The Untold Truth Behind The Tales Of Ripley's Believe It Or Not

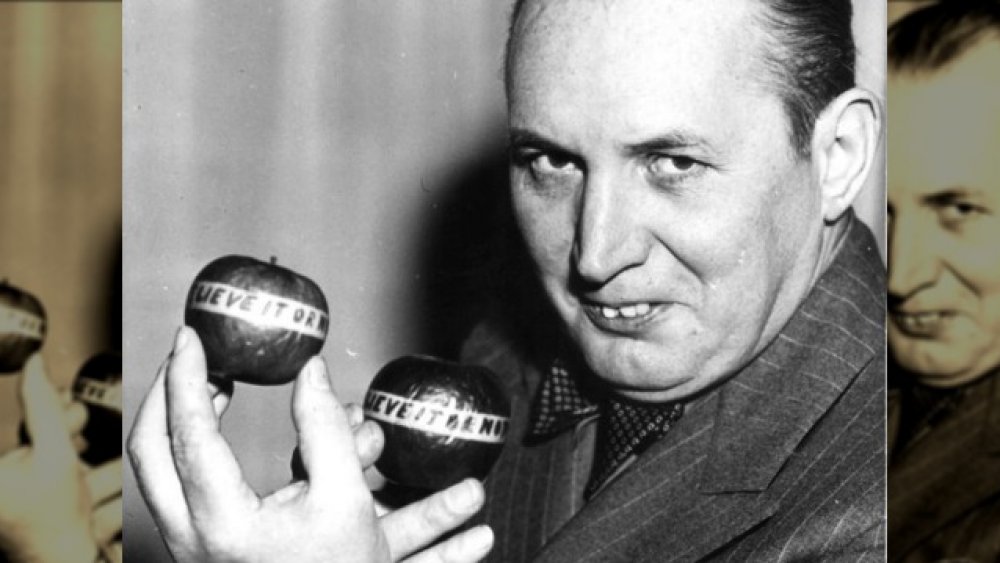

Back before the internet, before memes, and even before email chains claiming things like, "KFC uses mutant chickens, for real, how else do they get all those chicken parts?" there was another source for some of the most outrageous stories in the world: Robert Ripley.

While most of us might remember the version of the television show with Jack Palance, Dean Cain, or Bruce Campbell, Ripley's oddities collections go back much farther, to when, after breaking his arm and ruining his pitching career with the New York Giants, (believe it, says PBS), he became a cartoonist. His "Believe It or Not!" cartoon debuted in 1918 (via Britannica), and that turned into collecting and the sponsorship of exhibits he called "Odditoriums," where people could come and look at proof of his tales. He died in 1949, but his work continued.

People have been fascinated by the outrageous tales of Ripley's for decades... but should you believe them? Or not? Let's look at some of the most famous.

The mummified corpse that attends board meetings

The claim: The pilot episode of Ripley's Believe It or Not! started big, and included the tale of Jeremy Bentham, a philosopher firmly on the side of the eccentric. In his will, he made it clear what he wanted to happen to his body: it was to be installed in his beloved University College London. To this day, his preserved remains are rolled into council meetings, and he's given the deciding vote in case of a tie. (By default, he votes "yes.")

Believe It, or Not?: Partial truth. Jeremy Bentham's preserved skeleton does sit in the Student Centre of University College London. It's dressed in his clothes, and it's sporting a wax head. Bentham had originally wanted his actual head to be sitting on top of the actual shoulders of what's called an auto-icon, but when his head was being prepared for display, the process went terribly wrong and a wax head was commissioned. The real head sat at his feet for a long time, but more recently, it's been put on display, stolen by UCL's rivals, King's College, and then returned to a secure location that UCL curator of collections, Subhadra Das, says (via the CBC) will help preserve the head from deterioration.

What about the claims that Bentham's remains preside over council meetings and get a deciding vote? UCL says no, he's not moved, and no, he doesn't get a vote.

Man finds message in a bottle, inherits millions

The claim: In an episode that originally aired on October 3, 1982, Ripley's Believe It or Not! did a recreation of a chance discovery. The story claimed that a San Francisco man walking along the beach picked up a bottle with a note inside, that happened to be the will of an English heiress who had thrown the bottle into the Thames about 10 years prior. He inherited millions.

