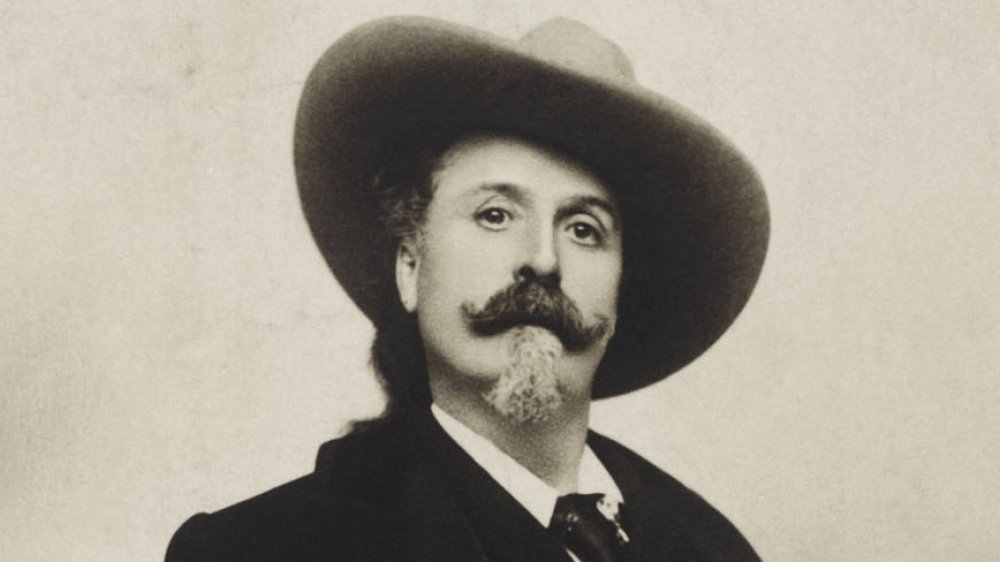

The Tragic Final Years Of Buffalo Bill

If you love a good Western (or even a bad Western), you owe a debt to two men: E.Z.C. Judson and William F. Cody. The first helped invent the second, but the second took the idea and ran with it for decades, building his image into a traveling extravaganza that entertained not only the United States, but Europe as well.

First there was Cody, born in Iowa in 1846, as PBS tells us. He was just 11 when his father was murdered for making a speech in opposition to slavery, and young William became the main source of income for the family. He became a teamster and cattle drover, did some prospecting and trapping, hunted and might even have been a rider for the Pony Express. We do know that Cody rode in the Union cavalry during the Civil War, per All That's Interesting, then continued afterwards as a scout. And a hunter. The railroads were pushing west, and it was Cody's job to supply meat — in this case, buffalo. According to his own estimate, he killed more than 4,000 of the animals during his time as a professional hunter, says Biography. That isn't why he was nicknamed Buffalo Bill; that came as a result of a hunting contest with another William. (Cody won.) Remember Cody was hunting from horseback, often at a dead run, firing a single-shot .50 caliber black powder rifle.

