The Bizarre History Of Ska Music

Whether you're an aficionado of 2 tone who knew what a rude boy was before Rihanna sung about them, the type to skip through the trumpety bits of classic punk records, or have no idea what any of those things mean at all, chances are good you've heard ska music before in some capacity.

Ska is often compared to, and confused with, reggae, but there are notable differences. The ska style's signature brass section and quick, jumpy guitar rhythms dominated much of the American mainstream rock sound of the mid-to-late '90s and hasn't totally gone away since. The same is true of ska's distinct mod fashion aesthetic and its truly indescribable signature dance move (or mosh pit move, if you were the punk mentioned above): skanking.

But the genre described in a popular meme as "what plays in a 13-year-old's head when he gets extra mozzarella sticks" has a story even more fascinating than that description suggests. This is the bizarre history of ska music.

Ska began with slavery

While most American iterations of ska and the more commonly-heard ska-punk have tended to be dominated by white musicians and bear a permanent association with the '90s, the genre was actually invented in Jamaica by Black artists in the mid-1960s. But to understand the origins of the style, you have to go back even further, to when Africans were first enslaved and taken to the island as laborers after the occupying Spanish had killed most of the native Taino and Arawak people.

England took over Jamaica from Spain in 1655 and took control of the island's resources. During the long slavery era, enslaved Africans in Jamaica were allowed to keep some cultural and musical traditions — particularly drumming, according to Paul Kauppila at San Jose State University, because plantation owners believed it would help motivate their captives to work harder. But slaves in nearby New Orleans, Louisiana were allowed to play music publicly in places like Congo Square. Not only was this part of jazz's origin story as well, but it was the beginning of a long affinity between the New Orleans and Jamaican music styles that developed in back-and-forth tandem over time.

With freedom came an African cultural revival

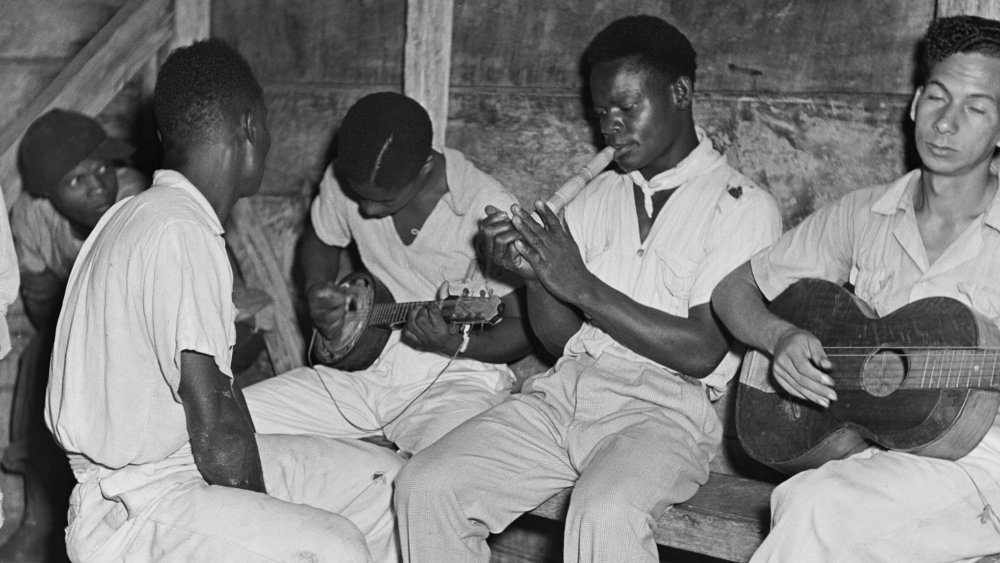

When slavery was finally outlawed in 1834, it set off a huge revival of African cultural traditions in Jamaica. Music was, of course, a major part of that. Some features of traditional African folk music from different regions, like clapping, stomping, percussive breathing and improvised melody, began to experience a resurgence and make their way into contemporary Jamaican music.

After the turn of the century, the island began to urbanize quickly as more people were moving out of rural areas and into the cities, where the bustle of daily life started to influence popular music. San Jose State University describes how musicians would wander the streets of Kingston playing the popular mento style of music — similar to the calypso, and a blend of the revived African folk styles and the European quadrille music so many enslaved musicians had been forced to learn — on portable instruments, like the guitar, banjo, bongos, or the kalimba, an African thumb piano.

Vinyl was so popular it could be used as currency

By the 1940s, music had become more accessible than ever, thanks to modern inventions like radio and records. But even though slavery had ended long before and independence from Britain was just on the horizon, there was still severe inequality in Jamaica that affected who heard what music. According to Atlas Obscura, American music became a kind of luxury signal, since those records often wouldn't arrive in Jamaica until years after their initial release. Once the records did finally arrive, the working class in Kingston often couldn't afford to buy the pricey imports, to say nothing of record players or radios. Jamaicans who went into the U.S. to perform seasonal farm labor would come back with the highly sought-after big band, R&B, and jazz records.

