The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Bela Lugosi

Once in a full moon, an actor portrays a villain with such flare that fans have a hard time separating the man from the character. Think Ralph Fiennes as Voldemort, Dolph Lundgren as Ivan Drago, and Jack Nicholson as the Joker. Or Heath Ledger as the Joker. Or Joaquin Phoenix as the Joker. You get the point.

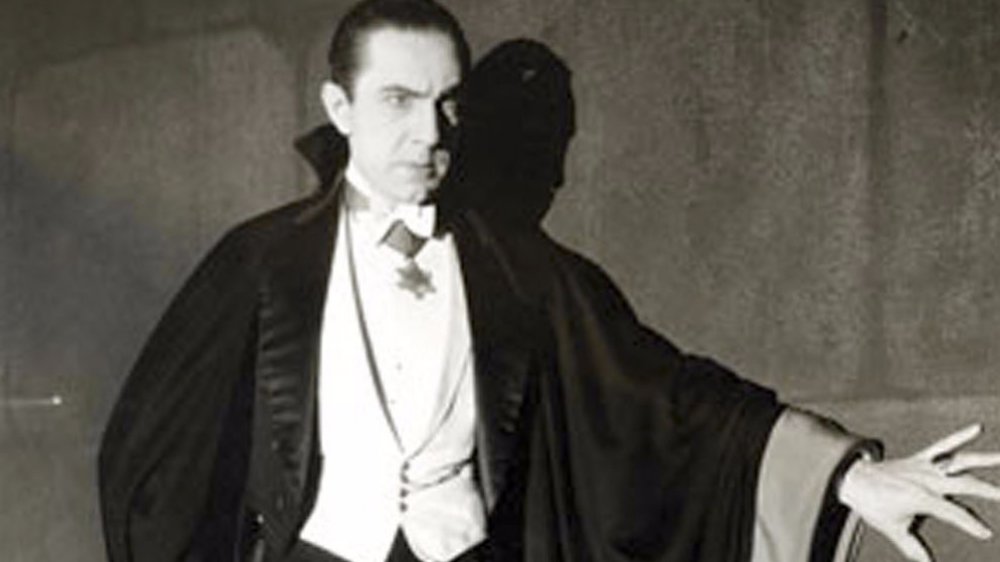

The Hungarian actor Béla Ferenc Dezső Blaskó, better known as Bela Lugosi, became known to many as the face of Dracula after his iconic appearance as the famous vampire in the 1931 film adaptation of Bram Stoker's classic novel. It turned out to be both a blessing and a curse. Lugosi, who got his start acting in Shakespearean dramas in his native Hungary, was an ambitious and stately performer. He'd hoped, like his contemporary, Boris Karloff, to win the hearts and minds of not just fans but critics, too. Instead, he was relegated to the horror genre, written off as a B-movie hack.

Everywhere Lugosi went, people saw a blood-sucking bad guy from Transylvania. It didn't help matters that money was often tight. Financial difficulties forced him into taking roles that were beneath both his talent and pay grade. Much like that of the vampire he brought to life, Lugosi's story is a fascinating one, full of ups and downs and twists of fate. Read on for more on this caped legend of stage and screen. If you dare...

