The Crazy True Story Of The North American Fur Trade

No Western film library is complete without a copy of 1972s Jeremiah Johnson, the fictional story of an ex-soldier who forsakes living in a civilized world to forage in the woods as a mountain man and trapper. It doesn't hurt that the movie starred Robert Redford as the dashing young Johnson, who precariously balances his relationships with Native Americans and the army while trying to achieve his dream—with nary a beautiful blond hair out of place. What the movie doesn't make clear is that the fur trade was an important time in history and contributed to the growth of the United States.

Although the movie is set in the 1850s, the fur trade dates further back in North America. Money had no place here; rather, trappers learned to trade goods with Natives and others to make their way in the world. According to the National Cowboy Museum, the fur trade was largely responsible for opening up the West to white settlers. And History Colorado confirms that fur trapping was hard, grueling work. Over time, much of the fur trade history has been romanticized to a degree, with myth often replacing facts. Read on to see how the fur trade helped actually settle the West.

The fur trade during the 1500s

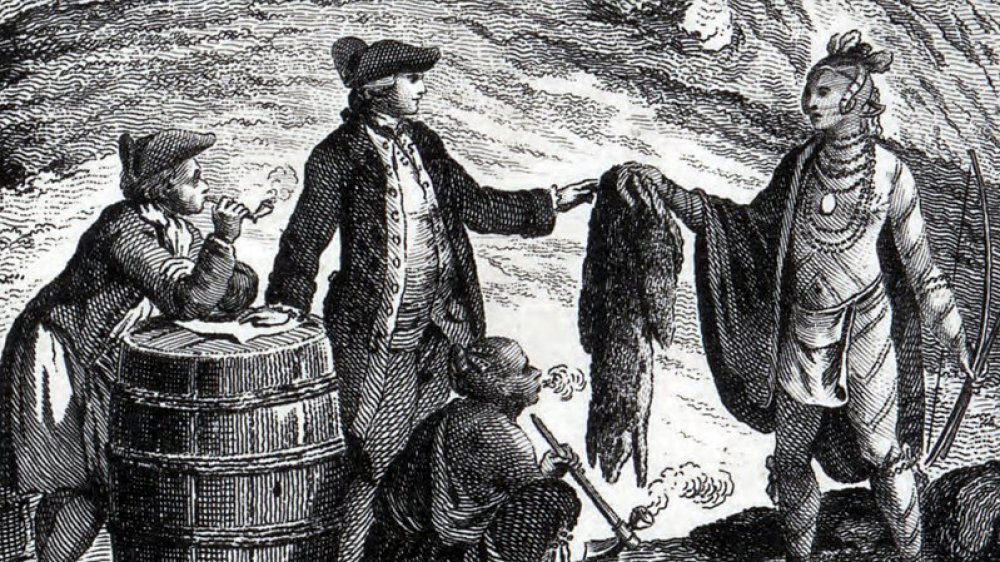

According to White Oak (via Wayback Machine), Europeans first arrived to explore North America in the 1500s. They were the first to introduce manufactured goods to the Native Americans, trading such important items as cookware, hatchets, knives, guns, woven cloth, and more. In return, the Natives traded a variety of fur pelts and meat, as well as information about the unknown territory. All were integral to survival at the time. Much of this early trading took place along the St. Lawrence River in Canada, and eventually worked its way south towards New York and, eventually, further west.

By establishing trade, French and European trappers made friends with the indigenous peoples around them. Canada History Project says the First Nations offered up a variety of pelts, ranging from fox and marten to mink and otter. In time, beaver pelts became especially desirable. European traders brought these prized furs back to Europe, where they were used to make coats and highly fashionable beaver-felt hats, according to Montana Trappers. Such luxuries had been an item for some time; author Eric Jay Dolan, who concedes that the history of beaver hats "is murky at best," points out that the earliest reference to beaver hats actually appeared in Geoffrey Chaucer's late-fourteenth century Canterbury Tales.