Demand for the music was so high that American soldiers, stationed in Jamaica during World War II, would trade their own vinyl for marijuana. Even more incredibly, according to San Jose State University, they frequently paid sex-workers with their records instead of money. It's difficult to imagine in our modern age, where you can buy new music from an artist within seconds of it being released and even the concept of paying money for music is starting to seem antiquated. But what we might think of as an outrageous inconvenience today actually helped foster the development of ska music.

Radio inspired ska's sound in more than one way

The excitement for big band began to wear off as the island continued to urbanize, and Jamaicans started to get tired of American pop. According to the Heritage of Ska Festival, they turned their radio dials to New Orleans and Miami stations, where they could hear the rhythm & blues of artists like Amos Milburn, Fats Domino, Jelly Roll Morton, Champion Jack Dupree, and others who, like them, were descended from kidnapped and enslaved people who carried and evolved their musical traditions down through the generations into something entirely new.

The radio did more than just introduce Jamaican audiences to the new American artists whose sounds helped to seed ska. In fact, one theory about how the choppiness of the guitars and the use of delay that would soon become features of ska developed is that musicians were mimicking the delay and breaks the in the radio waves from far-off stations, although it seems more likely they were inspired by the actual music folks were hearing: the fast, bouncy boogie-woogie and R&B piano stylings coming out of New Orleans.

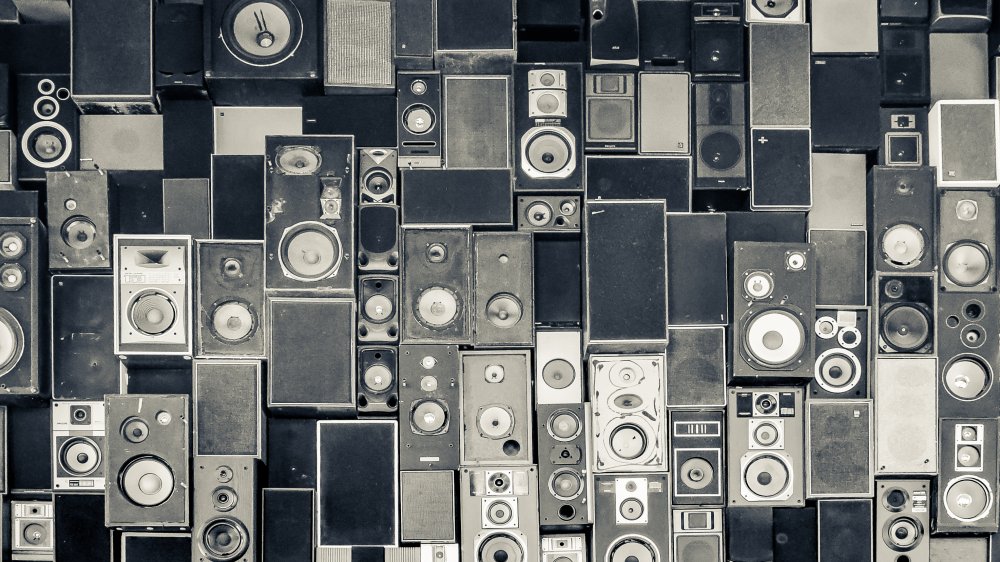

The sound system changed everything

The cost of a home record system was equal to about a year's pay for most of the working class, as San Jose State University notes, and few could afford these new popular records from the U.S. (and even if they could, the records took years to arrive after their initial release stateside). So as Jamaica's city-dwelling music-lovers continued to seek out the latest music from the other side of the Gulf, they came up with a bold new way of bringing it directly to the people. This is how what came to be known as "sound systems" were born.

Following in the footsteps of the mento street performers, sound systems, or mobile dance parties, were organized around flatbed trucks carrying speakers, amps, and turntables. They'd set up in the street, charge cheap admission prices, and sell popular local foods like curry goat, roast fish, cornbread, and of course, Red Stripe beer. In addition to providing the community with new, exciting music, and a place to gather, dance, and unwind, sound systems also created some major rivalries between operators.

The latest records became the source of serious competition

The sound system was such an important part of ska music that it continued to be memorialized in songs decades later, notably in '80s Bay Area ska punk band Operation Ivy's "Sound System." But because these dance parties were becoming lucrative for the operators, it also inspired fierce competition over who could get the best and most exclusive records.

As San Jose State University explains, the deejays and curators responsible for spinning the newest, hottest sounds (especially those elusive American R&B records) began to feel the pressure to outdo each other. They'd cover the labels on their records or paint over with their own so no one else could find out what the DJs were playing and bring it to competing sound systems. The "selecters" who helped throw the popular street parties went out of their way to befriend American record execs so they could get their hands on the very latest popular music before anybody else. That element of cool exclusivity only added to this exciting new way of connecting through music.

