The Untold Truth Of Valhalla

Of the numerous mythologies and legends found throughout the history of the world, few are as metal as the stories of the old Norse, whose gods were basically just Vikings-plus, larger-than-life warriors with magic hammers and boats made of dead people's fingernails and what have you. And of all locations within the Norse cosmology, perhaps the most glorious and desirable is the great hall of Valhalla, the feasting place of the allfather Odin, where he drank and did battle with the spirits of the greatest warriors who ever lived and died.

But Valhalla is more than just Viking heaven, and it's far from the only Norse afterlife. So if you're shopping around for an eternal resting place for your soul, here are some facts about Valhalla to help you decide if it's right for you. Sure, the prestige of it is hard to beat, but is it worth the price?

What does "Valhalla" mean?

The name "Valhalla" evokes a glorious image of an afterlife for the mighty, and its meaning is equally glorious in its simplicity. "Valhalla" is a Latinization of the Old Norse "Valhöll," which, according to the Online Etymology Dictionary, means "hall of the battle-slain," which is ... what Valhalla is. The first element of the word, "valr," is the term for those slain in battle and can also be seen as the first part of the word "valkyrie," who are the choosers of the slain. The word "valr" also shares an ancestor with the Latin word "vulnus," meaning "wound," the source of the English word "vulnerable."

While it doesn't take an etymological genius to recognize that the "höll" or "halla" portion of the name is pretty directly related to the English word "hall," with which it shares a meaning, the two words share another relative that is both fitting and surprising. The ultimate source for these words is the Proto-Indo-European root "kel-," which means "cover" or "hide" and which gives us such English words as "conceal," "cellar," "helmet," and "hole." It's also responsible for "apocalypse," which only makes sense if you remember that word literally means an unveiling or, you know, a revelation. Anyway, "hall" and "höll" are both related to another word for a covered, hidden place, which, like Valhalla, is also an abode of the dead: Hell, or as the Norse called it, Hel.

Who goes to Valhalla?

While it may be true that all dogs go to Heaven, it was not the case that all humans went to Valhalla. Similar to the Greco-Roman conception of the Isles of the Blessed, Valhalla was the final destination for those who had distinguished themselves in valor and virtue. And for the Vikings, there was no virtue greater than an honorable death in battle. The ones who distinguished themselves enough in valorous death to reside in Odin's great hall were known as the "einherjar," which means "lone-fighters" or even "army of one." According to Encyclopedia Mythica, these champions are adopted as sons by Odin, who, in his aspect as a gatherer of fallen warriors, is known as the Father of the Slain.

The residents of Valhalla were chosen by the valkyries and carried up (or possibly down, depending on the source) to Odin's great hall. Once there, they spent their days eating and drinking their fill. Specifically, they feasted upon a magical boar named Sæhrímnir, which regenerated every night so they could eat it again the next day. Even though the number of the righteous dead is huge and ever-increasing, the meat never runs out, nor does the mead ever run dry. It's not all feasting, though: The einherjar spend most of their time in battle, training for the events of Ragnarok.

The role of the valkyries

Besides having a song named after them that's appropriate for launching a fleet of helicopters and being the name of Tessa Thompson's character in the Thor movies, what exactly is a valkyrie? According to Encyclopedia Britannica, valkyries are a group of maidens in the service of Odin whose main role is to survey the fallen on the battlefield and decide which ones were deserving of a place in Valhalla. Suitably, then, the word "valkyrie" means "chooser of the slain." These shield-maidens of Odin were known to be both beautiful and terrible, as they were ethereal young women clad in full battle armor and riding through the skies with flashing shields and helmets, whose presence foretold the coming of battle, death, and bloodshed. They could protect the lives, armies, and ships of those warriors who found their favor, but they could also cause the immediate death of those who displeased them.

While their role as noble yet sinister battle maidens belies the sort of traditional gender roles you might expect from ancient societies, don't worry: There's still a context in which they are made subservient to men. After their primary job of selecting the souls of those destined to join Odin's einherjar, their secondary role in Valhalla is to spend all day bringing the dead warriors magic mead and immortal pig meat.

