Everything You've Ever Wondered About The Dead Sea Scrolls

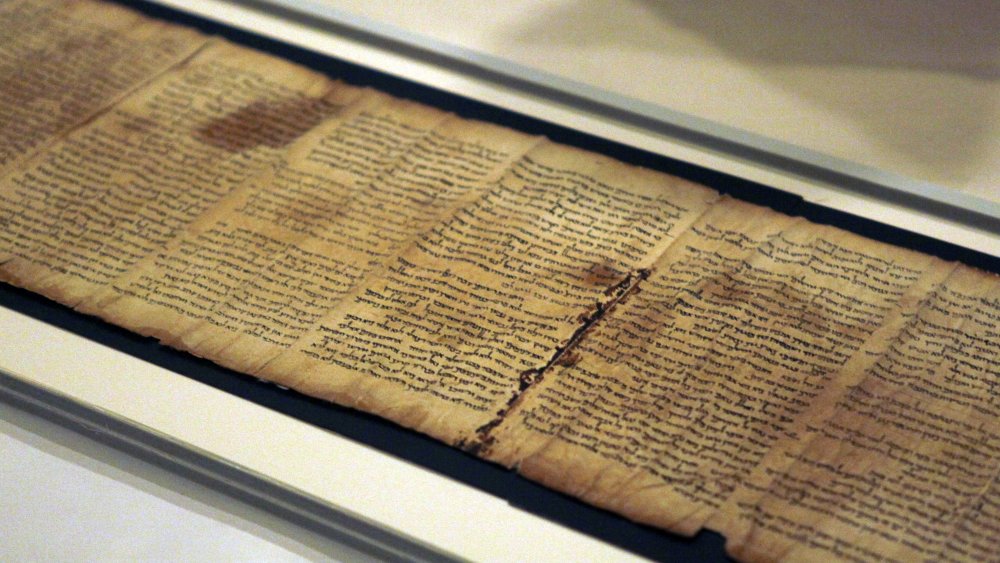

When it comes to ancient religious texts, the Dead Sea Scrolls are among the most important — but they're so much more than that, too.

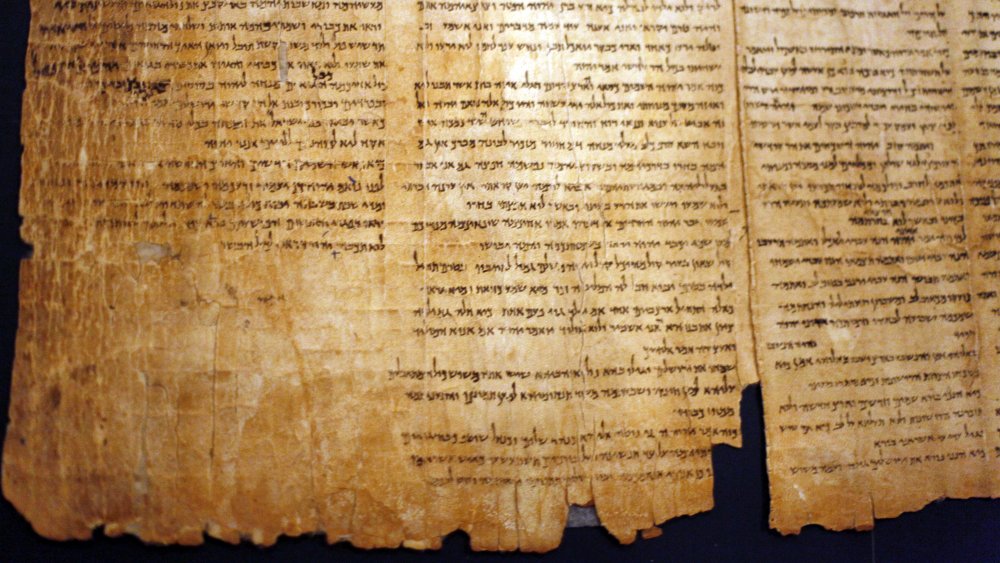

First, the basics. According to The Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library, which is a part of the Israel Antiquities Authority, the scrolls not only contain both religious and secular writings that give us an idea of how long certain practices and beliefs have been held, but they also contain religious information found nowhere else, along with some secular writings that have given us a glimpse into ancient everyday life. Pretty cool, right?

While there are a few intact scrolls, there are others that are in thousands of pieces — and putting them together has been something of a challenge. That's not just because of the sheer number of pieces: The scrolls were written between the third century BCE and around 70 CE, and they were written in Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic. Imagine trying to put together a 10,000-piece jigsaw puzzle with no reference picture and 20,000 pieces to choose from, some of which might disintegrate if you look at them funny. So ... what have we learned?