Believe It, or Not?: Partial truth. According to the Museum of Hoaxes, the story's been told repeatedly since the find date of March 16, 1949. And there are some true elements. The heiress in question was Daisy Alexander, and she was the daughter of Isaac Singer of the sewing machine fame. After the death of her husband in 1931, the one-time socialite retreated into a life of seclusion and ultimately passed away herself in 1939. And she did leave behind a massive estate, one for which the will mysteriously disappeared.

There was a massive scramble to find anything that dictated how her estate was to be distributed, and the search got so desperate that spiritualists were consulted. Then, in 1949, Jack Wurm's note-in-a-bottle story hit newspapers. Wurm did get in touch with Alexander's estate, but bottom line? The will couldn't be authenticated, the signature wasn't witnessed, and it was written off as a hoax. The estate went to Alexander's niece and nephew.

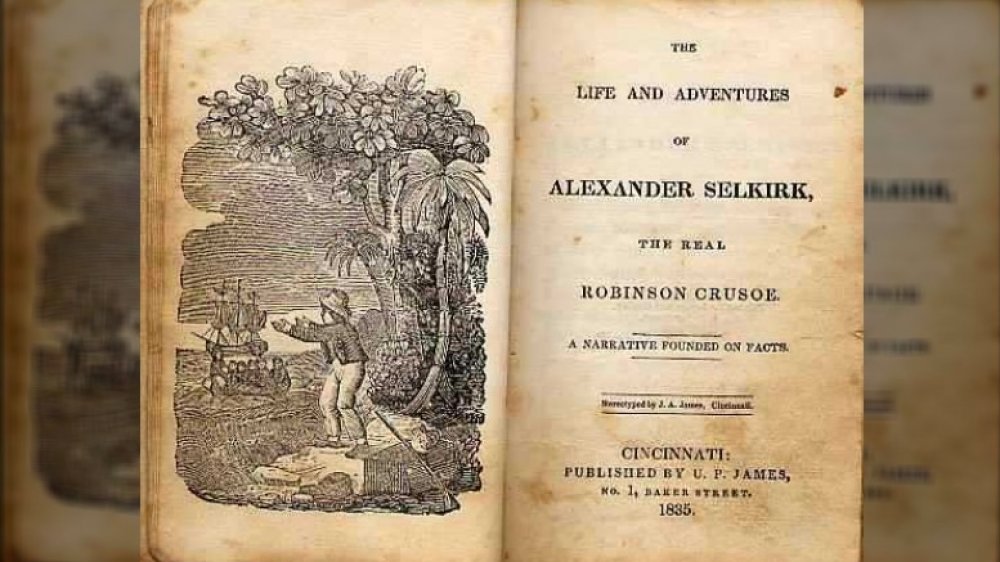

The real Robinson Crusoe?

The claim: This one comes from an episode that originally aired on October 24, 1982. In a nutshell, it's the claim that the story of Robinson Crusoe was real — and his name was actually Alexander Selkirk.

Believe It, or Not?: Partially true. According to National Geographic, Robinson Crusoe author Daniel Defoe was heavily influenced by what they describe as a whole genre of literature that was coming out at the same time Defoe was writing: "real-life buccaneer survival stories." Experts say that while Selkirk's story was out there, it was only well after Defoe's death that the claim surfaced that the entire thing had been based on the Scottish privateer. And experts say that it's incorrect: while there were real-life influences, Selkirk wasn't a big one.

And that's starting with the fact that Selkirk wasn't actually shipwrecked: after an argument with the captain about whether or not their ship was seaworthy (he was right — it wasn't), he opted to be left behind on an island. Other differences? Selkirk was a pirate, was completely alone on his island, and spent his time there pretty much just hanging out.

Other stories of shipwrecked individuals contain more elements of the Crusoe story, like William Dampier's. He was stranded on an island a few decades earlier, and he befriended a man very much like Crusoe's Friday.

It's scientifically impossible for a bumblebee to fly

The claim: In early 1983, Ripley's Believe It or Not! repeated a claim most of us have heard repeatedly: it's scientifically impossible for a bumblebee to fly.

Believe It, or Not?: False. First, because obviously, bumblebees do fly, and it turns out, says LiveScience, that they're not defying any laws of physics after all.

The idea that bumblebees shouldn't be able to fly comes from being based on one particular kind of flight: an airplane's. If you assume that a bee's wings work the same as a plane's, then no, they shouldn't be able to fly. Fortunately for bumblebees, they absolutely don't work the same as airplanes.

