sold him into slavery. However, they did present Joseph's coat — dipped in animal blood — to their father as evidence that he had died.

Joseph made his way to the household of Potiphar, a high-ranking Egyptian official who was impressed enough to make Joseph his household overseer. While Joseph proved honest, Potiphar's wife was less so; she tried to have an affair with Joseph and, when rebuffed, claimed he'd assaulted her. Joseph was jailed but, after successfully interpreting the dreams of Egyptian officials, came to the pharaoh's attention. When interpreting the pharaoh's own dreams, Joseph said they were a warning of famine and that the kingdom should build up grain stores. When he was proven right, he was promoted to vizier, effectively the second-in-command of Egypt.

Eventually, Jacob's family traveled into Egypt to buy up some of its stored grain, but they did not recognize Joseph when they arrived. They eventually reunited, Joseph forgave his brothers, and the family was whole again. Even though he had prospered so greatly amongst the Egyptians, he asked that his body be returned to Canaan for burial (which wouldn't begin to happen until the Israelite exodus, with Moses seeing Joseph's bones carried out of Egypt).

Moses flees from Pharaoh

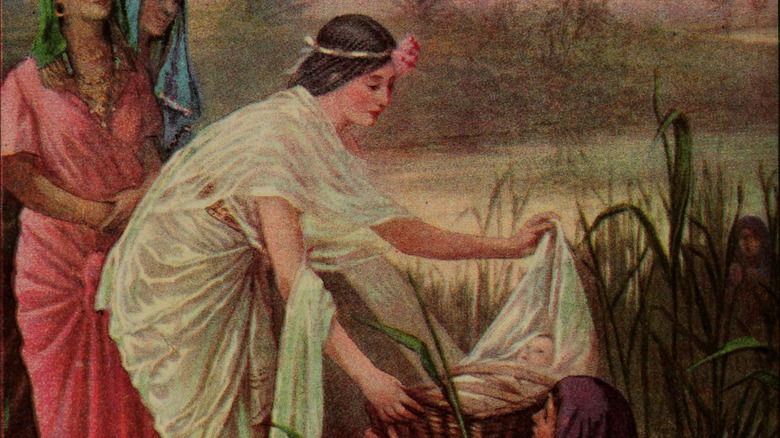

Moses had a rough start in life, to say the least. The son of a Hebrew woman, his people were enslaved by the Egyptians (at least as the book of Exodus claims, though actual historical or archaeological evidence hasn't exactly been forthcoming). What's more, the pharaoh commanded that all the male Hebrew children were to be killed, lest too many of them be born and represent a serious obstacle to their enslavement.

Moses' mother (who isn't identified as Jochebed until Exodus 6:20) therefore hid her newborn son until he was 3 months old, at which point she couldn't conceal him any longer. In a desperate move, she put him in a small vessel made of reeds coated in pitch and set him afloat on the Nile. Pharaoh's daughter, bathing in the same river, came across the baby and identified him as a Hebrew child, but still wanted to raise him. She called for a Hebrew woman to nurse him ... who just happened to be Jochebed herself.

Once older, Moses came upon an Egyptian man striking a Hebrew one and killed the aggressor, hiding his body. But he wasn't very good at concealing the act, as two Hebrew men later intimated that they knew all about it. In fact, so did Pharaoh, who wanted to kill Moses for the crime. Moses fled to Midian, where he married Zipporah, the daughter of a priest, and they began to have children together.

Moses brings the Ten Plagues down on Egypt

By the end of Exodus 2, it's made clear that the enslavement of the Hebrew people was ongoing — and that God was taking notice. Moses, while tending his father-in-law's flock, came to a mountain called Horeb and encountered a burning bush, through which God spoke to him. God told Moses that he was the deity of Moses' ancestors, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. While Moses hid his face out of fear, God continued that he saw the Hebrews in bondage and didn't like it one bit. But, for them to finally be free, Moses would have to step up and speak with Pharaoh (the previous one, who wanted Moses killed, having died).

Moses protested, but God replied to do what was asked, saying in Exodus 3, "I AM THAT I AM" and that he would deliver the Hebrew people from Egypt "unto a land flowing with milk and honey." Moses and his brother, Aaron, did talk to Pharaoh, but were roundly rejected even after the pair turned all the water in the land into blood. God then commanded that nine more plagues be unleashed on the land, including darkness, pestilence, fire from the sky, and the deaths of firstborn children. The Hebrew people were spared this last plague by smearing the blood of a sacrificial lamb on their doorways, which God took as a sign to pass over their household — this is the origin of the celebration of Passover. This finally broke Pharaoh, who released the Hebrew people.

The Ten Commandments and the Golden Calf

With the Israelites now released from Egypt, they began to journey to their ultimate destination of Canaan. But it wasn't easy going. For one, Pharaoh changed his mind and commanded his forces to pursue the Israelites until they were trapped at the shore of the Red Sea. God commanded Moses to use his staff to part the waters, so the Hebrew people could walk to safety while God delayed the Egyptians with a pillar of clouds. When the Egyptians finally pursued, the sea fell back in on them.

