Why The Silk Road Was More Important Than You Realize

The Silk Road is traditionally thought to have "begun" around 130 B.C, when the Han Dynasties started trading with the west. But before this, traders were already traveling from the Horn of Africa across the Middle East and the Indian subcontinent, spreading goods and ideas. While the name "Silk Road" ("Seidenstraße") was coined by Ferdinand von Richthofen, a German geographer, after the popular Chinese silk that was traded across the routes, there were a variety of commodities that were exported and imported along the them. The Silk Road even provided paths for ideas to travel back and forth, evolving as they passed through different regions and cultures.

Xinjiang was one of the most important crossroads of the Silk Roads as most goods made their way in and out of China through the region, and due to its location it became a meeting point for the interactions of different religions and cultures. Some of the oldest mosques in the world once stood in Xinjiang until they were razed by the Chinese government in 2019 as a part of their attempted ethnic cleansing of Uighur Muslims. The Buddhas of Bamiyan are another example of the transference of religion across the Silk Road, in this case Buddhism. These statues were also destroyed, albeit partly, by the Taliban in 2001.

The Silk Road allowed for the spread of people, ideas, and goods, becoming possibly the earliest attempt at a global network. Here is why the Silk Road was more important than you realize.

By land or by sea

While the phrase "Silk Road" conjures up an image of a single road traversing across the Eurasian continent, historically the Silk Road was actually a network of multiple trade routes. On land, the routes were divided into the northern route and the southern route. Starting in the capital city Chang'an (now Xi'an), the northern route traveled northwest through the Shaanxi and Gansu provinces before splitting into three different ways around the Taklamakan Desert. The southern route passed through the Karakoram Mountains as it crossed through northern Pakistan and into Afghanistan, though this route was significantly longer. According to Against The Compass, today the Karakoram Highway stretches across the same route that historic merchants once journeyed along. Yet another route went through the southwest, across the Ganges Delta, from China to India.

Merv, Turkmenistan was one of the central meeting points of the northern and southern routes and, according to Atlas Obscura, was a major trading post on the Silk Road until it was destroyed in 1221 A.D. by the Mongol army.

A great deal of travel and trade also occurred by sea. The maritime routes had a plurality of ports spanning from Indonesia to India, traveling along the Arabian Peninsula and around the Horn of Africa. According to Medieval Indonesia, maritime trade contributed to the proliferation of goods more so than land trade in the Middle Ages.

Cities along the Silk Road

Merv was not the only oasis to thrive along the Silk Road. According to the International Council on Monuments and Sites, cities that developed along the routes were able to prosper not only through the economic trade, but through cultural and intellectual trade as well.

According to History Hit, Samarkand, Balkh, Ctesiphon, Damascus, and Taxila were some of the key cities on the Silk Road. Located in Uzbekistan in the Zerafshan River valley, Samarkand was a central trading post and was a city known for its craft production. According to UNESCO, Sogdian merchants are described in Chinese writings as early as 313 A.D., establishing an early network of trade. Other cities like Bactra (now Balkh in present-day Afghanistan) and Taxila (in present-day Pakistan) were cultural centers that proliferated learning and scholarly pursuits. One of the oldest universities in the world existed in Taxila in 500 B.C. and Bactra was a center of Zoroastrianism, having been one of the places where the prophet Zoroaster taught.

Since the Silk Road connected people from different cultures, languages, and religions, there was an astounding exchange of ideas within and between these cities. There was trade not only in products and technological inventions but in linguistic, astronomical, and philosophical ideas as well.

