The Crazy True Story Of The New York Times

The New York Times is an iconic journalistic institution. Started as a penny paper in 1851, the Times has gone on to become one of the world's most prestigious and influential newspapers. It has won over 100 Pulitzer Prizes, three Peabody Awards, and served as a standard bearer for journalism for over 150 years.

When they began publishing in 1851, the paper's founders, Henry Jarvis Raymond and George Jones, envisioned a fair and objective newspaper. In their inaugural edition, they introduced themselves to the world by saying: "We shall be Conservative, in all cases where we think Conservatism essential to the public good;—and we shall be Radical in everything which may seem to us to require radical treatment and radical reform. We do not believe that everything in Society is either exactly right or exactly wrong;—what is good we desire to preserve and improve;—what is evil, to exterminate, or reform," via the New York Times.

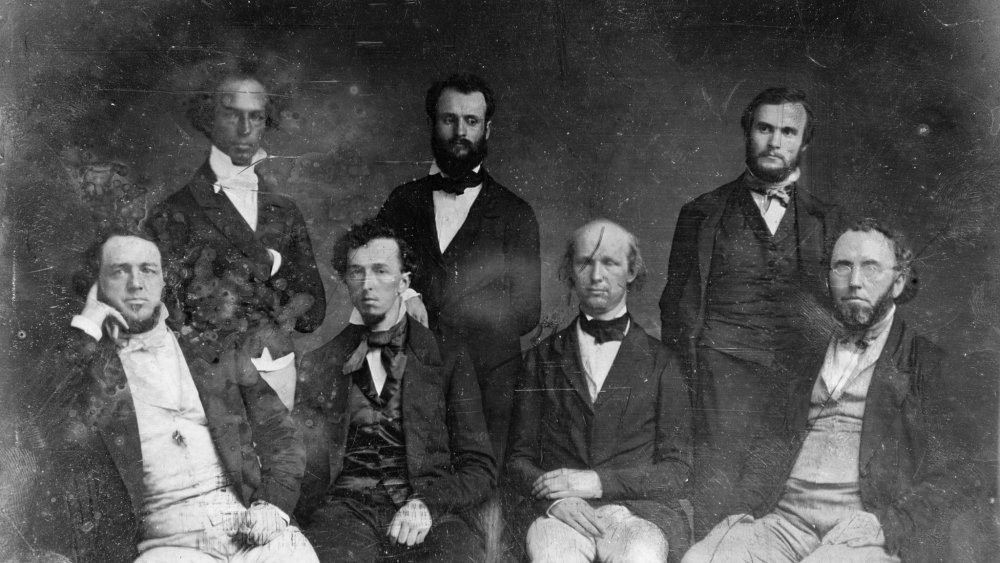

The New York Times founders met at the New York Tribune

In the 19th century, sensationalist journalism was the norm. Scandalous and salacious stories sold papers, and with 29 daily newspapers in New York alone, competition for readers was fierce. This type of reporting culminated in the 1890s, when the competition between William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal, and Joseph Pulitzer's newspaper, New York World, led to the coining of the term "yellow journalism."

However, a few decades earlier, two men had already set out on a mission to create a different type of newspaper. Henry Jarvis Raymond was a journalist and politician. Before being elected to the New York State Assembly in 1850, he had worked as a reporter and editor at the New York Tribune under its founder, journalist Horace Greeley, per Funding Universe. George Jones, another employee of Greeley's, met Raymond while working as a business manager at the Tribune. Tired of exaggerated stories, Raymond and Jones decided to partner up and create their own newspaper, one that would be objective and even-handed in its reporting.

Although Raymond was a prominent member of the Republican party — he is sometimes even referred to as the party's "godfather" — he wanted to move away from the open partisanship that was common at the New York Tribune, per The Jane Addams Papers Project. Jones and Raymond began planning their paper in 1843, but it would be several years before they were able to raise the necessary funds, per Britannica.

Henry Raymond personally defended the New York Times Building with Gatling guns

By 1851, Jones and Raymond had raised $70,000, and Raymond, Jones & Company was established in a brownstone on Nassau Street. On September 18, 1851, the first edition of The New York Daily Times was published, costing just a penny per copy. In their first edition, Raymond and Jones set forth their vision for the Times, declaring: "We shall seek... to promote the best interests of the society in which we live — to aid the advancement of all beneficent undertakings, and to promote...the welfare of our fellow-men," via the New York Times.

