The 1906 San Francisco Earthquake Was Worse Than You Thought

Human civilization rests on a precarious foundation. People strive to overcome the elements, to build societies, and to assert themselves over nature, but the truth is, people are just one tiny part of a bigger whole, and the Earth — at any moment — can erupt in a rather volatile fashion. That said, while natural disasters are inherently uncontrollably, the human response to such disasters has often caused the most damage of all.

For example, look back on the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. On its face, the earthquake was a colossal and uncontrollable "act of God," which stole thousands of lives. When you pull back the layers of the official story, though, you can uncover a nightmarish fiasco of human errors, from poor building decisions, to the decision to combat fires with dynamite, to the implementation of a "shoot-to-kill" order, to the horrendous bigotry and xenophobia that pervaded the entire sequence of events. Here's how it all went down, and why it was even worse than most people realize today.

What happened to San Francisco in 1906?

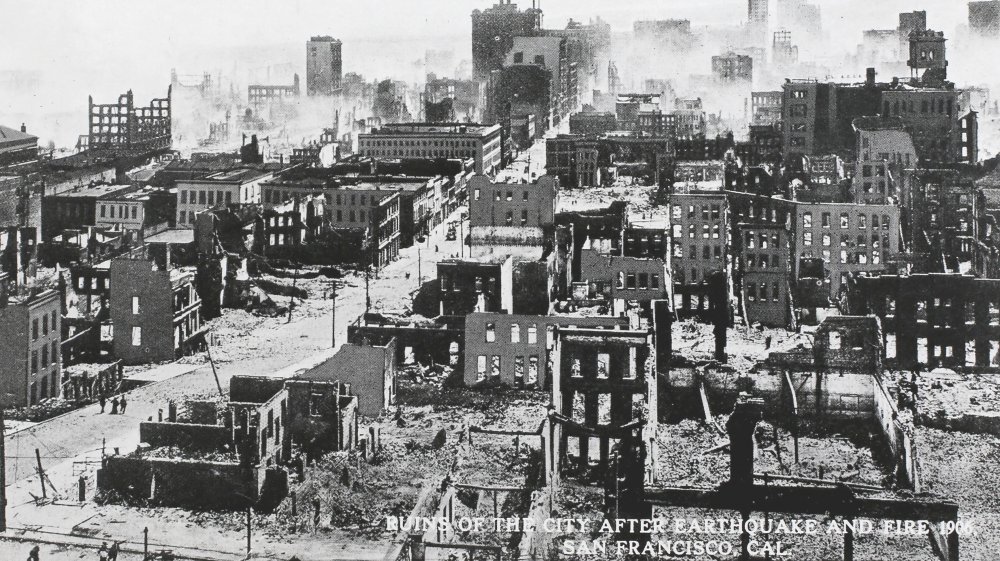

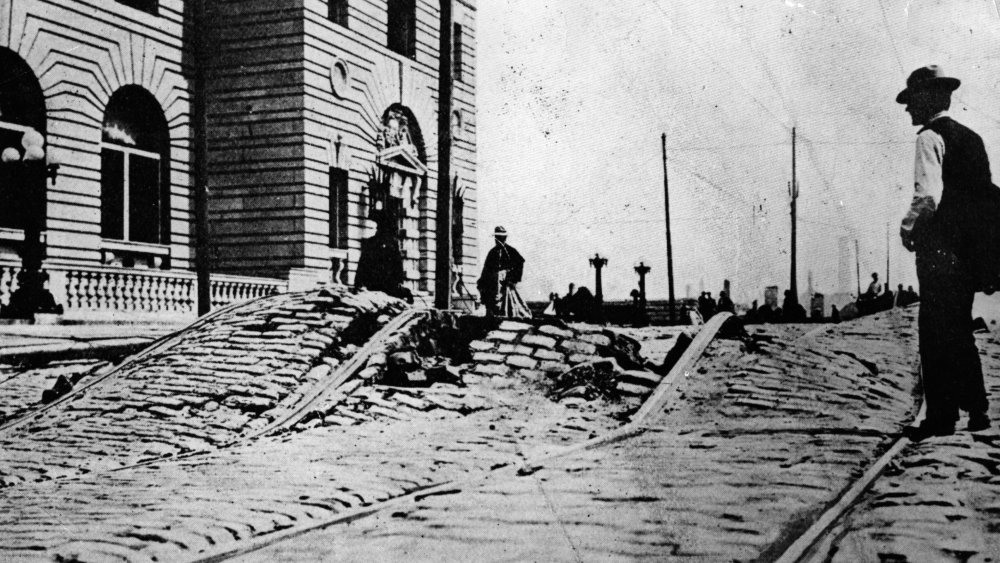

In the early morning of April 18th, 1906, as explained by History, a 275-mile segment of the San Andreas Fault slipped. Shock waves rippled from Los Angeles to Oregon, but in the general area of San Francisco, this manifested as a major earthquake with a magnitude of nearly 8.0 on the Richter scale. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the Golden City wasn't exactly a stranger to big earthquakes — they'd previously been hit in 1864, 1898, and 1900 — but nothing had prepared them for the devastating ferocity of the 1906 quake. The entire city shuddered, emitting what was described as a "roar of 10,000 lions," as City Hall caved in, the glass ceiling of Palace Hall shattered, the water mains were destroyed, and cable cars halted in their tracks. In a lack of foresight, much of San Francisco's architecture consisted of brick and wooden Victorian structures, and as the earthquake was followed by four days of fires, about 28,000 of these buildings would be destroyed. This incident basically demolished San Francisco, as it then existed, and led to an estimated $350 million in property loss, to say nothing of the thousands of corpses left in the disaster's wake.

That said, San Francisco wasn't the only city leveled by the quake. Entire neighborhoods of Santa Rosa were obliterated, as reported by the Press Democrat. San Jose was also hit quite heavily, according to Mercury News, as well as neighboring towns like Milpitas and Irvington.

The initial impact of the 1906 earthquake

The early moments of the earthquake were a terrifying harbinger of what was to come. One survivor claimed that "the air was filled with falling stones," according to Charles Morris, which crushed countless bystanders beneath them. Another survivor, Samuel Wolf — who at one point saved a woman from flying out an open window to the pavement 50 feet below — described seeing an entire building blow out, blinding and choking him with dust.