The untimely death of Bella Lugosi's father was a life-changer

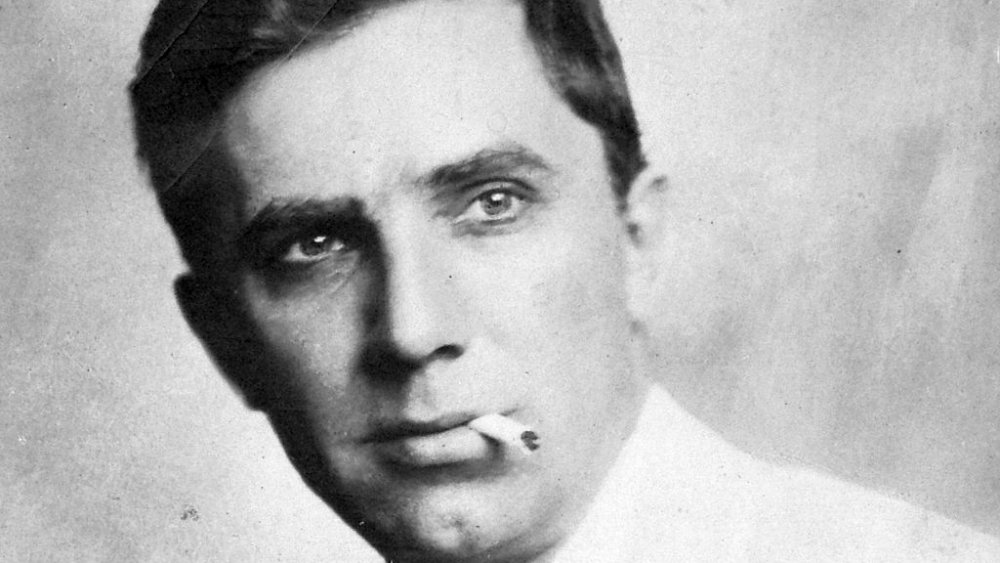

Bela Lugosi grew up in a solidly middle class family in Hungary, the son of a baker-turned-banker. According to the biography, The Immortal Count: The Life and Films of Bela Lugosi, Lugosi's father, Itsvan, was a prosperous man who left the baking profession in 1883 to set up, with the help of a few partners, a small savings bank in the town of Lugos. The young Bela was born just the year before. Itsvan, a strict and conventional man, had high hopes for his son, but Bela struggled in school and, when asked what profession he hoped to pursue in the future, he answered, "highway bandit." Not exactly a natural fit for a banker's boy.

Itsvan died when Bela was just 12-years-old, throwing the family fortunes into turmoil. Lugosi later told reporters that he had no choice but to leave his home to find a job, walking 300 miles to an industrial center where he worked as a miner. As this piece in American Ghost Stories, points out, Lugosi wasn't always truthful about his past — he was prone to exaggeration, claiming in one 1941 interview to have stolen 700 hats as a young boy — but his childhood was undeniably cut short by his father's death, propelling him into menial labor jobs that tested his mettle.

Bela Lugosi was a man without a homeland

As a youth, Béla Blaskó dreamed of becoming a stage performer, but his uptight, middle class family disapproved of the profession. Unable or unwilling to finish his studies, he supported himself as a miner and railroad worker until the age of 18 when his sister, Vilma, persuaded her husband to secure Bela a place in a traveling theater troupe. Lugosi's life as an actor had begun. It was not immediately successful, though. As this biography notes, he was fired from gigs roughly 20 times over the next two decades for incompetence. He was learning to act by trial and error, or, as he put it, his will "was forged to whiter and whiter heat." The heat clearly worked. He was eventually invited to join the National Theater of Budapest.

Shortly thereafter, according to this profile in Workers World, he had to leave Hungary for German because his left-wing sympathies were not tolerated when Hungary's short-lived communist government was overthrown in 1919. It was a wrenching move for the rising star, who, 16 years earlier, had changed his surname from Blaskó to Lugosi in homage to Lugos, the city of his birth.

Bela Lugosi's greatest triumph was also his doom

Having spent a year acting in silent films in Germany's Weimar Republic, Lugosi traveled to America on a merchant ship in 1920, landing in New Orleans before heading north to New York City. He didn't know a word of English at the time, but that didn't stop him from auditioning, and, two years after his arrival in the States, he was cast in the play, The Red Poppy. It was his first English-speaking role. According to SyFy Wire, he learned the language bit by bit, role by role, reading his lines out loud to himself.

In 1927, he got his big break. The biggest break, really. Following a successful run as Count Dracula in the stage version of Bram Stoker's bloody tale, Lugosi was cast as the lead in the film adaptation. The fact that he was born just 50 miles from where the novel is set made him a natural choice for the part. He wasn't Universal Pictures' first choice, though. That honor went to Lon Cheney. Then Cheney died, and Lugosi replaced him on the bill.

It was both the fulfillment of a dream for Lugosi and, as this look at his career in Naked History suggests, the beginning of a nightmare. Following the blockbuster release of Dracula in 1931, the striving and serious actor from Transylvania would find himself typecast again and again by Hollywood, passed over for more meaty roles and given, almost without fail, the part of the cheesy villain.

Bela Lugosi was a count two times over

If Lugosi hoped that the success of Dracula would allow him to emerge from the gentleman vampire's — ahem — shadow, he was sorely mistaken. Not only did the role take over his life; it subsumed his very identity.

