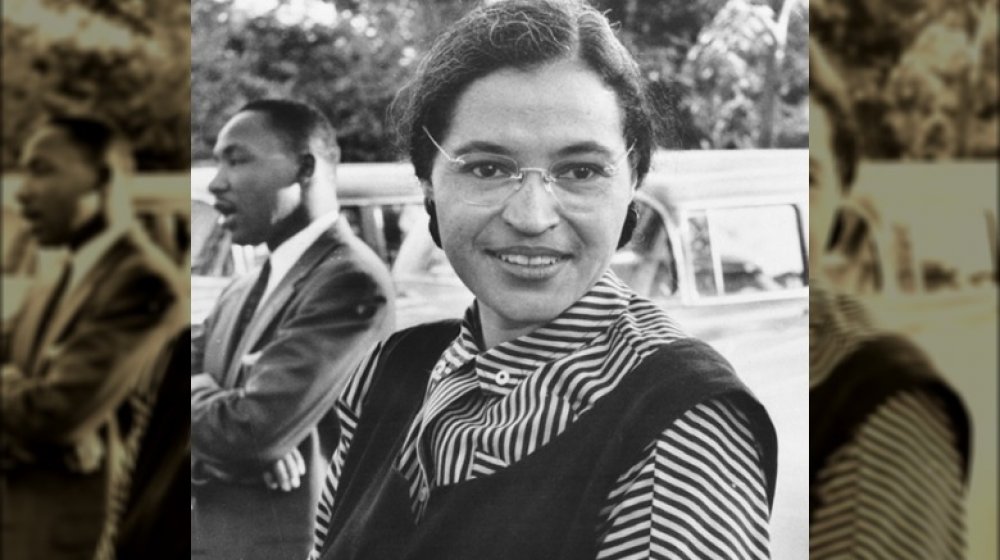

The Untold Truth Of Rosa Parks

When it comes to civil rights activists who made a lasting impact on history, Rosa Parks is one of the first names that comes to mind. We think of her as just refusing to give up her seat on a bus, and that's true. But that's also a simplified version of her story and all that she did.

She was born in Tuskegee, Alabama on February 4, 1913. Her education was cut short when her grandmother became so ill that she was forced to drop out of school, and according to the National Women's History Museum, her experiences with violence and discrimination were a part of her life from the beginning.

And here's the thing: it's possible you've heard part of the story that says she refused to move because she was tired, and just didn't want to get up. That's a terrible misrepresentation of what happened. Her refusal was a statement: "I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. [...] No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in." So, she did what many wouldn't: she did something about it and helped change the narrative of the world.