Buildings collapsed. People fell to their deaths, or were crushed by their dwellings. Wagons were carted through the streets, filled with broken and bloodied body parts. A 1906 edition of the New York Times reported on one fissure, hundreds of feet deep, that cracked the ground. Another fissure was said to have opened beneath a cow named Matilda, sending her spiraling into the earth, only to re-close over her, burying her alive. While this latter story was never confirmed for certain, and SFGate notes that there are some disputes regarding whether the account was legitimate, it was nonetheless claimed that the only part of Matilda that remained above the ground was her tail.

The 'official' death toll of the earthquake — and the deaths that weren't counted

For such an immense catastrophe, the official death toll of the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 seemed, for many years, weirdly small — only 478, according to the Los Angeles Times. Now, yes, 478 is a lot of people, but considering that the earthquake and its resulting firestorms destroyed about 90 percent of San Francisco's structures, it seems hard to believe that number. In the following decades, as more facts were unearthed, it became clear that this "official" count wasn't just a gross underestimation, but a stark example of racism and xenophobia in action.

When historian Gladys Cox Hansen sorted through all the yellowed, crusted documents of the past, she found that the actual death toll was, at absolute minimum, around 3,000, and the reason that many of those people were not counted was bigotry — namely, they were immigrants. From Chinese workers to Irish ones, these people were essentially erased from history, as part of a larger propaganda effort to make the damage look lesser than it was. In particular, no casualties were reported from San Francisco's former Chinatown district, which NPR estimates had housed a population of around 14,000 in densely-packed blocks. Anti-Chinese prejudice in San Francisco was a huge problem at that time, and these struggles would only continue after the earthquake had left its mark.

The earthquake spawned a raging inferno

As devastating as the earthquake itself was, the fires that it caused were colossally worse. San Francisco's closely-spaced wooden architecture was poorly prepared for such a disaster, and as History explains, the destruction of the city's water pipes meant that when the fires did break out, the firefighters were unable to use water to put them down. When the raging flames met raging winds, according to the Bancroft Library, the fires turned into firestorms.

When all was said and done, the firestorms were blamed for the majority of the damage. They had continued unabated for three days, even after the military got involved and tried to fight them with questionable tactics. It wasn't until April 21st, according to the National Park Service, when the fires finally came to an abrupt halt, right in the center of a block of wooden-framed houses. By this time, over five hundred city blocks — containing both businesses and homes — had burned to the ground.

