The Legend Of Baba Yaga Explained

In the thrice tenth kingdom beyond the thrice nine lands flourishes a vivid world full of talking wolves, shimmering firebirds, immortal soldiers, and a truly improbable number of boys named Ivan and girls named Vasilisa. But looming above all these fantastic elements of Russian fairy tales and folklore is the terrifying Baba Yaga, a voracious swamp witch who wants only to gobble up fat children after forcing them to do chores for her.

Sure, Baba Yaga is Russian, she's scary, and she wants to eat you, but there's so much more. How do you know when you've found a Baba Yaga and not just a generic forest witch? Is she definitely going to eat you, or might she instead play the role of a beneficent yet still vaguely sinister mother figure? Can you go to her for a solid deal on a good horse? For answers to all these and more, read on.

What does 'Baba Yaga' mean?

In the John Wick film series, it is revealed that the titular assassin is known among the Russian mob by the epithet "Baba Yaga," which they translate as "the Bogeyman." One could give the screenwriters the benefit of the doubt and say that they were trying to convey a sense of menace by comparing Wick to Russia's most famous monster, or, as Russia Beyond suggests, maybe they were thinking of the babayka, a monster from Russian folklore more in line with the concept of bogeyman. But there's no way around the fact that there's a hit action franchise where the main character's nickname is "Spooky Grandma."

While the exact origin of the name Baba Yaga is hard to pin down, the baba part is pretty easy: it's a Slavic word that means old woman, grandmother, or witch, related to the more familiar modern Russian word for grandmother, babushka. The "yaga" part (which is pronounced with the accent on the second syllable, by the way) is harder to pin down. It's possible that it's a diminutive of the Slavic name Jadwiga, but there's also a chance it comes from various Slavic words meaning "abuse," snake," or "wicked." So "terrible old witch" or the obviously superior "spooky grandma" are solid translations, likely neither something John Wick wants to be known as.

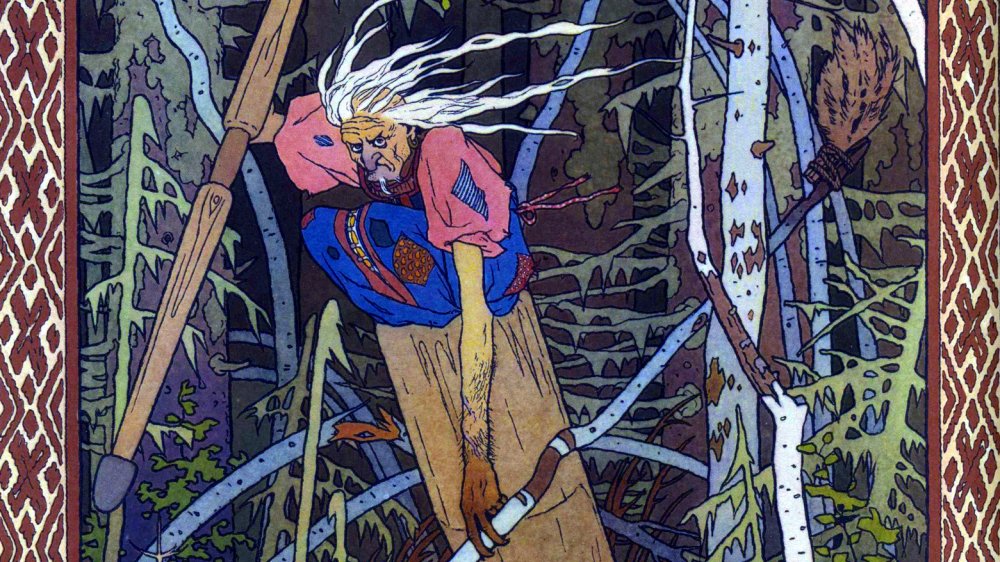

The iconic look of the Baba Yaga

Russian folklore abounds with stories featuring the Baba Yaga, and the old witch can vary wildly from story to story, sometimes a clear sinister villain, sometimes a supernatural mother figure. But whether she's a wicked witch or fairy godmother, her general look is pretty consistent. As Ancient Origins explains, the Baba Yaga is usually described as having an unnaturally long nose, sometimes said to stretch to the ceiling when she sleeps, and iron teeth. She is often said to be like skin and bones, despite her voracious appetite. Her common epithet is "bony-legged." Nevertheless, her prodigious size is one of the more threatening elements of her presence: heroes in stories who enter her house often find her laying atop her enormous cooking stove that stretches from one end of the house to the other.