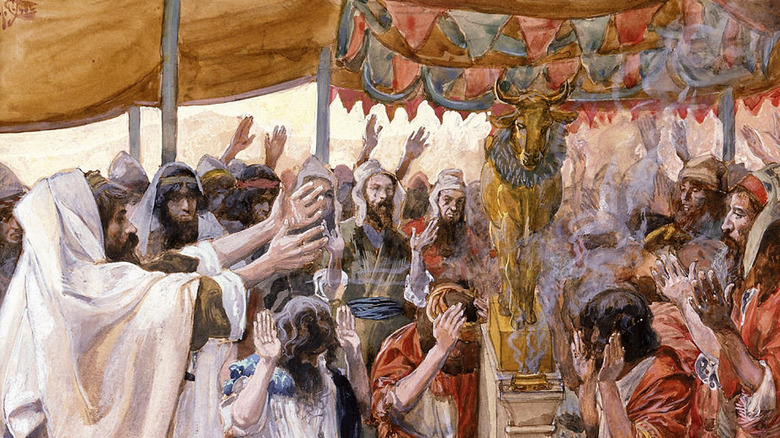

While traveling in the desert, God provided food in the form of miraculously appearing manna. When the group arrived at Mount Sinai, God spoke again to Moses and delivered the Ten Commandments, providing other details on maintaining the covenant with him, including the construction of the Ark of the Covenant. But, with Moses spending much time on the mountain talking to God, some of the Israelites below began to think that their leader had simply died up there.

Aaron collected gold from the people and melted it down to create a golden calf. The people worshipped the idol, which naturally made God angry when Moses descended from Sinai, alive and well. God wanted to destroy them, but Moses interceded. However, he did break the Ten Commandments tablets in anger and, in one of the moments often ignored in Moses' story, commanded the men of the tribe of Levi, who had not engaged in golden calf worship, to slaughter about 3,000 of the unfaithful.

Wandering in the desert

After the episode of the Golden Calf, the remaining Israelites constructed an elaborate tabernacle, a special tent that was the home of the ark and God's dwelling until they reached Canaan. Numbers 10 sees them finally departing Sinai, but it was no easy path forward, as many began to wonder aloud if Egypt was so bad, after all. Moses began to break down, but God stepped in and allowed other elders the gift of prophecy. He also delivered a bounty of quail meat, but followed that up with a punishment of disease. Even Miriam, Moses' sister, and his brother Aaron still complained, leading to Miriam's temporary brush with leprosy — cured only after Moses asked God to intervene.

In Numbers 13, the group reached the edge of Canaan, where Moses sent scouts to assess the possibility of overtaking it then and there. Only, the spies returned with a disappointing report: Canaan and its people seemed prepared to crush an invasion. The Israelites again despaired and complained about Moses, leading to yet more divine punishment. God told them that none of the group, save for the ever-faithful Caleb and Joshua, would live to see the Promised Land. Moses himself lost that chance in Numbers 20, after striking a rock to make it produce water for his thirsty followers, which God took as a sign of unfaithfulness and disobedience. God at least showed him the Promised Land from atop Mount Nebo in Deuteronomy 34, though Moses died thereafter and was reportedly buried somewhere in Moab.

Jericho falls

With Moses dead, his successor Joshua stepped into the role of Israelite leader with God's blessing. But that came with a significant task: it was finally time to take Canaan. Joshua set his sights upon the fortified Canaanite city of Jericho. Per God's instructions, Joshua's Israelite forces marched around the city every day for six days, followed by a round of seven marches on the last day. This culminated in a series of loud trumpet blasts and shouting, which, as the Biblical account relates, caused the walls of Jericho to tumble and the city to lay defenseless before the Israelites.

The following attack saw nearly everything and everyone in the city laid to waste. Only one household, that of a woman of ill repute called Rahab, was spared because she helped the two spies Joshua sent into the city before the attack. Israelites again offended God by seizing forbidden goods (or "accursed things," as the King James Version translates) from the city — these were meant to "come into the treasury of the Lord" instead, per Joshua 6. Thus, God set the Israelites up to fail at their next siege of the city of Ai. His anger was only appeased when the primary culprit holding the accursed things, Achan, was condemned via stoning alongside the rest of his household.

Judges sees dramatic upheavals

The book of Judges not only relates the occupation of Canaan and the death of Joshua, but also the subsequent downturn in righteousness of the Israelites. In this era, the people were led by judges who acted as local leaders. God's frequent punishments for idolatry and unfaithfulness often took the form of oppression. As God said in Judges 10:11-12, "Did not I deliver you from the Egyptians, and from the Amorites, from the children of Ammon, and from the Philistines? The Zidonians also, and the Amalekites, and the Maonites, did oppress you; and ye cried to me, and I delivered you out of their hand." But, he continued, they're still not setting themselves right, and therefore they ought to pray to their other gods and see what good it does them.

