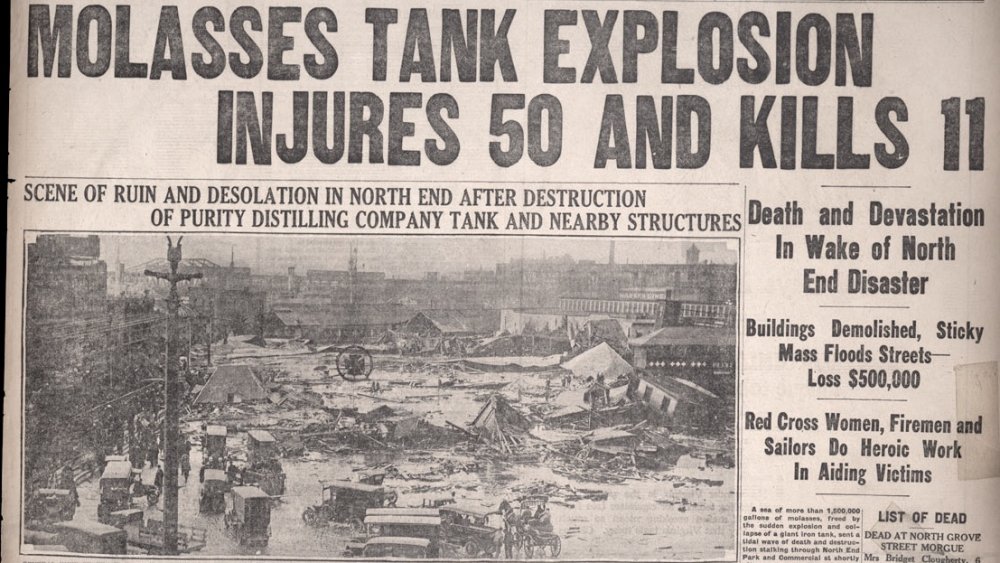

The Great Molasses Flood Was Worse Than You Thought

It almost sounds like a sweet dream come true: 26 million pounds of molasses held in a storage tank tall enough to tower over a 2-story house. Built in Boston's North End neighborhood in 1915, the massive vat stood 50 feet tall, stretched 90 feet across, and literally dripped with 2.3 million gallons of sugary, gooey goodness, according to History. The molasses was first fermented for industrial purposes and later repurposed to produce booze, per Mass Moments. But on January 15, 1919, the titanic structure ruptured, causing the calamity known as the "Great Molasses Flood" or the "Boston Molassacre."

The saying "slow as molasses in January" might lead you to believe that a lazy wave of molasses trudged sluggishly along the streets of Boston in January 1919. You might even picture a sticky situation that could easily be resolved with a ginormous stack of pancakes and a few hundred hungry people. If so, you wouldn't be the first person to take the incident lightly. Gavin Kleespies of the Massachusetts Historical Society said the Great Molasses Flood is "misremembered [as] something out of Willy Wonka." In reality, it was a deeply traumatic ordeal defined by abject negligence, desolation, and senseless death.

A money-hungry company built an obviously shoddy storage tank

The story of the Great Molasses Flood begins with the Great War and ends with a depressing lesson in unconscionable greed and shocking incompetence. The U.S. Census Bureau explains that the storage tank for the molasses was hastily constructed by United States Industrial Alcohol (USIA) to help keep Europe's bombs and munitions businesses booming during WWI. USIA's subsidiary, Purity Distilling Company, was tapped to ferment molasses to make industrial alcohol, a key element in the manufacturing of dynamite, ammo, and artillery shells. Per Boston public radio station WBUR, after the war there was a push to convert the molasses into rum before Prohibition kicked in.

Amid its initial sugar-rush to capitalize on wartime contracts, USIA effectively built a sticky ticking time bomb. As History details, the vat's metal walls were obviously way too thin to accommodate the 2.3 million gallons of molasses that were added two days before the flood. A competent engineer would have seen this, but according to Mass Moments, the person who supervised the construction of the tank couldn't read a blueprint, and no architects or engineers inspected it. There was no attempt to test its durability before operations commenced. There was also an unseen flaw: the metal was sorely lacking in manganese, making it brittle when temperatures dipped below 59 degrees Fahrenheit. On the day of the disaster, it was 40 degrees outside.

