The Ugly Truth About Mount Rushmore

Since before the United States was knee-high to a bald eagle, one person's majestic monument has been another's symbol of suffocating tyranny. Mere hours after Americans declared their independence in 1776, "a mob of soldiers and sailors" swarmed Lower Manhattan and toppled a gilded statue of King George III. Later, the dethroned metal monarch was partially melted down into 42,000 musketballs that some dubbed "melted majesty," via National Geographic, and used by Patriot soldiers against Redcoats during the War for Independence. Because, what better way to take aim at a king, than to aim him at his own army?

Here's where things start to get awkward. The biggest hero of the War of Independence and one of America's dearest presidents, George Washington, now forms part of what's basically a much worse version of a statue to King George — one that remains un-toppled, and possibly tops the list of ironic icons of American freedom. That icon is Mount Rushmore, the mountainside monument honoring Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln. Carved into the Black Hills of South Dakota, it's arguably a sixty-foot tall slap in the face of the Sioux and Arapaho people who laid claim to that land with the U.S. government's blessing.

Gold Rushmore

With people toppling and decapitating statues of Christopher Columbus and NASCAR slamming the brakes on the Confederate flag, criticizing Mount Rushmore might seem to some like a bridge too far, a bridge that will be burned by the pyromaniac fervor of a cancel culture with access to matches and gasoline, without a single firefighter in sight. Can't people just forget about all the bad parts of history to avoid erasing the stuff we want to remember? Is nothing sacred anymore?

Well, the Black Hills are totally sacred to the Sioux, but the U.S. stole them anyway.

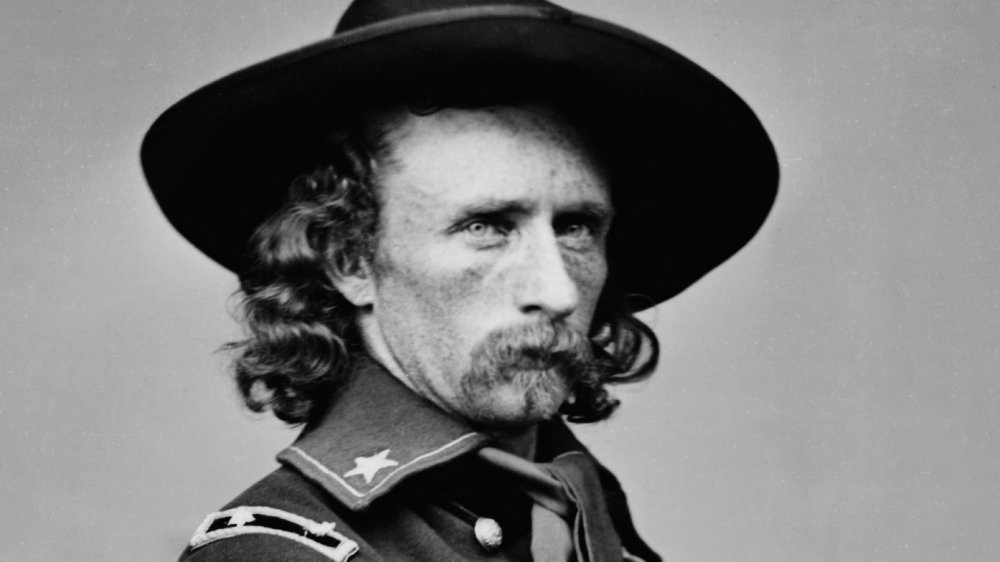

Smithsonian Magazine explains that in 1868, the U.S. ratified the Fort Laramie Treaty with the of Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota peoples collectively referred to as the Sioux and the Arapaho. That agreement specifically set aside the Black Hills as "unceded Indian Territory," making it off limits to Americans. But as Black Hills Visitor details, in 1874, then-Lieutenant Colonel George Custer discovered gold, inciting a rush of U.S. settlers and prospectors who illegally raided the land. The U.S. Senate, intent on dishonoring the terms of the treaty, offered to buy the Black Hills for $6 million. But to the Sioux and Arapaho, this place was priceless. So the government resorted to force, leading to a series of bloody conflicts.

Rubbing salt in the wound

The war for the Black Hills led to the legendary Battle of Little Bighorn, where Crazy Horse galloped to victory, crushing Custer's forces in June 1876. That September, the American Empire would strike back during the Battle of Slim Buttes, better known to some Lakota as "The Fight Where We Lost The Black Hills." They would suffer more devastating losses as the U.S. government relegated them to reservations.

In 1890, reservation police killed revered spiritual leader and Sioux chief Sitting Bull, who had famously rallied tribes in the fight to preserve the Black Hills, via History. This was followed by the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre, when U.S. troops slaughtered 150 Lakota Sioux, about half of whom were women and children, on South Dakota's Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Robbed of their land, their leaders, and their lives, the Sioux would see their sacred Hills defaced by the faces of presidents when construction of Mount Rushmore commenced in 1927.

In 1980, the Supreme Court ruled that the U.S. had illegally grabbed Black Hills and awarded the Sioux "$100 million (over $1 billion in 2018 money) as reparations, according to Smithsonian Magazine. But the Sioux refused the money because they never intended to sell their hallowed hills. Per USA Today, in 2020, Oglala Sioux President Julian Bear Runner called for the removal of Mount Rushmore, calling it "a great sign of disrespect."