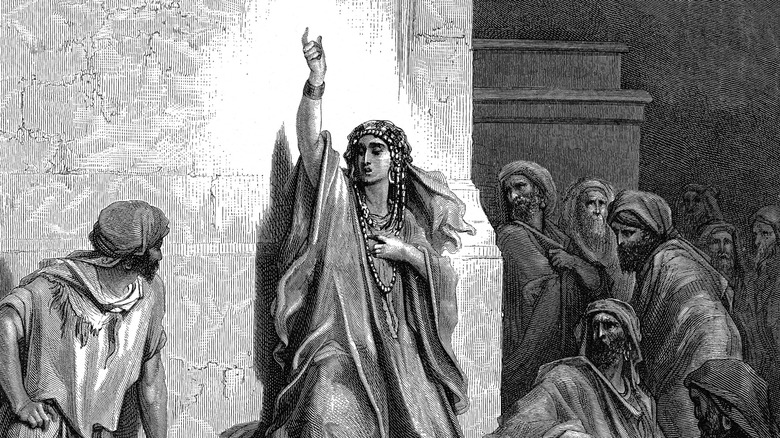

Still, there are some bright or at least interesting spots. In Judges 4, the people of Israel were again being oppressed, this time by the Canaanite king Jabin, though the more poetic Judges 5 says it's actually Sisera. Establishing herself among the most impactful women of the Bible, a judge and prophet known as Deborah told military commander Barak to assemble an Israelite army and face off against the Canaanites at Taanach. Canaan's soldiers were deeply frightened by the visible approach of God from Mount Sinai; then, their chariots were swamped in mire and soldiers were swept away by a rain-swollen river.

The commander, Sisera, escaped and attempted to hide in the tent of Heber, a Kenite who was supposed to be friendly to Canaan. Yet Heber's wife, Jael, dispatched Sisera with a tent peg — as prophesied earlier by Deborah — delivering final victory to Israel.

Samson deals with sin and betrayal

Amidst another oppression of the Israelites (this time from the Philistines) arose the infamous story of Samson. As it begins in Judges 13, his mother couldn't have children. An angel appeared and told her that this would change, but she must abstain from alcohol or unclean foods because her child was a Nazirite dedicated to God, who would save the Israelites from Philistine oppression. As an adult, he asked for a wife from the Philistines, causing great consternation, though Judges noted that this would allow Samson entry into the Philistine world in order to better overthrow them.

As he was on his way to be wedded, Samson learned that he had been granted God-given superpowers when he defeated an attacking lion. Soon, he also dispatched 30 Philistines. When the Philistines attempted to set a trap by raiding a Judean town, Samson broke out of the rope tying him down, grabbed a donkey's jawbone, and killed a further 1,000 men.

Samson seemed to be an unstoppable machine of God's vengeance, but then fell in love with Delilah, another Philistine woman who was acting as a spy. After many inquiries and denials, Samson finally told her that he'd never cut his hair, which, in that expression of his Nazarite vow, was the source of his strength. Delilah lulled Samson to sleep and cut his hair, after which he was turned over to the Philistines and blinded. Gloating, the Philistines bound him to two pillars in their public temple. Samson asked God for the return of his strength. His request granted, Samson pulled down the load-bearing pillars and caused the temple to collapse, leading to his death and that of everyone else inside.

Israel faces renewal under Samuel

By this point in the Old Testament narrative, things were looking pretty bad for the tribes of Israel. They had gone through multiple oppressions and other divine punishments, with little in the way of God-pleasing moral improvement. Into this void of righteousness stepped Samuel. He was born to Hannah, yet another woman in the Bible who was long aggrieved by her inability to have a child. Upon learning that she has conceived, she sings a song of praise in 1 Samuel 2 that not only speaks to God's greatness, but foretells the rise of an anointed king. Samuel wasn't to be king, but he did grow to become a great prophet and leader — all the more vital as the Philistines grew more threatening.

But God felt that Israel needed more chastising, so he allowed the Philistines to capture the Ark of the Covenant and display it in their temple to the god Dagon. God then sent a series of plagues upon the Philistines, until they brought the ark back to Israel — though the Israelites were meant to take this as a reminder to stay humble and follow all of God's commands if they want to maintain the covenant established so long ago. Still, they tripped up a bit almost immediately by going to an aged Samuel and demanding he select a king. Samuel didn't look kindly on this, but God told him to move forward with the enterprise anyway.