Competition and clashes over fur

According to Montana Trappers, beginning in the 1600s, English settlers made friends with the Iroquois and were eventually able to expand the fur trade the length of the Atlantic coast between Maine and Georgia. European companies began shipping furs from North America. But beginning in 1640, the Iroquois were tired of competition with other Native groups. The tribe instigated what is known as the Beaver Wars in Ohio, fighting others in order to gain control of more land in which to hunt.

The Iroquois people did much more than gain fur-hunting territory during the Beaver Wars. Milwaukee Public Museum verifies that the tribe also "destroyed some tribes such as the Erie, and scattered others such as the Huron." In the end, the Fox, Ojibwa, Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Sauk tribes were chased out of Michigan and wound up in Wisconsin. The Iroquois also managed to disrupt, at least for a time, the transport of furs to the French colony of Quebec in Canada.

The Beaver Wars were waged as late as 1701, when the Iroquois, along with the Huron and Algonquian tribes, signed a peace treaty with New France—an area settled in the St. Lawrence River area which eventually expanded into the Great Lakes region and some of the Appalachian West (per Britannica). The agreement meant the Iroquois would stop chasing other tribes off and would allow "displaced peoples" to return to the land.

The beaver hat craze

It's hard to believe that the formation of America and the West was based on the love of beaver. But beaver pelts have much merit: they are warm, have a "luxurious texture," according to Kelly Feinstein at UC Santa Cruz's history department, and can last a long time. They were so popular in Europe that the fur trade might have been much less important had the European Beaver not been nearly driven to extinction by the 17th century. But alas, Europeans wanted fine, quality hats that would hold their shape and endure rough wear.

White Oak Historical Society explains that "coat beaver" consisted of beaver pelt coats, which Natives actually wore to break them in before trading them. "Parchment beaver" were pelts that were traded fresh out of the trap. More concisely, according to the University of Minnesota, the underbelly portion of the pelt was especially soft and therefore more desirable. Also, beavers secrete a pungent substance called castoreum, which they deposit in small mounds near their lodges, when they mate. Trappers used this secretion to draw beavers to their traps, but also bottled the stuff for transport to Europe, where it was made in a "musk base for flower-scented perfumes." "The Indians say that it is the animal most liked by the French, the English and the Basques, in sum, by all Europeans," wrote Jesuit Paul Le Jeune, noting that one Native told him of receiving 20 knives in return for just one pelt.

The expansion of the fur trade

By the late 1700s, natives of the American plains were not just trading furs, but also buffalo hides and horses to traders from Hudson's Bay. At the time, according to the Fur Trapper, Natives were still a major source for pelts. Notably, a buckskin brought around a dollar, which is why we still call a dollar a "buck" today. The University of Northern Colorado explains that by the early 1800s, it was apparent to Anglo traders that Natives did not necessarily have the manpower, or perhaps the wherewithal, to meet the demands for fur in either Europe or America. This is where the fur companies really took off.

Beginning in the early 1800s, a number of American fur trading companies began. They employed hunters and trappers—mountain men, if you will—to live year-round in the mountains throughout the country and spend their time trapping and shooting for pelts and furs. It was not work for the squeamish, or the weak. As they grew, some of the fur companies, according to Legends of America, began merging together to form even larger companies with branches that included the North West Company, the Pacific Fur Company, and the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. The largest of these would be the American Fur Company, headed by John Jacob Astor (pictured) beginning in 1808.

The fur trade of the 1800s

The National Cowboy Museum explains that before Astor, the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804 was largely responsible for opening both trade and trails to the West. Next, the Treaty of Ghent ended British fur trade in America in 1814, after which Congress forbade anyone who was not a U.S. citizen to participate in the industry, according to Milwaukee Public Museum. American fur trading companies wanted the industry all to themselves, and they pretty much got it.