In 2005, high-speed photography confirmed what scientists suspected: bumblebees (and other insects) don't fly in an airplane fashion, or by flapping their wings the same way birds do. Instead, they actually move their wings back and forth, front to back. It's a motion more like helicopter blades than a birds' wings, and the angle of their wings serves to keep the bees aloft by essentially creating little, miniature hurricanes that change the air pressure in the area around them. Pretty neat, right?

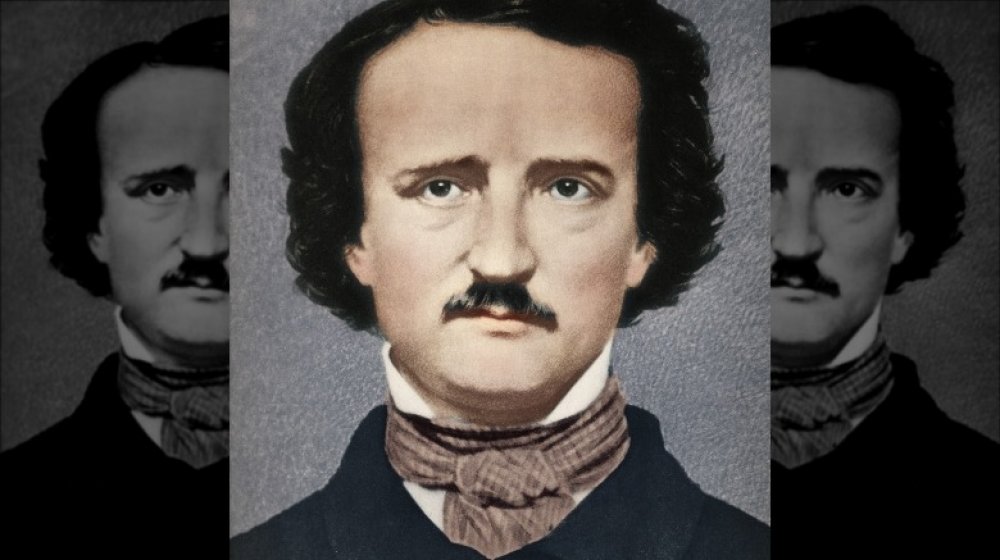

Edgar Allan Poe's only completed novel turned into a true story

The claim: Edgar Allan Poe is known as a master of the macabre, and in a 1983 episode, Ripley's Believe It or Not! claimed that his only completed novel came true in an eerie way, decades after it was published — right down to the cannibalism.

Believe It, or Not?: Completely true (via the BBC). The book is The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, and it's basically the story of a boy who stows away on a whaling ship. There's a mutiny, a storm, and a shipwreck, and Pym finds himself afloat on the ship's remains. With him are his friend Augustus and two other sailors — Dirk Peters and Richard Parker. After days on the ocean, after being only able to catch and eat a single turtle, they decide they're going to have to kill and eat one person. They draw lots; Parker draws the short straw and becomes the main course of the "fearful repast."

The book was published in 1838, and now, let's fast-forward to 1884. That's when a ship called the Mignonette left England for Australia, was caught in a storm, and stranded four survivors on the wreckage (via Mental Floss). They managed to kill and eat a single turtle, but when one of them started drinking seawater and subsequently started getting sick, they decided not to draw straws after all. Instead, they stabbed him in the throat, drank his blood, and ate him.

His name? Richard Parker. The surviving men were rescued a few days later.

The murderer who wrote the Oxford English Dictionary

The claim: The Oxford English Dictionary is a go-to reference, and according to a 1983 episode of Ripley's Believe It or Not!, much of it was compiled by a man who was serving a life sentence for murder... at the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum.

Believe It, or Not?: Completely true. His name was William Chester Minor, and the OED lists him as one of their major early contributors.

According to the BBC, Minor was born in 1834. By 1868 he was committed for the first time, and after his release, he moved to London. Just three years later, he shot and killed George Merritt, believing the man was breaking into his room. (He wasn't.) Found not guilty on grounds of insanity, he ended up in Broadmoor.

He was given two rooms, and used his Army pension to buy so many books that one became a library. By 1880, he'd gotten wind of a new literary project — the OED — and spent years collecting quotations that were used to illustrate the different uses of various words. Dr. James Murray, the editor of the OED, didn't meet Minor until 1891, and had only learned he was an asylum patient in the late 1880s. It's not known just how many contributions he made, but Murray would write (via Mental Floss) that during just two of the 20 years he worked on the project, he submitted 12,000 quotes.