The dynamite quandary

How do you fight a citywide fire without water? There's no easy solution. The army's decision to attempt to stop the flames with dynamite, though, has been a source of fierce debate for over a century, and is generally perceived as not having aged well.

The usual consensus, as pointed out by the Bancroft Library, is that the explosives — which were supposed to stagnate the flames, by creating a firewall — succeeded only at spreading them further. This choice had been made out of desperation, according to SFGate, and was performed by untrained crews, since the city's resident explosives expert, fire chief Dennis Sullivan, had been killed in the initial quake. The dynamite efforts swiftly became a fiasco, from using the wrong powder to a supervisor being drunk, and as the fires grew faster and hotter, both soldiers and firefighters were forced to flee. As was later written by author Jack London, a survivor of the catastrophe, "Dynamite was lavishly used, and many of San Francisco's proudest structures were crumbled by man himself into ruins, but there was no withstanding the onrush of the flames."

Terror on the streets of San Francisco, as a 'shoot-to-kill' order is put into effect

As if the situation wasn't deadly enough, once federal troops got involved, martial law was implemented. To prevent looting, Mayor Eugene Schmitz authorized an official "shoot-to-kill" order, allowing the use of deadly force against "any and all persons found engaged in Looting or in the Commission of Any Other Crime." The consequences of implementing this "shoot-to-kill" law — which, for one, the mayor was not legally allowed to order — were swift, violent, and even messier than expected. It certainly increased the death toll, but according to the Bancroft Library, it's unknown just how many people were shot, or under what circumstances, though the National Park Service estimates that there were anywhere from a dozen to a hundred instances. As for the unreported killings? They remain a mystery.

By day two, the Navy, Army, and National Guard were all occupying the burning city, alongside gangs of armed civilians, all of whom were trying to maintain "law and order" in their own contradictory ways. Reports of military misconduct were frequent, from the murder of presumed looters to unnecessary evacuations and/or closures, but the different factions generally passed the buck. The end result of all this, in any case, was more death and suffering, as no clear leadership emerged in the crisis.

