The Incredible Story Of The 1893 World's Fair

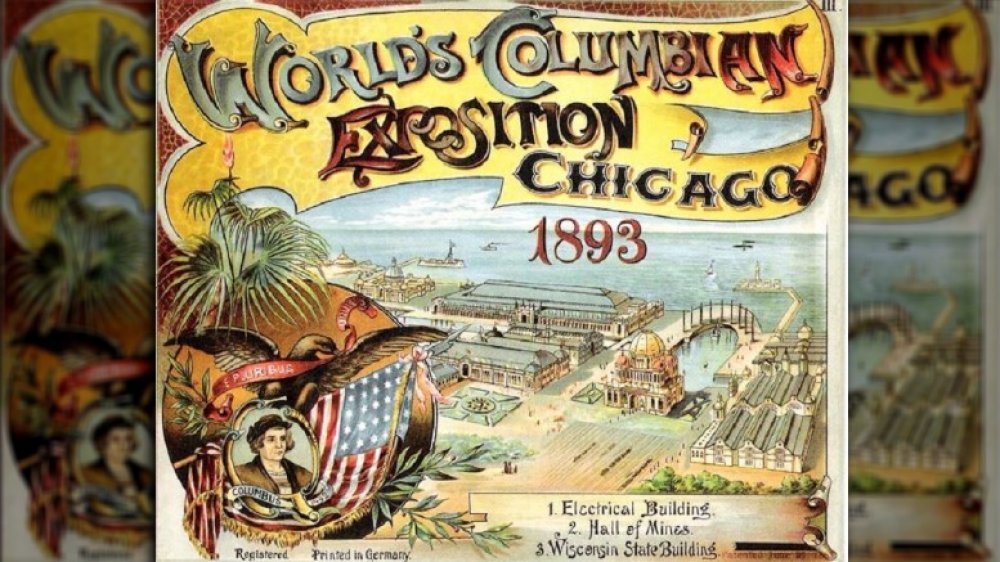

Before the internet, the best way to showcase technology, art, and innovation while uniting different countries was at world's fairs. One of the most famous took place in Chicago in 1893. Honoring the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus' arrival in what came to be called America (albeit a year too late), it was known as the World's Columbian Exposition. It drew an estimated 27 million people, and was four times bigger than the 1889 Paris World's Fair.

The event was a victory for Chicago, which had been ravaged by a terrible fire two decades earlier. But there was a more sinister side. Just 30 years after slavery was abolished, African Americans were excluded from showcasing their achievements, and Indigenous people were gawked at in zoo-like exhibits. Another fire caused the worst firefighting disaster the city had seen to that point — and the Fair would become forever linked with one of America's most notorious serial killers. This is the incredible story of the 1893 World's Fair.

The 1893 World's Fair was a comeback for Chicago

The 1893 World's Fair was considered a remarkable achievement — not least because it took place just 22 years after Chicago was gutted by fire. Between October 8 and 10, 1871, a huge inferno ripped through the mostly wooden city. National Geographic reports an estimated 300 people were killed and 17,500 structures were destroyed. The cost of the damage was around $200 million. With 90,000 of the city's 324,000 residents now homeless, looting broke out. According to History, martial law was declared on October 11 and lasted several weeks.

However, Chicago's leaders — including newly-elected mayor Joseph Medill — saw an opportunity to rebuild a bigger, better, more fireproof city. Fortunately, the railroads and meat plants — Chicago's main industry — were still intact. New laws required buildings be made of fireproof materials, although it took another, smaller fire in 1874 to convince architects and builders to take these measures seriously, according to National Geographic.

In 1890, Chicago beat rivals New York, Washington D.C., and St. Louis in the contest to host the 1893 World's Fair. The city ultimately raised more money than its rivals, from wealthy investors including Marshall Field, the city and state, and ordinary citizens.

The 1893 World's Fair was designed around waterways

The organizers' first priority was designing and constructing the landscape the Fair would take place on. For this, they hired America's most famous landscape artist, Frederick Law Olmsted, and his business partner Harry Codman, who sadly died before he could see their plans come to fruition. The pair organized their design around a series of artificial lagoons and waterways, complete with artificial islands. One of the main attractions was the Basin, a huge pond in the Court of Honor which featured the 65-foot gold-gilded Statue of the Republic: a robed woman holding a globe and a staff.