Within 10 days, they had a circulation of 10,000 copies, per Encyclopedia.com, and by 1852 their circulation had reached 24,000. In 1858, they settled into a new five-story building at 41 Park Row, on New York's famed Newspaper Row, alongside other newspaper titans like The New York Tribune and The New York World, per 6sqft.

Just a few years later, Raymond would be forced to defend 41 Park Row by force. By 1863, tensions over the Civil War were building, and on July 13, riots protesting the Union Army draft broke out in New York. Men began looting, burning, and destroying property. Newspaper Row, located near City Hall, was a prime target for rioters. Raymond and a few other men held off the mob by defending the building with Gatling guns, per the New York Times Archive. Deterred, the rioters instead attacked the New York Tribune building, sparing The New York Times from damage.

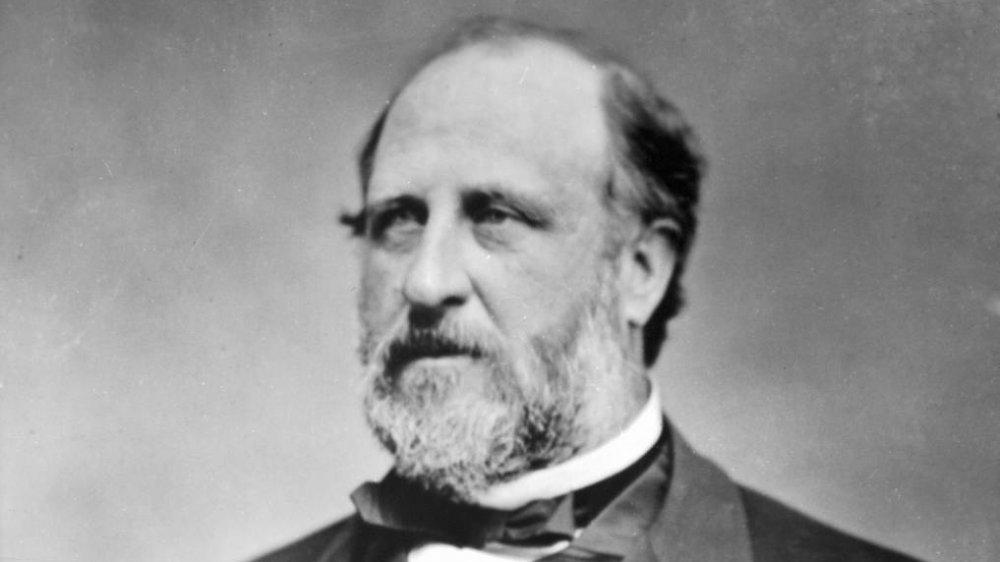

Jones refused a $5 million bribe

Raymond and Jones had established a successful working partnership. Raymond served as the paper's editor, while Jones managed the company's business affairs. However, when Raymond unexpectedly died in 1869, Jones assumed control of the editorial side of the paper, per Encyclopedia.com.

Under Jones' editorial leadership, the paper took on its first major political exposé: William "Boss" Tweed. Tweed had risen to the top of Tammany Hall, New York City's major Democratic political organization, in the 1860s. By the 1870s, Tweed and his gang of political cronies, known as the Tweed Ring, were dominating city politics. The Tweed Ring was openly corrupt, taking bribes, buying votes, and embezzling city funds, per History.

In 1871, Boss Tweed was embezzling money from inflated bills for construction on the city's courthouse. The Times began publishing a series of articles exposing how the money was really going to Tweed and his associates, per Cityroom. Tweed sent the controller, Richard Connolly, to Jones' office with a $5 million bribe. Jones refused, telling Connolly: "I don't think the devil will ever make a higher bid for me than that... but I should know that I was a rascal. I cannot consider your offer or any offer not to publish the facts in my possession." Instead, in July 1871, Jones started publishing excerpts transcribed directly from the controller's financial ledgers, under the headline "The Secret Accounts. Proofs of Undoubted Frauds Brought to Light. Warrants Signed by Hall and Connolly Under False Pretenses, " via Cityroom.

Boss Tweed tried to buy the New York Times

Furious, Boss Tweed tried to outright buy the Times from under Jones. The paper was financially vulnerable, since Raymond's death had left a significant amount of stock open for purchase. Jones himself only owned about 30 shares. To retain control of the paper, Jones enlisted the help of E. B. Morgan, the founder of Wells Fargo and one of Jones' business associates. Morgan bought 34 shares from Raymond's widow, which allowed Jones to retain control of the Times, per Encyclopedia.com.