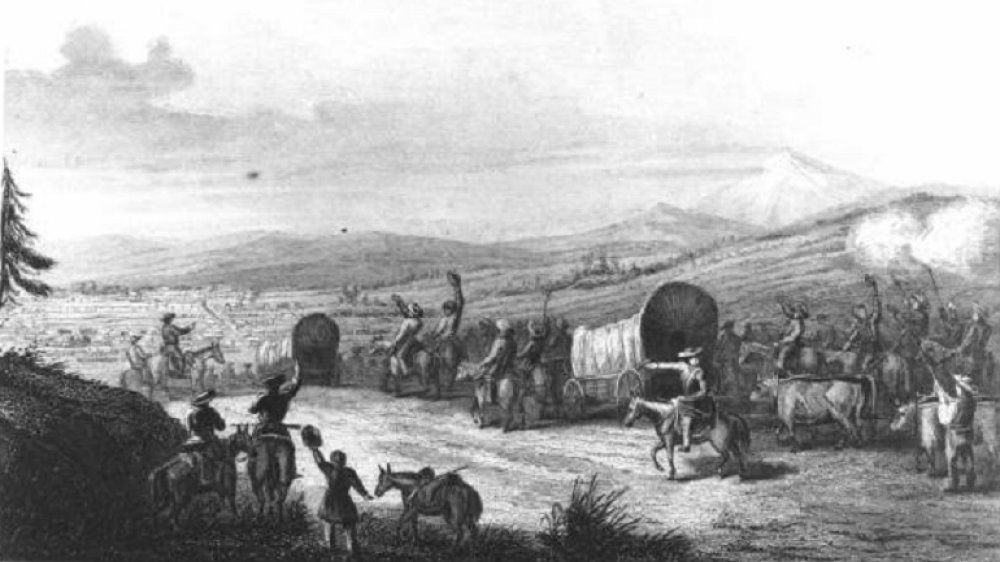

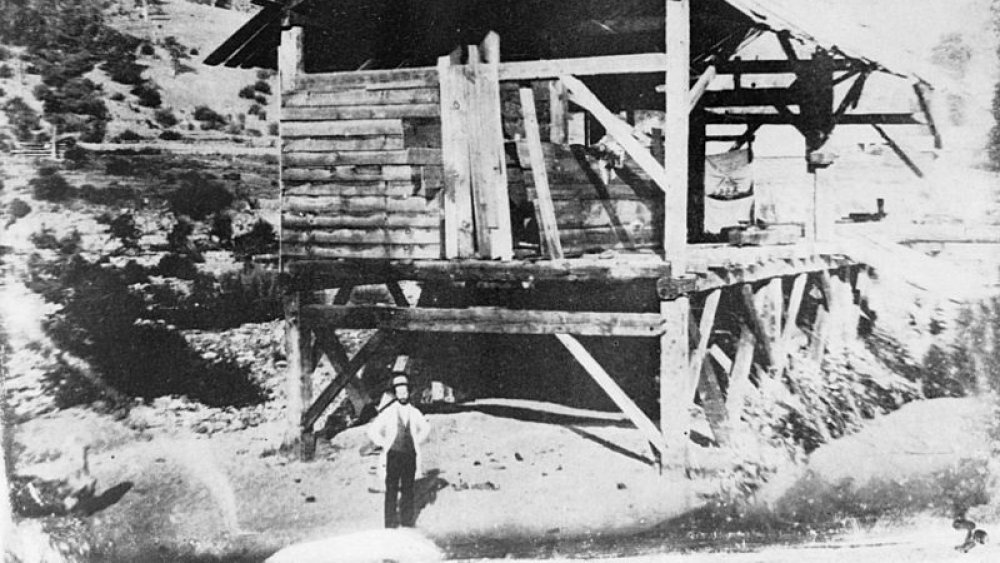

Legends of America cites the top fur companies during the late 1700s and early 1800s. These included two owned by John Jacob Astor, the American Fur Company and the Pacific Fur Company. The others were the North West Fur Company, the Missouri Fur Company, the Columbia Fur Company, and the Rocky Mountain Fur Company. Most unique was Bent, St. Vrain & Company which began in 1833 in Colorado. Founded by Charles Bent and Ceran St. Vrain, the company flourished along the South Platte River in Colorado at Bent's Fort (pictured), established by Charles' brother William. It was one of the western-most operations, located along the mountain branch of the Santa Fe Trail. Those traders, trappers and Natives (primarily Cheyenne and Arapaho) who could not make the annual rendezvous could gather here, peacefully, to trade and gather information.

