The True Story Behind Nosferatu

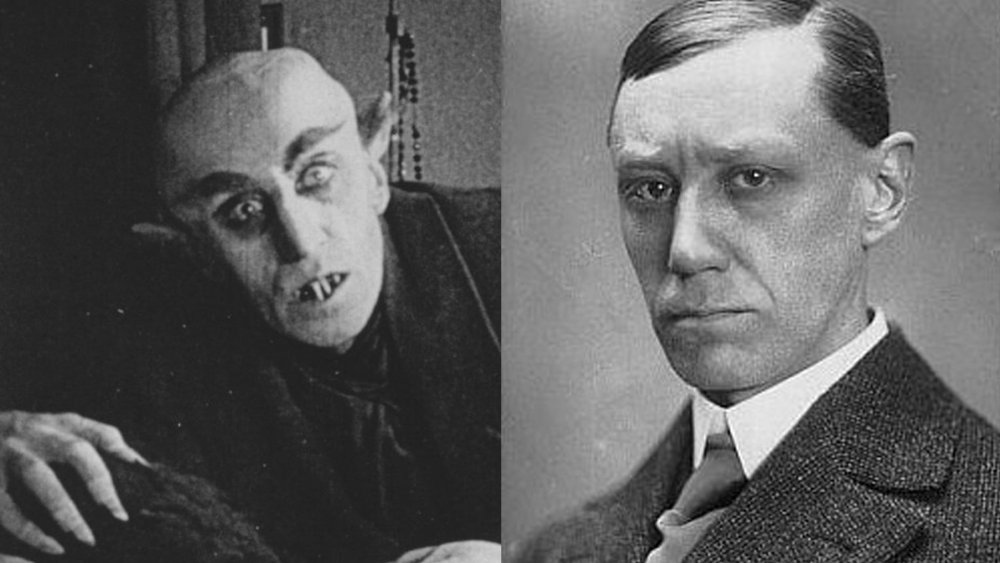

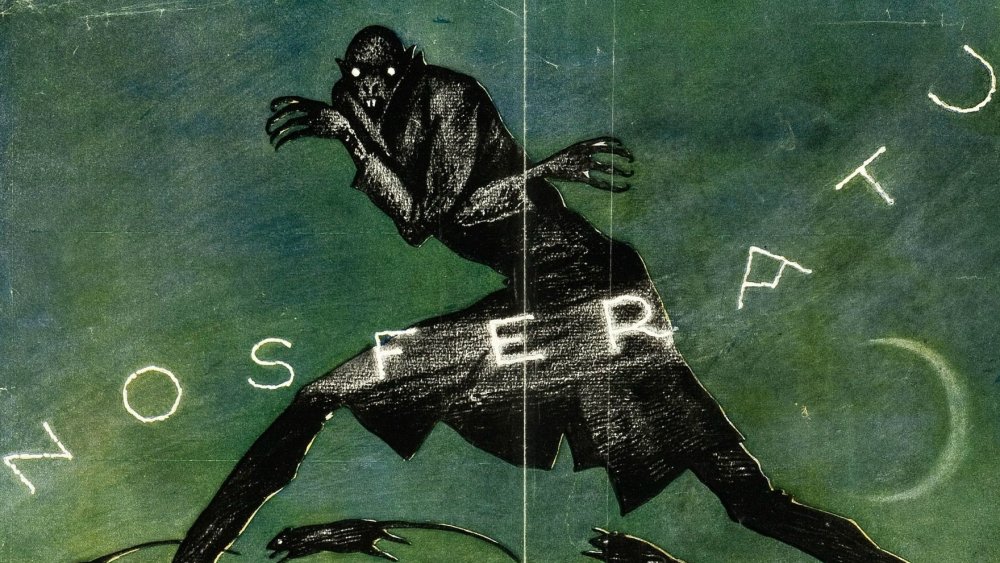

In the horror genre, few, if any, movies are as iconic and revered as F.W. Murnau's 1922 silent vampire tale Nosferatu. Brimming with dread and atmosphere, the film is an example of how even the primitive moviemaking of cinema's early days can yield breathtaking results that stick with the viewer forever. More so, the film's villain Graf Orlok, portrayed by German actor Max Schreck, has become a timeless and gut-wrenching interpretation of the vampire, offering those who grew up with the cliched flowing evening wear and smirking arrogance of Bela Lugosi's Dracula an uglier, more haunting interpretation of the undead.