The monarchy begins under Saul

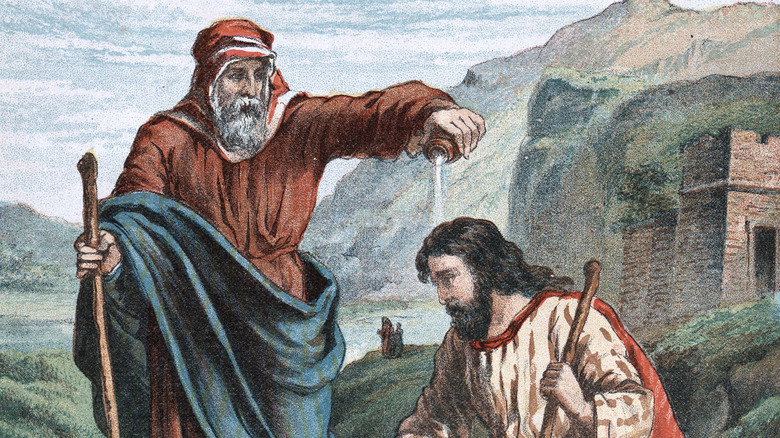

With God more or less sanctioning the selection of an Israelite king, Samuel centers in on Saul, "a choice young man, and a goodly: and there was not among the children of Israel a goodlier person than he," per 1 Samuel 9:2 (which also noted that he was tall in addition to being handsome). But while Saul was pleasant to look at and Samuel indeed anointed him as king, there was much trouble ahead.

As expected, Saul went to war against the Philistines and began to win battles, but not in a way that was precisely obedient to God. Saul proved to be impatient and even sometimes greedy, not always waiting for Samuel to offer sacrifices, and sometimes sparing foes like the Amalekite king Agag and the best domestic animals in the Amalekite kingdom. Samuel directly chastised Saul for such impertinence, telling him in 1 Samuel 15:22-23 that "to obey is better than sacrifice, and to hearken than the fat of rams. For rebellion is as the sin of witchcraft, and stubbornness is as iniquity and idolatry. Because thou hast rejected the word of the Lord, he hath also rejected thee from being king." Saul straightened up for the time being (including slaying Agag), but the rest of his downfall still lay before him.

David rises and defeats Goliath

With Saul having proved himself as a morally inconsistent king at best, Samuel was clearly frustrated. In 1 Samuel 15, he told Saul that God was all set to raise up a new king who would more carefully follow divine commands. Even though Samuel was grieved over all of this, God told him to carry on and visit Jesse the Bethlehemite, though he would have to pretend it was to make a sacrifice to God, to which Jesse just happened to be invited, lest Saul catch wind of the plot and kill Samuel. With all of Jesse's sons passing before him, Samuel saw that they weren't God's choice ... until the youngest, David, appeared. Samuel anointed him then and there.

Then an evil spirit began to plague Saul, so troubling him that his servants sought out a harp player to soothe his troubles. That musician happened to be none other than David, whose musical ability seemingly cured Saul. But David was also known as a budding warrior, as proven by his match against the heavily armored Philistine giant Goliath. Faced with such a foe, the Israelite army seemed doomed, but David told Saul in Samuel 17:32 that "thy servant will go and fight with this Philistine." Telling Goliath that he's armed with the power of God, David killed him with a simple sling and stone from his shepherding duties.

Saul took him in at this point, but the following chapters see him becoming increasingly paranoid, even while David acted as a great general in Saul's service. When Saul finally began to plot David's death, the younger man fled to safety.

Saul's downfall

Eventually, with David evading Saul (having once already spared the king's life) and building up an army of his own, Samuel died. Soon, David found safe harbor with the Philistines, who were happy to shore up an enemy of their own enemy. With a battle between Israel and the Philistines looming, Saul began to feel overwhelmed and frightened, made all the worse when it became clear that God would no longer speak to him. Desperate for answers, he sought out the help of a woman who could allegedly communicate with the spirits, even though Saul himself had outlawed such practices. The woman, now popularly known as the Witch of Endor, agreed to summon the spirit of Samuel. A spirit indeed appeared, though some later interpretations have claimed that this was the woman's own illusion or a demon masquerading as Samuel.

Whatever the true identity of the spirit, it had nothing but bad news for Saul. It said that Saul had repeatedly disobeyed God and incurred his wrath, and that Saul's forces would fall before the Philistines. "To morrow shalt thou and thy sons be with me," it concluded in Samuel 28:19. Saul fell down in despair, but went into battle anyway, where his sons, Saul himself, and other Israelites in his army died.

David's glory days

With Saul now dead in battle, the way was cleared for David to become the next king at the request of the disparate Israelite tribes. After a series of military successes — including defeating the Philistines — David brought the ark of the covenant into the city of Jerusalem.

It was, in general, quite a joyous celebration, with David himself dancing and plenty of sacrificing, trumpet blasts, shouting, and more to mark the occasion. David suggested building a permanent temple, but God demurred, saying that instead he would build a great dynasty of David and his people. In 1 Chronicles 28, David would also claim that God didn't want a bloody man of war, such as David was, to build the temple.

But though David was otherwise experiencing great triumph, this wasn't an entirely happy time for all. As the ark made its way into Jerusalem, a man named Uzzah dared to touch it when the oxen pulling it stumbled, and was struck dead by God for the impertinence. Meanwhile, David's wife Michal, the daughter of Saul who helped David escape from her father's murderous plot, was aghast at the sight of her royal husband dancing in the streets. She chastised him for dancing uncovered, as she saw it, but David replied that it was all for God, who had appointed him king over her own father, after all. Thus, 2 Samuel 6:23 brutally concludes, "Therefore Michal the daughter of Saul had no child unto the day of her death."