John Jacob Astor and other important fur traders

John Jacob Astor is credited as the founder of the American fur trade industry in the lower forty-eight states. The man was a real go-getter, once selling nearly half a million muskrat pelts at a New York fur auction, says the Fur Trapper. Although he never came West, according to the Oregon Encyclopedia, he did send men from his Pacific Fur Company to the mouth of the Columbia River between Oregon and Washington to establish Fort Astoria. Astor was not the only one to make history in the fur trade, however. History cites the real men who actually hunted and trapped in the mountains: James Beckwourth, Jim Bridger, Kit Carson, John Colter, Jedediah Smith, and Joseph Walker as equally important mountain men who explored various parts of the country from east to west.

Lesser known but notable mountain men in history include Hugh Glass, who survived a bear attack and was abandoned by his company before straggling for miles to safety. The Revenant, a movie starring Leonardo DiCaprio, was made about Glass's adventures in 2015. Even more obscure is "Rocky Mountain Jim" Nugent, whose gorgeous face was forever scarred by a bear attack. He survived to become one of the most colorful characters in Estes Park, Colorado. Nugent was a learned man who could recite poetry, but was such an awful drunk that he was shot by Griffith Evans and subsequently died in 1874.

The annual rendezvous for trade

Where did trappers take their furs? Between 1825 and 1840, trappers, mountain men, and Native Americans gathered at places across the West every summer. As Rocky Mountain National Rendezvous explains it, these festivals weren't just for doing business. They also were "the trapper's Christmas, New Year's Eve and birthday party; a general-purpose annual blowout and trade fair." Here, men could gather to eat, drink, gamble, socialize, meet others, and trade goods. Wyoming lays claim to the earliest of these, in 1825, on Henry's Fork of the Green River. Subsequent Wyoming meeting spots were at Horse Creek west of Daniel in 1833, 1835-1837, 1839 and 1840; west of Granger in 1834, and near Riverton in 1838.

Other rendezvous took place in Utah (1826, 1827 and 1828), and Idaho (1832). There were 16 in all, each held west of the Continental Divide, says the Fur Trapper. The one exception was in 1831 when Thomas Fitzpatrick, who was bringing many of the supplies from St. Louis, got a late start and missed the deadline for the rendezvous plans to be finalized by a whole two months. There was no FedEx or UPS back then; by the time Fitzpatrick reached Santa Fe to meet up with the others in charge, it was too late. Instead, Henry Fraeb took needed supplies to the trappers who had planned to be at the event, while Fitzpatrick once again headed east to assure having enough supplies for the 1832 gathering on time.

Women and the annual rendezvous

There was another reason mountain men gathered once a year in on spot: to meet, consort with, and even marry Native American women. In the early days of the fur trade, Anglo women were noticeably absent. Dibaajimowin theorizes that "so long as white women were absent on the frontiers, Indigenous women could be used to satisfy the carnal needs of the white men seeking to colonize the continent." Today, the actions of these Native women would be classified as prostitution, but among the tribes, women were not considered a part of any commercial sex trade. Rather, Natives were well accustomed to lending or trading their wives and daughters for sex, always in trade for goods, and the women were often highly respected because of it.

Native women were equally important to their tribe, because it was they who "usually set up camp, dressed furs, made leather, cooked meals, gathered firewood, made moccasins, netted snowshoes, and many other things," according to Northwest Journal. Plus, those who married fur traders and mountain men created better relationships between their husband and the tribe. Trade deals were easier to make, as each benefited from learning about the other's language, culture, and way of life. Not until 1836 says the Fur Trapper, were the first two Anglo women—Narcissa Whiteman and Elisa Spaulding—present at a rendezvous.

Fur trapping in the 1830s

By the early to mid-1830s, it seemed that fur trappers were everywhere. In his thesis for Utah State University, Hadyn B. Call explained that the Santa Fe and other important trails were making it easier to get places, especially out West where much of the fur trade now flourished. Ewing Young, for instance, habitually traveled the Santa Fe several times, veering off regularly for trips as far as San Diego, Colorado, and Oregon. History Colorado reminds us that "this was a hard-scrabble business." Trappers still had to lug their trophies to rendezvous or eastern markets, and return west equally bogged down with supplies. Along the way they encountered rugged mountain trails, roaring rivers, unfriendly Natives, and scores of other hazards.