The Silk Road and the dissemination of religions

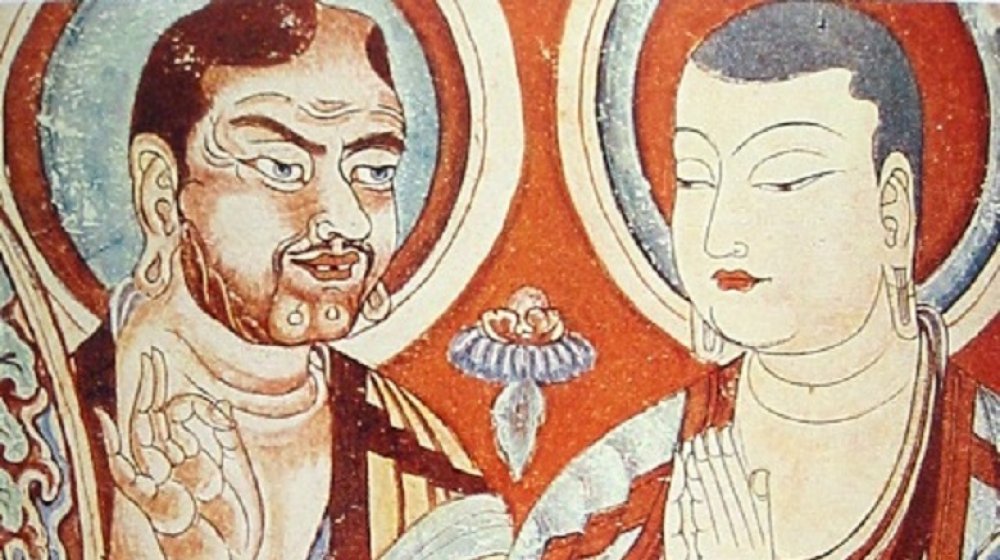

Religious ideologies such as Zoroastrianism, Confucianism, Islam, and Buddhism disseminated along the Silk Road. While the scale of ideological penetration varied and was dependent on a variety of factors, multiple religious ideologies evolved through their travels and interactions.

Buddhism spread out of the Indian subcontinent along the Silk Roads into China from the 5th century B.C. to the end of the 10th century A.D. According to The Silk Road: A New History by Peter Frankopan, while ambiguous source materials make it difficult to accurately track the movement of Buddhism, its adaptation, integration, and evolution through various ruling kingdoms is notable. As the spread of Buddhism accelerated in the 1st century A.D., Sogdian merchants were essential to carrying the religion out of the Indus valley and into China. The Sogdian people lived in present-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and through their trade and travel became a network connecting the disparate region. Sogdians were especially essential towards the proliferation of Buddhism. As Sogdiana prospered, its cities became centers of monastic activity and Buddhist texts were copied and translated into local languages, making the religion more accessible as it spread.

From its inception in the 7th century A.D., Islam made its way across Central Asia by land and to Southeast Asia by sea. According to Fruit from the Sands by Robert N. Spengler III, the dominance of Muslim merchants led to the religion's prominence in trading posts across West Africa, even if Islam wasn't the major religion of that region.

Trading horses for silk

Horses were not only essential for the transportation of goods along the Silk Road, but the modern-day horse may have arisen out of interactions on the routes. According to The Conversation, the genetic diversity of Central Asian horses can be tracked along the Silk Road, demonstrating that human trade affected the population-mixing of horses across distances of almost 8,000 kilometres. In the original paper published in Molecular Ecology, zoologist Vera Warmuth also incorporated landscape features into the consideration of the data, which demonstrated correlation between the genetic differentiation and the travel paths of the Silk Road.

According to the University of Washington, Central Asian horses were vastly superior to the horses raised in the Chinese lowlands. By the 2nd century B.C., the Chinese army was trading large amounts of silk to Central Asian nomads as payment for horses and camels as well as for keeping the peace. Camels were equally essential on the Silk Road due to their ability to survive in arid conditions. Due to their significance, both camels and horses were frequently celebrated in artistic representations spanning from China to Persia. The camel was so significant in the transport of goods along the Silk Road that art during the Tang period even depicts camels carrying loads of goods into the afterlife.