But like any movie worth its salt, Nosferatu was a nightmare to make. The film's production was plagued by financial and legal issues, nearly ruining the lives of some of the people who made it. That we even have the movie at all is a miracle, given that every copy of Nosferatu was ordered destroyed by the German courts. But the film remains a dark classic, exciting cinema fans to this day — and lending an odd sort of validation to the real-life circumstances behind its creation...

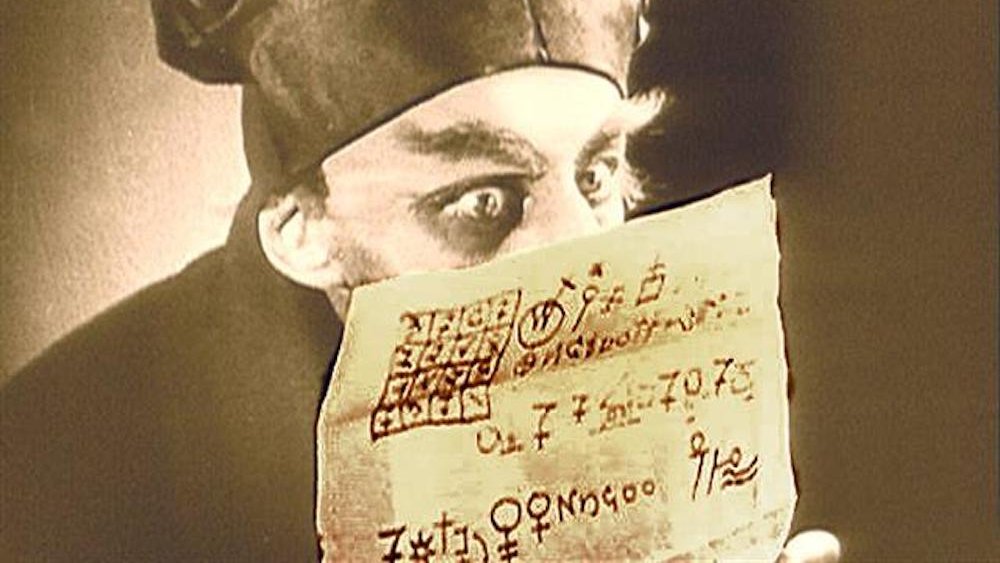

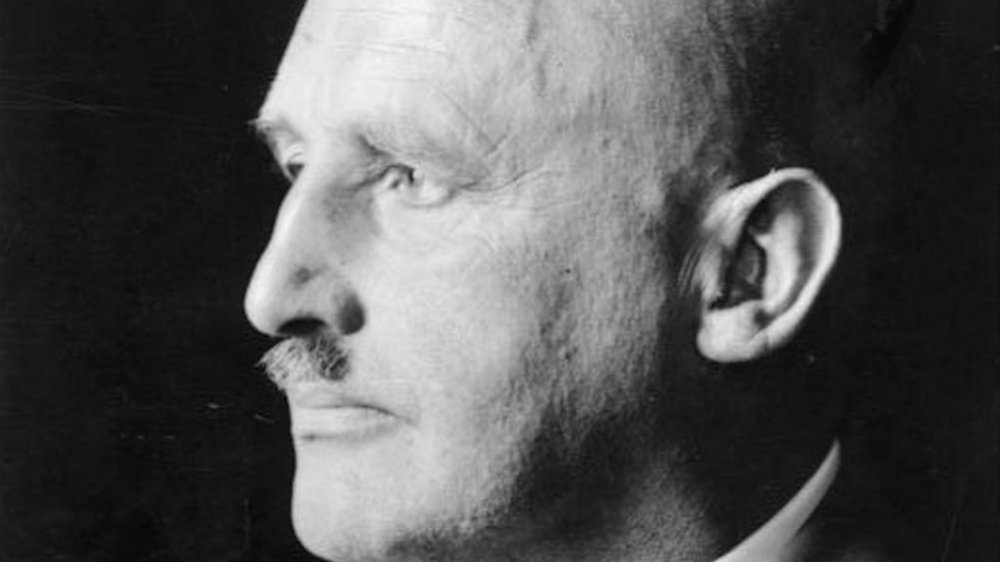

Nosferatu's producer was a German occultist

German director F.W. Murnau is most often credited for Nosferatu's unique atmosphere and imagery, and rightly so — Murnau would go on to massive success for films like 1924's The Last Laugh, 1926's Faust, and 1927's Sunrise. But equally deserving in praise for the film is Albin Grau, Nosferatu's producer — and an experienced occultist. According to PeoplePill.com, Grau was a member of a hermetic order named Fraternitas Saturni (Latin for "Brotherhood of Saturn," referencing the Roman god of time, the harvest, and death), where he used the magic name "Master Pacitius." The order was founded in the 1920s in Germany by Eugen Gorsch.

Many believe it was Grau's spiritual relationship with the occult that leant Nosferatu its chilling ambiance. One can even see hermetic and occult symbols in certain scenes of Nosferatu. When Grau started the production company which made the film (named Prana Film after the Buddhist concept of "prana," meaning "breath" or "life force"), it was meant to focus on films solely of a spiritual or supernatural nature.

Producer Albin Grau wanted to make a vampire film before reading Dracula

Many critics will point out that Nosferatu is a rip-off of Dracula. And to be fair, that's exactly what it is. Before the widespread popularity of Bram Stoker's novel, vampires were folk legends rather than part of pop culture. But apparently, while Albin Grau wanted to film Dracula, he had become interested in vampires even before reading the novel, when he was stationed in Serbia during World War I.

According to a 1921 article by Grau in Buhne und Film, partially reprinted by vampire research site Shroudeater.com, a Serbian farmer told the producer that his father had become a vampire. The farmer's father had died and was buried without receiving the holy sacraments. A month later, a string of deaths occurred — and then witnesses reported seeing the farmer's father walking around. Locals exhumed his coffin and found it empty. The next morning, they returned and found a healthy-looking man with teeth so long and pointy that he couldn't close his mouth. A stake was driven through the corpse's heart before it was cremated.