When it was clear the film was going to be a monster at the box office, the over-heated publicity department of Universal Studios got busy concocting a backstory for Lugosi worthy of Bram Stoker. Gone were Lugosi's middle class parents, his teenage struggles to make ends meet in the mines and rail yards of turn-of-the-century Hungary. In their place was a count's pedigree and a castle in the mountains of Transylvania. According to the Imaginative Conservative, the erasure of Lugosi's actual history was just one unfortunate blow he had to survive, following his star turn as the count. The article quotes Lugosi as saying, "Never has a role so influenced and dominated an actor's life as has the role of Dracula. He has, at times, infused me with prosperity and, at other times, he has drained me of everything... It's a living, but it's also a curse... It's Dracula's curse."

Interestingly enough, Vlad the Impaler, Broker's inspiration for the count, was likewise a misunderstood man. He might have been a bit blood thirsty, but he was a hero, too.

Bela Lugosi played second fiddle to Boris Karloff

Hollywood is, of course, no stranger to celebrity feuds. You've got your Bette Davises vs. your Joan Crawfords, your Sarah Jessica Parkers vs. your Kim Cattralls, your Marlon Brandos vs. your Frank Sinatras. Add to that illustrious list Bela Lugosi and the British-born Boris Karloff.

Whether or not the two men actually disliked each other is a matter of lively debate. What's clear, though, is that Lugosi was often on the losing end of Tinsel Town's notoriously flaky attention span. The rivalry all started, according to this piece on Bloody Disgusting, when Lugosi turned down the chance to play Frankenstein's monster in the 1931 film version of Mary Shelley's groundbreaking novel. The role went to Karloff instead, and soon the hollow-cheeked leading man began beating Lugosi out for roles. He even took top billing on films in which Lugosi was the star.

Insult to injury, Karloff was able to move on from his appearances in silly vampire and wolfman and monster flicks to more illustrious roles, whereas Lugosi was stuck in a hall of mirrors of sorts, every new part more ridiculous and broad than the last.

Bela Lugosi had serious financial issues

Bela Lugosi became known as an actor the studios could get on the cheap. Universal Studios paid him only $3,500 for his work on Dracula, and, as this piece in the Standard Examiner illustrates, he was always paid less than his rival, Boris Karloff, for comparable roles. The underpayment was due in part to racism — as a non-native English speaker, Lugosi was often undervalued and taken advantage of — and Lugosi's unwillingness to engage in the age-old art of self-promotion.

When his son, Bela Jr., was born in 1938, Lugosi couldn't afford to pay the hospital bill. According to this look at Lugosi's itinerant LA lifestyle, he had to borrow money from the Motion Picture Relief Fund to cover the medical costs. The bank ultimately foreclosed on the home Lugosi and his then wife, Lillian, were living in at the time.

It was a long way to fall for the star of one of Hollywood's most successful talkies.

Bela Lugosi had war wounds and a drug problem

Bela Lugosi was a working actor when World War I broke out in Europe. His professional status made him exempt from the draft, but he signed up anyway and was made a lieutenant in the 43rd Royal Hungarian Infantry. The division's mission was to launch an attack against Russian troops in Poland. According to The Vintage News, 100,000 Austro-Hungarian soldiers perished in the battle, and Lugosi was promoted to ski patrol. He was sent to fight in the Carpathian Winter War. Wounded twice in the fighting, Lugosi received a medal for his faithful service.

Later, the emotional and physical wounds of the war — not to mention the pressures of Hollywood — caught up with him and he had a very public struggle with drug addiction. In 1955, recently divorced from his fourth wife, he checked himself into the Los Angeles General Hospital Psychopathic Ward, hoping to kick his methadone and morphine habits.

He'd developed the addictions over time, and, as this article in Open Culture shows, he'd grown so sick he could no longer live on his own. Skinny and desperate, he begged a judge to commit him. The judge sent Lugosi to a nearby hospital, where he plotted a comeback that would never materialize.

Bela Lugosi was five times a groom

Despite playing one of the world's most blood-thirsty villains, Lugosi was a lover, not a fighter. In fact, he often told reporters that sex was the most important thing in the universe. So it should come as no surprise, perhaps, that he was married not once, not twice or even three or four times, but five.

His first marriage, to Ilona Smzik, ended in divorce in 1920, reportedly because his lefty politics upset his Smzik's parents. His next bride, Ilona von Montagh, divorced him after three years. For Lugosi, the third time would not prove to be the charm. According to Classic Monsters, his third bride was the wealthy widow, Beatrice Weeks, who grew so enraged over his flirtation with "It Girl" Clara Bow that she dissolved the union after only three months. Incidentally, Lugosi persuaded Bow to pose nude for a portrait artist friend of his, and, as this article on Nitrateville reveals, he happily hung the painting in his many homes, over the possible objections of Mrs. Lugosi Number Four and Five.