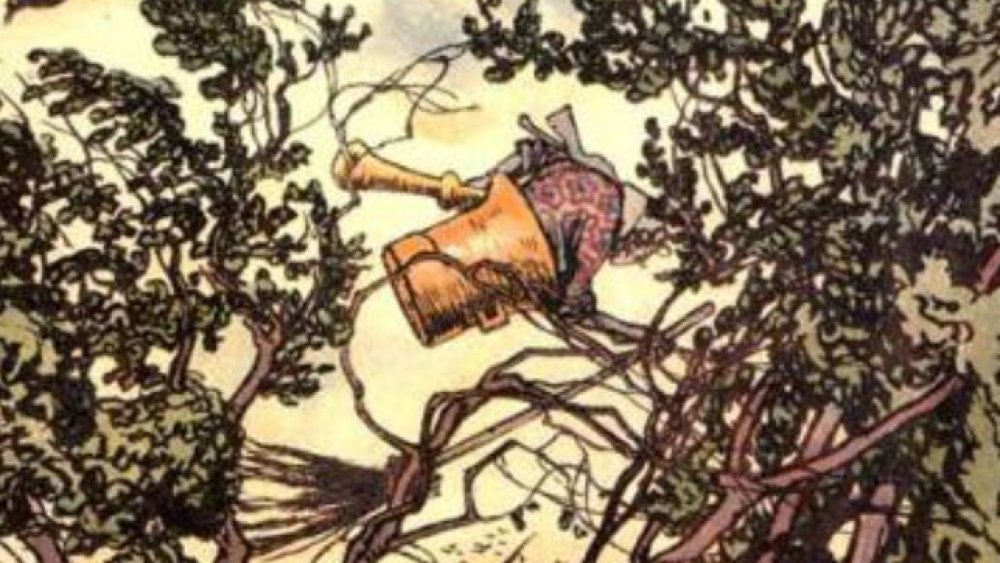

While long noses and bony fingers might be a common look for fairy tale witches, the Baba Yaga really stands out by her most common means of conveyance. The Baba Yaga is known to get around by sitting in a giant flying mortar that she steers with a proportionately large pestle, which serves as a sort of magical rudder. As she flies past, she sweeps away her tracks with a birch broom, leaving no trace behind her, a frustrating habit for whatever the Baba Yaga equivalent of Bigfoot hunters is.