While Grau's story might have been a way to drum up hype for his film, Eastern Europe has always been where the legends of vampires as we know them — the blood-drinking, nocturnal undead — have originated. According to National Geographic, the country was home to some of the earliest European vampire hysteria, in part focused around the folkloric character Sava Savanovic. That Grau would have heard this story in Serbia makes sense.

Character names were changed because the studio hadn't obtained the rights to Dracula

Though Nosferatu's creators gave their central vampire a look and feel all its own, many contend that the plot — a young clerk traveling to the old country, only to discover a vampire nobleman who covets his beloved — is just Bram Stoker's Dracula with the names changed. This is quite literally true – Nosferatu was adapted from Dracula, but the characters' names were altered for the simple reason that producer Albin Grau couldn't obtain the rights for the novel from Stoker's estate, according to a piece in Plagiarism Today.

According to Forward, the job of trying to dodge litigation fell on screenwriter Henrik Galeen. He changed names, settings, descriptions, and even the cast of the story in order to avoid litigation and adapt Stoker's lengthy epistolary novel into a silent film. Count Dracula became Graf Orlok, Jonathan Harker became Thomas Hutter, Renfield became Knock, and Mina Harker became Ellen Hutter. Many of the novel's supporting characters, such as Professor Van Helsing and cowboy Quincy Morris, are absent entirely. Unfortunately, the writer's hard work was not enough to keep Prana Film out of legal hot water.

The actor playing Nosferatu was a loner whose name meant "terror"

The actor playing Graf Orlok, one Max Schreck, has been the subject of rumors over the years. The most common one is that he was, in fact, a vampire himself, a concept that was turned into the full-length horror film Shadow Of The Vampire, starring Willem Dafoe as the undead Schreck. While the story is obviously untrue, everything about Schreck did little to dispel these rumors.

According to an interview with biographer Stefan Eickoff in Reuters, Schreck was no supernatural creature but rather a versatile actor with an unusual temperament. He was a civil servant's son with over 800 screen and stage roles and was "a loyal, conscientious loner" with no family to speak of. Schreck was also known for his detached, offbeat sense of humor, leading one of his contemporaries to claim that he lived in his own "remote and strange world." Of course, it certainly didn't help his reputation that the word "schreck" is German for "terror," immediately painting the man as an intimidating figure.