Guests could travel between exhibits by traditional Venetian-style gondolas or on newfangled electric-powered boats. Several boats also served as attractions in their own right. The Viking was a traditional Viking ship that was built in Norway and sailed across the Atlantic to New York, then on to Chicago. It's currently on display in Geneva Park, IL. PBS reports that there was also a Japanese dragon boat and replicas of Columbus' three ships.

Olmsted took special pride in the Fair's gardens, according to the Chicago Tribune, and one country in particular benefited from his obsession. The Japanese Pavilion stood on the Wooded Island, looking out on a small garden known as the Japanese or Osaka Garden, complete with cherry trees.

The 1893 World's Fair was an architectural triumph (if you didn't look too closely)

The Fair's organizers appointed legendary Chicago architect Daniel Burnham as chief of construction, and he assembled the Avengers of 19th century American architects.

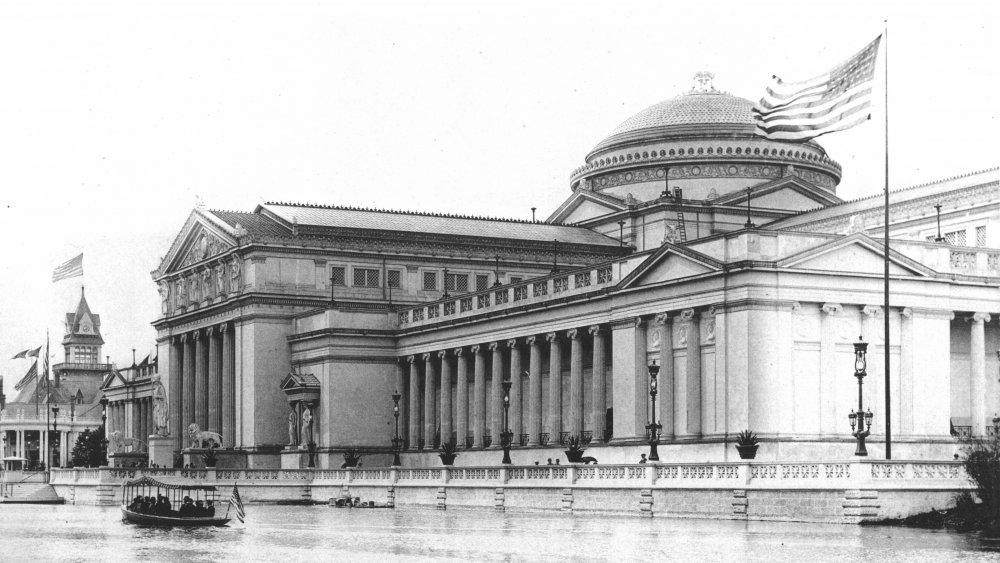

Ironically for a fair that was supposed to celebrate American achievements, they agreed on the European Neoclassical style for the Exposition's main focal point: the Court of Honor. This was made up of enormous halls that hosted the exhibitions deemed the most exemplary. (Not coincidentally, also the ones made exclusively by men of white European ancestry.) These included the Machinery Hall, the Agricultural Building, and the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building. All the buildings were painted white — hence they were collectively dubbed the White City. The exception was the Transportation Building at the eastern end of the Court of Honor, which was painted in bright colors and gilded in gold.

As beautiful as the buildings were, they were only designed to be temporary. Most were made from a mixture of plaster, cement, and a type of fiber called staff. But even after the Fair had been dismantled, the legacy of the White City continued. PBS reports that it led to a renewed interest in Neoclassical architecture, and it may have influenced the creation of another, equally imaginative place. According to the Chicago Tribune, the dazzling achievements of the White City potentially inspired Wizard of Oz author and Chicago resident L. Frank Baum to create the Emerald City.