Rosa Parks had an incredibly difficult childhood

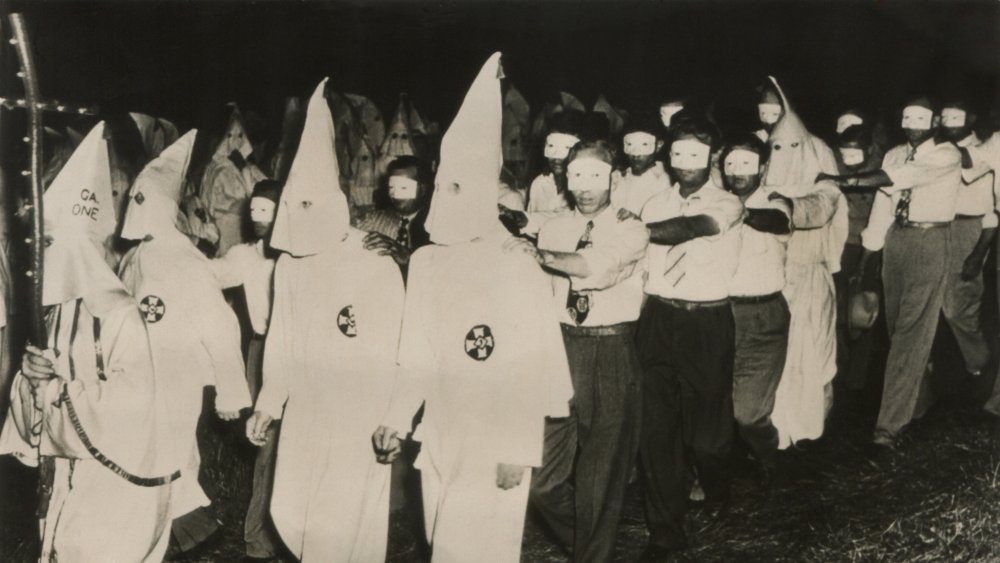

Our earliest memories lay the foundation for our childhood and for the rest of our lives — for Rosa Parks, her earliest memories involved sitting up at night with her grandfather, shotgun at the ready, listening for the seemingly inevitable approach of the Ku Klux Klan. According to The Washington Post, Parks' grandfather, Sylvester Edwards, was the son of a white plantation owner, and he knew all too well what came with the KKK when they came knocking. The family home was boarded up to afford them extra protection, and she grew up wanting a confrontation. She later wrote, "I wanted to see him kill a Klu-Kluxer. He declared that the first to invade our home would surely die."

Her childhood was punctuated with violence and threats... and Parks grew up knowing exactly why she was so bullied. When she was 10, she was pushed around by a white boy, and she fought back: "I picked up a brick and dared him to hit me. He thought better of it and went away," she wrote later.

Rosa Parks was still young when she decided she was going to devote her entire life to fighting for equality and justice. When she was 19, she married Raymond Parks — he wasn't just the love of her life, but he shared her passion for social justice.

Here's why her refusal to give up her bus seat was such a big deal

Rosa Parks' act of defiance is usually seen as a spontaneous act of rebellion, but it wasn't. Local civil rights leaders had long been planning to challenge a city ordinance requiring black passengers sit in the back of the bus, and if the white, front section of the bus was full, they had to give up their seats entirely. And that's what happened with Parks. She was sitting in the first row of the "colored section" of the bus, when she and her companions were told to leave their seats for white passengers. She refused to move, was arrested, and it kicked off the bus boycott.

According to History, it wasn't Parks' first experience with that particular driver, either. Black passengers had to board in the front to pay, then get off the bus and back on through a back door. When Parks got off to re-board, he pulled away and left her behind.

On August 12, 1950, a Montgomery man named Hilliard Brooks got on one of the city's buses. He paid his fare... and started walking to the back of the bus, past a white teenager. When the bus driver yelled at him to get off the bus and back on through the back, he said he wasn't hurting anyone, and he was almost to the back anyway. The driver flagged down a nearby police officer and together, they dragged him through the bus, beating him with clubs and kicking him out the door into the street. Then? The officer shot and killed him. Rosa Parks would later write of her sorrow (via Northeastern), that his murder "passed unnoticed except by his family..." The officer was never prosecuted.

Rosa Parks was following in the footsteps of a 15-year-old girl

When it comes to challenging Montgomery's discriminatory bus laws, Rosa Parks wasn't the first. On March 2, 1955, a 15-year-old girl named Claudette Colvin did the same thing. When she and three schoolmates were told to give up their seats for a white passenger, she refused. Two police officers quickly got involved, and Colvin told Time, "I feared they might hit me with their clubs. They were trying to guess my bra size, and teasing me about my breasts. I could have been raped."

Instead, they knocked her books on the floor, dragged her off the bus, and put her in their squad car. She spent the next few hours in jail, until her mother and her pastor came to get her out. She told the BBC that her entire family feared they would be targeted because of her actions: her father sat up that night, with other members of the community, watching and waiting for the KKK.

Rosa Parks was well aware of Claudette Colvin's actions, and spearheaded fundraising efforts for her case. When the case went to court, she was found guilty only of assault — meaning, notes CUNY — that the case no longer had anything to do with segregation. Afterwards, Parks got Colvin active in the local Youth Council, even though Montgomery's civil rights leaders decided not to put the burden of their work on a teen.

Rosa Parks had been active in the NAACP for years before the bus protest

By the time Rosa Parks took a stand on that Montgomery bus in December of 1955, she already had years of work as a civil rights activist under her belt. Raymond Parks was a longtime member of the Montgomery NAACP, joining in 1934. According to CUNY, he had originally thought it was too dangerous for his wife — but, after she saw a picture of a female classmate who was a member, she decided she was going to go, too. Her first meeting was in 1943, and at that meeting, she was elected as the chapter's secretary. Over the next 10 years, she and E.D. Nixon would concentrate on telling the stories of those who had been silenced.

And it was a terrifying time: Nixon would recall, "Mrs. Parks will tell you this. Her mother said the white folks was going to lynch us, her and me both. Mrs. Parks and I were in the NAACP when other Negroes were afraid to be seen with us."