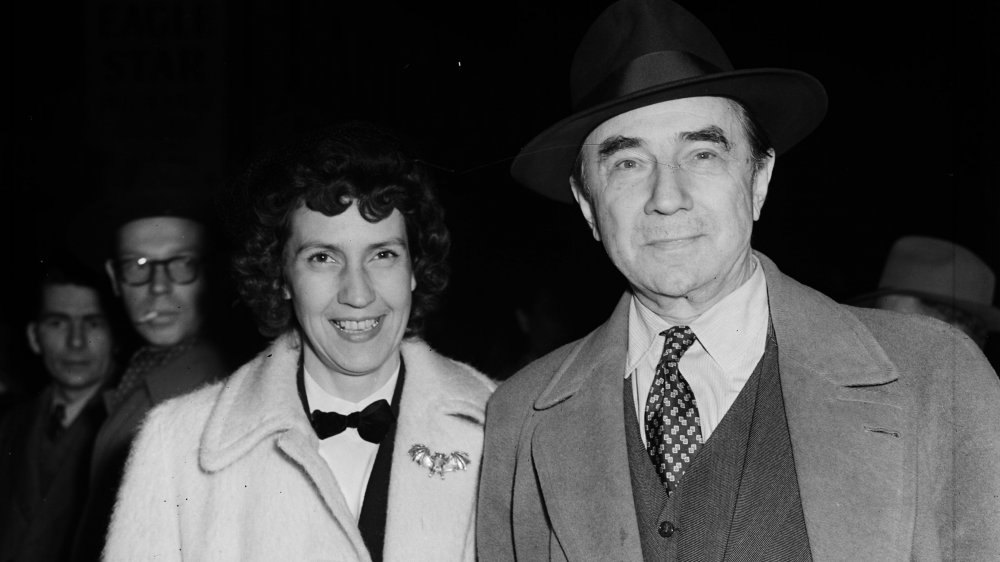

Speaking of, Lugosi married Lillian Arch, his fourth wife, in 1933. Lillian would produce Lugosi's only son, Bella Jr., five years later. Lugosi's jealousy put an end to his union with Arch, who was more than three decades his junior. His fifth and final wife, Hope Lininger, wrote him passionate letters while he tried to kick his addiction to methadone and morphine. He died a year into their marriage of a heart attack.

Enter Ed Wood, Bela Lugosi's second act

Bela Lugosi's film career was all but dead when the B-movie (D-movie?) director Ed Wood single-handedly resurrected it, albeit in an undeniably problematic way. Lugosi's partnership with Wood began in 1953 with the cross-dressing cult classic, Glen or Glenda, written and directed by Wood, a known transvestite. Lugosi plays a character named The Scientist who narrates the hackneyed and often embarrassing but also hilarious exploration of sex and gender identity. Wood plays Glen/Glenda. The film, daring as it is in its willingness to go where no one else would at the time, is considered one of the worst movies ever made.

The same can be said for Plan 9 From Outer Space, which Smithsonian Magazine describes as Wood's "magnum opus of sci-fi schlock." Lugosi died of a heart attack prior to filming. Wood added what footage he had of the star and used and (unconvincing) body double.

It's worthy of its own movie — the love story of two tragically underestimated and maligned men. And, indeed, it was made into a beloved film, Ed Wood, starring Johnny Depp as Wood and Martin Landau as Lugosi. Landau won an Oscar for his turn as the Hungarian heartthrob who'd fallen on hard times. Lugosi was never a contender for such an award. It's enough to make one turn over in one's grave.