A chance discovery ... for sale in the classifieds

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls gives us hope that there's still some very literal buried treasure out there, and we might be as lucky as a Bedouin shepherd ... someday.

According to the Israel Antiquities Authority and The Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library, this is the story that's most often told about the discovery of the scrolls: In 1947, a Ta'amireh tribe shepherd wandered away from his flock, looking for a stray sheep. He stumbled across some caves and tossed a stone into the darkness. Instead of the sound of rock hitting rock, he heard pots break. When he went in to figure out just what was in the cave, he found a group of large clay jars, and in some of those jars were old scrolls.

He took the scrolls to an antiquities dealer in Bethlehem, and after traveling through a number of hands — and being sold through an advertisement in the classifieds section of The Wall Street Journal – seven of the scrolls ended up at the Hebrew University. Meanwhile, excavations were started to try to find more, and find more they did. So far, archaeologists have found the remains of more than 900 individual manuscripts, hidden in the caves of the Judean Desert.

Who wrote the Dead Sea Scrolls?

That, dear reader, is the million-dollar question, and it's a doozy — especially considering that the Dead Sea Scrolls predate the next oldest known Hebrew text of the Jewish Bible by a good eight to 11 centuries, per Smithsonian Magazine. There's a ton of debate as to who wrote them, so let's look at some of the biggest theories.

One suggests that the settlement where the scrolls were found was the home of a sect of Jewish ascetics. They were the Essenes, and their entire lives were dedicated to copying, writing, and preserving sacred texts — something they had been doing even before Jesus arrived on the scene. When the Romans showed up and destroyed their home, they stowed the scrolls in the cave for safekeeping.

That's one theory, but some experts don't buy it at all, saying there's little to no proof that the Essenes had anything to do with the scrolls. Those experts think that the nearby settlement was more of a fort than a library and that it was a group of Jews fleeing ahead of a Roman rampage who stashed the documents they'd collected ... in the cave for safekeeping. At least they agree on that part.

Figuring out who wrote the scrolls may provide a fascinating early link between Christianity and Judaism: It's believed that if the texts were written by the Essenes, that suggests John the Baptizer — Jesus' teacher — learned from them.

Wait, there's a whole settlement there?

We usually just hear about the Dead Sea Scrolls being found in a cave in the desert, and that's true. There's more to it, though: There's a whole settlement that has been excavated in the surrounding area, and it might hold valuable clues about the people who wrote — or at least protected — the scrolls.

Qumran Park is at the foot of some terrifyingly steep cliffs sitting on the shores of the Dead Sea. According to the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, excavations have found what seems like a very communal sort of place: There are meeting rooms, a communal dining hall, and a series of "purification pools" where people would gather for ritual bathing. There are some standard buildings for the era, too, like a kitchen and stables, but there are some fascinatingly strange ruins, too. One of the buildings excavated is a scriptorium, which included scores of pottery and metal inkwells and hundreds of pottery lamps. Is that where the Dead Sea Scrolls were written? No one can say for sure.

The Times of Israel says that the area (Qumran and the series of caves in the hillsides above) has been inhabited for a long, long time. Prehistoric objects such as arrow and spear heads have been found, and here's the odd thing: Carved pieces of obsidian have also been found there, and the closest place they could have come from is what's now Turkey. Was this place more important than we think?

What do the Dead Sea Scrolls say?

Not all of the Dead Sea Scrolls are religious texts, and The Leon Levy Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library says they're divided into "Biblical" and "Non-Biblical" categories, along with "Unidentified Texts," which is basically a category for the pieces that are too small to be read.

So, what does that all mean? Within the Biblical category, there are a whole slew of different texts. A huge portion is dedicated to the text of the Hebrew Bible, and every book — except the Book of Esther — has been found within the scrolls. There are also tefillin (which are small scraps of paper designed to be folded and carried with you), translations of scripts into Greek and Aramaic, and mezuzot — passages found on doorposts of houses, something that is still done today.

Then, there's the non-Biblical stuff. Those are texts like the Apocrypha, which are scriptures that used to be canonical but are no longer considered so. There are also calendars, analytical texts, historical texts (that deal with things like religious and civil laws and ethics), poems, texts that offer advice on daily life, and something called "Parabiblical" texts, which expand on biblical stories.