Obstacles, it seemed, lay around every corner. When Massachusetts merchant Nathaniel Wyeth hired a ship full of goods bound for the Columbia River in 1832, recounts Wyo History, he hoped to return with furs and make a fortune. On the way west, Wyeth stopped at the 1832 rendezvous, where "the bigger companies made it hard for him." And when he got to the Columbia, he discovered his ship and its valuable cargo had been lost at sea. And there was another problem: when artist Alfred Jacob Miller went to the 1837 rendezvous in Wyoming, he found low attendance. The fur trade was declining.

Why did the fur trade collapse?

Corporate greed descended upon the fur trade during the 1830s as fur companies began trapping as many beavers as they could, simply to out-do each other, confirms the Northwest Power and Conservation Council. Along the Columbia River area, the Bay Company was just one of many companies who failed to see that their greed was causing a serious decline in the animals. With 1840 in the near future, the fur trade began to collapse. Now too, according to Unframed, it was dawning on folks that the chemical treatment of mercury salts and acid to make the fashionable beaver hats was poisonous. Victims experienced what they called "hatters' shakes," but also blackened gums and tooth loss, drooling, muscle twitching and "a lurching manner of walking." This is where the saying "mad as a hatter" comes from.

Eventually, doctors and scientists began recommending gloves and clothing to protect the hatters, but it was too late. According to Bear Lake Rendezvous, silk fabric was found to be less toxic and less expensive than beaver. As the beaver population shrank and Prince Albert of England began favoring silk hats, the new fashion craze caught on, according to Hudson's Bay Company. "We are done with this life in the mountains," mountain man Robert Newell admitted to Jim Bridger, "done with wading in beaver dams, and freezing or starving alternately... The fur trade is dead in the Rocky Mountains, and it is no place for us now, if ever it was."

The mountain man in a new role

With the collapse of the fur trade, the trappers found themselves suddenly out of a job. Although buffalo robes were coming into fashion, according to Fur Traders & Rendezvous, the fur trade was officially over. Some mountain men, like Joe Meek, took to drink—to the extent that Meek's Nez Perce wife left him, taking the couple's 2-year-old child. Meek eventually got it together and was elected Oregon's first sheriff in 1843. Robert Newell proposed farming, also in Oregon. Still others found new jobs as scouts and Indian agents, according to San Bernardino County. Still others, says Oregon.com, helped establish missionaries along the Oregon Trail.

The plight of the mountain man's career also was relieved somewhat during the California Gold Rush beginning in January 1848. The fur trade was officially dead when gold was discovered at John Sutter's lumber mill near today's Sacramento. The rush attracted would-be miners from all over the world, including former fur trappers. Ten years later, according to Come to Life Colorado, fur trappers were among the thousands of prospectors who rushed to Colorado during the Pikes Peak Gold Rush. To the trappers, gold was perhaps easier than hunting for beaver—at least until they tried their hand at panning for gold in the frigid water of the Rocky Mountains.

What did the fur trappers leave behind?

The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that there were between 60 and 400 million beaver prior to European settlement of North America. After near extinction, a 1988 guesstimate puts them at six to 12 million. Long gone are the men who trapped them, but they did leave one important facet of America behind: their trails. As early as 1835, people were following the old trapper's trails as the only way to access the West. History confirms that explorers and fur trappers first blazed the "rough outlines" of the Oregon Trail.

On the other end of the spectrum, History also maintains that "it was the missionaries who really blazed the Oregon Trail," and that Nathan Wyeth led the first group of them west in 1834. This is true, but Wyeth did so as a trail-blazing fur trapper. Also, Digital History confirms that the mountain men are largely responsible for blazing "the great westward trails through the Rockies and the Sierra Nevada Mountains." In their day, one in five trappers died in their quest for fur. But those who survived were the most experienced at leading pioneers over the trails they had established and traveled so many years ago.