The Truth About San Francisco's Black Plague Scare

It could be worse, right? It's not like it's plague, right? It falls into that "famous last words" file, an abundance of memes in which the year 2020 says "Hold my beer" and then it surely does get worse.

Because as bad as coronavirus is — and it is bad, make no mistake about it — Black Plague was worse. (So far, anyway.) Also known as Bubonic Plague, also known as the Black Death (this isn't getting any easier, is it), in the mid-1300s it ravaged — devastated — depopulated — Western Europe, sweeping away fully half of the population, according to History Daily. Depending on which part of the body was infected first, mortality rate was anywhere from 60-100 percent. And it's not as though the patient went gentle into that good night, either. Lymph nodes became massively swollen throughout the body, including the groin; fevers spike horrifically. Patients experienced nausea, vomiting, and terrible aches and pains, says History. "After that, the body begins to rapidly rot, and the skin and nails turn black, all while the person is still alive, though not for long," History Daily says. Patients sometimes went to bed healthy, developed symptoms, and were dead by morning. Yersina pestis, for the bacteriologists out there, spread through the air, and through bites from fleas and rats.

Plague is spread by bites from rats and fleas, and through the air

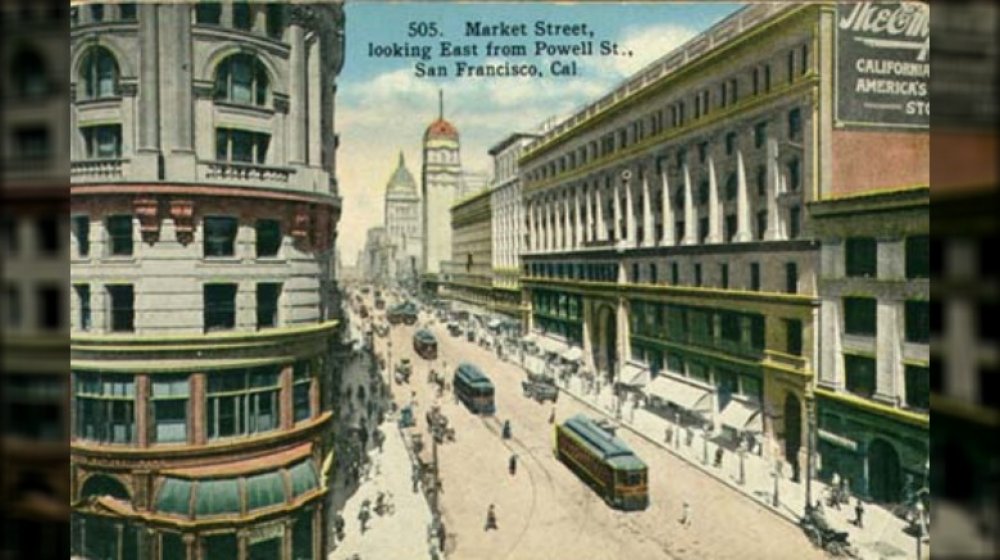

None of which was good news in San Francisco in 1900, when, The Science History Institute tells us, a resident named Wong Chut King died with plague symptoms. City officials responded by quarantining 20,000 residents of the city's Chinatown, and at least one newspaper reassured white readers that the sickness was "largely racial." The dangers were downplayed — after all, what would happen to the port, to tourism, to business, if word got out that San Francisco was a modern-day plague pit? The Board of Health announced its findings, but California's governor "refused to believe it or to do anything to help in the antiplague effort," says PBS's A Science Odyssey. It took a new governor for pro-active public health efforts to take hold. It was too late for the 121 cases in San Francisco, the five outside the city, and the 122 people who died as a result.

By 1904 things had settled down, but only temporarily. The great San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 destroyed enormous sections of the city, making both people and rats homeless. There was a spike in cases, but a rat-catching initiative helped curb the outbreak. The last case was reported in 1909.