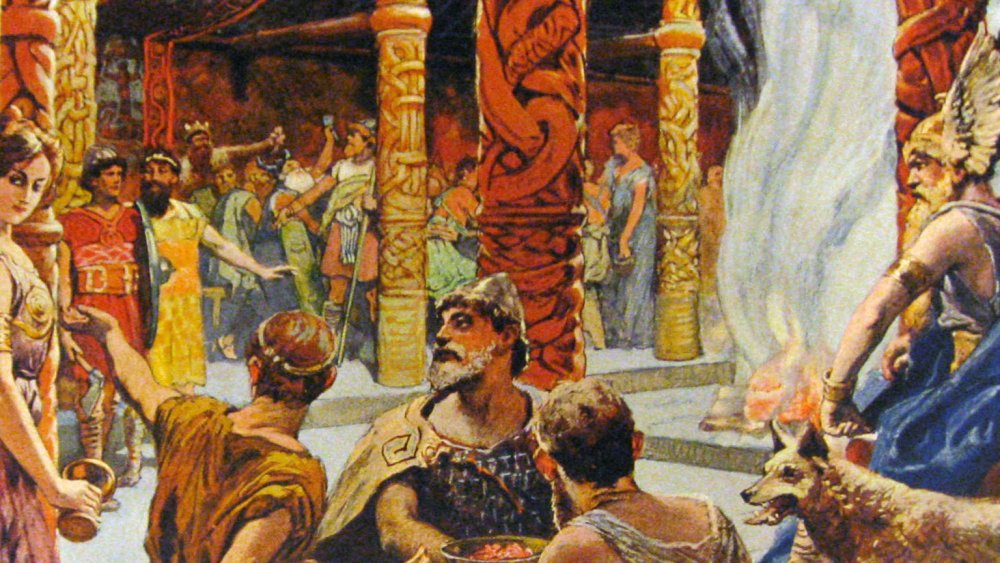

What does Valhalla look like?

You might assume that a feasting hall for the immortal souls of the mightiest warriors who ever lived would probably be pretty metal, and you'd be right in that assumption. Various works of Norse mythology include descriptions of what Valhalla looks like, and together, they help give us a pretty good picture of Odin's great hall. Norse Mythology for Smart People explains that Valhalla is described as "gold-bright" due to its roof being covered in shining golden shields, which line the top of the hall like shingles. The interior of the hall is full of many feasting tables for the einherjar, and the great chairs surrounding these tables are forged from breastplates. The rafters are made of spear-shafts, and the benches are all covered with coats of mail. The creaking of these numerous benches under the weight of warriors and gods was said to create a sound like thunder. The numerous gates of Valhalla are guarded by wolves, while eagles soar above it.

Outside the front door of Valhalla stands the great tree Glasir, whose leaves are all a reddish gold. (Maybe rose gold? Are iPhones made from the foliage of Valhalla?) The tree was said to be "the fairest known among gods and men," and the beauty of gold was so associated with it that several poems use the terms "leaves of Glasir" or "needles of Glasir" as a metaphor for the precious substance.

Where is Valhalla?

How do you get to Valhalla? Well, obviously you redden your gore-drenched sword with the blood of many foreign lands, like Eric Bloodaxe in the saga Fagrskinna. But, like, what if you wanted to go there without dying and being airlifted there by a valkyrie? Is that possible? According to various Norse sagas where various heroes just kind of walk there, it is. Norse Mythology for Smart People says that the most famous depictions of Valhalla speak of it being within the realm of the Norse sky gods, Asgard. It makes sense that Odin's hall, where the gods feast and the blessed heroes rehearse for doomsday, would be within the shining celestial fortress of the aesir.

But that's not always strictly the case. The firm distinction between Valhalla as an eternal reward for the valorous and Hel as the afterlife for those who died ignominious deaths from, say, old age or a weird accident with an immersion blender was not one that was drawn by the Vikings themselves. This dichotomy was likely instituted by Snorri Sturluson, a medieval scholar probably adding some Christianity to his old Norse paganism. As such, it's not uncommon to find a source stating that Valhalla is in the underworld. Due to the Scandinavian practice of burial mounds, the interiors of rocks and hills were seen as the abode of the spirits of the dead. Why should Valhalla be an exception?

