The Real Reason Florence Nightingale Never Got Married

You'd think that being directly responsible for saving thousands of lives, of amassing and analyzing data that contributed to massive improvements in sanitation and health care, and honored by Queen Victoria herself would be enough. But no. Florence Nightingale never married. In Nightingale's era, women married — nay, were expected to marry, preferably to a man of at least some wealth and social standing, since women had very few property rights of their own. Nightingale came from such a family, but it seems that she realized early in her life that her true calling was nursing.

She had opportunities to marry, with at least four men asking for her hand, according to the UK's History Press. One ended up marrying Nightingale's sister, Parthenope; another, generally seen as the one by whom she was most tempted, was a philanthropist and poet, Richard Monkton Milnes. History tells us that she realized her "moral ... active nature ... requires satisfaction, and that would not find it" by simply living as someone's wife. She was convinced she was called to be a nurse.

In those days — she was born May 12, 1820, according to Biography — nursing was regarded as menial labor, and didn't involve much beyond showing up and doing little. At first, her parents objected to her career goals, but finally gave in. She studied in Germany, then returned to work at a London hospital. Within a year she was superintendent of the institution.

She was tireless in her quest for better, safer medical conditions

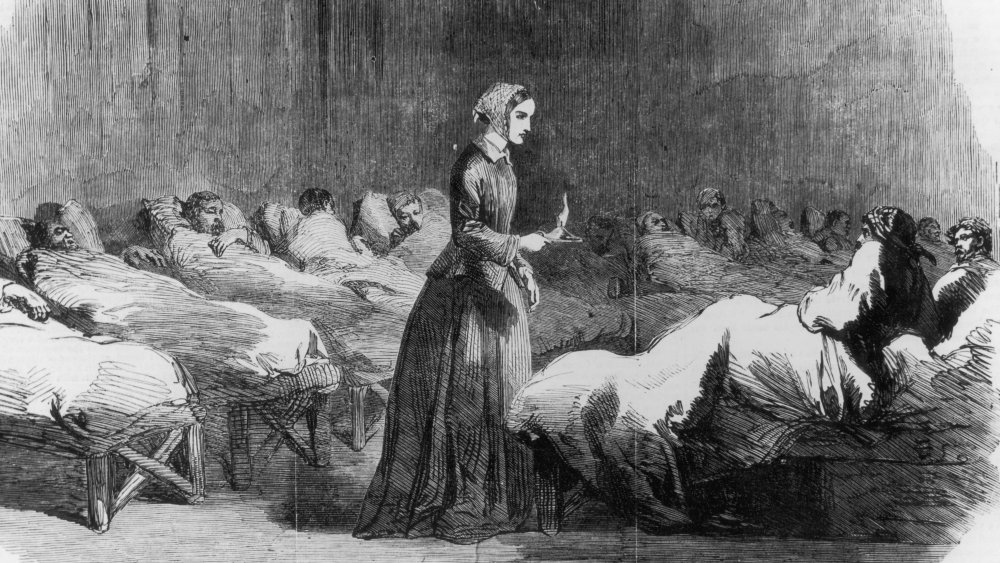

As she excelled, she analyzed what was going on around her. It was Nightingale who instituted heightened hygiene practices, backed up with statistical data. When England went to war with Russia over the Ottoman Empire — the Crimean War; the "Charge of the Light Brigade" was one of the battles — she was asked to organize medical care for the sick and wounded British troops. Men were dying far more frequently from preventable diseases — typhoid and cholera among them — than they were from the battlefield. Nightingale and her nurse corps set out to clean, to comfort, to clean more, to comfort more — she became famous for making rounds, checking on the wounded and ill late at night, the "Lady with the Lamp."

She created a Royal Commission to analyze mortality data from the conflict, leading to more reforms in health care. Although there is no question that her reforming spirit led to concrete improvements in medicine, her remarkable achievements as a statistician had an impact for generations to come.

Nightingale became chronically ill with brucellosis during her time in the Crimea, and never truly recovered. She was frequently bedridden for the rest of her life, though still active as a writer and consultant, giving advice for hospital care during the American Civil War. She died August 12, 1910. She was unmarried. But in a very real sense, immortal.