The Messed Up Truth About Native American Reservations

Native American reservations were built on a messed up history of colonization by an invading government. Reservations themselves are a reminder that the United States sits on stolen land through attempted genocide and rose to its heights on the backs of broken treaties. Reservations symbolize the killing of whole traditions and languages; the end of the old Indigenous way of life and the start of a new one controlled by an uninvited force.

It may sound like all of this is ancient history but much of it resonates today. The treatment of Native Americans in society and the treatment of sovereign tribes by the U.S. government rarely make it into the news, but both bring an entirely new definition to the phrase "sub-par." Reservations have changed since their implantation, but not really for the better, and it usually involved increased control by the federal government or further encroachment on treaties. There's a reason why we hear little about reservations in history class: it isn't pretty.

An attempted genocide

In the course of colonizing the United States, the majority of Native tribespeople who inhabited the lush, resource-rich land were killed. Technically, anything over 50 percent could be considered the "majority," and even that would be catastrophic. Most sources believe the death toll was even higher than that and took out nearly the entire indigenous population of North, South, and Central America.

Some of the indigenous people killed were outright murdered in the name of westward expansion, while others would be considered casualties of war — wars in which the Native people were fighting for their lives the same way anyone would when an invader robs them of their home and traditional ways. It seems the largest portion of the deaths came from diseases brought with Europeans from their alien land. Never encountering these diseases before means the Native people never had the evolutionary opportunity to develop the herd immunity necessary to avoid broad catastrophe. Now, colonizing Europeans didn't have a great grasp on microbiology, but they soon learned that smallpox was devastating to the Native Americans and didn't hesitate to spread infections.

The overall body count is hard to determine. According to a publication by the University of Houston, the Native American population reached its lowest numbers at the turn of the 20th century with less than 250,000. The population before white colonizers has been estimated as high as 145 million.

The Indian Removal Act

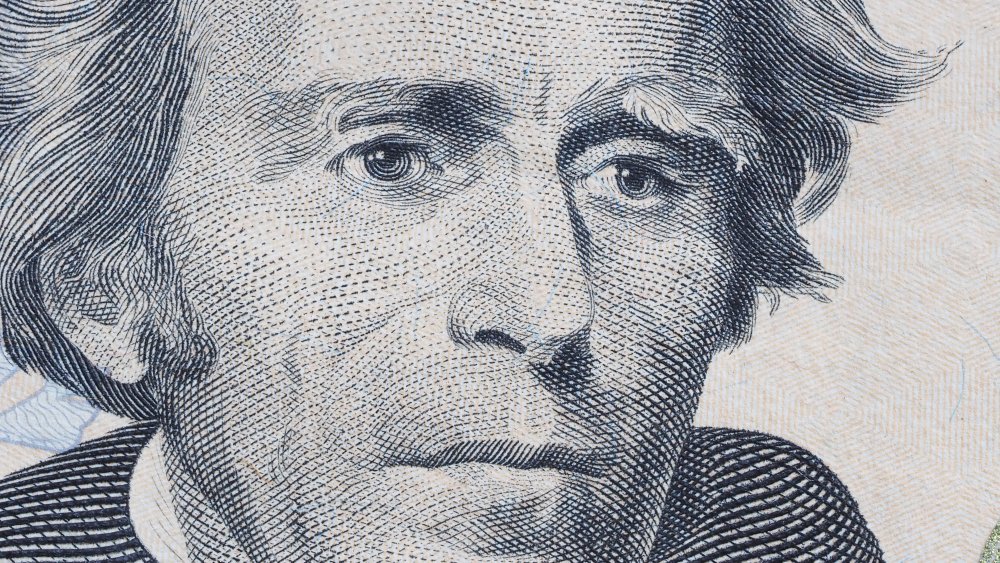

The Indian Removal Act, put into place in 1830, has been said to be the first grand attempt by the United States government toward respecting the rights of indigenous people, according to Encyclopedia Britannica. Here's the thing though: it wasn't. The policy and implementation were as crappy as the name makes them out to be.

The act was signed into place by President Andrew Jackson. It's the reason why many white people mistakenly think Jackson was a hero to the Native American tribes. If you only look on the surface, you can see why. The act promised to pay Native inhabitants east of the Mississippi River for their land and grant them other lands in the West. Jackson took it upon himself to promote the act with everything he had, but all the act did was screw over the Native peoples while limiting violence and resistance.

The land the Native Americans were promised was hundreds of miles away in Oklahoma. As you can imagine, the Eastern tribes weren't given a choice. They were forced away from their farms and settlements on treks that would be dangerous, ungodly far, and cost many Native people their lives. For instance, the Trail of Tears was among these treks and cost the Cherokee tribe around 15,000 lives.

The Indian Appropriation Act

Native American reservations exist through the formation of treaties between the colonizing United States government and the Native tribes that inhabit each of the reservations. Bureaucracy requires all agreements and actions to be driven by pieces of paper. Every act is signed into place, every agreement is documented, etc. As far as the government is concerned, if it isn't on paper it's not real. This includes the Indian Appropriation Act. The act that ended treaties.