Leaking molasses was hidden with paint

The only thing more glaringly obvious than the molasses tank's lack of structural integrity was the moral bankruptcy of the company that rushed to construct it. From the get-go, United States Industrial Alcohol received and ignored enormous warning signs of the looming disaster. Mass Moments says the vat vibrated as it strained to sustain millions of pounds of molasses. Fissures formed at the rivets, via History, and the tank noticeably groaned all 29 times it was filled despite the fact that the load only approached full capacity four times. (The fourth and final time was two days before the flood).

The tank wasn't just in poor shape — it was porous and frequently leaked. In a 2015 analysis, civil engineer and professor emeritus at Southern Illinois University in Edwardsville Dr. Mark Rossow notes that Boston's 50-foot-tall red flag was originally steel-blue. But USIA later painted it brownish-red in a blatant attempt to mask the hemorrhaging molasses. In a stunning display of indifference, the USIA treasurer's office dismissed physical evidence that the tank was deteriorating. A concerned worker showed up with shards of metal that had fallen from the walls of the buckling structure, only to find himself pleading with a brick wall. The response he got was: "I don't know what you want me to do. The tank still stands."

The tank was placed in a neighborhood of poor, mostly Italian immigrants

United States Industrial Alcohol's cavalier attitude toward safety may have been magnified by societal attitudes toward the residents of Boston's North End. The Massachusetts Historical Society's program director, Gavin Kleespies, explained to Atlas Obscura that in the early 19th century, North End was home to "a high percentage of noncitizen immigrants who didn't have political muscle. That's part of why this dangerous [tank] ended up near them." Plus, much to the chagrin of many citizens, the immigrants mostly hailed from Italy.

A whiny excerpt from a 1906 guidebook about Boston written by Samuel Adams Drake provides a sense of the intense animosity felt toward Italians living in North End: "Nowhere in Boston has Father Time wrought such ruthless changes, as in this once highly respectable quarter, now swarming with Italians in every dirty nook." Drake went on to lament that those who oppose the Italian presence no longer "feel at home at all."

It's probably not an unsafe bet that blaring alarm bells fell on deaf ears at least partly because the tank mainly endangered these perceived dregs of society. Per Mass Moments many of the unwanted residents of this densely packed neighborhood were out having lunch and enjoying the unseasonably warm weather (yes, 40 degrees in January is unseasonably warm in Boston) when the rickety molasses dam burst without warning.

Fast as molasses in January

Under normal circumstances, molasses seems deliberately slow. As History points out, the liquid is 50 percent denser than water and thickens in the cold — hence the expression, "slow as molasses in January." However, Harvard University researcher Nicole Sharp, who learned that figure of speech in her native Arkansas, told the Associated Press that the "molasses wasn't slow" when it flowed on that fateful January day in Boston. The tank had just been refilled two days prior to its collapse, so the molasses was much warmer than its surroundings.

Sharp and her research team determined that the molasses could have traveled as fast as 35 miles per hour, devouring the surrounding North End neighborhood like a 26 million-pound mudslide. The resulting wave reached 25 feet high, according to some accounts. The U.S. Census Bureau says that the wave measured 40 feet high and "toppled telephone poles, snapped the supports of a nearby elevated railway, and knocked a firehouse from its foundation." Entire homes collapsed like houses of cards.

Citing contemporary press coverage, Boston.com reports that the molasses decimated six buildings and tossed cars into lamp posts. New England Today tells of a five-ton Mack truck that the molasses lifted and crashed it into a building. In minutes, the wave left a path of absolute carnage that spanned half a mile.

Death by molasses was anything but sweet

There was no time to brace for the molasses flash flood that ambushed Boston's North End. Per Boston.com, contemporaneous reports and eyewitness descriptions depict an all-destroying, all-conquering wave from which "there was no escape." It swallowed men and horses whole and buried others under rubble. In total, the flood claimed 21 lives and injured 150 others.

George Layhe had been an exemplary fireman before his life was extinguished by the flood. First responders spent hours trying to wrest him from the wreckage of a partially collapsed fire station, but the U.S. Census Bureau writes that Layhe drowned in molasses. Laborer Patrick Breen got dumped into Boston Harbor by the syrupy onslaught and later died from pneumonia and internal injuries. Others suffered fractured skulls and limbs from the crushing impact of falling debris or after molasses smashed them into hard surfaces.