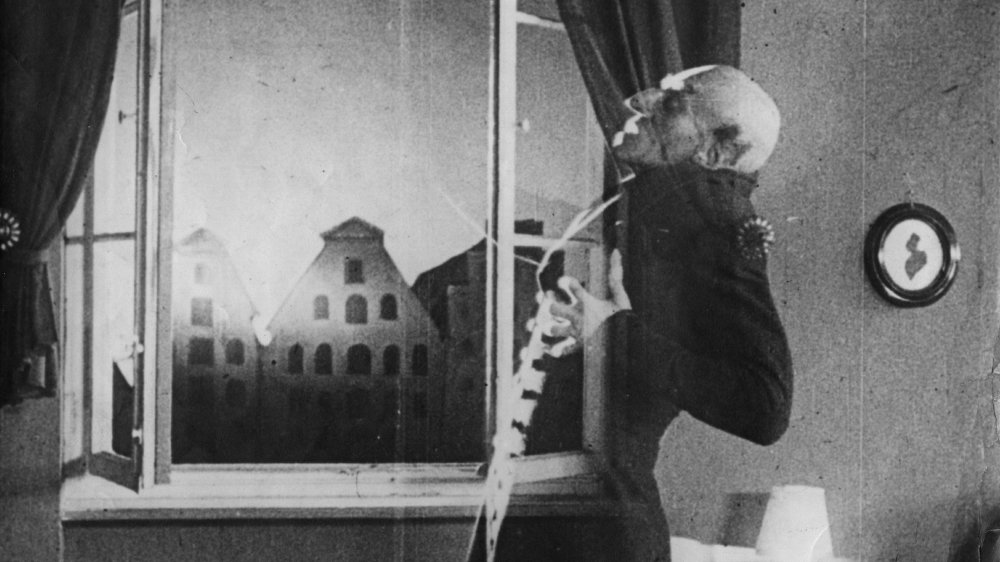

Nosferatu single-handedly created the trope that sunlight kills vampires

While different depictions of vampires cherry-pick their strengths and weaknesses — fearing the crucifix, casting no reflection in mirrors, transforming into bats — one of the universally recognized tropes is that vampires are killed by direct sunlight. However, this wasn't always a common concept. In fact, Bram Stoker's Count Dracula walks around in the sun — he's merely weakened by it.

It was Nosferatu's climax that cemented the idea of sunlight killing the vampire into the minds of the public. As noted in a piece on Medium, it was F.W. Murnau who came up with the idea of the vampire being disintegrated by the rays of the dawn. While the poetry of the final scene is laid on thick — the viriginal Ellen Hutter sacrifices herself to the vampire, so that he, drunk on her innocent blood, doesn't notice the rising sun until it's too late — truthfully, the use of this special effect was just a cheap alternative to a grisly death scene. The folkloric way to dispense with a vampire involved driving a stake through its heart, cutting its head off, and burning the corpse, which wasn't easy to show onscreen.

The Medium piece does make a good point, though: Nosferatu wasn't widely viewed after its release due to it being destroyed via court order. So whether the sun as vampire repellent spread quickly among the few folklore enthusiasts who saw the film, or whether Murnau had heard about it in some rare piece of lore, is unknown.

Nosferatu's premiere involved an elaborate costume party at the Berlin Zoo

For a work of art as atmospheric and macabre as Nosferatu, Grau and Murnau couldn't simply host the world premiere in a movie theater. Instead, the film was premiered with the kind of event one wishes more horror movies launched with — an epic costume party at a zoo.

According to Mental Floss, Nosferatu premiered March 4, 1922, at the Marble Hall of the Berlin Zoological Gardens. Before the film, there was a stage show including a spoken-word prologue by star Max Schreck himself, followed by a dance number. After the showing, there was an elaborate masquerade ball, complete with gowns, frocks, and suitable costumes to honor such a morbid film. The party, dubbed "Das Fest des Nosferatu" ("The Festival of Nosferatu") raged until 2:00 AM, with guests including German filmmakers like Ernst Lubitsch and Heinz Schall. As noted by Brenton Film, the party and promotional campaign surrounding the film cost more than the movie itself.