The goat and the deer on top of Valhalla

Battling hordes of ghost vikings, feasting crowds of gods, and bustling crews of valkyries aren't the only inhabitants of Valhalla. Besides the wolves hanging over the gates and the eagles soaring among the rafters, there are other magical creatures who reside at the great hall of the fallen and actually contribute something more than just a painting-on-the-side-of-a-van aesthetic. According to Encyclopedia Mythica, the roof of Valhalla is the home of two different miraculous animals. The first of these is the great stag Eikþyrnir, whose name means "oak-thorny." All day, this great horned beast stands on the shield-plated roof of Valhalla eating from the magical tree Læraðr, which is not to be confused with Glasir, the other magical tree that stands next to Valhalla. While some authors identify Læraðr with Yggdrasil, the great ash tree upon whose branches the nine realms hang, this tree seems to exist merely as food for a magical deer. As Eikþyrnir nibbles these magical branches, his horns begin to sweat drops of water, which fill the well Hvergelmir, from which all rivers are fed.

The other roof animal of Valhalla is the she-goat Heiðrún. She also grazes from the branches of Læraðr, and her udders produce not milk but the very mead that the valkyries serve to the einherjar in unlimited quantity. Every day, Heiðrún is said to fill a barrel with enough mead to get every warrior in Valhalla drunk.

Valhalla is a big, big house with lots and lots of rooms

The mythological poem Grimnismal contains one of the most thorough descriptions of Valhalla, from the lips of Odin himself in disguise as a man named Grimnir, one of his many aliases. In this account, Valhalla is said to be within a realm in Asgard known as Glaðsheimr ("bright home"), stretching wide over the landscape. Stanza 22 says that Valhalla stands behind the sacred gate Valgrind, which opens beyond Valhalla's 540 doors, each of which is large enough for 800 einherjar to charge through at once. In addition to having 540 doors, the poem says that Valhalla has 540 halls, the greatest of which is Thor's great hall, which itself has 540 rooms.

This part of the poem may be something of a confusion on the poet's part (understandable with how many "540"s are being thrown around), because most sources do not consider Thor's hall to be part of Valhalla. Thor's hall, which Odin calls the greatest home he has ever seen, is called Bilskírnir (which might mean "everlasting" or "lightning-crack") and is usually said to be in the realm of Asgard called Þrúðvangr or Þrúðheimr, which was Thor's allotment when Odin divided up his kingdom. Wherever it's located, inside Valhalla or not even in the same realm as Valhalla, Bilskírnir is where Thor lives with his wife Sif and their children, with apparently hundreds of empty rooms left over.

Valhalla isn't all just fun and magic goat's milk

While it might seem like the hordes of eternal warriors spend their time in Valhalla eating magic pig meat and getting drunk on magic goat-udder honey wine served by gigantic warrior women, the fact is that the einherjar find themselves in Odin's hall for a very serious reason. As Norse Mythology for Smart People explains, the drinking and feasting is just their nighttime activity. The einherjar actually spend their entire day fighting each other and doing valorous deeds. Those warriors who find themselves injured or killed (double killed?) during these postmortem skirmishes will be miraculously restored to health each night, just like the giant pig they eat every day.

Even though killing all day and drinking all night might have been a Viking's idea of Heaven, the einherjar aren't just having fun. They're actually training for the most important battle of their afterlives: Ragnarok. This apocalyptic battle between the gods and giants will see Odin fight against the dread wolf Fenrir after the enormous beast breaks free from where he was imprisoned to keep him from literally eating the world. The einherjar will stream through the 540 doors of Valhalla, 800 men at a time, and through the sacred gate Valgrind to fight at Odin's side. Unfortunately, despite their training and valiant efforts, Odin and his Large Adult Battle Sons are fated to lose and die along with the rest of the universe.

Gylfi goes to Valhalla (or does he?)

A number of mythological texts describe Valhalla as a place you could kind of just ... go to, such as you might go to Target or Chuck E. Cheese. This is largely made possible through the fact that a number of Norse sagas and poems were euhemerized, meaning that Asgard was interpreted not as a celestial abode for gods but as an earthly kingdom, and Odin and his aesir were thought of not as gods but just really powerful kings who might have had magic powers. One such notable account of Valhalla comes from Gylfaginning ("The Beguiling of Gylfi"), a 13th-century prose account by Snorri Sturluson.