Some scrolls are none of the above: There are also 15 military letters, the personal documents of Babatha, a refugee from the Bar Kokhba Revolt, and the personal papers of a farmer named Eleazar, son of Shmuel.

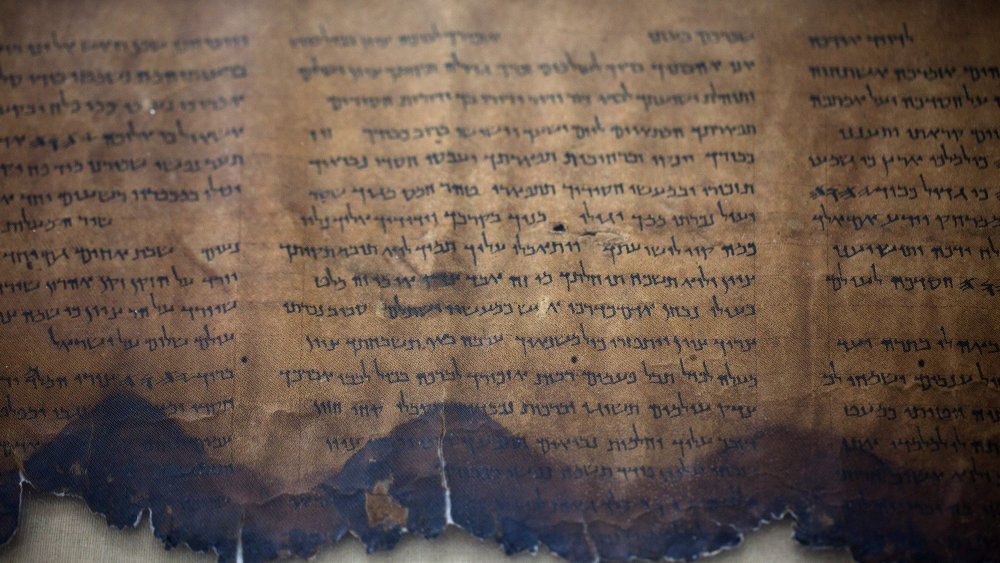

The largest of the Dead Sea Scrolls: What does it say?

While there are plenty of texts that are in fragments, there's one Dead Sea Scroll that's not just complete but huge. It's called the Temple Scroll: It contains 18 parchment sheets, and it's a shocking 26.7 feet long. According to The Israel Museum, it's thought to be a copy of a manuscript originally written after or around 120 BCE.

So, what's it say? The scroll describes a massive temple compound, made of three square courtyards that are meant to represent the desert camps of the Israelites, as described to Moses by God Himself. The BYU Religious Studies Center says it's very specific: The scroll details things like the proper way to slaughter sacrificial animals, the way tithing should be done, how priests should perform ritual ablutions, and even how to affix spikes to the walls of the compound to keep the birds away.

That sounds odd, but the reasoning is that birds will poop pretty much everywhere, and the scroll is, well, a little obsessive about cleanliness. Not only does it detail how long those wanting to go to the temple should abstain from sex, but it also goes into an explanation of why there should be no toilets in — or even within sight of — Jerusalem. The waste products of the human body are so impure that toilet facilities should be at least one mile from the city. Strict? Absolutely — more strict than the regulations put forward in the Torah.

The Dead Sea Scrolls' prophecy of war

Mankind, it turns out, has been thinking about the end times since, well, pretty much the beginning of times, and even the Dead Sea Scrolls deal with what Armageddon is going to be like.

That is what's on the aptly named War Scroll (as detailed by PBS), a text that starts out by describing a massive confrontation that lasts more than 40 years ... so, we have that to look forward to. The Sons of Light — members of the "Yahad" — are going to take on the Sons of Darkness, which are an alliance of biblical baddies. After years of fighting, it's all going to come down to one last battle. That battle, the scroll says, will have six horrible and bloody engagements, with Light winning three and Darkness winning three. The seventh confrontation will be the last, and that's when "the great hand of God shall overcome."

Along the way, there are plenty of heavenly trumpets, prayers for salvation, and complete destruction of all that is evil at the end of the day. There's one more day mentioned — a day of thanksgiving and a ceremony of celebration. That's good news, but here's the thing: There are a few lines missing at the very end of the text. And that? That's not the kind of thing you want to go missing.

One scroll is a detailed treasure map no one's been able to solve

In 1952, archaeologists found what might be the coolest of the Dead Sea Scrolls: a treasure map, etched into copper. According to the Biblical Archaeology Society, the scroll describes a series of between 61 and 64 locations across Judea, along with what's hidden there. Given the massive size of the treasure, it has long been believed to be a map to the contents of the Temple in Jerusalem, and what's that?