As Indigenous people were being driven to new locations under threat of force, having their resources stolen, and their land transformed, they took a rational stance akin to "oh, hell no." Treaties had been signed before, but they were rarely honored. Wars broke out. The US government was tired of the resistance and had to rationalize their own underhanded behavior. That's where the Indian Appropriation Act of 1871 comes in. The act didn't just stop treaty-making. It stripped away the previously established classification of Indigenous tribes as independent nations. This made them exempt from future treaties and took away the sovereignty that had been recognized since the beginning of colonization. According to American Indian magazine, Congress did say they'd honor treaties made up until that point. But, of course, they wouldn't.

Broken treaties and dwindling of promised lands

The United States breaking treaties with indigenous Americans is a tradition that began when the US government first started making treaties and has extended through — well, it's still going on today. Granted, in 2020, the Supreme Court deemed 3 million acres of eastern Oklahoma land as belonging to Native American tribes per treaties signed after the 1830 Indian Removal Act, but that's only a single case and doesn't exclude more than a century of the treaties being dishonored. The treaties signed after that 1830 were broken by settlers who moved west and began taking up residence in OK shortly after they were signed. Tribes in other areas haven't had the same luck with the Supreme Court.

Encyclopedia Britannica says the Great Sioux Nation, for example, was originally promised over 60 million acres of land with the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie only to see the land dwindle to less than 13 million acres when the General Allotment Act was passed nine years later. When the Sioux went to court to demand the return of seized land over a century later, they were offered monetary compensation for land they never intended to sell. What's worse is the Supreme Court decided in two separate decisions (1902 and 1903) that it was cool for the US government to change or break treaties whenever they felt like it.

Native American reservations were a way to force assimilation

Reservations provided more to the United States than a place to relocate displaced Indigenous people. They served as a mode of forced assimilation. When reservations were originally put into place, Christian missionaries would flock to them and try to up their conversion rate but often fell short. Most of the Native peoples would choose to retain their traditional religions for as long as possible, but their traditional ways wouldn't remain safe from their white colonizer's thought attacks forever.

Reservations took a toll on the minds, economy, and health of the people who were forced onto them that directly led to increased rates of disease and alcoholism. The Indigenous people who lived there were dependent on the government. Such is a problem when one loses the ability to perform their traditional subsistence activities. According to History, the government enacted the Dawes Act of 1887 in an attempt to limit this dependency. The act granted 160 acres to each indigenous family for farming and would give citizenship to participants after 25 years. The land was Western land though, which made it extremely difficult to farm, and much of it was sold to the railroads and white settlers.

The money from land sales was used to fund reservation schools, which in turn were used to force the assimilation of Native peoples into Western cultural ways. Indigenous children were required to cut their hair, speak English, and abandon their traditions. Any student who didn't show up to class would be visited by truancy officers.

Police brutality on Native American reservations

Police brutality is nothing new to Native Americans, on or off the reservations, but it rarely hits the news stations. In fact, Native Americans are more likely to be killed than any other racial demographic in the United States. According to a CNN breakdown of CDC information, Native Americans were three times more likely to be killed by police than white people and were 12 percent more likely to be killed than Black Americans. The number of Native people killed by police has been increasing with 13 Indigenous people killed in 2015 and 24 killed in 2016, according to the Lakota People's Law Project and, according to CNN, the numbers have likely been underreported.

Of course, this news has only recently made a few headlines as the American people saw the American Indian Movement flag being flown during the George Floyd protests across the country. There's a reason for it. The American Indian Movement standing in solidarity with Black Americans over police brutality is completely in line with AIM's origin story. The organization was born to combat police brutality in the Twin Cities in the '60s. From there, the organization has protested Native American mistreatment with some pretty big moves, including taking part in the Occupation of Wounded Knee and the Occupation of Alcatraz Island.

Native American reservations have violent crime and justice issues

Tribal lands have a high rate of serious crimes such as rape and murders, as well as a high rate of missing persons, but they don't have a high rate of tribal members committing these crimes. It has to do with the way the United States government allows reservations to investigate and prosecute crimes as much as it has to do with inefficient bureaucracy. In Montana, where Indigenous Americans make up less than 7 perfect of the population, they account for over a quarter of the total missing persons within the state, according to the Billings Gazette.

According to the Atlantic, a proportion of crimes perpetrated on tribal lands get lost in the judicial system. For example, they found that around 65 percent of rape cases that were reported on reservations in 2011 never got prosecuted by the U.S. Justice Department like they were supposed to. It becomes obvious how this happens when we look at legal structures surrounding reservations. This is how it's set up: If the victim of the crime is a tribal member but the perpetrator isn't, they can only be arrested by a federal agent; if both are non-members, they can only be arrested on the state or county level; and if a tribal member commits a crime on a reservation, they can be prosecuted by the tribal justice system.

Rampant poverty plagues Native American reservations

Structural poverty plagues the Native American reservations, keeping them near the bottom of the poorest places in the United States. Forbes puts many of the Native American reservations within the bottom 1 percent of the economic ladder and, according to Native American Aid, between 38 percent to 63 percent of tribal members living on reservations live below the poverty line. Native American and Reservation poverty seems to be a result of design, though one could argue that it was a result of ignorance or poor foresight.