In this story, a king named Gylfi is convinced that the gods are just magicians accomplishing their will through illusions. To test this, he disguises himself as an old man named Gangleri and goes to visit Asgard. The aesir, through their magic, have foreseen his visit and so prepare a whole host of illusions. It is due to this magic that he sees a miraculously large hall with gold shield shingles (i.e., Valhalla), inside of which he sees a man juggling seven swords at once. There, he finds three thrones, on which sit three kings — High, Just-As-High, and Third (all of whom are Odin in disguise) — with whom he engages in a riddle contest through which the secrets of Valhalla are revealed.

The other hall of the slain

While obviously not every Nordic person who died went to Valhalla, not even every valorous warrior who died in the throes of battle was guaranteed to make it there, either. When the valkyries perused the blood-soaked fields of the slain, they only took about 50 percent of the dead with them to Valhalla. The other half made their way to Folkvangr, the realm of the goddess Freya. As Ancient Origins explains, Freya was one of the most prominent goddesses in the ancient Norse religion, but she was one of the Vanir, who were kind of the earthier, fertility-based counterparts to the more ethereal sky gods of Asgard. Her realm was Folkvangr, the other home for fallen warriors.

"Folkvangr" means "field of the people" or "field of the warriors," which leads some people to speculate that the real distinction between Valhalla and Folkvangr is that Valhalla is the abode of the leaders or officers of the various armies, while Folkvangr is the destination for the ordinary warriors (which seems like it wouldn't break down to a 50/50 split, but myth doesn't always consider such bits of realism). Freya's meadow also contains a great hall (Sessrumnir, "room filled with seats") but might distinguish itself from Valhalla by also allowing the souls of women who died noble deaths, as implied in the story of the handmaiden Thorgerdr in Egil's Saga.

The afterlife for civilians

So, if the battlefield elite go to Valhalla to prepare to get wolfed to death with Odin, and the common soldiers and maybe women go to Folkvangr with Freya, what happens to everyone else? Well, Norse mythology contains a number of possible afterlives, which aren't always consistent across various sources. The most common afterlife for the majority of humans, according to Norse Mythology for Smart People, is Hel, ruled by the goddess also called Hel (sometimes Hela), which, despite the name being related to the English word "Hell," is not a realm of punishment. It's just the regular afterlife where most people go and then eat and drink and fight and bone and do whatever Vikings did when they were alive, just as ghosts now. Some sources say that Valhalla is just a part of Hel, so there is no clear moral association with the realm.

While the lines between the various realms of the dead were usually pretty blurred, there is one old Norse source that describes an afterlife that is specifically meant for punishment. That place is called Nastrond, which has floors covered in snakes and ceilings dripping with poison. That said, the source that talks about Nastrond was almost certainly influenced by Christian conceptions of Hell. Almost as obscure is the idea that sailors and other seafarers who died at sea were dragged down by the giantess Ran ("robber") to populate her watery realm.

The real-life Valhalla

When years of myth and legend proclaim a most glorious hall that serves as the eternal (well, semi-eternal) home of the greatest and most illustrious men who have ever lived, it's only natural that someone would eventually try to recreate it on Earth. Well, the good news is that if you, like Gyfli, want to go visit Valhalla, it's as simple as making a visit to Germany's Danube Valley. Just outside of Regensburg in Bavaria stands the Walhalla monument, a popular tourist destination.

Just as Valhalla is the resting place of fallen warriors in Germanic myth, the Walhalla (pronounced the same because w's are like v's in German) was built by neoclassicist architect Leo von Klenze under the orders of King Ludwig I in 1830 to serve as a memorial for notable figures of German history. The monument was finished in 1842 and, in the neoclassicist style popular at the time, mimics the look of the Parthenon in Greece rather than attempting to mirror any of the descriptions of Valhalla in the Norse sagas. Inside are 130 busts and 65 memorial tablets (with new busts being added continually since 1962) dedicated to the memory of historic Germans and other German-speakers such as Arnulph I, Duke of Bavaria, with whom you are doubtlessly already familiar. Part hall of fame and part history museum, this earthly Valhalla seems a worthy — if considerably less boisterous — successor to its heavenly counterpart.