The hard-to-mistake chicken leg house

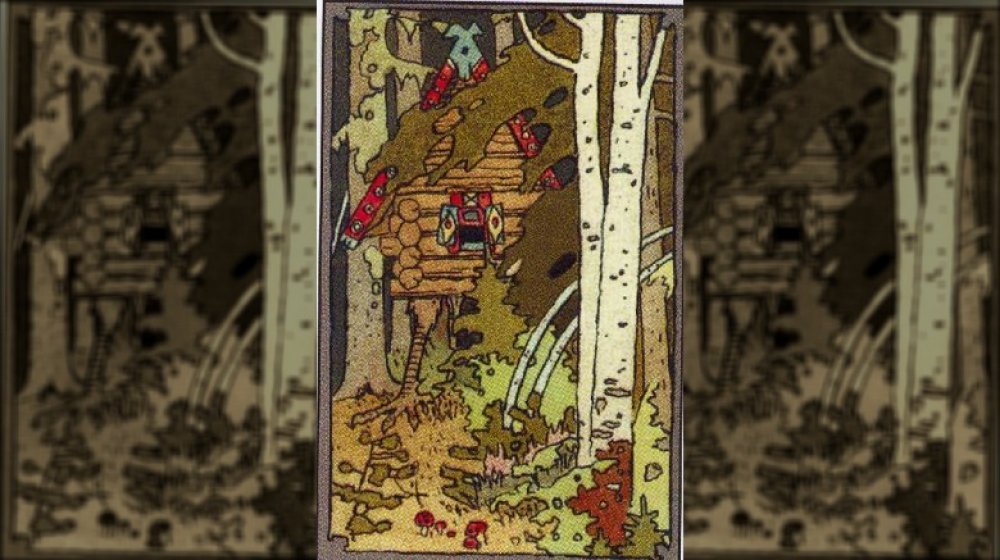

One of the surest signs that you've encountered the Baba Yaga is her house. It's one of those "you definitely know it when you see it" kind of things. You might, for example, be unsure about whether the house you saw was actually made of gingerbread, or if that spooky house on the corner is actually haunted. But there's no mistaking the Baba Yaga's chicken leg hut. "Is that a figure of speech?" you might be asking. No. The Baba Yaga lives in a chicken leg house.

As the Encyclopedia of Fairies in World Folklore and Mythology explains, the Baba Yaga lives in a log cabin-style hut perched atop a pair of giant, moving, dancing chicken legs. The house can move around on these legs, and the Baba Yaga is known to ask the house to turn around when she needs it to. This is something of a security measure, as the house will not turn to reveal its door to someone approaching it until they speak the magical phrase, "Turn your back to the forest, your front to me." The off-putting nature of the house is not limited to the legs, however. The door's keyhole is a mouth full of razor sharp teeth, and the fence around the hut is made of human bones topped with lamps made of the skulls of the witch's victims, with one post always conveniently left empty for the hero's head, should they slip up.

The ambiguous morality of the Baba Yaga

While there's no doubt that the Baba Yaga cuts a sinister figure, chasing innocent children through the Russian forest on her enormous wooden pestle or attempting to gobble them up in her magical witch house, throughout the whole of Russian folklore, the old forest crone is hardly unambiguously evil. As Vice explains, she's nearly equally likely to be a cannibal monster or supernatural mother figure, sometimes even in the same story. As an example, across the course of the famous story "Vasilisa the Beautiful," the Baba Yaga is equal parts trickster, monster, and savior in succession.

This ambiguity is no accident, but rather is tied to her connection to femininity and the natural world, as a sort of earth mother. In one story, a young princess flees the witch's hut to escape ending up in her oven, and during her flight ends up creating a mountain range, a forest, and a lake with various magical items to slow the Baba Yaga down. In this way, the seemingly monstrous Baba Yaga has led to the creation of a new world. This duality reflects Russian culture's overall perception of women, as figures of both maternal love and mercurial, seductive duplicity, and especially a fear of a woman who operates outside the bounds of a male-dominated society. The Baba Yaga is both a mother and a trickster because these are the modes in which many men see all women.