Thankfully, this elaborate event has been recreated to a certain degree today. Austin, Texas, hosts an annual Nosferatu Festival, inviting fans from all over the world to travel to America's "City of Bats" and celebrate all things vampiric.

Hitler's top journalist saw Nosferatu as an anti-Semitic epic

Given the climate of anti-Semitism in Europe during the first third of the 20th century, it's unsurprising to learn that many saw Nosferatu as an inherently anti-Semitic film. Jews had for some time been cast as blood-drinking witches by anti-Semites, and the similarities between the vampire Graf Orlok and contemporary stereotypes of Judaism — the long nose, rat-like features, and hunger for innocent Germanic women — lent the movie a bigoted undertone.

One member of the audience at Nosferatu's premiere leaped on this concept: Julius Streicher, who would become chief editor of Hitler's antisemitic newspaper Der Stürmer. According to an article from the blog of the Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot, Streicher was so transfixed by the film that he returned to watch it repeatedly. Later on, in the pages of Der Stürmer, Streicher would repeatedly use art and prose to conflate Jews with vampires, making Jewish people out to be rat-faced, bloodthirsty plague-spreaders.

While it has since been noted that F.W. Murnau was friendly with many Jewish people in the film industry, the feeling that Nosferatu was made to stoke the fear of the universal Other — a claim often made about Dracula as well — remains to this day.

Bram Stoker's widow sued to have Nosferatu destroyed -- and won

Nosferatu was a direct adaptation of Bram Stoker's novel Dracula, with names and references changed to avoid a copyright infringement lawsuit. Unfortunately, the makers of the film weren't ready for the sheer tenacity of the enemy they had made: Florence Balcombe, Stoker's widow.

According to David J. Skal's book Hollywood Gothic: The Tangled Web of Dracula From Novel To Stage and Screen, Balcombe was an "English rose"-style beauty who'd once been courted by influential public figures such as Oscar Wilde. After her husband's death, her only real source of income was the royalties from Dracula, his one truly successful book. When she discovered that Grau and Murnau had made the film, she demanded financial compensation — when they dodged this, she demanded that all copies of their film be destroyed.

Despite Nosferatu's producers doing their best to avoid Balcombe's wrath, Stoker's widow won. The German courts ordered all prints and negatives of Nosferatu to be burned, in one of the first cases of capital punishment being waged against a film. However, by then, copies of the movie had been distributed throughout the world, and as one can guess, the fact that Nosferatu is such an iconic film means that it was not entirely lost.

Nosferatu's production company declared bankruptcy to avoid litigation

Though Nosferatu is considered a cinematic milestone today, at the time, it was a risky moneymaking venture that had cost a ton to promote. When Bram Stoker's widow decided to take legal action against Prana Film, producer Albin Grau had only a few options when it came to avoiding lawsuits. So he chose one of the extreme ones — and declared bankruptcy.

Prana Film's finances had always been precarious, but the threat of litigation — and one with actual merit behind it, given Grau's decision to simply make Dracula with the names changed — would have been too much for the production company to bear. According to ScreenPrism, Grau's declaration of bankruptcy made Nosferatu the only feature Prana Film would ever make. Meanwhile, TCM says that Grau sold the movie to Deutsche Film Produktion in order to immediately distance himself from the production.

Different versions of Nosferatu exist around the world

Even after Stoker's widow ordered Nosferatu destroyed, the film managed to live on. By that time, copies of the movie had been sent to theaters around the world. Meanwhile, TCM notes that after Grau sold the film to Deutsch Film Produktion, the company edited it without Murnau's permission.

The result is that many of the copies of Nosferatu that survived were incomplete, re-edited, or had their title cards changed, so every version of the film is different. As reported by Fictosphere, one such unique copy was The Twelfth Hour: A Night Of Horror, a sound version of the film released in 1930 by Deutsche Film Produktion. Featuring new scenes, a different ending, the inclusion of footage that didn't make the original film, and even a different actor playing the vampire in similar makeup, The Twelfth Hour was shown in theaters and on television around the world but is now difficult to find and stands as a testament to how original movies were recut and re-released before the art form was commonplace.