The Touch of Death

The claim: This one comes to us from a 2000 episode of Ripley's Believe It or Not!, and it's the idea of dim mak — a martial arts move that seems to deliver a non-lethal blow, which actually results in instant or delayed death.

Believe It, or Not?: Somewhat true. According to Gizmodo, dim mak is mentioned in historical martial arts texts, and the translation of the term says it's deadly pressure applied to an artery.

Death from a blow like that can happen, because it disrupts the heart's rhythm and the electrical pulse that keeps the body's systems working in sync. The medical term for it is commotio cordis, and it happens more than you might expect. There are more than 125 confirmed cases of it, including several hockey players who died after being hit by speeding pucks.

In other cases, a single strike might end in death because it decreases blood flow to the brain — something like the Vulcan nerve pinch. But this doesn't get a "completely true" rating for a few reasons. Any actual moves that can do this are a mystery. Secondly, there's no medical proof of a strike that can at first seem completely harmless, then result in a delayed death... maybe. The Art of Martial Arts suggests that a dim mak shot might impact blood flow and then organ function, and if organs start to fail, you're going to die.

The sculptor who worked in the medium of corpses

The claim: It was an episode of Ripley's Believe It or Not! that first aired in March 2000 which spotlighted an art collection so grisly, it was completely understandable if people didn't want to believe it. It belonged to Honore Fragonard, and it was made completely of flayed, preserved, and posed corpses.

Believe It, or Not?: Completely true. They're on display at the Musee Fragonard today, or rather, the ones that are left. Honore Fragonard, says Atlas Obscura, was appointed as a professor at a veterinary school in Lyon, France, by none other than Louis XV himself. He worked there for around six years, and during those years, he also started creating what he called his "écorchés," or his "flayed figures." And they were exactly that, cadavers of humans and animals that he flayed and prepared in some super weird ways. Just take one of the surviving examples: it's a skinless man on an equally skinless horse, posed in a way that paid homage to his inspiration — Albrecht Durer and his horsemen of the apocalypse.

Not surprisingly, Fragonard and his flayed figures creeped people the heck out. He was ultimately fired and declared insane, says Hyperallergic, but he continued making more and more of the figures that started out as teaching tools and ended up just disturbing pieces of art. No one's sure how he did it, but whatever he did, well, beauty is in the eye of the beholder?

The boy raised by monkeys

The claim: Tales of feral children are a dime a dozen, but according to a 2000 episode of Ripley's Believe It or Not!, at least one was very different. In 1991, the tale goes, a woman in Uganda came across a boy of about 5-years-old. He'd fled into the jungle, where he'd been found and raised by a group of monkeys.

Believe It, or Not?: Completely true. The boy was John Ssebunya, and his tale — via the Molly and Paul Child Care Foundation and The Guardian — starts out with some unclear details. He was born near Bombo, Uganda, and when he was somewhere between 2- and 3-years-old, he was witness to a terrible murder: his father killed his mother.

He fled into the forest, where curious vervet monkeys (like the one pictured) approached him. It wasn't long before they were feeding him, eventually accepting him into their family unit. And he lived that way for years, until he was discovered and brought back into civilization and taken to an orphanage. Over the following years, he was taught the basics — like how to speak, and how to walk upright. By 1999, he had been adopted by Paul and Molly Wasswa, become an invaluable member of the Africa Children's Choir, and had already decided that when he grew up, he wanted to work with animals... just not monkeys.

Verdun: the town still littered with World War I explosives

The claim: Sometimes it's not the weirdness but the scale that makes a story seem absolutely impossible, and that's the case with one tale told in a September 2000 episode of Ripley's Believe It or Not!. This story featured the French city of Verdun, which was said to still be covered with unexploded ordinances from World War I that residents frequently found, and were occasionally killed by.

Believe It, or Not?: Completely true. In 2018, Reuters reported on that same area in France as part of their spotlight on the 100-year anniversary of the end of World War I. Bomb disposal experts, they said, were still working to dig up munitions that, since the end of the war, had sunk underground. They were nowhere near finished, either, and experts estimated that there were still so many shells left that it would be at least another 100 years before the area was cleaned up, and once again safe.