Jones published an editorial in response to Tweed's attempted takeover, stating: "I have, from the first number of The Times, taken too active a part in its management, and feel far too deep a solicitude for its good name, to dishonor it by making it the advocate of mendacity and corruption. I pledge myself to persevere in the present contest under all and any circumstances that may arise," via Cityroom.

In November 1871, Tammany Hall was voted out of power, and almost every member of the infamous Tweed Ring was eventually arrested. Boss Tweed himself was arrested in 1873 and charged with forgery and larceny, effectively ending his political career, according to Biography. The Times reporting played an instrumental part in helping take down Tweed and his corrupt ring of cronies.

The Panic of 1893

Jones might have been able to prevent the Times from falling under Tweed's control, but by the mid-1880, the paper was in financial trouble. In 1884, Jones, in a departure from the paper's previous leanings, decided to publicly oppose the Republican party's presidential nominee, James G. Blaine, per Funding Universe.

This led to a drastic drop in readership, as Republican readers and advertisers pulled their support from the New York Times. The paper's profits suffered, and by the 1890s, the paper was in bad financial shape.

Jones passed away in 1891. Charles Ransom Miller, the paper's editor-in-chief, bought the remainder of Jones' shares in 1893, according to Encyclopedia.com. However, Miller was not a particularly adept businessman, and he was not cut out to weather the storm of declining readership, and the economic and political upheaval caused by the Panic of 1893, which caused stock prices to drop. Under his management, the paper's profits sank even further. He was forced to cut staff, which caused journalistic standards to decline, losing the paper even more readers. When the ensuing depression hit, the New York Times hit a new financial low, and by 1896, the paper was on the brink of declaring bankruptcy and closing its doors for good.

The rise of The New York Times Company

The paper's salvation came in the form of a group of Wall Street investors, who owned stock in the New York Times Publishing Company. Hoping to save their investment from financial ruin, the group of investors placed it into a receivership and recapitalized it under a new company, now called The New York Times Company. The investors paid out 2,000 shares of the new company in exchange for the old Times stock, per Funding Universe. One of the major stockholders was an editor and publisher from Chattanooga, Tennessee named Adolph Simon Ochs.

Ochs was a kind of journalistic Wunderkind, who had turned around the failing Chattanooga Times at just 20-years-old. He agreed to take over as publisher in exchange for the majority of the paper's stock, but there was a catch: The contract promised Ochs would become the majority shareholder only if he was able to make the paper profitable for three consecutive years.

On August 18, 1896, Ochs assumed control of the New York Times. He planned to "conduct a high standard newspaper, clean, dignified and trustworthy," per Encyclopedia.com. He also established the newspaper's famous motto: "All the News That's Fit to Print," which still appears on the upper left-hand corner of the front page today. However, Ochs' first few years as publisher were marked with more financial difficulty. The operations costs of covering the Spanish-American war were high, and a lack of capital made it difficult for Ochs to implement much-needed improvements to the paper.

The Titanic sinking led to soaring profits for the Times

As the nineteenth century neared its end, Ochs was facing a lot of pressure to turn a profit. His fellow executives proposed raising the price of the paper, which was then three cents per copy, to help offset the operations costs. Ochs, however, decided instead to lower the cost of the paper by one penny, hoping to attract more readers. His plan worked. The paper's circulation grew to 76,000 within one year, and by 1900, the paper was profitable, per Encyclopedia.com. On August 14, 1900, Ochs received controlling stock in The New York Times Company.

Ochs also hired veteran reporter Carr Vattel Van Anda away from the New York Sun, per Poynter, and it was Van Anda who was heading the early-morning news desk on April 14, 1912, when a bulletin came through announcing a steamship had struck an iceberg. The name of the steamship: the Titanic. Other editors approached the story cautiously. But Van Anda immediately published front-page headlines reporting the Titanic had sunk and directed every reporter on hand to focus on covering the disaster.

The next day, Van Anda dispatched his reporters to meet the Carpathia, which was carrying around 700 Titanic survivors, at the port at 9:30 pm. He carefully specified individual assignments to ensure every aspect of the story was fully covered. The Times had scooped the Titanic coverage, which greatly enhanced the paper's popularity and prestige.