Interestingly enough, even Bram Stoker's widow couldn't kill the vampire after she'd ordered it burned. According to David J. Skal's Hollywood Gothic, shortly after she'd won her case against Nosferatu, Florence Balcombe received an invitation to a private film society screening — of F.W. Murnau's Dracula.

Renowned critics consider Nosferatu better than any official Dracula film

At the end of the day, the most iconic depiction of Dracula will always be Bela Lugosi in Todd Browning's 1931 film by Universal — the cape, the widow's peak, the thick Eastern European accent. And yet, for many film critics, Nosferatu's ugly, ethereal depiction of the vampire makes it a superior film to its latter-day, properly licensed descendants.

In fact, renowned film critic Roger Ebert gave the movie four out of four stars, saying on his website, "To watch F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu (1922) is to see the vampire movie before it had really seen itself. Here is the story of Dracula before it was buried alive in cliches, jokes, TV skits, cartoons, and more than 30 other films. The film is in awe of its material. It really seems to believe in vampires.

"'Nosferatu' is a better title, anyway, than 'Dracula,'" he adds. "Say 'Dracula' and you smile. Say 'Nosferatu' and you've eaten a lemon."

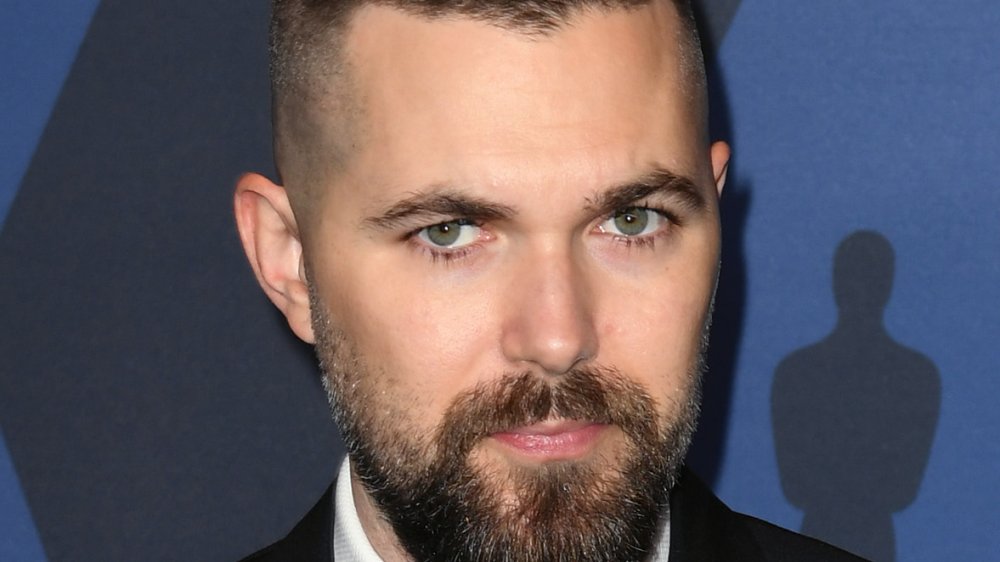

A remake of Nosferatu is on its way

Nosferatu has been directly remade once — German documentarian Werner Herzog directed infamous character actor Klaus Kinski as Count Dracula in 1979's Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht. Also, Willem Dafoe played the secretly vampiric Schreck in 2000's Shadow of the Vampire, while an especially terrifying 1993 episode of Nickelodeon's Are You Afraid Of The Dark? depicted Nosferatu leaping off the screen and haunting an old marquee theater.

However, it appears as though a new version of Nosferatu is in the works. According to Bloody Disgusting, Robert Eggers, director of stark psychological horror films The Witch and The Lighthouse, is planning a remake of F.W. Murnau's classic film. The director has stated that he is drawn to the movie for its primordial depiction of the vampire, as well as for producer Albin Grau's occultist vision.

"I think Nosferatu is closer to the folk vampire," says Eggers. "The vampire played by Max Schreck is a combination of the folk vampire, of the literary vampire that actually has its roots in England before Germany, and also [has roots in] Albin Grau, the producer/production designer's occultist theories on vampires."