According to Interesting Engineering, the Second Temple was built between 516 BCE and 70 CE, which is significant: the 8-foot-long scroll has been dated to around 70 CE, the same year Roman soldiers sacked the temple and destroyed much of Jerusalem. In the years leading up to its destruction, visitors to the temple were required to leave an offering: half a shekel, or around 7 grams of silver. That piled up, and it's thought that much of the treasure was whisked away by priests, who buried it around the Holy Land and left clues in the Copper Scroll.

Some of the places mentioned have been excavated, but none of the treasure has ever been found. One possibility is that after the Romans left, the treasure was immediately retrieved. Another is that we just don't know where some of the locations in the translations are: Maybe we're not digging near the right "old Washers House." Maybe the translation is wrong? Maybe there's a code? We want to know!

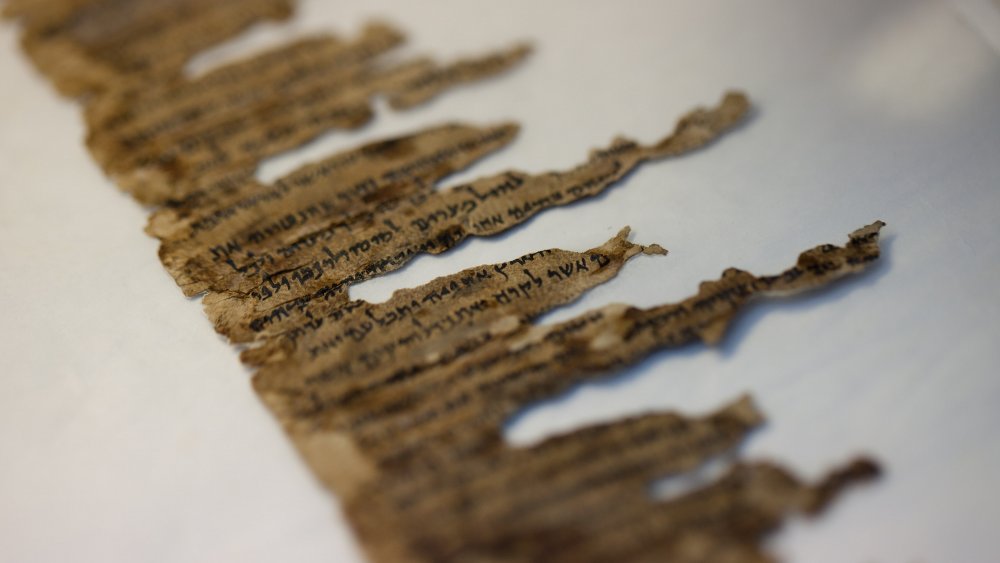

The 364-day calendar of the Dead Sea Scrolls

In 2018, National Geographic announced that researchers at Israel's University of Haifa had restored and translated one of the last remaining mystery scrolls in their collection. It was in 60 pieces, and it took more than a year to reassemble and translate. The result? A 364-day calendar that included new details on seasons, celebrations, and harvest festivals.

Included was a little more information on two particular festivals: New Wine and New Oil. According to the text, those particular festivals were celebrated along with the Jewish harvest festival of Shavuot and took place, respectively, 100 days after the first Sabbath of Passover and 150 days after. According to TheTorah.com, the festivals were held in celebration of two of God's most important gifts — wine and olives, or oil. Also new? The name of celebrations marking the changing seasons, known as Tekufah.

Also significant was the idea of a 364-day calendar. Because that number can be divided by seven and four, special occasions and celebrations always fell on the exact same day, making for an unchanging calendar. With the translation of this scroll, that left only a single known scroll still untranslated.