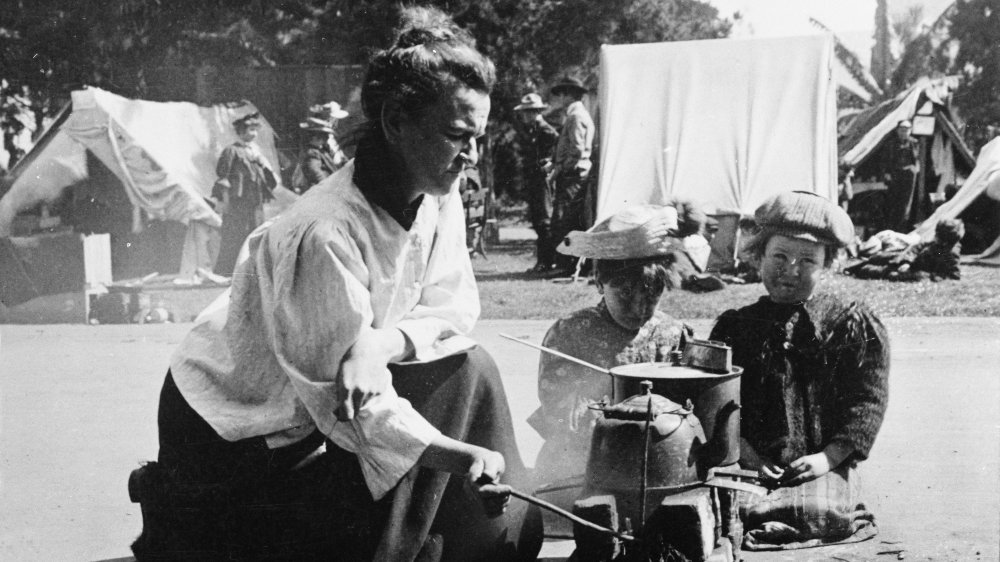

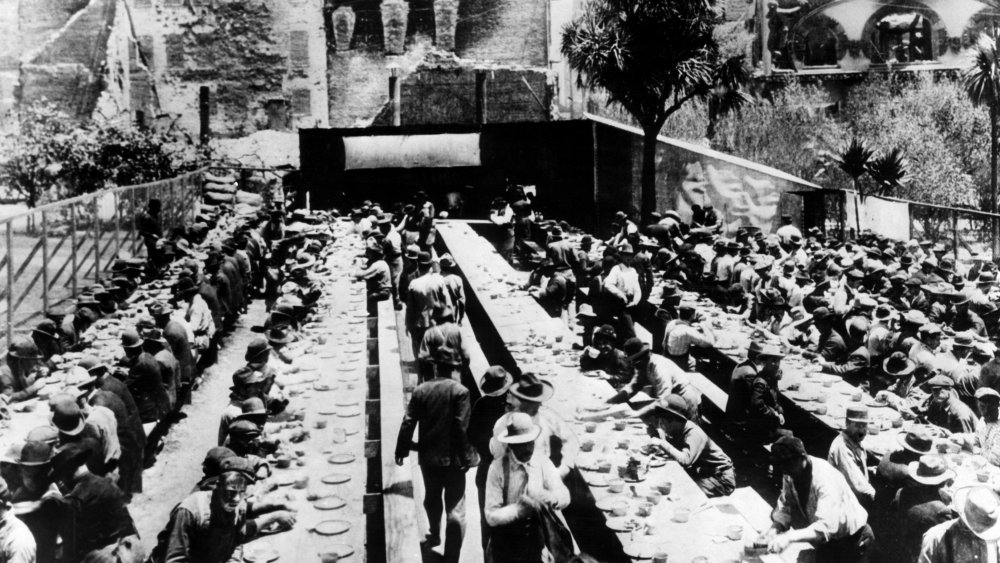

Refugee camps in Golden Gate Park

After the fires burned out, and the dust settled, hundreds of thousands of people were left homeless. While a vast swath of the population simply left San Francisco behind, at least 250,000 sought safety in Golden Gate Park, according to Atlas Obscura. Within that area, the survivors were assembled into makeshift refugee camps, carefully organized into grid-like formations of tents, where they lived day-to-day in the wake of the earthquake, not knowing what the future held. Regardless, people did the best they could to resume their old lives, using the dining hall for social gatherings, and bringing children together into playgroups. As described by the National Park Service, there grew to be 26 refugee camps filled with San Francisco's survivors, 21 of which were operated by the military. One of these camps, which held the refugees from Chinatown, was isolated from the others.

By the time winter was on the horizon, San Francisco had still not been entirely rebuilt, so a joint effort was made to build wooden cottages, colloquially referred to as "earthquake shacks," for the refugees to stay in during the cold weather. Mayor Schmitz, evidently, had some problems with this, once complaining, "I'm only afraid these people will never want to leave their new homes here," but the shacks were built, leased to refugees for only $2 a month, and provided a vital source of comfort and safety during this traumatic time.

The 1906 earthquake was a hard hit to science labs

People, animals, and architecture weren't the only things that the fire burned up. Scientific laboratories and studies, as well, faced irreversible damage.

Particularly major losses occurred to the California Academy of Sciences, which saw almost all of their collections burned to a crisp. Most of the specimens that survived were only due to the heroic actions of a young curator named Alice Eastwood, as explained by the Biodiversity Heritage Library, who assembled a small group of others, raced back into the Academy, and rescued 1,497 irreplaceable botanical samples. As the fire continued, Eastwood allowed her own possessions and home to go up in flames as she dedicated herself to preserving the specimens, carting them from place to place until the fires died down. This incident made Eastwood instantly famous, as written by Margaret W. Rossiter, though it's worth noting that it was only the opening chapter of a long and distinguished career, as she later boasted over 300 publications to her name. Eastwood died in 1953, at age 94, back home in San Francisco.

The earthquake and fires created an insurance disaster

When an entire city burns down to the ground, probably the last thing anyone wants to consider is tangling with insurance agents. Sadly, after everything that the citizens of San Francisco had been through, the insurance nightmare that followed was excruciatingly chaotic ... and, for the insurance companies themselves, one of their biggest losses in history. The problem for insurance companies was that while they didn't cover earthquake damage — disturbing, right? — they did cover fire damage, and most of the property loss was due to fire. According to the Insurance Information Institute, the catastrophe produced $235 million in insured losses, and only about $180 million of that was paid out. Any profit that the insurance industry had seen in the past 47 years was completely wiped out, and 14 insurance companies went kaput.

Even today, the earthquake gap in insurance continues to be a major factor. As MarketWatch points out, a vast number of Californians can't afford to add an "earthquake rider" onto their insurance plans, due to soaring deductibles, leaving them highly vulnerable if/when the next big quake hits.