Most people and animals that perished found themselves glued in place and struggling to breath as viscous molasses clogged their airways. The sugary liquid thickened even more as the evening brought colder temperatures, says History. Victims did not go gently into that cold, dark night. In Dark Tide: the Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919, author Stephen Puelo shares a harrowing account by a Boston Post reporter: "Horses died like so many flies on sticky fly-paper. The more they struggled, the deeper in the mess they were ensnared. Human beings — men and women — suffered likewise." Many eventually suffocated.

Children were killed by the molasses they used to eat

In 1919, molasses was a sweet tooth's poison of choice in the United States, topping table sugar as the nation's favorite sweetener due to its affordability before WWI, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The leaky tank of molasses in North End basically created a syrupy free-for-all. Children treated the tank like an inanimate candy man. But as Stephen Puelo describes in Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919, three youngsters who once gladly gathered molasses by the pailful would be engulfed in a sea of it.

Quoting Puelo's work, Boston.com recounts how 10-year-old Pasquale Iantosca completely vanished in molasses as his horrified father, Giuseppe, watched from their apartment window. The boy had been collecting firewood near the storage tank during his school lunch break. Giuseppe spent hours searching for Pasquale but returned home alone. A week later, the Boston Globe reported that the body of a boy recovered from the ravages of the flood was identified as Giuseppe's missing son.

Ten-year-old Maria Di Stasio was collecting firewood with Pasquale when the tank gave way. Workers reportedly found her "buried beneath a pile of molasses barrels near the base of the wrecked tank" a day later. Her brother, Antonio, tried to outrun the flood, but the sticky liquid trapped his ankles. He survived, but History reports that the molasses slammed him into a lamp post, seriously injuring his head.

Molasses turned the rescue effort into a messy nightmare

The violent deluge of molasses subsided within minutes, says Boston.com, and History writes that first responders arrived mere minutes after that. But their rapid reaction slowed to a crawl as plunging January temperatures caused the syrup to thicken around victims and make the already sticky streets harder to navigate. Dr. Nicole Sharp of Harvard told NBC that the increased viscosity caused problems for moving rubble. Firefighters had to place ladders over the molasses to avoid getting stuck in it themselves.

Rescuers spent hours arduously trying to remove rubble. And the molasses layer was so thick that it complicated the process of locating and identifying victims. History quotes the Boston Post's description of the victim's dire plight: "Here and there struggled a form — whether it was animal or human being was impossible to tell. Only an upheaval, a thrashing about in the sticky mass, showed where any life was." The Post also reported that people extracted from the molasses — a process that could take hours — and brought to the hospital were typically so thickly coated in gluey sweetness that one couldn't discern their age and gender. Families, sick with grief, inundated the hospital, often becoming delirious with worry. Many of the dead weren't recovered until days later.

The last Great Molasses Flood death happened at a mental asylum

Stephen Clougherty, the 21st and final fatality of the Great Molasses Flood, was at home with his mother, Bridget, sister, Teresa, and older brother, Martin, when the force generated by the rupturing tank ripped their house out of ground and sent it careening into the elevated railway. The resulting wreckage crushed Bridget to death, according to Boston.com.

Martin was jarred out of his sleep by the surreal scene playing out at his dislodged house. He told the Boston Globe that he knew "something unusual had happened [when he] awoke in several feet of molasses." As History details, Martin almost drowned but had the wherewithal to use his bed frame as a buoy. Using a makeshift boat, he managed to rescue his sister. But there was ultimately no saving Stephen, who didn't drown in molasses but remained immersed in it for the rest of his life.

Stephen Puelo points out in Dark Tide that Stephen Clougherty was also mentally challenged. Unable to cope with overwhelming trauma, Martin's once-docile little brother dramatically changed. He began having hallucination and violent eruptions. He became terrified of being stifled by molasses or crushed by a building. Inconsolable and uncontrollable, he was placed in a mental institution by his brother, who had reached his wits' end. Stephen's health continued to decline, and he contracted tuberculosis. He died shortly before Christmas.

Suffering families waited years for compensation

In a Guardian article published nearly 100 years to the day since Boston's infamous molassacre, writer Stephen Puelo remarked that the catastrophe impacted standards for constructing buildings in the same way that Boston's Cocoanut Grove nightclub fire ignited nationwide changes in fire safety requirements. The city's hazardous molasses tank "didn't even require a permit to be built," according to Puelo. But what United States Industrial Alcohol did to the residents of North End was impermissible.