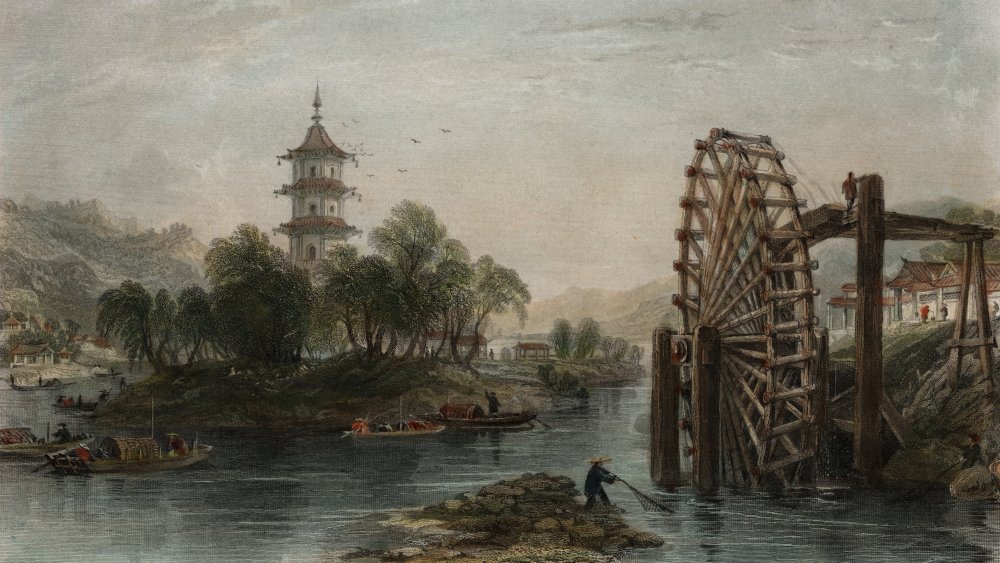

The watermill makes its way around the Silk Road

Technological developments and inventions also made their way along the Silk Road. Some of the most influential ideas spread were watermills and irrigation technologies. According to Monks and Merchants, the irrigation water wheel may have first been invented in Roman Syria and it was from this geographically central point that the technology proliferated across the Eurasian continent.

While the large rotary mill appeared in Asia and Europe around the same time in the 2nd century B.C., in China the watermill was widely used while in Europe the preference went towards dry mills powered by enslaved people or animals. According to the Washington University in St. Louis, archaeological remains of an irrigation system built in the 3rd or 4th century A.D. were discovered in Xinjiang, China, which bore many similarities to irrigation systems established further west, such as in the Geokysur river delta oasis in southeast Turkmenistan and in the Tepe Gaz Tavila settlement in Iran. By the beginning of the Tang Dynasty in 618 A.D, the watermill had spread from China to Japan and Korea.

Tea and coffee spill over

The southwestern path of the Silk Road was known more specifically as the Tea Horse Road. Traveling through Tibet, Yunnan, and Sichuan around Southwest China, the Tea Horse Road transported tea from some of the earliest tea-producing regions in the world. According to Nature Magazine, one of the first routes probably went through Tibet, since that is where the tea came from. The leaves were likely grown in order to cater to the tastes of the Han Dynasty, who ruled China from 207 B.C. to the 9th century A.D.

In Fruit from the Sands, Robert N. Spengler III writes that the Tea Horse Road was already well-established by the Tang Dynasty and had a number of trading posts. In addition to allowing a stream of goods into India, the Tea Horse Road also enabled trade with Tibet and China. According to The Horniman Museum, tea traveled through Kashmir, Kashgar, and Balkh as it made its way to Turkey by the 12th century A.D. Many of the regions that picked up the habit along the Silk Road engaged in similar customs and traditions around their tea drinking. It even started playing an essential role in business dealings and hospitality.

As tea made its way west, coffee made its way east along the Silk Road. The bean's travels can be traced from Ethiopia to Arabia around 575 A.D., into Persia around the 9th century, into Turkey around 1516, and into India by the 16th century. (It also made it west to the Netherlands by the 1500s.)

Gunpowder makes its way west on the Silk Road

According to LiveScience, gunpowder was accidentally invented around 850 A.D. when Chinese alchemists were ironically trying to invent a life-prolonging elixir. There's no evidence of its military application by the Chinese until almost 70 years later. According to the Silk Road Foundation, despite its application in bombs and cannons, the Chinese use of gunpowder was relatively crude and its military applications were soon abandoned.