The 1893 World's Fair introduced many Americans to electricity

The 1889 Paris World's Fair had shown off electric lighting, but the 1893 Exposition took the electrical revolution to the next level. Most Americans had still never encountered this seemingly magical technology before, and they got a dramatic introduction. At the Fair's opening on May 1, President Grover Cleveland pushed a button and the electrical power turned on. Hundreds of thousands of lights illuminated the buildings of the White City.

It was the first World's Fair lit solely by electricity, but the spectacle went even further than that. A whole exhibition hall was dedicated to electricity. Guests could witness innovations such as electric sewing machines, irons, laundry machines, an early fax machine, and — more macabre — electric chairs. There was also the world's first "moving sidewalk" — the predecessor of the ones used in airports today.

All this electricity was provided by one of history nerds' favorite inventors. Yes, the 1893 Exposition is part of Nikola Tesla's unbelievable real-life story. According to PBS, Tesla sold his patents for an electrical system based on AC current to George Westinghouse. Westinghouse used them to undercut rival Thomas Edison's General Electric Company and win the bid to supply electricity to the Exposition. But Edison still had a presence at the Fair: it was the first time many visitors ever saw a light bulb, and he showed off his Kinetoscope, an early device showing moving pictures.

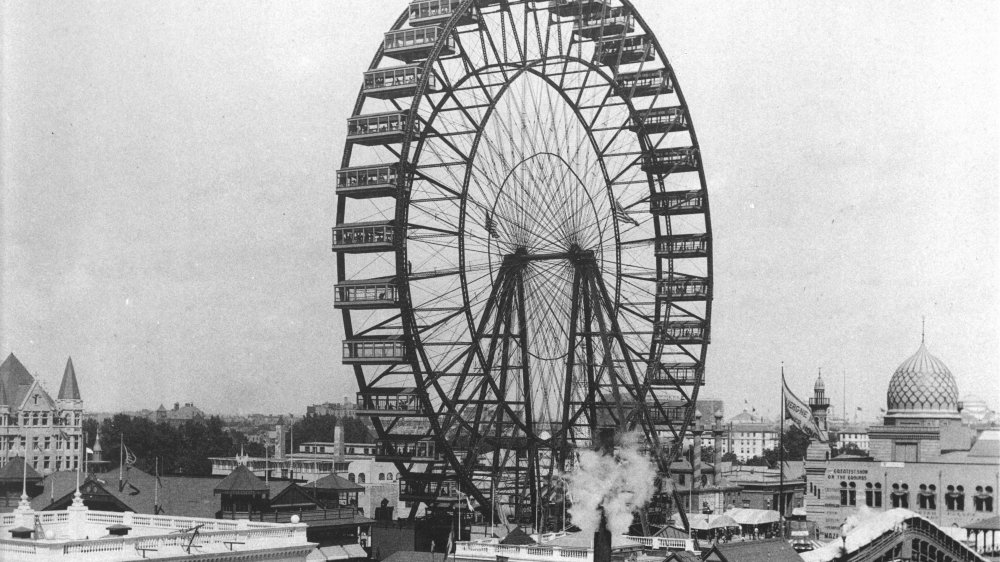

The 1893 World's Fair introduced the world's first Ferris wheel

Although world's fairs were supposed to unite people from different countries, they were also opportunities to show off what your city and country was capable of. Kind of like the Olympics. Chief of construction Daniel Burnham was especially keen to outdo the 1889 Paris World's Fair, which had unveiled one of the most iconic structures of all time: the Eiffel Tower.

He got his answer from a structural engineer named George Washington Gale Ferris, Jr. Ferris' original job at the Fair was inspecting steel, but after learning that Burnham was looking for a centerpiece, he presented his idea for an enormous wheel, spinning on a central axle. This was no carnival attraction: according to the Chicago Architecture Center, it was 264 ft tall, with 36 gondolas that could each hold 60 people, for a total of 2,160 riders at a time. Burnham was skeptical, and Ferris spent his own money running safety tests. Eventually he succeeded in convincing Burnham, and the Ferris Wheel became one of the Exposition's main attractions: approximately 1.4 million visitors paid the 50-cent fee.