The Indigenous people of America didn't live by the principle of land ownership that forms the basis of Western economies. Land and resource ownership, versus communal use, was forced on Native people and required the shifting of Indigenous worldviews for survival. The land given to them through treaties was often unfruitful and devoid of resources. When resources were discovered on reservation lands, the United States would commandeer the resources if not the land itself. Natives were offered no opportunity to amass any real material wealth. In the modern era, things haven't changed much. Most reservation land is communally used while being legally owned by the U.S. government, according to Indigenous Peoples Major Group for Sustainable Development, and without property ownership, tribal members often don't have the collateral required to take out loans and build credit.

Increased suicide rates

Suicide rates are higher among Native peoples than any other "race," and those rates have risen by 33 percent from 1999 to 2019 according to USA Today. Among those suicide deaths, nearly one-third were young, ranging from 10 to 24 years of age. The Fort Belknap reservation in Montana declared a state of emergency in 2019 after 15 youth suicide attempts in a single month. The Lakota people went through an obscenely high wave of young member suicides on the Pine Ridge reservation from December 2014 to March 2015. During that time frame, 109 people between 12- and 24-years-old had attempted suicide and nine succeeded. Pine Ridge is one of the poorest places in the United States.

Poverty rates of greater than 20 percent in a single county have shown an increase in suicide rates of up to 37 percent, according to U.S. News. With the high poverty rates on reservations, it's easy to blame the poor economic status for the suicide rate, but it's not the only factor. Police brutality, racism, and lack of cultural identity all have severe effects on mental health. The high suicide rates on reservations aren't just an economic factor, though that certainly plays a part, it's an overall product of colonization.

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Native American land rights are blatantly ignored

By the 2020s, you would think, certainly, any individual in the United States has the same legal rights as everyone else, right? If that were the case, we wouldn't see Native American reservations in the news for protesting petroleum pipelines being put through or fracking commencing on tribal lands without the reservation's consent. Unfortunately, it happens all the time. Tribal land rights are blatantly ignored, especially when money is on the line.

Older examples would include breaking land treaties, the seizing of the Black Hills, and carving the faces into Mount Rushmore. No need to look that far into the past. Just a hop away is the Dakota Access pipeline running right next to the Standing Rock reservation and threatening their water supply, according to the New York Times. The pipeline has been stopped and started enough to turn heads. A gas pipeline going through Kiowa land in Oklahoma stayed in place more than a year after it was ordered to be removed within six months. The Keystone XL pipeline from Canada is being built through Rosebud Sioux land in a move that blatantly goes against the Treaty of Fort Laramie. There's fracking on Pawnee land. There are plenty of other examples, but you get the general idea.

The definition of 'Sovereignty' is always changing

Before white colonizers started invading the Americas in the late 1400s, the Indigenous tribes were truly sovereign. They were individual nations living in individual governments and could make their own rules. That all changed of course. Even after the United States had become a country, the Indigenous nations were still recognized as truly sovereign. The right was guaranteed via numerous treaties.

After reservations were established, tribes were still considered sovereign people living within the borders of a different nation. The Indian Appropriation Act of 1871 stripped them of that classification and guaranteed the U.S. government didn't have to enter new treaties from then on out. That act preserved the treaties and sovereignty that were in place previously. The 1953 House Concurrent Resolution 108, on the other hand, cut U.S. treaties with 100 tribes, stripping them of treaty-protected sovereignty, according to the Washington Post, and took tribal birthright away from over 12,000 Indigenous people in America.

The Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 gave some control back to reservations by determining that they could contract to the Bureau of Indian Affairs to establish some of their own government functions, such as police departments and courts. It's hard to determine the level of sovereignty given to reservations since it seems to change via Supreme Court determinations and congressional acts at the whim of the United States at any given time.

Atrocities committed against reservations rarely make it into mainstream media

Unless Native Americans are actively involved in a major protest, they rarely make it into the mainstream media. When they do happen to, they're often misrepresented. Why? One of the reasons amounts to there being far too few Indigenous American journalists and far too many white journalists that have no idea what actually happens on reservations. Nor can these non-Indigenous journalists necessarily empathize with the struggles that Native peoples face in their daily lives. According to the Columbia Journalism Review, Native Americans are often blatantly left out of the conversation.

Beyond that, Native American history is rarely taught in schools and when it is taught, it's done so from a white perspective that falsely makes the Pilgrims and Christopher Columbus out to be heroes. News stories will break covering the poverty of the inner city, but we rarely hear about the poverty that's afflicted Native American reservations from day one. On a basic level, the United States and white people don't want to draw attention to the tragedies we've created. We ignore them, along with the Native people themselves, as Cultural Survival points out, or we sweep them under the rug out of ignorance. We focus on the parts that don't make us look so bad. Not on broken treaties but on returning a sliver of the land. Not on an attempted genocide but on Indigenous protest. And, it won't stop until the nation can face its own ongoing participation.