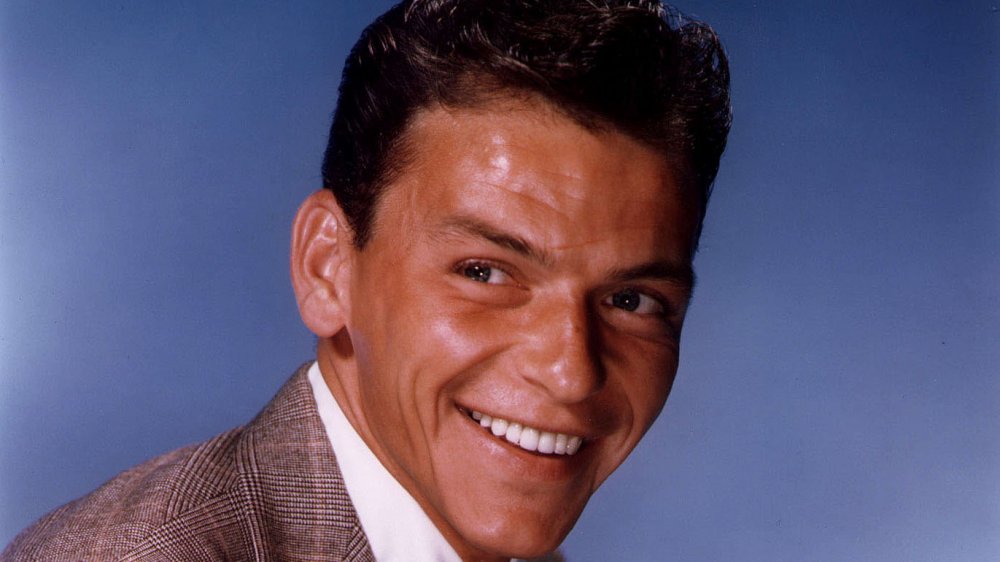

Bela Lugosi was bankrolled by Ol' Blue Eyes

As his career faltered, Lugosi fell victim to drug addiction. In 1955, he checked himself into the psych ward of Los Angeles General Hospital. In some ways, this visit would echo the year his son, Bela Lugosi Jr., was born. At that time, in 1938, the new father was so strapped for cash he had to borrow from a Hollywood relief fund to pay the hospital bills. Nearly 20 years later, Lugosi found himself the beneficiary of an unlikely guardian angel. Without his knowledge, a beloved singer, actor, and fan was helping pay his way through rehab.

Frank Sinatra, fresh off the success of his album, In the Wee Small Hours, was quietly contributing to Lugosi's mental health fund. According to One Room With A View, the two men never met and Lugosi never discovered the reason behind Sinatra's generosity. It was, perhaps, simply the result of admiration and compassion. Regardless, it seems safe to say that, when it came to philanthropy, Sinatra did it his way.

Bela Lugosi was buried in his cape

Lugosi will probably forever be remembered for playing Count Dracula in Tod Browning's 1931 film version of Bram Stoker's spooky novel. His relationship with the movie was fraught: it made him famous and, for a time, quite rich. It made the 6'1" Hungarian hunk irresistible to a series of beautiful women, including the notoriously sexy Clara Bow. It also guaranteed that he would never work as a serious actor again. After Dracula, the bulk of Lugosi's roles were in monster movies of varying degrees of ridiculousness. He spent a great deal of money. He lost even more. He descended into drug use and despair.

According to Lost Magazine, by the time of his death of a heart attack at 73, Lugosi had played the count 1,300 times, both on stage and on screen. It was an inescapable legacy. He was, to moviegoers and followers of 1930s Hollywood, Dracula. Many believed, thanks to the 1994 film Ed Wood, that Lugosi went so far as to sleep in a coffin. Not true, but so is the power of suggestion.

Which makes it somewhat strange that his son, Bela Jr., and fourth wife, Lillian, made the decision to bury Lugosi in his Dracula cape. Strange, but also fitting and bittersweet. Lugosi's final resting place is Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, California. As far as we know, he has never risen from it.

Bela Lugosi lost his rights even in death

Lugosi eventually grew very bitter over the fact that the general public took him for Dracula. He was tortured by the idea that, after his star-turn in the Dracula movie in 1931, no one saw would see him as a complicated human being or a talented, sensitive artist. He was simply, as he put it in this biography, the boogeyman.

Then there was the fact that Universal Studios didn't pay him a living wage for the seven weeks he spent pouring his heart and soul into his portrayal of the bloodsucking count from Transylvania. Since the studio executives refused to give him his due in life, Lugosi's family — namely his son, Bela Lugosi Jr., and his fourth wife, Lillian — were determined that Universal Studio would not be able to profit off his likeness in death. In 1966, Bela Jr. and Lillian sued Universal Studios for using Lugosi's personality rights without his heirs' permission.

The case took 11 years to litigate and went all the way to the California Supreme Court, where, according to FindLaw, the justices ruled that dead people do not have any right to their own likeness and that their heirs are likewise without recourse. In 1986, the court's decision was, in effect, overturned with the ruling in the California Celebrity Rights Act stipulating that children and spouses of celebrities have jurisdiction over the use of their loved one's likeness up to 70 years after the celebrity's death.