Confucius May Never Have Actually Existed. Here's Why

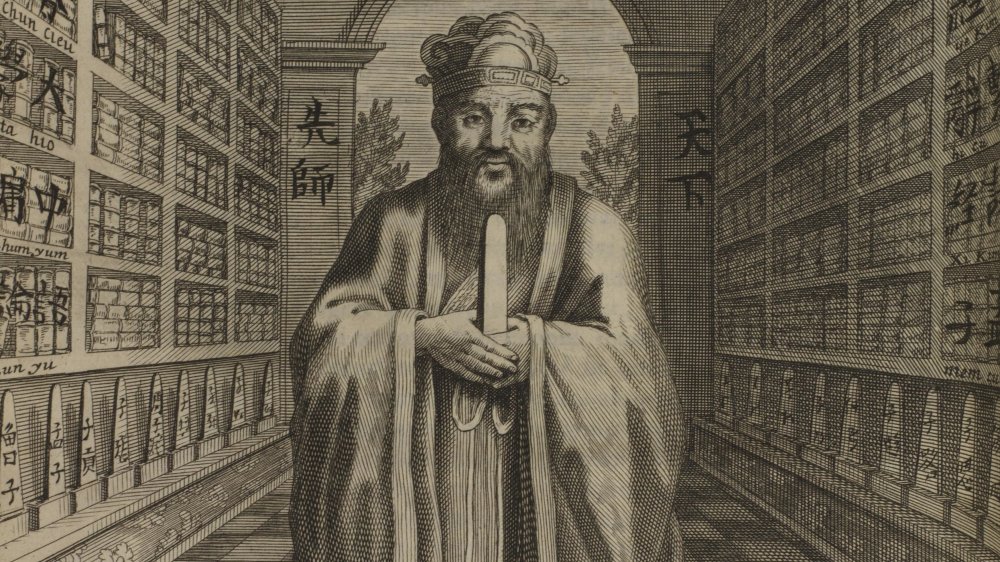

As every teacher has told every class, "Write it down or you'll forget." (Was anybody listening? Ever?) Somebody call Indiana Jones, because we need some historical artifacts stat. Particularly something related to the life and times of Confucius (sometimes expressed as Kongzi, says the Ancient History Encyclopedia; Kong Qiu, says Asia Society; K'ung Fu-tzu, per Biography). There's rough agreement about the revered Chinese philosopher's dates — born around 551 BCE, died around 479 BCE. It's the in-between part that's a little problematic. Globally, he was a contemporary of a number of writers and philosophers who've continued to have an enormous impact on our world: Plato; the Buddha; Zoroaster; the Hebrew prophets. Like many Greek philosophers, the works attributed to Confucius (a name cobbled together by Europeans) come not from the man himself, but from reports written by his followers (who apparently did listen and did write it down).

Much of those works come to us as collections of sayings and observations, which he, in turn, attributes to the wisdom of the ancients — the older days, when people were wiser, more virtuous: "Don't innovate, stay true to the old ways, honor your parents, remember your duties and responsibilities," as Asia Society summarizes. To add to the Confucian confusion, the earliest biographical account we have came some 400 years after his death. Our knowledge of who the real Confucius was comes through a worldwide, 2500 year-old game of "telephone". Still, his influence is undeniable.

Most of what he wrote comes not from him, but from his disciples

Confucian thought emphasized the concept of harmony, says the Confucian Weekly Bulletin, something adapted by the Chinese Communists when they came to power. Before that, "Confucianism," or the "School of Confucius," was adopted by Emperor Han Wudi a couple of hundred years after the philosopher's death. As Encyclopedia Britannica tells us, the philosophy of Confucius wasn't a matter of some kind of divine intervention; he came to his wisdom through a process of "self-cultivation." A person could become a sage, a person of wisdom and understanding, by working at it — no matter how they started life: "human beings are teachable, improvable, and perfectible." Anyone — rich or poor — could become one of his students. Leaders should conduct themselves with compassion, good example, and self-discipline.

He's credited with four books, perhaps the most important of which is the Analects, which details his philosophical ideas. He was strongly concerned with living a moral life, and his thought is often distilled into a handful of principles, per Ancient History Encyclopedia: "benevolence (jen), righteousness (i), observance of rites (li) and moral wisdom (te)." A fifth principle — faith — was added later, "which neatly corresponded to the five elements (in Chinese thought) of earth, wood, fire, metal and water."

How much of his wisdom actually came from him? How much of Confucius was myth, rather than man? We might never know. Maybe that's one more reason why "faith" was added.