But when gunpowder was introduced to the Eurasian continent by China it transformed the culture of warfare. Once it reached the Middle East by the 13th century, gunpowder was reapplied for military purposes. The earliest recorded account of gunpowder in Europe was in the 13th century by philosopher Roger Bacon, and it was almost immediately considered for its military applications.

Gunpowder was able to proliferate primarily as a result of the Mongol conquests and their reestablishment of the Silk Road, which had mostly collapsed when the Tang Dynasty fell. In this way, the Mongols' colonization inadvertently influenced the European's own age of colonization.

Wrapping up dough around the world

Ideological transfers weren't limited to technology or religion. Almost every Eastern European, Central Asian, Southeast Asian, and East Asian culture has come up with their own form of dough stuffed with meat. As with most products that flowed down the Silk Road, dumplings most likely originated in Xinjiang, China. According to The Silk Road: A New History by Valerie Hansen, the dry conditions at Turfan have even led to discoveries of preserved dumplings dating back to at least 700 A.D. It's possible that horsemen carried frozen dumplings with them during their travels, which is how they spread across the Eurasian continent. Chinese dumplings traveled down the Silk Road to become the various iterations we recognize today as Uighur manti, Indian samosas, Russian pelmeni, and Italian tortellini among others.

According to Reuters, stories around the foods bear similarities as well. Turkish and Italian traditions both include a story about daughters-in-law who, when married into a family, are judged by their ability to make manti/tortellini.

According to Fruit from the Sands by Robert N. Spengler III, the invention of noodles and dumplings was only possible because wheat was brought into East Asia from the west, originating in the Fertile Crescent. East Asia, in return, had previously introduced broomcorn millet into Europe, where it became a major crop for the Romans. Cultural exchange begotten by cultural exchange.

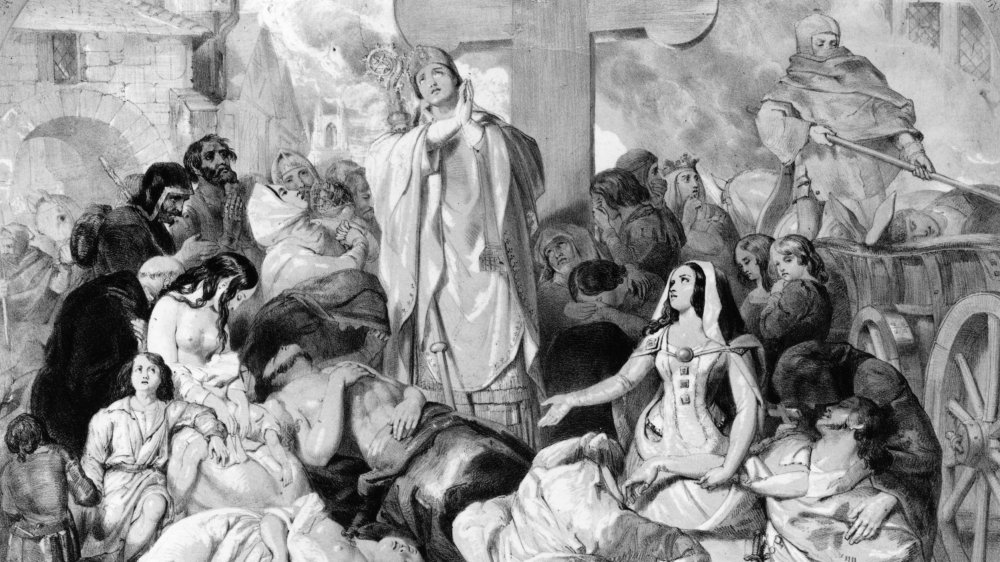

The Silk Road helped spread the plague

Unfortunately, not everything that traveled across the Silk Road was intentional. According to Science Magazine, trade from the Silk Road most likely introduced the bubonic plague into Europe in 1346 A.D., which led to the death of almost half of all Europeans within seven years.