Even as she restarted the youth branch of the organization and encouraged peaceful protest, a major part of her job was to record incidents of violence and discrimination, in the hopes that at some point, they would be able to see justice for victims.

Rosa Parks spent years as a sexual assault investigator

A large part of Rosa Parks' work was as an investigator in sexual assault cases, something that she became involved in after her own experience: in 1931, she was the victim of an attempted assault by a white neighbor. She would later write (via History), "I was ready to die but give my consent never. Never, never."

Parks took victim statements from countless women, and in 1944, a 24-year-old woman named Recy Taylor was abducted and raped by six attackers. Just a few days later, the Montgomery NAACP heard of the attack, and sent Parks to investigate. The men had threatened to kill Taylor if she told, but friends had already reported seeing her forced into a car, and according to The Washington Post, they absolutely and definitely reported exactly what happened. One of the assailants confessed and named the others... but none were arrested.

Rosa Parks was there to find out why, and after the sheriff informed her that they didn't want any trouble, she formed the Alabama Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor. The case made national news, and in spite of national coverage, the men were investigated several times... but never prosecuted. It wasn't until 2011 that the state of Alabama issued an apology for their misconduct.

Rosa Parks was involved in the landmark 'Scottsboro Boys' case

Rosa and Raymond Parks met in 1931, and married in 1932 — right in the middle of a massive court case. First, some history: in 1931, police arrested nine black teens, all between 13- and 19-years-old. They had been on a Southern Railroad freight train when a fight broke out, and two white, female passengers accused them of rape. Outrage spread fast, and the Alabama National Guard stepped in to try to keep the peace. Eight were found guilty and sentenced to death, while the fate of 13-year-old Leroy Wright would be put in the balance: a single juror favored life in prison instead of the death penalty.

Meanwhile, the newlywed Parks were working tirelessly to try to save the boys' lives — and it was incredibly dangerous work. Everyone working within their group to that end goal was simply known as "Larry," meeting times and places varied, and communications were sent via secret signals. Raymond Parks visited the boys in jail, brought them, food, and gave them hope — while two of their associates were murdered, police intimidation increased, and every time Raymond would come home, Rosa would think (via CUNY), "At least they didn't get him that time."

One of the boys' accusers recanted her testimony, and instead, testified for the defense. They were still convicted. In 2013, The New York Times reported that three were given posthumous pardons.

Cleaning up a KKK-bombed house

The threat of violence from groups like the KKK was a constant in Rosa Parks' life, and in 1957, one of her neighbors had their home bombed by the radical organization.

The Rev. Robert and Jeannie Graetz were — alongside the Parks — leaders in the area's civil rights movement. Shockingly, it was the second time their house had been bombed: the first was in 1956, not long after Parks' protest. The Graetzes, says The Birmingham Times, believed they were high on the KKK's hit list because "We raised the ire of the local Klan as soon as we moved to Montgomery, because we are a white couple, and my husband was the minister of an all-black Lutheran congregation," Jeannie later said. "We also chose to live among our flock, and then we publicly supported the desegregation of Montgomery's buses beginning in 1955. Because of those reasons, we were marked targets."

Rosa Parks documented the bombing incident in a letter, which the Graetzes bought at auction years later, and gave to Alabama State University. The details are tragic... and fortunate, in that no one was harmed. The entire Graetz family was home at the time of the explosion, which ripped off the roof, shattered every window, and tore all the doors off their hinges. After the explosion, Rosa and Raymond Parks were on scene, helping them clean up. Arrests were made, but the men were found not guilty.

Rosa Parks became an outcast after her arrest

While it might seem that Rosa Parks' protest and her arrest would solidify something of a following around her, quite the opposite happened. According to Time, she would write of the months following her arrest that she felt "lonely and crazy," watching her family start to struggle as a consequence of her actions.

In the year after her arrest, History says that her outspoken activism led to very rapidly deteriorating relationships with her coworkers, which turned into fights and finally, Parks lost her job at the Montgomery Fair department store. According to her niece, Urana McCauley, "She was disheartened that her black coworkers did not want to speak to her. If you were doing anything for change, you were an outcast. [...] People just stopped speaking to her until she was let go."

