The Hidden Meaning Of Charlie Daniels' 'The Devil Went Down To Georgia'

"For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?" Gospel of Mark, 8:36 (King James). Or, for that matter, a golden fiddle?

Making a deal with the devil for some kind of personal gain or profit isn't a new literary device. The basic construct: an individual, already talented and gifted, wants — more. Much more. Now. Poof! A mysterious stranger appears. Sign away your soul in the future in exchange for what you think you want and need now. The German story of Faust is one version — it goes back to at least the 16th Century. Sometimes Faust beats the rap, and sometimes he doesn't and is carried off to hell at the end of his life. Either way, the story's got legs. Stephen Vincent Benét reworked it a bit in 1936 for The Devil and Daniel Webster, in which a New Hampshire farmer trades his soul to the devil (Mr. Scratch) in return for a few years of prosperity.

When time comes to collect the debt, the farmer asks Webster to defend him. The Devil agrees. And Webster — well, read it for yourself. (It's fun.)

Benét's classic story draws upon an earlier, similarly-themed work of his — a poem titled "The Mountain Whippoorwill", published in 1925, and subtitled "How Hill-Billy Jim Won the Great Fiddlers' Prize," according to the Poetry Foundation. The poem features lines like "He could fiddle down a possum from a mile-high tree", and "Hell's broke loose in Georgia." Sound familiar?

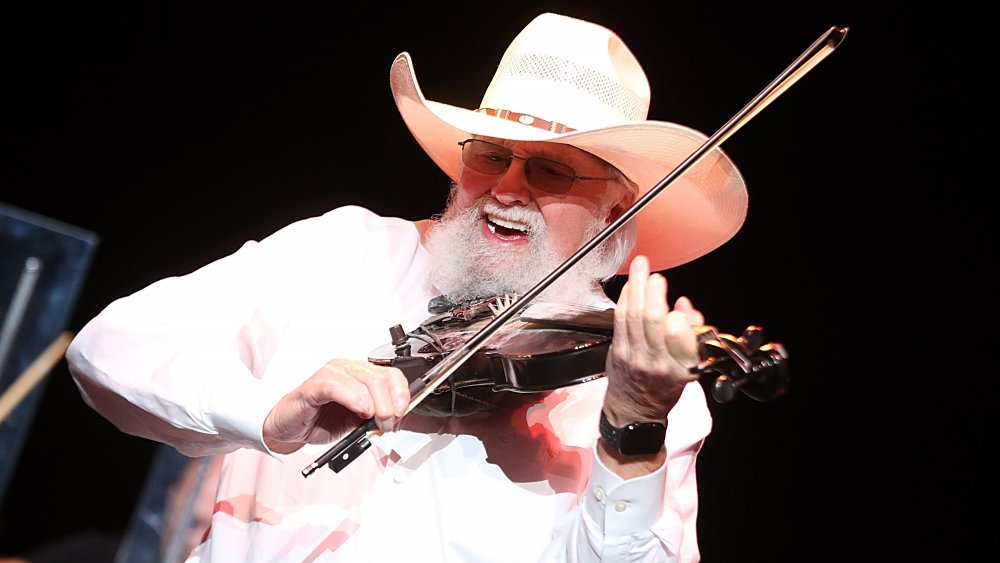

Daniels was a multi-instrumentalist

All of that seems to have been in the back of Charlie Daniels's mind when he was working on his album Million Mile Reflections. He told Songfacts that the band was about done when they realized they didn't have a fiddle selection among the tracks. They took a break from the studio to remedy the situation.

"I just had this idea: 'The Devil went down to Georgia,'" Daniels said. "The idea may have come from an old poem that Stephen Vincent Benét wrote many, many years ago. He didn't use that line, but I just started, and the band started playing, and first thing you know we had it down."

The Morning Call reports that Daniels also read The Devil and Daniel Webster in his youth, after it was assigned by his literary mentor, Miss Ethel Odom, noting that "he continued to "honor her legacy by promoting literacy and consuming books."

As Rolling Stone quotes his 2017 autobiography, Daniels was more vague about his spin on the archetypal tale: "I don't know where the phrase 'The Devil Went Down to Georgia' came from or why it entered my mind that day in the rehearsal studio. I don't even know where the song idea came from... But when it started coming, it came in a gush." Whatever the inspiration, "The Devil Went Down to Georgia" gave him his only #1 hit, says The Cheatsheet.

The whole band got songwriting credit for "The Devil Went Down to Georgia"

In the song, the Devil approaches Johnny, a fiddler, and proposes a fiddle-off: If Johnny wins, he gets the Devil's golden fiddle. (Perhaps more decorative than functional. But we digress.) If Johnny loses, the Devil gets Johnny's soul. Deal? Deal.

The track's writing credit goes to everyone in the band, not just Daniels, though it was Charlie who played both fiddle tracks — Johnny and the Devil. The 1979 single put Daniels and his band firmly in the spotlight ever after, a crossover hit on both Country and pop charts that cemented his place solidly in the Southern Rock movement. It earned the Charlie Daniels Band a Grammy award, says the Wall Street Journal, and helped propel sales of the soundtrack for the movie Urban Cowboy.

There you have it: The Devil Went Down to Georgia is contemporary Southern take on a classic story, and in many ways, life imitated art. Like Johnny, Daniels managed to honor his roots and gain the world without selling his soul, going on to be inducted into the Grand Ol' Opry in 2008 and the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2016. He released his last album, Beau Weevils — Songs in the Key of E, in 2018, before passing away July 6, 2020.