Nobody knows who really invented ska

Another cultural revival exploded across the island after Jamaica finally won independence from Great Britain in 1962, and that sense of optimism and possibility was palpable in the cheery-yet-politically-aware ska sound. As sound systems took off and the demand for more new music just kept growing, a uniquely Jamaican take on rhythm and blues developed, with quick, jumpy rhythms from the snappy guitars and piano making it perfect for dancing. There's still disagreement over who truly invented ska, but the truth is that like any other genre, no one person can really claim to have started it.

It is generally agreed, however, that guitarist Ernie Ranglin invented the muted "ska chop," according to Encyclopedia Britannica. Cecil Bustamente Campbell, AKA Prince Buster, was known as the father of ska, and his song "Shaking Up Orange Street" paid homage to the part of Kingston that had become a musical mecca by the early '60s and in whose studios the ska sound was crafted, as explained in Atlas Obscura. Recording studios, record stores, and a general feeling of community permeated the street, connecting the community through the shared joy of music and continued survival among colonialism. Even the name "ska" is difficult to trace. Some early ska musicians said the name came from onomatopoeia describing the upbeat, chopped sound the electric guitars made, like "skat-skat-skat," noted by Heritage of Ska.

Ska's greatest trombonist was also its most tragic figure

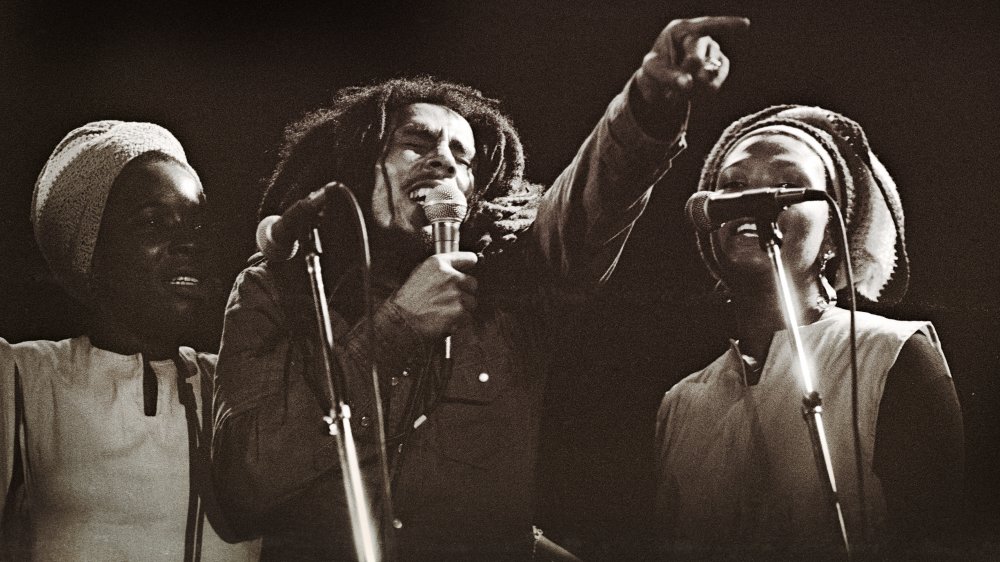

In the beginning of ska, it was more common for bands and singers to perform the indigenous, urban pop music together, but operate separately. According to Klive Walker in his book Dubwise: Reasoning from the Reggae Underground, the music created by working class musicians in the studios of Orange Street became so popular that it transcended class divides and became popular with established writers and artists. In 1963, the instrumental group The Skatalites formed, encapsulating the country's love affair with ska. They performed with the best and most popular singers in Jamaica, including a young Bob Marley. Their trombonist Don Drummond still holds a solemn, important place in the collective memory of the genre.

Drummond joined the group in 1964, quickly became revered around the world for his supreme skill, and is still regarded as a musical genius today. But only a year later, he would be convicted for the murder of his significant other, the beloved singer and dancer Anita "Marguerita" Mahfood. Drummond was declared insane and institutionalized, and he died four years later. Conspiracy theories soon grew around Drummond's death, with some believing the American government had him murdered and others claiming it was gangsters committing a revenge killing over Mahfood.

The British fell in love with ska right away

Even though Jamaica had just freed itself from British rule, the sounds of ska had already begun to travel across the Atlantic right from its late '50s sound system beginnings. There, it caught on quickly and became known as Bluebeat. The large "West Indian" population in Britain was a ready-made audience for the newly created music sensation from the island. Back in Jamaica, ska was already beginning to give way to rocksteady, which would then lead to reggae by the early '70s. But the British mods, skinheads (nothing like what we in the U.S. recognize as skinheads), and other hip, well-dressed kids took a shine to the genre quickly.