World War I reporting earned the New York Times their first Pulitzer Prize

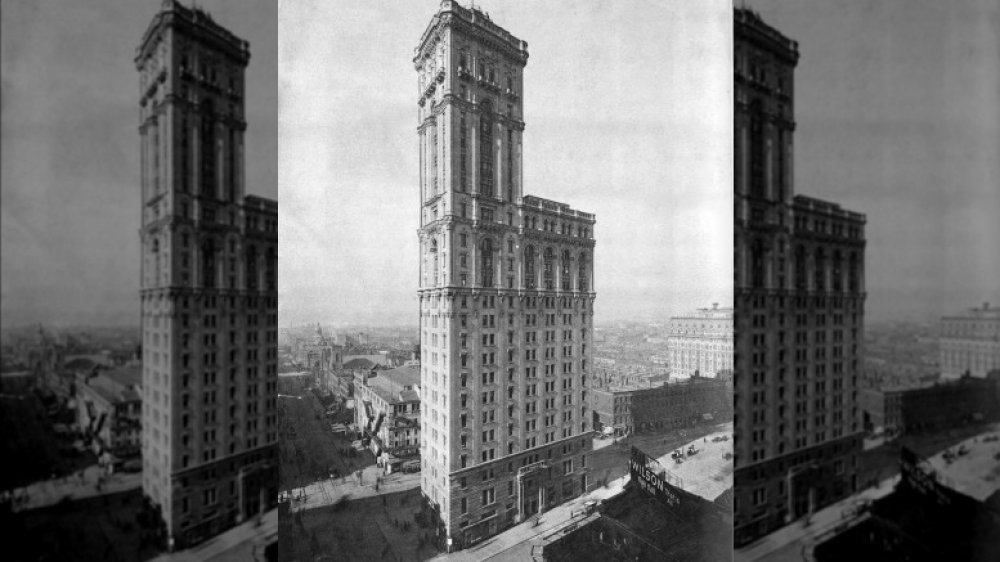

Under Ochs' leadership, the paper continued to grow. They relocated again, this time to a more prestigious building at 229 West 43rd Street, and the paper loaned its name to the city's iconic Times Square.

When the First World War began in 1914, the Times once again distinguished itself with its exceptional coverage of the conflict. In 1918, the paper earned its first Pulitzer Prize for public service, due to its publication of primary sources, documents, and speeches from World War I, per the New York Times Company. In the 1920s, the paper continued its success, while issuing at-times prophetic warnings about the state of the world, including foreseeing the rise of fascism in Italy and cautioning against the unsustainable economic excesses of the Roaring 20s.

When the Times' dire economics predictions proved correct, they were able to weather the crisis relatively unscathed. Ochs had been steadily reinvesting the paper's profits back into the company for years, so they were well-positioned to survive the downturn when it finally struck. Throughout the Great Depression, the paper maintained a daily circulation of around 500,000, per Funding Universe. Unfortunately, Ochs' steady leadership came to an end on April 8, 1935, when he passed away.

The New York Times during World War II

Arthur Hays Sulzberger, Ochs' son-in-law, assumed the position of publisher on May 7, 1935, heading the Times as the country entered World War II.

In 1942, two Times reporters were captured and held as prisoners of war. Harold Denny, charged with covering the Afrika Korps, was kidnapped by Nazis in Tobruk. He was held for five months and forced to undergo repeated questioning by the Gestapo in Berlin. Another reporter, Otto D. Tolischus was held, tortured, and accused of being a spy while covering the war in Japan. While Denny and Tolischus were both eventually released, the Times did suffer casualties during the war. Byron Darnton, another war correspondent, died in a bombing off New Guinea, when an American B-25 bomber mistook his ship for a Japanese ship, per the New York Times Company. Darnton was the tenth American reporter to be killed in World War II.

Following the war, Sulzberger expanded the paper to include an international edition, expanded the paper's financial coverage, and even started running the Times crossword in 1942. The New York Times Company also acquired two New York City radio stations after the war, WQXR and WQXR-FM. By 1958, the company had been steadily increasing profits for 60 years, per Funding Universe, but by then Sulzberger was in poor health. He retired from the paper in 1961, and his son-in-law, Orvil E. Dryfoos, succeeded him as president and publisher.