David brings trouble down upon himself

Things may have looked rosy for David in his early years as king, but he eventually succumbed to his imperfect human nature. In David's case, that happened after he went up to the roof of his palace one evening. There, he saw a woman bathing on another rooftop and was struck by her beauty. Learning that she was Bathsheba, wife of soldier Uriah, he had her brought to him. This encounter was not without consequence, as Bathsheba eventually told David that she was pregnant.

David schemed to send Uriah home to Bathsheba to make it seem as if the child was his, but Uriah wouldn't enjoy the comforts of his household while his commander, Joab, and others were in military encampments. David sent Uriah back to the front, carrying a letter to Joab in which David commanded in 2 Samuel 11:15 that Uriah be sent to "the forefront of the hottest battle, and retire ye from him, that he may be smitten, and die." Uriah indeed died, leaving David free to marry Bathsheba, but the prophet Nathan came to rebuke David. The king's young son who was conceived with Bathsheba then died.

As David aged, his surviving children grew violent, with one son, Amnon, abusing his sister, Tamar. Another son, Absalom, killed Amnon in revenge and then entered into open rebellion against David. This was eventually quashed with Absalom killed by Joab, but David was left to cry in Samuel 18:33, "O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom! would God I had died for thee, O Absalom, my son, my son!" Later, an ailing David would urge his son Solomon, the next king, to truly follow God's command.

Solomon builds the first temple

As a surviving son of David and his now-legitimate wife, Bathsheba, Solomon was in the line of succession, but David's other son, Adonijah, stood in his way. In 1 Kings 1, Bathsheba and the prophet Nathan worked together to ensure that Solomon would take the throne — and that both mother and son would survive the succession.

Bathsheba and Nathan each went into the chamber of David, now very old and ailing, and told him that Adonijah was attempting to seize power. David promised Solomon would be the divinely approved successor and called for Nathan and Zadok the priest to officially anoint his son. Adonijah at first showed deference, but quickly attempted to seize the throne once again, this time by taking Abishag – a woman who'd been a companion to the now-dead David — as a wife. Solomon saw this as another attempt to usurp power and ordered Adonijah killed.

That dark task done, Solomon proceeded to ask God for wisdom and, upon receiving it, had a temple finally built to elaborate and richly decorated specifications. Yet, like his father and Saul, Solomon begins to stumble. With a dizzying array of 700 marriages, – "king Solomon loved many strange women," 1 Kings 11:1 says — Solomon began to drift from the monotheistic ways of his people and introduced the worship of other gods. Solomon's God brought up an enemy, Hada the Edomite, who attempted to create a rebellion against Solomon.

The kingdom becomes divided

Despite the downturn in his reign and sins in God's eyes, Solomon survived and reigned for 40 years. Upon his death, he was succeeded by his own son, Rehoboam. But Rehoboam quickly stumbled, too, greedily increasing taxes and slavery to the point where a number of tribes led by Jeroboam rebelled. The formerly united kingdom split into two, with southern Judah left to Rehoboam, and the newly seceded group to the north forming the kingdom of Israel. Jeroboam even went so far as to build two new temples — but then installed a golden calf statue in each.

Clearly, Rehoboam and his advisors could have used a refresher on the book of Exodus and Moses' reaction to the first golden calf. Even without immediate bloodshed, this is clearly marked as a sin in the text, and, as the book of 1 Kings progresses, it's made all too obvious that northern Israel is on the wrong path when it comes to pleasing God. Judah isn't doing much better, though the list of its kings and their exploits shows that at least some attempted to be righteous in God's eyes.

Elijah rises as a prophet in troubled times

Into the north of this troubled, divided land came Elijah. He was to be a prophet of serious standing, even going so far as to raise the young son of a widow from the dead in his introductory chapter in 1 Kings 17. With a prophesied drought ongoing, he then appeared to Ahab, king of northern Israel. When Ahab asked if Elijah was the one who had been bringing such trouble, Elijah replied in 1 Kings 18:18 that "I have not troubled Israel; but thou, and thy father's house." He then called on the priests of the pagan god Baal to build an altar; he would do the same. Only Elijah's god responded to the altar-building and sacrifice with fire (Elijah then had the priests killed).

In 1 Kings 19, Jezebel, Ahab's wife, did not look kindly upon Elijah's exploits and threatened to have him killed. Elijah promptly fled to Beersheba in the southern kingdom of Judah, then further on into the wilderness. There, God appeared to him and told him to anoint Hazael king of Syria and Jehu king of Israel. Moreover, Elijah was to anoint a man named Elisha as his prophetic successor. On his journey back to civilization, he indeed found Elisha plowing a field and "cast his mantle upon him," provoking Elisha to follow Elijah.