Rosa Parks' husband, too, quit his job as a Maxwell Air Force Base barber after being told that he couldn't mention his wife... at all (via Biography). And after that, no one wanted to hire either of them — she was too high-profile even for the Montgomery Improvement Association, the organization that had coordinated the bus boycott. Parks had volunteered for them for years, but still, they wouldn't hire her. With no way to make ends meet, the Parks had no choice but to leave Montgomery in hopes of finding a fresh start.

The death threats, and peace in faith

After Rosa Parks' protest, there was a certain part of the population that wanted nothing more than to discredit her. According to Time, rumors started circulating, and they included everything from an accusation that she wasn't even black, to accusations that she had a car, and didn't even need the bus.

Then, there were the threats. She wrote (via Beacon Broadside), "There were people who called to say that I should be beaten or be killed, because I was causing so much trouble. [...] I remember one person calling and saying she was sorry, and then laughing at the end of the conversation before hanging up." Most of the time, Parks says, She knew when the conversation was going to become abusive, and she'd simply hang up. But when her mother answered the phone to that kind of abuse... that bothered her more than being on the receiving end herself.

Rosa turned to her faith, but Raymond struggled daily. Her friend Mary Hays Carter described her mindset like this: "Well, you have to die sometime. I never set out to plan to hurt anyone...." but as her husband sank deeper into depression and the threats kept coming, it certainly didn't get easier.

Rosa Parks in Detroit

After first attempting to find work in Virginia, Rosa Parks ended up moving to Detroit. She picked up the odd sewing job here and there, and this is where, Biography says, she had a tumor in her throat removed, and was treated for an ulcer that had developed around the stress of the bus boycott. By 1960, Jet magazine wrote that she was a "tattered rag of her former self — penniless, debt-ridden, ailing with stomach ulcers, and a throat tumor, compressed into two rooms with her husband and mother."

Finally, things started to turn around — by 1961, she was on the mend. Her husband had a steady job, and she was finally healthy enough to have a steady sewing job, as well. At the same time, she remained a voice in the civil rights movement, and in 1964, she volunteered for the congressional campaign of John Conyers, who was so impressed with her that when he won his seat, he hired her as his assistant.

Conyers and Parks remained close, even after her retirement in 1988. According to The Nation, Conyers described her like this: "Mrs. Parks was there with me at the beginning of my career... I am therefore one of the lucky few who have had the privilege of being able to call her my colleague, as well as my friend."

Robbery, assault, and a strange benefactor

In 1994, The New York Times ran an article showing how little had changed. Rosa Parks — now 81-years-old — had been robbed and assaulted in her home. According to the report, a single person kicked open the back door of her Detroit home. When she went downstairs, he hit her and fled, stealing around $50. Officers took her to the hospital, where she was treated for facial injuries and released.

The incident came to the attention of a federal judge named Damon Keith, who also happened to be a Detroit native. He took it upon himself to find Parks a safer place to live, and that was at the city's Riverfront Apartments. That story made papers, too, and one of the people who read the piece reached out to Keith and volunteered to pay Parks' housing costs indefinitely.

That man? That was Mike Ilitch, says CNN, the founder of Little Caesars. Starting in 1994, Ilitch continued to quietly pay her rent until her death. In 2004, Rosa Parks was diagnosed with progressive dementia, and she passed away in her Detroit apartment on October 24, 2005 (via Biography).

Her Detroit home has become strangely controversial

Rosa Parks lived an incredible life, and recently, the house she and her husband first moved into in Detroit has taken on something of a life of its own. The tiny house was once the home of not just the couple, but 17 other relatives as well. It was ultimately abandoned, and according to The Guardian, it was slated for demolition in 2008. That's when Parks' niece, Rhea McCauley, bought it for just $500 and donated it to an artist named Ryan Mendoza.

Mendoza spent a hefty amount of time trying to convince Detroit officials to preserve the house, and in 2016, he finally gave up... sort of. He ultimately dismantled the house, had it shipped to his studio in Berlin, Germany, and reassembled it. It was just a temporary solution, and McCauley and Mendoza continued to work together to try to find a permanent home for it. He thought he had — after talking to Brown University, he dismantled it, shipped it across the Atlantic again, and started to set it up at the WaterFire Arts Center in Providence.

But Brown suddenly cancelled, saying in an email to AP, "The 'house' is simply not a human interest story." While it seemed like things were going to go completely sideways, The Detroit Free Press announced in late 2019 that the house was going to stay in Providence at least for a while.