Officials downplayed the calamity in San Francisco

Often, in the wake of a horrific disaster, leaders will deceptively downplay the true tragedy, consequences, and death toll, in order to get money rolling again. Think back to the mayor in Jaws, who keeps the beaches open despite shark attacks. And in real life, this same sort of public gaslighting happened following the 1906 earthquake, which the book Acts of God: The Unnatural History of Natural Disaster in America describes as "one of the great disinformation campaigns of turn-of-the-century America."

What happened? Essentially, a huge propaganda effort was made to downplay the role of seismic activity and insinuate that the real problem had been the fires. While technically true, as the fires did most of the damage, this framing purposely ignored the reality that the fires only happened because of the earthquake. Why the sneakiness? Because local business leaders were terrified that if San Francisco was perceived as potential earthquake territory (which it was), then nobody would invest in it commercially. So, once the fires were put out, Governor George Pardee immediately tried to move on, stating that, "The City by the Golden Gate will be speedily rebuilt, and will, almost before we know it, resume her former great activity," according to San Francisco History. Meanwhile, though a report on how to build earthquake resistant structures had been prepared by a committee, local leaders shut it down. The very real dangers of seismic activity were kept hush-hush.

The rebuilding of San Francisco ... and the racism that accompanied it

The San Francisco that rose from the ashes would be an entirely different city from the one that came before, both literally and in spirit. By the latter half of the twentieth century, this all-new, all-different San Francisco would grow to become a haven for progressive social movements, most prominently seen in the city's long history of advocacy for the LGBTQ+ community.

Back then, though, the process of building the new San Francisco still involved many of the same problems as the old version. For one, building the city back up so quickly took a toll on the local environment, according to the Oakland Museum of California, as nearby redwood forests were chopped down to stumps. Furthermore, existing racist tensions came to the forefront, as explained by SFGate, since the powers-that-be wanted to gentrify the remainders of Chinatown, and push the existing Chinese population out to the new city's fringes. According to the New York Times, one group, the so-called Asiatic Exclusion League, even issued the following statement: "We can withstand the earthquake. We can survive the fire. But the moment the Golden State is subjected to an unlimited Asiatic coolie invasion there will be no more California."

The local Chinese population fought back, teaming with the Chinese government to exert economic pressure on the San Francisco government. As a result, the residents of the old Chinatown got to keep their home, and rebuild in place.

The 1906 earthquake changed the course of California history

Before the earthquake, San Francisco was the unofficial capital of the West Coast of the United States, particularly in regard to trade and economics. The city's destruction in 1906, as explained by the nonprofit organization SF-Info.org, forever changed that.

Even though San Francisco was rebuilt at a stunning speed, the overall impression soon became that it was a risky city to do business in — because of the hovering possibility of another earthquake — and so commercial industries, trade, and immigration all pivoted south to the "safer" location of Los Angeles. This particularly included a large influx of new immigrants from Japan, according to Jesse O. McKee's Ethnicity in Contemporary America. Now, over the ensuing century, the notion of Southern California somehow being less of an earthquake risk than the northern parts has been clearly demonstrated as ludicrous. Back then, though, this concept led to a population boom in Los Angeles, thereby propelling it forward into the L.A. you know and love today. Thus, it's worth pondering: If the 1906 earthquake hadn't happened, how different might the state of California have turned out, in the long run?

The incident marked the turning point of today's earthquake science

If there was one unambiguously positive result that came from the devastation that the 1906 earthquake wrought on San Francisco, it was that the whole thing served as a major wake-up call for the field of earthquake science.

Earthquake research in the U.S. had been stagnating before 1906, as explained by the United States Geological Survey (USGS), and scientists were generally unaware of what caused earthquakes, how and why they happened, or other key details that the world takes for granted today. When the big quake hit San Francisco, that changed in a heartbeat, as scientists from across the state of California came together to study the damage, assess the risks, and learn more. Mere days after the incident, a State Earthquake Investigation Commission was assembled by the governor, spearheaded by Professor Andrew C. Lawson, a geologist from the University of California, Berkeley. This was the first government-organized, scientific earthquake investigation in the United States, and within two years, they produced a much-vaunted report which USGS still credits as having formed the blueprint of what is now known about earthquakes in California today.

While earthquakes continue to happen — the so-called "Northridge earthquake" that hit Southern California in 1994 was particularly destructive, as explained by the Associated Press — knowledge is power, and as scientists continue to study and learn more about earthquakes, more work can also be done to prevent and/or mitigate their damage, according to USGS.