Jezebel meets a shocking end

Jezebel was no one-off enemy of Elijah. As the Old Testament presents things, she was not just the wife of Ahab, but the true power behind the throne — and that power wasn't exactly benevolent. In 1 Kings 21, Ahab approached a man named Naboth, asking for his vineyard and offering a sum of money or another, nicer vineyard in exchange. Naboth turned him down and, when Jezebel found Ahab sulking about the matter, schemed to have Naboth stoned for trumped-up charges of blasphemy. With him out of the way, the vineyard was Ahab's for the taking. Elijah got wind of the affair and took the opportunity to prophesy against Ahab and his wife, concluding ominously in 1 Kings 21:23 that "The dogs shall eat Jezebel by the wall of Jezreel."

Ahab eventually died in battle against the Syrians and was succeeded by his son Ahaziah, who continued to displease God. Facing rebellion, Ahaziah also died following a fall in his home, though not after Elijah again spoke out against him and witnessed God bringing fire down upon the groups of soldiers who attempted to bring the prophet to the ailing king.

Yet Jezebel faced an arguably worse end, after a long time persecuting prophets and facing off against Elijah. With his anointed selection for king, Jehu, coming to take the throne from her son, Jehoram, Jezebel adorned herself and scornfully looked down from her royal window. But Jehu had the sympathies of the eunuchs attending her — they tossed her from the window to her death.

Elijah goes up to Heaven

Many prophets met mortal ends throughout the Old Testament, but in 2 Kings 2, it certainly appears that God made an exception for Elijah. With Elisha, Elijah traveled to Bethel, where prophets told Elisha that God intended to take Elijah away that day. The pair traveled on to Jericho, where Elisha received the same message about Elijah's impending departure. The same sequence repeated concerning the Jordan River, where the prophetic pair crossed after Elijah caused the river to split, Moses-style.

While walking, Elisha asked to receive a double portion of Elijah's spirit; the other prophet said it was difficult, but if Elisha witnessed the coming leave-taking, it would happen. Then, a chariot with flaming horses arrived and took Elijah in a swirl of wind. Elisha took Elijah's fallen cloak and left, again splitting the Jordan to pass. When he arrived on the other side, the prophets of Jericho offered to look for Elijah, but found no sign of him.

As Elisha returned to Bethel, a group of children taunted him for his baldness. Elisha called down a curse, and two bears appeared to grievously harm 42 of the children. Some have interpreted this as a sign of the broader disrespect Elisha faced, which was more obviously worthy of divine punishment and perhaps acted as a cautionary tale for budding skeptics.

Jonah meets whale

Among the prophets of the Old Testament, Jonah is perhaps one of the most human, proclaiming prophecies that are sometimes reversed and occasionally shirking his duties out of resentment and fear. Though the Book of Jonah contains a few different sections, the most famous incident featuring this prophet involves a watery creature. It begins when God told Jonah to travel to the city of Nineveh to preach there, but Jonah basically ran away — why isn't immediately clear — and boarded a ship. A great storm arose, and the prophet told the sailors to toss him overboard. They did and, when the storm abated, were convinced that the God of the Israelites was the real deal.

But Jonah's story did not abruptly end there. A great fish (often but not always interpreted as a whale) swallowed Jonah, who then survived in the creature's innards for three days. Jonah offered up prayers to God and promised to really, truly follow his directions — at which point the great fish spat Jonah back onto the land.

This time, Jonah dutifully made his way to Nineveh and preached, and the entire population, including the local king, repented their wicked ways. Their sincere reaction was enough to allay God's vengeance, but Jonah took this rather poorly, admitting he wasn't ready to forgive the people of Nineveh. God and Jonah had a discussion of sorts about the nature of forgiveness and compassion, and though the book still ended with a grumpy Jonah holding on to his anger, the merciful message of the book remains clear.

Isaiah has visions

While the Old Testament's prophets delivered plenty of doom and gloom, Isaiah managed to bring a bit more hope and joy into his message (though there were also hearty shares of doomsaying and warnings, too). Perhaps most importantly, during the tumultuous two-kingdom period, he spoke of a coming messiah, though he also spoke of a rather harrowing period of struggle and purification that awaited the increasingly corrupted Israelite people (who, God noted, would have hardened their hearts to Isaiah's message).

That change would not come until, as God tells the prophet in Isaiah 6:11-12, "the cities be wasted without inhabitant, and the houses without man, and the land be utterly desolate, and the Lord have removed men far away, and there be a great forsaking in the midst of the land." He later mentions captivity — specifically, the Babylonian exile in which the Israelites are driven from their land and effectively imprisoned — and offered hope for the new kingdom.

Isaiah then confronted Ahaz, the current king of Jerusalem and a descendant of the line of David, to tell him the kingdom's end was coming. Assyria would be its downfall, but a new king, the mysterious Immanuel (essentially, "God with us"), would eventually arrive to oversee a renewed and more just Jerusalem. He again referenced this messianic figure in Isaiah 32, saying "a king shall reign in righteousness, and princes shall rule in judgment."