Puelo notes in Dark Tide: the Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 that most of the families that lost someone lost the person who brought home the bacon, leaving grieving wives and children with few avenues to put food on the table. Many injured survivors were too hurt to work and spent months with little or no income. Some never worked again.

In addition to stricter regulations, USIA needed a hard kick in the bottom line. A total of 119 plaintiffs played David to USIA's Goliath in a class-action clash for the ages. But the lawsuit took ages to resolve. In 1925, after a five-year legal battle, a state auditor sided with the plaintiffs and awarded $628,000 to the families. However, the payout came with a catch. Puelo told Boston Magazine that families whose loved ones suffered more before death received higher compensation.

USIA tried to blame anarchists for the Great Molasses Flood

United States Industrial Alcohol had partly benefited from anti-Italian prejudice when it callously placed a faulty tank in North End, per Atlas Obscura. And when the time came to be held accountable for upending residents' lives and robbing families of their loved ones, USIA would try to capitalize on similar tension. As told by Mass Moments, Boston's Italian immigrant community had become a haven for a handful of the anarchists who had orchestrated bombings throughout New England and New York, some of which specifically targeted USIA facilities in the past decade. In the previous year, 40 explosions had rocked Boston and surrounding locales.

In the immediate aftermath of the Great Molasses Flood, newspapers had erroneously asserted that the tank exploded, providing USIA with useful ammo. It crafted a narrative that positioned the company as the victim of anarchists who wanted to tank the company's soaring profits by exploding the tank. History writes that over the course of the trial, roughly 1,000 witnesses testified, and 1,500 pieces of evidence were submitted. Flood survivors, USIA employees, and explosives experts weighed in. The weight of the evidence handily flattened USIA's weak defense.

An arduous and costly recovery

As the U.S. Census Bureau describes, it took an estimated 87,000 worker hours to clean up a mess that only took moments to make. The remnants of the 2.3 million gallons of molasses that roared through North End seemed to have no end in sight. It stuck to streets, trains, houses, horses, and humans. In a Boston.com interview, writer Stephen Puelo added that molasses pooled in people's basements and had to be blasted with hydraulic pumps in a "painstaking" undertaking. Some residents alleged that the sweet stink of molasses lingered for years after what ended up being a six-month cleanup.

That says nothing of the obliterated buildings, displaced vehicles, and downed telephone poles. The value of the property damage topped $100 million in modern dollars, according to Mass Moments. There may have also been steep environmental costs. The saltwater of Boston Harbor was used to clean the streets, turning the harbor brown for months. But what was the impact of all that surgery fluid? No such assessment was made in 1919, but WBUR observes that a 2013 molasses spill in Honolulu Harbor (pictured) fueled a buildup of bacteria that consumed oxygen and killed the local fish. And as oceanography Grieg Steward highlighted, Honolulu's molasses disaster was about 10 times smaller than Boston's.

Boston had already been ravaged by the 1918 flu pandemic

From the lead-up through the aftermath of the Great Molasses Flood, timing was everything, and nearly everything about that timing was terrible.

The molasses sat in the storage tank for only two days before the calamitous collapse, keeping the viscous liquid warm enough to move with lethal speed. As highlighted by History and Mass Moments, the vat was filled practically to capacity right before the temperature got cold enough to make the manganese-deficient metal brittle enough to break while the weather nonetheless remained mild enough for people to go outside, where they would find themselves at the mercy of a violent, stifling deluge of molasses. But as Harvard University researchers explained to the Associated Press, if the accident had just happened in summer instead of winter, the molasses likely wouldn't have thickened enough to impede rescue efforts. Few — if any — people would have died.

On top of all that, there's a possibly less obvious sense in which time conspired against Boston North End. As Stephen Puelo details in The Boston Italians, the 1918 flu pandemic ravaged many families in North End and East Boston. What began as embers of illness in August 1918 became a respiratory inferno that burned through Boston from October onward. Still reeling on the heels of an influenza wave that killed 5,000 Bostonians by the end of the year, per WGBH News, North End would be immediately flooded by another lethal wave, this time made of molasses.