New York Times v. Sullivan

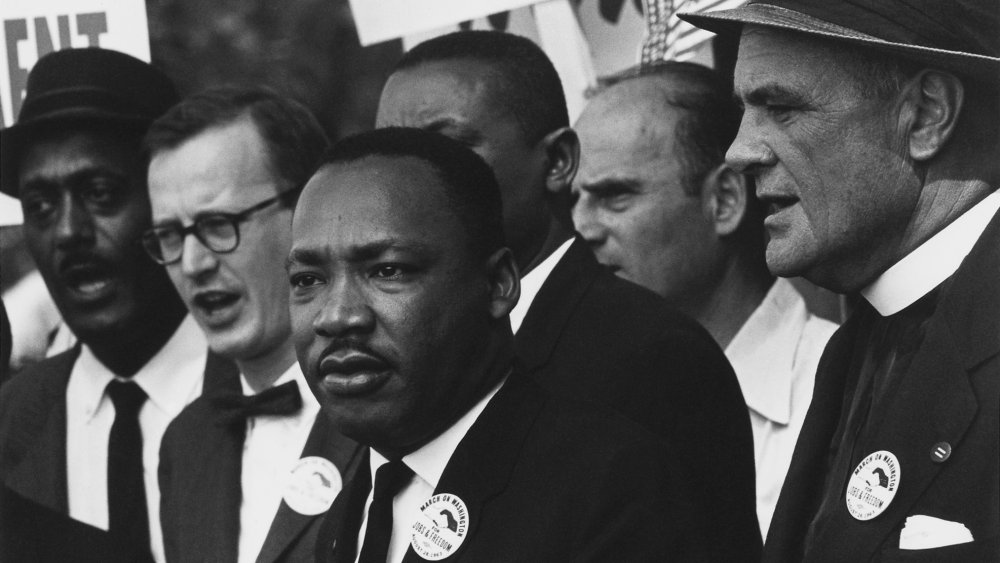

In the 1960s, the Times became embroiled in a landmark libel case that would have lasting repercussions for the fate of free press. In 1964, civil rights leaders took out a full-page ad in the New York Times, soliciting contributions to the defense fund of Martin Luther King, Jr. The paper ran it, but some of the ad's text contained exaggerations and inaccuracies. For example, the ad included the phrase: "When the entire student body protested to state authorities by refusing to re-register, their dining hall was padlocked in an attempt to starve them into submission," via the Bill of Rights Institute, which proved to be false.

Montgomery Public Safety Commissioner, L.B. Sullivan, sued the Times for libel, claiming the ad implicated him, although he was not mentioned by name. When Sullivan won the case in an Alabama court, the Times was ordered to pay $500,000 in damages, per Oyez. The Times appealed, and the case went to the United States Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court unanimously ruled in favor of the Times, declaring that in libel cases the plaintiff must prove that the publisher knowingly published false statements with reckless or malicious intent. According to Justice Brennan, "actual malice–that is... knowledge that it was false" had to be proven in order to win a libel suit against a newspaper, via the Bill of Rights Institute.

The Pentagon Papers

In 1971, the Times went to the United States Supreme Court again, this time against the administration of the President of the United States. Daniel Ellsberg, a former State Department employee, had leaked classified documents from the Department of Defense to Times reporter Neil Sheehan. The documents contained highly classified details pertaining to the government's diplomatic and military involvement in the Vietnam War. The Times began publishing excerpts from the documents on June 13th, 1971.

Almost immediately, the Nixon administration brought the case to the Supreme Court. Nixon demanded the Times cease publishing the leaked documents, claiming that classified government material should not be made available to the public. However, the Times argued the papers fell under the "people's right to know," via History.

On June 30th, 1971, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Times. According to the ruling, the First Amendment protected the paper's right to publish the documents. The paper continued to publish what became known as the "Pentagon Papers," causing the American public, who were already souring on the Vietnam War, to further oppose the United States' involvement in Vietnam. The Times earned another Pulitzer Prize in 1972 for their publication of the Pentagon Papers, per Britannica.

'Send in the Troops'

The New York Times has seen its share of controversies over the course of its 168-year history. In 2020, the Times came under fire for publishing an Op-Ed by Republican Senator Tom Cotton, regarding the nationwide Black Lives Matter protests that had sprung up in response to the death of George Floyd while in police custody on May 25th, 2020. In his Op-Ed, Cotton called for the use of military forces to "restore order" to cities that have been rocked by ongoing violent protests. Denouncing the "orgy of violence in the spirit of radical chic," Cotton called for implementing the Insurrection Act, which "authorizes the president to employ the military 'or any other means' in 'cases of insurrection, or obstruction to the laws,'" via the New York Times.

The backlash was immediate. The piece was met with anger and criticism, with the public denouncing Cotton's call to use military force on the American people. Even some Times employees went to Twitter to criticize the piece, saying "Running this puts Black @NYTimes staff in danger," via Vox.

Following its publication, James Bennet, the Op-Ed editor, resigned from his position, and the section's deputy editor, Jim Dao, was reassigned. While the piece has not been taken down, the Times included an Editor's Note to the piece, saying "we have concluded that the essay fell short of our standards and should not have been published," via the New York Times.