Jerusalem falls

The Babylonian captivity wasn't a single, traumatic event. Instead, it was a series of conquests of the kingdom of Judah, in which the Neo-Babylonian Empire repeatedly forced some Jewish people to leave their Judean homes, while others were able to stay behind. From an archaeological and historical perspective, it's not clear exactly when the first such wave of deportation happened, but the Old Testament offers its own chronology.

The Biblical account in 2 Kings 25 states that Nebuchadnezzar's forces began a siege of Jerusalem in the ninth year of the reign of Zedekiah, king of Judah, and more specifically on the 10th day of the 10th month. That same accounting of dates is repeated in Jeremiah 52, with both accounts describing a brutal siege lasting into the 11th year of Zedekiah's reign. With the starving city crumbling, Zedekiah and his cohort attempt to flee, but are captured. The king's sons are killed, and Zedekiah himself is blinded and imprisoned for life. The Babylonian forces lay waste to the city and take away some of its inhabitants, though other Judeans are allowed to remain behind.

Both accounts end with a spare few lines describing an intriguing but short encounter between royals. After having moved forward 37 years, both state that Judean king Jehoiachin — Zedekiah's nephew and royal predecessor, whom Nebuchadnezzar had captured after a previous assault on Jerusalem — is called up out of imprisonment. His rescuer of sorts was the current Babylonian king, Evilmerodach, who restored some of Jehoiachin's royal privileges, including a throne, and gave him clothing and food for the rest of his life. Here, both the books of Jeremiah and 2 Kings end on this note of possible reconciliation, or at least a softening stance.

Ezekiel issues more prophecy

The first wave of the Babylonian exile included the priest and prophet Ezekiel, who had once been a resident of Jerusalem. Ezekiel 1 begins the book with its namesake prophet first seeing "that the heavens were opened, and I saw visions of God." Specifically, he saw a bright cloud containing four winged creatures, each with four faces — of a man, lion, ox, and eagle — and sitting atop a wheel. The four supported a glowing throned figure. Ezekiel could not make out the face, but said it could be none other than God.

The figure said the Israelite people were once again not honoring their holy covenant, and that Ezekiel was to deliver God's message to the recalcitrant people. He then saw a scroll before him, full of lamentations, which he was told to eat and then go preach. Having done that, he proceeded to deliver his message in sometimes shocking ways, from building and destroying a tiny model of Jerusalem to shaving his head and chopping at some of the hair with a knife, to eating food cooked using human waste as fuel.

Ezekiel continued his public chastisement, though God also promised a change would come, telling the prophet in Ezekiel 11:19 that "I will take the stony heart out of their flesh, and will give them an heart of flesh." But Ezekiel 33 relates the second and more final destruction of Jerusalem, including the destruction of its temple. By Ezekiel 40 and the following chapters, the prophet discussed the restoration of the temple and a renewed creation, ending on a hopeful note.

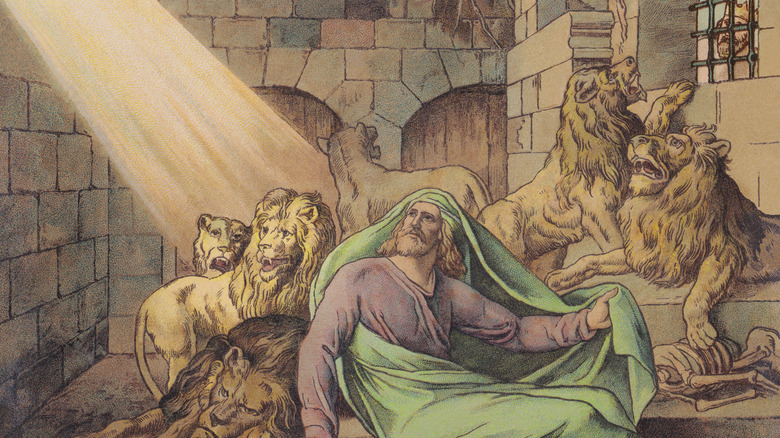

Daniel survives the lion's den

The book of Daniel begins with the introduction of Daniel and his three friends, Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah. During the Babylonian exile, they were selected to serve as teachers in royal circles and given the Babylonian-style names of Belteshazzar, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, respectively. When Nebuchadnezzar dreamed of a massive statue representing a series of kingdoms that was destroyed, Daniel interpreted it as a representation of corrupt earthly kingdoms ultimately destroyed by the cleansing arrival of God's kingdom.

Next, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego ran into trouble after refusing to worship a pagan statue. They were condemned to die in a blazing furnace, but the attending Nebuchadnezzar saw four men walking unharmed and unbound in the fires — the mysterious angelic fourth person being, as some have since interpreted, the future Son of God. The king called them out of the fire and praised their God. Later, Nebuchadnezzar would grow so prideful that God made him mentally unstable; only admitting his sin and praising God restored him. His successor, Belshazzar, later refused to humble himself and was assassinated. Then, like his three friends, Daniel also refused to worship the new king, Darius, causing him to be thrown into a den of lions — yet he survived, once again leading to praise for Daniel's God.