However, after the Fair, the wheel failed to find a permanent home. After a stint in Chicago, it was sold and reassembled for the 1904 World's Fair in St. Louis. But two years later, it was destroyed for scrap metal. However, according to the Chicago Tribune, local divers claim to have found remnants in Lake Michigan.

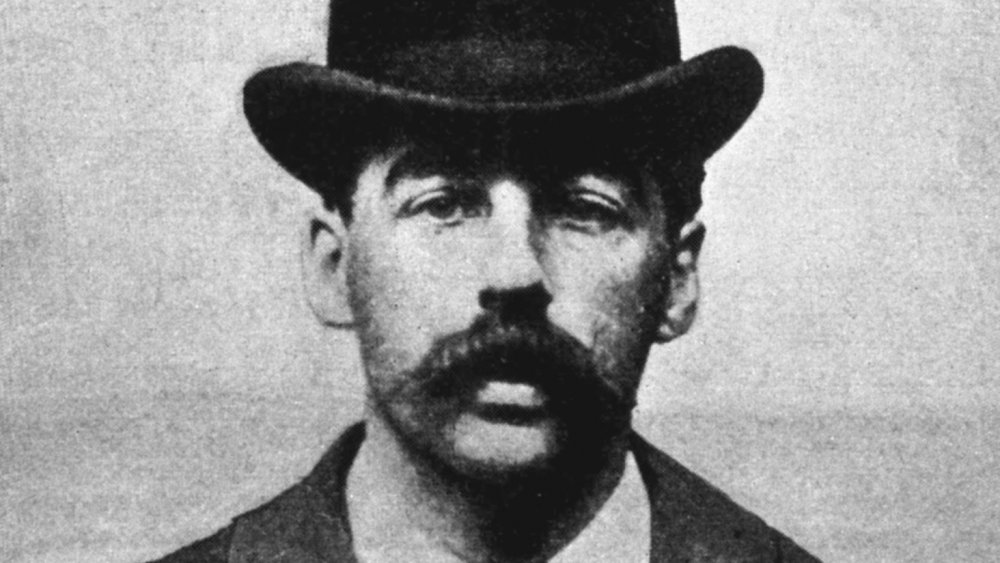

A serial killer was at work during the 1893 World's Fair

The 1893 World's Fair was the backdrop for one of America's most notorious serial killers. H. H. Holmes came to Chicago around 1885 and started working in a pharmacy in Englewood, eventually taking it over. He had a building constructed nearby, on 63rd Street, which he ran as a hotel during the Fair. Later dubbed the Murder Castle, Harper's reported in 1943 that it contained secret passageways, staircases that lead nowhere, rooms with no doors, gas fixtures that lead into bedrooms, and a kiln in the basement. Guests and employees got lost in the dark maze, and Holmes would torture them, kill them, and dismember or burn their bodies in the basement.

Many historians now believe that stories about Holmes and the Murder Castle were exaggerated by the press at the time until they became myth. That said, there's strong evidence that Holmes did murder multiple people, including children, as part of his many insurance scams. Estimates range from nine to 200 and at one point he confessed to 27, but some of those supposed victims were still alive (awkward...).

According to Harper's, Holmes was caught in November 1894 after murdering a long-time associate to claim the insurance. He was hung in Philadelphia in 1896 for that murder, although a conspiracy theory that he escaped led to his body being exhumed in 2017. Rolling Stone reported that tests confirmed it was indeed Holmes.

The 1893 World's Fair was devastated by two fires

You'd think the Great Fire of 1871 would have made Chicago cautious about fire safety. But the World's Fair experienced two destructive blazes.

On July 10, 1893, two months into the Fair, a fire broke out in the smokestack of the cold storage unit, used for food. Firefighters were trapped above what the Chicago Tribune referred to as "a pit of fire." Eventually the tower collapsed, killing everyone left inside. A total of 16 people died, including 12 firefighters, making it the deadliest incident in Chicago firefighting history to that point. An investigation found that faulty wiring had been discovered in January, and a smaller fire had broken out just a month before. Four people were charged with criminal negligence, including chief of construction Daniel Burnham, but they were all acquitted by a grand jury.