As explained by Heritage of Ska, a white Jamaican descended from aristocrats, Chris Blackwell, is credited with much of ska's British popularity. He started a record label and small-scale distribution network focused on "ethnic" music and, realizing how much appeal Jamaica's answer to the blues had, brought the sounds of a young Bob Marley, the Skatalites, Jimmy Cliff, Millie Small, and more to the U.K. Millie Small would even have a huge U.S. hit with "My Boy Lollipop."

Ska gave way to reggae before making a huge comeback

The ska style known as 2 tone developed in the late 1970s and early '80s in England. According to SF Gate, while reggae was exploding in Jamaica, the popularity of new wave in the U.K. made nostalgia for '60s ska fashionable, and British bands picked it up (pun intended). So while Jamaicans were exploring the possibilities of reggae and Bob Marley was cemented as a global phenomenon, passing away in 1981 but leaving an unending legacy, the Brits were more interested in experimenting with the earlier stuff. This second wave of ska produced 2 tone bands we still know and love today, like the Specials, English Beat, and Madness.

Despite the diverse working class with whom the genre originated, inevitably as it gained popularity in the U.K. the most prominent faces of 2 tone were white. While bands like the Specials and English Beat were visibly interracial, this would influence the American take on ska in the '80s. Other popular and new British styles at the time included punk and music-hall (like the more modern British equivalent to vaudeville), both of which would borrow from and influence ska, especially on the other side of the Atlantic. It's from this mixture of politically-charged, highly danceable music styles that 2 tone paved the way for ska-punk.

Punk became intertwined with ska as it took off in the U.S. and U.K.

Punk influences traded back and forth from the U.S. to the U.K. just like R&B had between the U.S. and Jamaica. The political message of early ska resonated with like-minded American and English punks during their years living under the conservatism of Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, and ska-punk developed from there. One of the most notable bands early on was the incredibly short-lived but influential Operation Ivy from California's Bay Area. Op Ivy's potent anti-racist message reflected much of the early American ska-punk attitude as well as the radical lens of their punk contemporaries.

'80s punk and hardcore in LA traded back and forth with British punk in the same time period, where The Clash were getting heavily into ska and reggae. British anarchist punks Subhumans were also borrowing from reggae and ska rhythm at this time, eventually spinning off into slightly-mellower-but-still-anarchist ska band Citizen Fish circa 1990. But as the style caught on with totally new American audiences, according to Vice, the radical message of the music would again become diluted. And because 2 tone had been a more whitewashed ska scene, the American counterpart took off from there and continued the pattern, even when it utilized the diverse influences of Southern California.

The third wave of ska launched it into the mainstream

By the early to mid '90s, ska had become ubiquitous in mainstream American rock music. Bands like Sublime, No Doubt, Sugar Ray, Mighty Mighty Bosstones, The Toasters, Hepcat, and even Smash Mouth coasted to third wave fame on its chipper brass sounds and cutting rhythm (not to mention the Latino musical influence in the many Southern Californian ska bands). As explained in Vice, it also quickly became an easy target for mockery by music snobs, and with arguably decent reason, since the once-politically charged music was now becoming the soundtrack to goofy and often nonsensical themes.

Even within this modern take on ska, which was far-removed from its '60s roots, there were separate, distinct Jamaican rhythms heard from punk bands on American radio. In a 1998 article for the Washington Post, Mark Jenkins broke down the different working pieces of ska-punk and its explosion in popularity at the time. The classic ska rhythm was playful and springy, mirroring the optimistic mood in Jamaica around the early years of independence from Britain. Reggae, on the other hand, favored a more slow and loping rhythm, conveying a disappointed political outlook and message. Back in the '80s, dancehall had made a splash in Jamaica with its blend of hip hop and reggae foregrounded by deejay-rappers known as "toasters." One of the major cult figures in dancehall, Super Cat, wound up being heard by basically every American in the Sugar Ray song "Fly."

Ska's fourth wave is just getting started

While it's easy to assume ska died post-'90s, it mostly just went underground while staying active in places like Mexico and Los Angeles. However, we're probably a ways off from hitting anything like peak third wave ska numbers, like in September of 1998 when four different ska bands made it to the top 20 on the Billboard alternative chart. Still, American ska mainstays like Reel Big Fish continue to perform to huge audiences today.

According to Billboard, what's been called a fourth wave as recently as summer of 2019 (when The Interrupters became the first American female-fronted ska band to have a radio hit since No Doubt) is drawing on the original Jamaican ska of the '60s plus the huge American third wave influence. Interrupters frontwoman Aimee Allen, in the Pick it Up documentary, says it best: "Ska never went away, it just dips in and out of the mainstream." Whatever happens with the future of ska music, it will definitely continue to produce earworms as highly-charged as they are catchy.