Daniel himself faced a strange dream of beasts, including a terrible horned one, representing a series of arrogant kingdoms and rulers eventually defeated by the Son of Man. In subsequent chapters, he faced similar dreams and visions, including one in which an angel explained that Israel was still sinful and would face a lengthened exile.

Cyrus facilitates the return of the exiles

Though the book of Daniel's final visions leaves the matter of just when the Son of Man would come to defeat arrogant earthly rulers up in the air, the Old Testament does make it clear that Babylonian captivity eventually came to an end. The book of Ezra begins with just that, showing the Persian king Cyrus reversing the decisions of his forebears and allowing Israel to return home and rebuild the temple. A group led by Zerubbabel made the trek and first recreated the altar, followed by the rest of the temple, which was met with celebration.

But, things weren't necessarily all joyful celebration and overwhelming emotion, as witnessed amongst the people of Israel upon their return and the rebuilding of the temple. During construction, the descendants of those who hadn't gone into exile attempted to help rebuild but were rebuffed by Zerubbabel, which led to unrest and the cessation of temple construction, though it was eventually completed. Still, it was clearly an uncomfortably shaky start to a long-awaited return and rebuilding.

Esther becomes queen and thwarts genocide

At this point in the Biblical narrative, the Babylonian exile had effectively ended, but many Jewish people had remained away from the homeland. The book of Esther, which is considered to overlap with the book of Ezra, focuses on one of those communities in ancient Persia, in the city of Susa. It begins with King Ahasuerus — commonly identified as Xerxes I – and his wife, Vashti.

In the account, the king threw a wild party and, deep in his cups, demanded that Vashti put in an appearance wearing her crown. Vashti refused; interpretations of this "no" include the unspoken notion that she was to appear wearing only her crown, or that she just didn't want to hang out with a bunch of inebriated men. Either way, Ahasuerus deposed her and held a beauty contest to locate a new wife. Esther, a young Jewish woman living with her cousin and adoptive father, Mordecai, won the attention of the king and married him.

Only, the king didn't know that she was Jewish. Queen Esther's weird situation grew all the more tense when the king's advisor, Haman, turned against Mordecai and the entire Jewish community. He persuaded the king to condemn all Jewish people, but the king was reminded of a time Mordecai saved his life, preemptively foiling Haman's plan. When Esther revealed her Jewish identity, that further prompted the king to publicly and violently turn against Haman. Ahasuerus then issued a new decree that countermanded his earlier one, stating Jewish people had the right to defend themselves against any attackers. The subsequent feasting is now commemorated by the Jewish festival of Purim.

Ezra and Nehemiah bring reform

By the time of Ezra, a number of Jewish people still remained in Babylon. But Artaxerxes, then the king of Persia, pushed for a second group of people to return to Jerusalem, this time led by the scholar Ezra.

Upon learning that some of the first group of Jewish returnees had intermarried with others who had remained around Jerusalem, including potentially some non-Israelites, Ezra grew aghast. "And when I heard this thing, I rent my garment and my mantle, and plucked off the hair of my head and of my beard, and sat down astonied," he wailed in Ezra 9:3. He then demanded a decree of divorce that would split up these inter-group marriages, to the point where even wives and their children would be pushed out of the community. However, this proclamation may strike some scholars as odd, given that other parts of the Old Testament (such as Malachi 2:13-16) are very explicitly against divorce of any sort.

Next, the Israelite Nehemiah arrived from his position in the Persian government, bearing royal permission to rebuild the shambles that were once Jerusalem's walls. The builders of the wall faced mocking and worse, especially after Nehemiah told some perceived outsiders in Nehemiah 2:19-20 that "ye have no portion, nor right, nor memorial, in Jerusalem." Unfriendly, yes, but the wall was rebuilt anyway. In Nehemiah 5, Nehemiah also did away with debt and bondage, as leveraged against the poor by their better-off countrymen.

Israelites are called to repent

Though things started out pretty well for Nehemiah, with the project of rebuilding Jerusalem's wall reaching its completion and a festival to celebrate, like so much of the Old Testament, things started to go askew. But, as Nehemiah considered the city in Nehemiah 13, he found that the people were once again violating the covenant, such as by setting up markets to work on the Sabbath. His response is to enact strict new mandates, including laws to honor the Sabbath by resting, forbidding marriage with non-Israelites, and pushing foreigners out of the city's temple.

In Christian contexts, the Old Testament typically ends with the book of Malachi, though some point out that Chronicles was the original and more hopeful endpoint. The book of Malachi isn't exactly a narrative, but its short four chapters do frame a kind of conversation between God and the people of Israel, showing that they still aren't living up to their covenant, even after the end of the exile. God called for repentance yet again, while also foretelling the coming of a messenger (later identified in the New Testament as John the Baptist). Though the book leaves it unclear whether or not anyone heeded that call, it does speak to the hope of restoring one's relationship with God.