The most often cited theory of how the plague got to Europe is through infected rodents, who traveled with infected travelers and merchants. However, it's likely that plague-infected fleas on travelers' horses and camels played a prominent role as well. According to Asia Society, it's also possible that marmot pelts had been contaminated with flea eggs that were plague-infected, hatching into fleas and transmitting the infection into port cities in the Middle East and Italy.

While no one knows for sure how the Black Death made its way to Europe, the origins of the Yersinia pestis bacteria can be traced to Central Asia. With its historical timing and geographic origins, the Black Death can also be attributed to the Mongol Empire's reestablishment of the Silk Road.

Astronomical ideas

Most knowledge on the Silk Road was an amalgamation of various cultural ideas and influences. Sciences like astronomy were no exception. According to UNESCO, Central Asia was especially influenced by the astronomy of the Greeks and Indians.

It was particularly thanks to Ancient Iranian scholars, who translated Greek astronomy texts such as the works of Ptolemy, that information was able to proliferate through the Arabic-speaking regions. Indian astronomy was also influential to its development in the Muslim world. When Baghdad became a center of scientific learning in the 8th century A.D., scholars from the Indian subcontinent traveled there to spread and expand their own knowledge.

Some places like Dunhuang, China, assimilated Arabic and Indian astronomy into their own Chinese calendars to create a mixture of lunar and solar calendars. Samarkand, Uzbekistan was also an intellectual center and the location of a short-lived astronomy center, where astronomer Ulugh Beg and other scholars created tables denoting the movement of the heavens and predicting eclipses. Through the Silk Road, knowledge was able to be shared and expanded upon as different regions developed various instruments and techniques for understanding the universe.

The most delicate commodity on the Silk Road

The amount of glass that was shipped from west to east was so vast that the Silk Road could've been easily called the Glass Routes. First produced around Mesopotamia and Egypt, the earliest archaeological records of glass date back to 3500 B.C. When Syrian craftsmen invented the blowpipe in the 1st century B.C, this revolutionized the glassmaking process. Before the blowpipe, glassware was made by pouring liquid sand into molds. The new technique led to cheaper and easier production and improved upon glass' quality and delicacy.

In China, ceramic and porcelain objects made of faience and frit were significantly more common before the proliferation of glassware. According to UNESCO, imports of glassware to China can be dated back to the late Spring and Autumn period (771-403 B.C.) But while glassware started being produced more commonly during the Warring States Period (475-221 B.C.) and the Han Dynasties (206 B.C.-220 A.D), the focus on ceramics and porcelain slowed the development of glass-making technologies.

Glass-making technologies also developed in India as early as 1730 B.C. and according to the Australian National University, they traded their glassware with the Vietnamese Sa Huỳnh culture. The proliferation of glassware demonstrates the extent to which various regions and cultures interacted with one another. Glass beads have been excavated across South East Asia, and in South China, they have been found in the tombs of nobles and common folk alike. Glassware of possible Roman origin has also been found as far as the Korean Peninsula.

Leave a paper trail

Before the Chinese invention of paper, papyrus and parchment were used across Europe and central Asia. While parchment was more durable than papyrus, it was typically more expensive since it was made out of an animal's hide. According to Ancient History Encyclopedia, Cai Lun is credited with inventing paper in 105 A.D, using soaked plant fibers that he pressed and dried into sheets. The technique continued to be refined and experimented with as the centuries passed, trying to create the best quality out of the cheapest mix, and with the invention of block printing in the 8th century A.D., the usage of paper soared.

While paper soon began traveling down the Silk Road, the method of paper production took some time to follow. As a result, many towns such as Turfan and Samarkand reused the Chinese paper for government documents and contracts due to the paper's durability.

By the 7th and 8th centuries, the method of production started making its way across Eurasia. Introduced initially to Korea, who then brought the technique to Japan, paper-making also made its way to India by 650 A.D. The method soon took hold in the Islamic world as well as the Islamic caliphate used paper production to quickly develop their own paper. By the 10th century, Buddhists, Muslims, Jews, and Christians were all using paper. The spread of paper and the spread of the method of papermaking was especially crucial to the spread of religious ideologies across the Silk Road.