Unthinkable? There's more to it. They're not just finding a few shells a day. In one day of dredging the River Meuse, they pulled out five tons of unexploded shells, and while that was an unusually productive day, they estimate that in each year, around 45 to 50 tons of shells are removed.

The dizzying religious rituals of the Whirling Dervishes

The claim: On May 5, 1983, the spotlight was on the Whirling Dervishes and their dizzying ritual. The Dervishes do exactly that: they spin and spin and spin, while entering a trancelike state that keeps them from even getting dizzy.

Believe It, or Not?: Completely true. Today, says The Washington Post, visitors to Turkey can go and see performances of the Whirling Dervishes, but those public performances are much more touristy than the real thing.

And that real thing started way back in the 13th century, when the Sufi Muslim poet Jalaluddin Rumi started using dance as a way to meditate. By the 15th century, the tradition had spread so far and through so many different sects that the Mevlevi order established rules to keep the tradition firmly grounded.

So, clad in robes and cloaks that represent the ego and the worldly life, the Dervishes (which means "doorway") perform a complex series of spins and movements — according to the Sleep and Health Journal, they average between 20 and 30 spins per minute. And no, they don't experience any dizziness or vertigo. Research published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience found that after hundreds and hundreds of days of training in meditation and whirling, there were noticeable differences in the structure of a Whirling Dervishes' brain that seemed to show that yes, they were training themselves to be able to overcome dizziness.

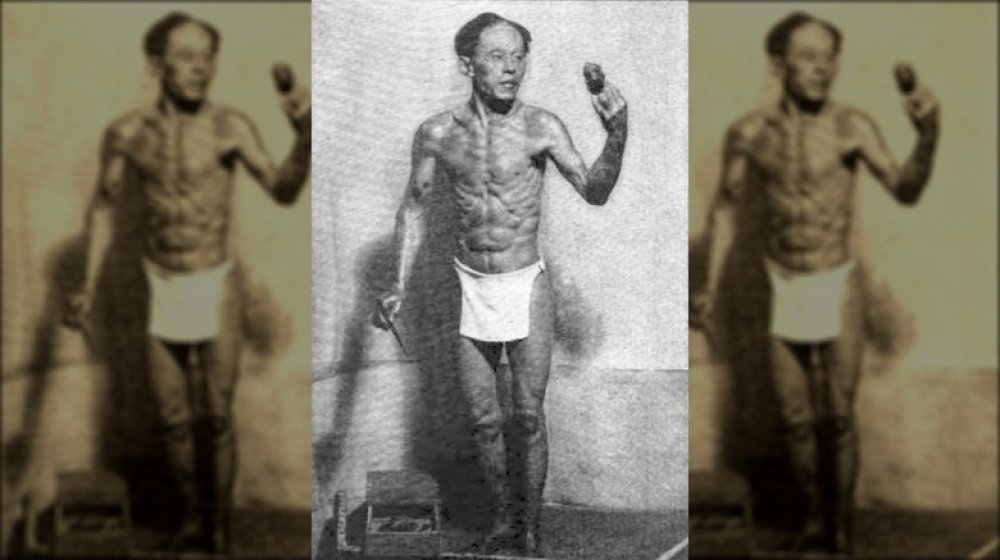

Man... or statue?

The claim: According to a 1984 episode of Ripley's Believe It or Not!, a man named Hananuma Masakichi had gone so far in making a statue of himself that it was completely indistinguishable from the real thing.

Believe It, or Not?: Partially true. According to Atlas Obscura, the statue in question resided at Ripley's Odditorium in Amsterdam for a long time, and it was one of Ripley's favorite exhibits. It is incredibly — almost terrifyingly — lifelike, and the story goes that it was made by a man who was diagnosed with tuberculosis, and wanted to leave one last gift for the woman he loved.

Masakichi was already known as a gifted craftsman, and he created iki-ningyo, or "living dolls." Think of them as sort of like 19th century Madame Tussaud's figures. But for this, the story says, he went the extra mile, even using his own hair, teeth, and fingernails (among other things) and inserting them into the statue to get its eerie appearance. And here's where the problem comes in.

Yes, the figure is incredibly lifelike, but given that there were no self-portrait traditions in Japan during that time (and no surviving portraits of Masakichi), it's unclear if it's even him. The hair is real (but could have been sourced from any number of places), and there's been no verification of the tuberculosis love story, so that part is still up for debate. (And yes, that's the statue in the photo.)