How Vasilisa the Beautiful got fire from the Baba Yaga

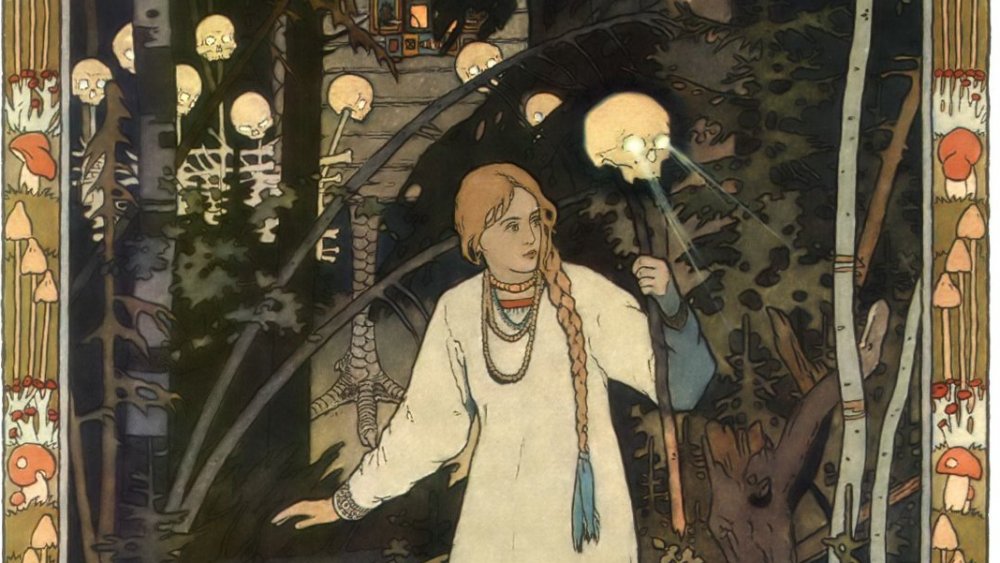

Arguably the most famous fairy tale featuring the Baba Yaga, and maybe even the most famous Russian fairy tale period, is "Vasilisa the Beautiful," which tells of a pretty young girl who–stop us if you've heard this one–lives with her wicked stepmother and two ugly stepsisters. The stepmother runs Vasilisa ragged with increasingly difficult chores, which the girl is always able to accomplish through the agency of a magical doll given to her by her late mother. When Vasilisa becomes old enough to marry, her stepmother decides to get rid of her so her beauty will stop distracting suitors from her own daughters. To this end, she sends Vasilisa on her hardest errand yet: to fetch fire from the Baba Yaga.

The girl makes her way to the chicken leg hut, where the Baba Yaga immediately puts her to work to pay for the fire. The witch sets before the girl a series of impossible tasks, which she is able to finish thanks to her magic doll. Despite being surrounded by eerie sights like disembodied pairs of hands and the Baba Yaga eating inhuman amounts of food, Vasilisa keeps her cool and is polite to her witchy benefactor. In the end, the witch gives Vasilisa fire held within a skull, which, when Vasilisa brings it home, burns the stepmother and stepsisters to ashes. Vasilisa survives and marries the Tsar, of course.

The Baba Yaga's colorful servants

One of the most notable details from the story "Vasilisa the Beautiful" is not the strange and menacing happenings inside the Baba Yaga's hut, like the invisible servants or the constant looming threat of cannibalism, but rather what the title heroine spies through the window happening just outside the chicken leg house. When the Baba Yaga tasks the girl with separating a pile of grains, Vasilisa's magic doll tells her to rest and let the doll take care of it. When Vasilisa wakes in the morning and sees the firelit dim inside the skull-topped fence posts, she spies a rider dressed all in white galloping upon a milk-white horse around the house. The rider then jumps a wall and vanishes. Soon she spies a rider in red on a blood-red horse who does the same. In the evening, when the Baba Yaga returns to check on Vasilisa's work, the girl sees a rider in black on a coal-black horse galloping around the hut before vanishing like the others.

After Vasilisa has done all of the witch's tasks to her liking, the girl works up the courage to ask the Baba Yaga who these riders were. The Baba Yaga reveals that the white, red, and black riders were the day, the sun, and the night, respectively, all of whom she refers to as her faithful servants. Wisely, Vasilisa asks no more questions of the witch.

The normal behavior of counting strangers' spoons

Some stories attribute unusual behavior to the Baba Yaga that is not ever mentioned again in other stories, but which nevertheless stick in your head just from pure strangeness. One such story is "Baba Yaga and the Brave Youth," in which a, well, brave youth lives together with, obviously, a cat and a sparrow. The cat and sparrow repeatedly go into the woods to cut wood despite being the two without thumbs, leaving the brave youth behind with one warning: if the Baba Yaga comes to count the spoons, hide and don't say anything. Three times the Baba Yaga comes to the house to count the spoons, and three times the boy can't hold his tongue when he sees the witch touching his spoon. The first two times the cat and sparrow chase the witch off, but the third time she snatches him off to her hut to eat him.