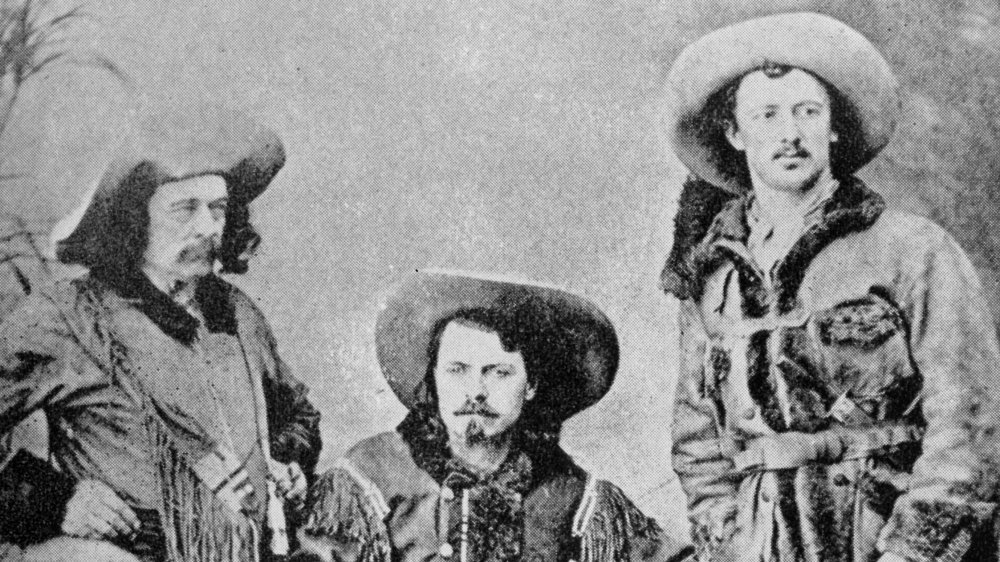

Ned Buntline (left) wrote; Cody and Texas Jack Omohundro tried to act

He also went back to work for the army as a scout, participating in several battles and awarded the Medal of Honor. (It was revoked in 1916, not because he wasn't heroic, but because he wasn't a member of the armed forces at the time. It was reinstated in 1989. The same thing happened to Mary Edwards Walker.)

Cody always had a flair for the flamboyant and told a good story. E.Z.C. Judson, writing under the name Ned Buntline, knew a good story when he heard it and started writing about the daring exploits of "Buffalo Bill" in newspaper serials and dime novels. He expanded his repertoire with a stage play he concocted, starring Bill, says History. By all accounts Cody wasn't much of an actor (and it wasn't much of a script), but he had that indefinable "stage presence" and had an instinct for working an audience. The show quickly turned into more improv than anything ("Did I ever tell you about the time....?").

There was money to be made in playing dress-up and fewer chances of getting shot. Cody struck out on his own. So what if it wasn't historically or even culturally accurate — people loved it and were willing to pay to see it.

Annie Oakley was one of Cody's star performers

Cody developed a traveling show — part circus, part rodeo, part highly inaccurate history lesson — a Wild West Show and Congress of Rough Riders, with riding exhibitions from cowboys, Native Americans (Sitting Bull toured for a season), and other equestrians from around the world, as well as trick shooting by people like Annie Oakley. Cody took the show to Europe and performed for Queen Victoria, who was so taken by the spectacle she asked for a repeat performance.

Cody was complicated, and while a man of his times, was ahead of the curve in many ways as well. Smithsonian quotes an April 16, 1898 interview Cody gave to The Milwaukee Journal, in which a reporter asked Cody if he supported women's suffrage. "'I do,' the famous showman responded. 'Set that down in great big black type that Buffalo Bill favors woman suffrage.... These fellows who prate about the women taking their places make me laugh.... If a woman can do the same work that a man can do and do it just as well, she should have the same pay.'"

Cody lost his Wild West show through bad business deals

With all of the success, the fame, the acclaim, the touring, Cody should have been financially secure. Unfortunately, he fell victim to himself. Like many frontiersmen, he liked a drink or two. He was always known as a soft touch — generous with his employees, willing to help someone with a hard-luck story. He also fancied himself a man of business, investing in land deals that cost him money instead of earning it. Mining interests were also failures. Finding himself short of cash to keep his traveling show going, he accepted loans from two Denver businessmen of less than stellar reputations, writes True West Magazine. A poor season meant Cody couldn't repay the loans and had to relinquish control of his own show. By 1914 he was simply another employee — his name on the posters, but no longer his production. He kept it up for two seasons, exhausted — he was pushing 70 — but finally parted ways. He worked for other traveling productions, but died, nearly penniless, in 1917.

Unlike many figures from the Wild West, there's actual footage of Buffalo Bill at work and at play — this one characterizes him as "The Idol of Young America," and this has footage of one of his later Wild West shows.