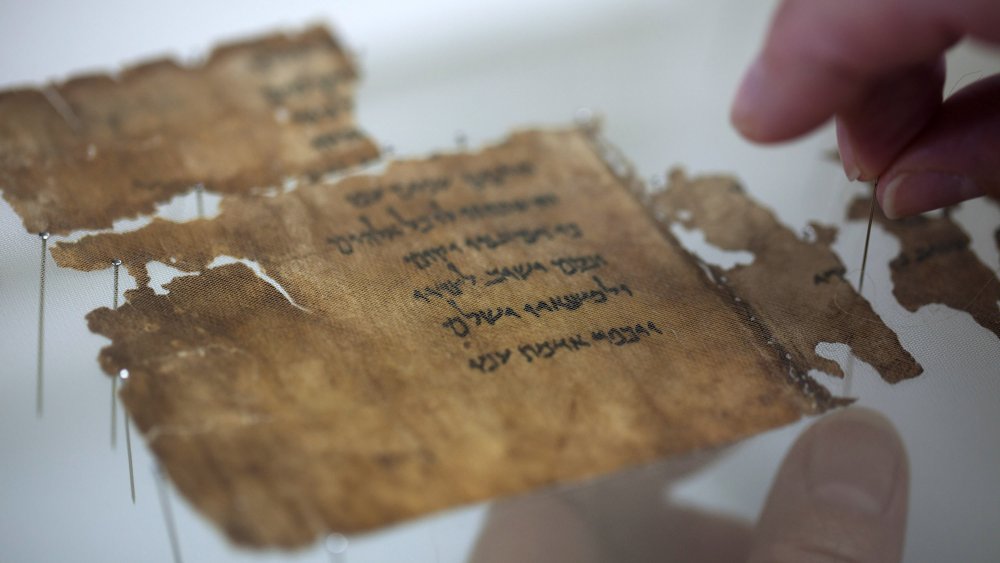

Animal DNA is proving to be a big part of solving the puzzle

In 2020, National Geographic announced that something pretty unusual had been used to try to learn more about the scrolls and their origins. The scrolls are, for the most part, written on parchment. That parchment is made from animal skins, and when a group of researchers did some DNA testing on the parchments, they found some pretty bizarre things.

For starters, they determined that two pieces long considered to be part of the same scroll, the Book of Jeremiah, were actually written on two different types of animal hide and couldn't be part of the same scroll after all. Oops!

They also found a shocking variety of animal DNA, and when they looked at the genetic signatures, they were able to see if parchments came from animals in different herds. When they separated texts by similar styles of writing, they found that these similar texts tended to be written on parchments made from related animals. It also seemed to confirm the idea that the texts — or at least the parchments — came from different regions across Judea, and that's pretty neat.

Here's why a bit of salt has caused such a fuss

Advances in science have allowed us to do a bit more testing on the fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls, and in 2019, researchers got a bit of a surprise when they looked at the methods that had been used to preserve them.

According to The Guardian, researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology looked at the Temple Scroll, and when they started looking at the actual make-up of the ultra-thin parchment, they found that the writing had actually been done on the outer, skin side of the parchment, which is odd. Also, it had been whitened through a method of treating the skin with salt. Researchers likened it to writing on top of a layer of plaster applied to a wall.

That's neat, but they found something weird, too: The salts used in the preparation of the parchment weren't native to the Dead Sea, and researchers weren't sure exactly where they had come from. Were the scrolls written on parchment prepared elsewhere, or did they rely on ingredients shipped in from afar? The mysteries keep mounting.

Washington D.C.'s Bible museum was duped by forgeries

Among the prized exhibits in Washington D.C.'s Museum of the Bible were 16 fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls ... until 2020, that is. That's when National Geographic says the museum went public with the finding that their scroll fragments were fakes.

Their fragments were some of about 70 that first showed up in the antiquities market in the 2000s, and for a long time, scholars have suspected there was something fishy about them. But still, the Museum of the Bible didn't send five of their fragments off to Germany's Federal Institute for Materials Research for confirmation until 2017, and in 2018, they got the results they didn't want: fake. Then, when all their fragments went through more testing ... yep. All fake — they weren't even made of the same sort of lightly tanned or tanned parchment known to be used in the other scrolls.

Strangely, the leather of the scrolls is from the right era, and researchers even guessed that some of it had once been part of Roman-era shoes. And that presents a larger problem: Where did they come from, and are there more fakes out there?

There may still be more Dead Sea Scrolls out there

Here's a question: Is it possible that there are still more Dead Sea Scrolls out there? In short, yes.

In 2016, the Israel Antiquities Authority announced (via Live Science) that they were officially establishing a program that would locate and then excavate new caves in the same area as those that had already yielded the scrolls, and they were sort of in a hurry to do it. Why? Looters had recently been busted with new fragments.

A new cave was discovered in 2017, and that one yielded a blank scroll, some jars, and leather straps ... just like the ones that would have been used to wrap scrolls. The cave had already been looted a long time ago, judging from the 1950s-era pickaxes. At the time, National Geographic reported that there were somewhere around 50 more sites that archaeologists had targeted as promising locations for more Dead Sea Scrolls and biblical-era relics, so who knows what the next cave will bring?