Another unusual detail in this story is that here the Baba Yaga has three daughters. The Baba Yaga tells each daughter in turn to cook the boy, but he tricks each one of them into cooking themselves instead by acting like he doesn't know how to lie in a pan and asking them to show him. Pulling the same trick a fourth time leads to a cooked Baba Yaga and a youth running bravely home.

Baba Yaga's discount horse emporium

Baba Yaga isn't the only recurring villain in Russian fairy tales. One of the other most commonly seen threats in these stories is Koshchei the Deathless, a terrifying soldier who cannot die, usually because his soul is hidden away nesting doll-style inside a series of increasingly large animals (for example, it might be in an egg inside a duck inside a rabbit inside a goat or whatever). One story that includes both Koshchei and the Baba Yaga is the classic "Maria Moryevna," in which a prince named Ivan falls in love with the titular warrior princess and then accidentally frees the immortal killer she has chained up in her basement.

Koshchei subsequently kidnaps Maria Moryevna, and Ivan sets out to pursue them. It ... doesn't go great. The first time Ivan catches Koshchei, the villain kills him and throws his dead body out to sea in a barrel. Fortunately, Ivan's brothers-in-law are powerful wizards who are able to restore him to life. They tell him that the only way to defeat Koshchei is with a horse from the Baba Yaga. Baba Yaga, you see, breeds mares so fast that they can circle the world in a day. Ivan manages to pass the Baba Yaga's series of tests and earns himself a magic horse with which he catches up to Koshchei, burns him to ashes, and returns home with his wife.

Magic birds and a talking river of milk

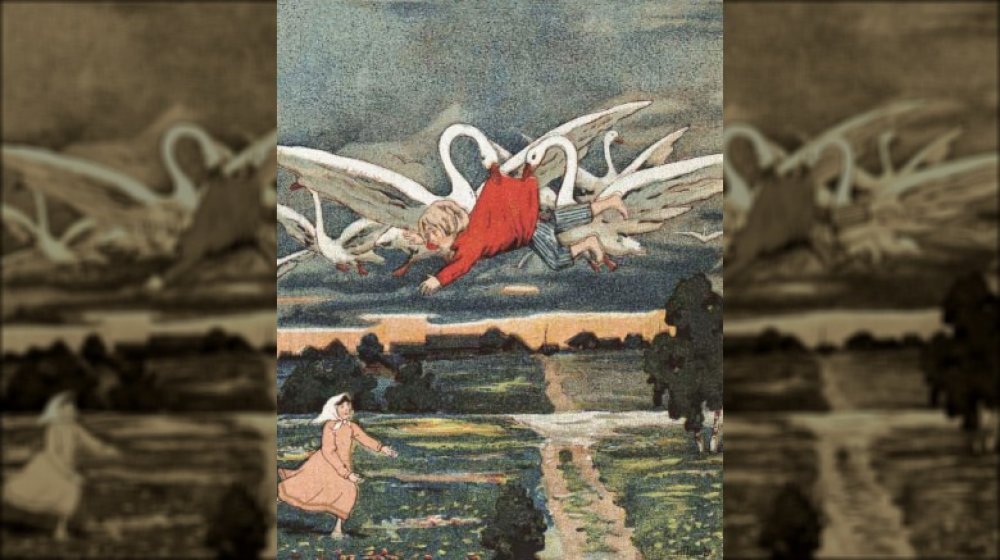

What is a swan goose? Well, despite sounding like the sort of fictional animal mashups Aang and the gang encounter on Avatar: The Last Airbender, it turns out it's an actual kind of goose that lives in Russia, China, and Mongolia. It is also apparently a foul magical weapon (pun intended) in the bony hands of the Baba Yaga. While not a common occurrence in the various tales of the Baba Yaga, magical swan geese are the main plot device at the center of the story called, appropriately enough, "The Magical Swan Geese."

In this particular tale, a careless young girl loses track of her younger brother, and from a talking oven, tree, and milk river, she finds out he was carried away by magical swan geese. In her search, she finds her brother inside the Baba Yaga's hut. The witch sets her to the task of spinning flax, and a mouse pops up to warn the girl that the Baba Yaga plans to steam the two children to death in her bath house, eat them, and ride away on their bones. The mouse helps the children escape, and they run home pursued by the swan geese. It's only with the help of the talking oven, tree, and milk river that the two kids are able to escape the witch geese's clutches and return home. Fairy tales are pretty weird.

Why settle for one Baba Yaga?

One explanation for why the Baba Yaga might seem different from story to story–benevolent or cruel, a horse dealer or a goose tamer–or how she keeps popping up even if she dies at the end of some stories, is that there's not just one Baba Yaga. If the name just means "spooky grandma," that's not necessarily a proper name, but maybe just a descriptor for a particular type of swamp witch, all of whom apparently found a clearance sale on houses with legs and novelty size mortars and pestles. That there are multiple Babas Yaga is made more explicit in stories in which there are literally multiple Babas Yaga, such as "The Maiden Tsar."

In this story, a merchant's son (named Ivan, of course) falls in love with the titular maiden tsar, only for the two to be separated through the treachery of the boy's tutor and stepmother. Ivan goes to seek his beloved in the thrice tenth kingdom beyond the thrice nine lands, stopping to inquire at a certain chicken-legged hut. The Baba Yaga inside tells him she does not know where to find the thrice tenth kingdom, but to ask her sister. Ivan then asks a second and then a third Baba Yaga, who tries to eat him until he escapes on a firebird's back. Ivan then has to find the maiden tsar's love hidden in an egg, but don't worry: there's a happy ending.

How the Baba Yaga stole Christmas

Within the world of Russian folklore, the (usually) malevolent presence of the Baba Yaga is balanced somewhat by the (usually) benevolent figure of Morozko, a powerful winter wizard whose name is generally translated as "Jack Frost" or "Frosty" or "Father Frost." The two supernatural forces actually butt heads in the classic 1965 Soviet fantasy film Morozko (known as Jack Frost in a 1997 episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000), which is an adaptation and expansion of the fairy tale of the same name.The grandfatherly Morozko rescues the innocent Nastya and the well-meaning dunderhead Ivan from the clutches of the wicked Baba Yaga and her murderous black cat, who tricks Nastya into freezing herself by touching Morozko's magic staff. This movie is possibly the best way to see the Baba Yaga and her chicken leg house in action in a delightful if silly fantasy romp.

Morozko's benevolence only grew as he came to be associated with Ded Moroz ("Grandfather Frost"), the Russian equivalent of Santa Claus, who bring presents to good Russian and Russian-adjacent children on New Year's (rather than Christmas, thanks to traditions started during the secular Soviet era). In modern celebrations, Frosty Grandpa can be seen butting heads with Spooky Grandma at the holidays, when the good wizard and his beautiful granddaughter fight off the Baba Yaga's attempts to steal the presents from under the New Year's tree.

The Baba Yaga as modern icon

The numerous appearances of the Baba Yaga in so many fascinating classic stories has led to her occasional reappearance in modern culture. One place where she has made a significant mark is in the Hellboy universe of comics, where Hellboy himself encounters the Russian witch in 1964 as she's counting the fingers of the dead and shoots one of her eyes out in an attempt to kill her. The Baba Yaga swears revenge and pulls out all the stops against him, summoning Koshchei the Deathless and his armies to take Hellboy's eye in retaliation. Her prominence in the comics led to her having a role in the 2019 Hellboy movie, including Hellboy going to the chicken leg house and shooting the Baba Yaga's eye out.

Outside of comics and films, the Baba Yaga has become something of a semi-ironic feminist icon. As Vice explains, the idea of a powerful old woman who lives alone in the woods and does whatever she wants is somewhat aspirational for today's young woman. The Hairpin's humorous advice column (and subsequent eponymous book) "Ask Baba Yaga" applies the swamp witch's perspective to such questions as "How can I stop craving male attention?" and "Am I watching too much television?" (The answer to which is, helpfully, "The egg can be rolled down the hill & hidden in a burrow [sic]; the egg can be dropped into a river.")