The second fire was less deadly but more destructive. After the Fair ended, Chicago leaders were left to decide what to do with the White City. But on January 8, 1894, the decision was made for them by a huge blaze. A Chicago Tribune article published the following day reported that the fire started in the Casino, destroyed the Peristyle (a grand gate) and the Music Hall, and damaged most of the other buildings in the Court of Honor. Two people were killed and two more wounded. The crowds who gathered to watch the flames wept as they witnessed the White City burn to ruins.

The 1893 World's Fair introduced some popular food brands

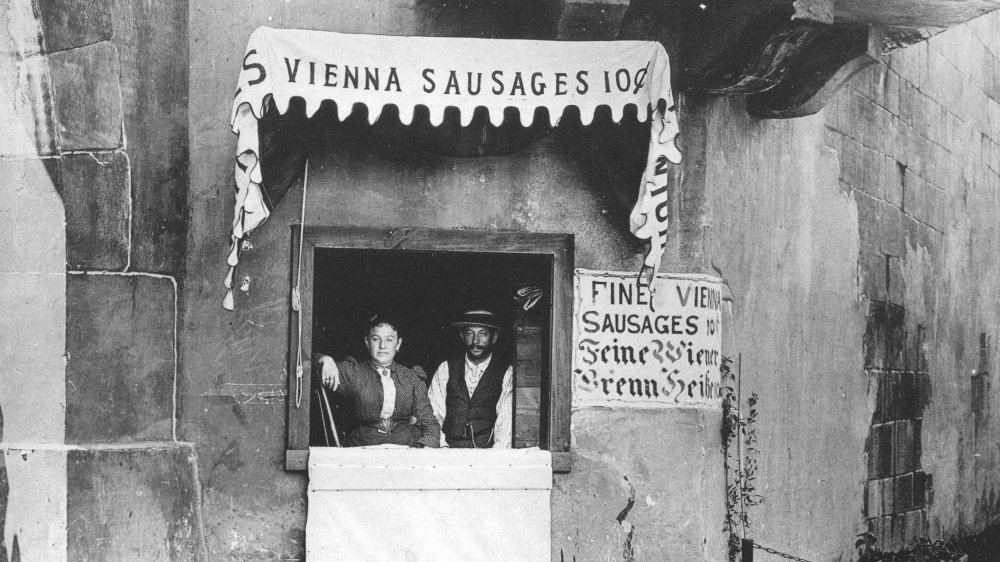

World's fairs showed off the latest innovations from around the globe in a variety of industries. And some famous products today tie their histories to the 1893 World's Fair — correctly or not.

A common story has Cracker Jack being introduced at the Fair, by German brothers Frederick William and Louis Rueckheim. But according to NPR, it's possible that the popular 1908 song "Take Me Out to the Ballgame," which name-drops the brand, was actually responsible for its success. Similarly, Pabst Blue Ribbon did not win its titular prize at the 1893 World's Fair, although the brewery did take home the award for best beer.

Another product supposedly introduced at the Fair was Wrigley's Juicy Fruit chewing gum. William Wrigley created the flavor in 1893, and he had a concession stand at the Fair, so it's possible. Meanwhile, Austrian-Hungarian brothers-in-law Emil Reichel and Samuel Ladany had such success selling their Vienna sausages that they started the Vienna Sausage Company, which still dominates hot dog stands today.

You can also blame the 1893 World's Fair for one of the most controversial mascots in history. NPR reports that businessman R.T. Davis used the Fair to introduce Aunt Jemima, played by Nancy Green, to sell his pre-made pancake mix. Green played the stereotypical Southern Mammy character to enormous crowds during cooking demonstrations (and no, she didn't become a millionaire, according to the Associated Press.)

African Americans were excluded from the 1893 World's Fair

African American leaders had hoped to use the 1893 World's Fair to show what Black people had achieved in just three decades since the Emancipation Proclamation began the end of slavery. But while all 44 states (at the time) were represented, along with many other countries, the organizers refused to let African Americans exhibit as a collective group. They were also excluded from organizing committees and the opening ceremony, and Black women were rejected from participating in the Women's Building.

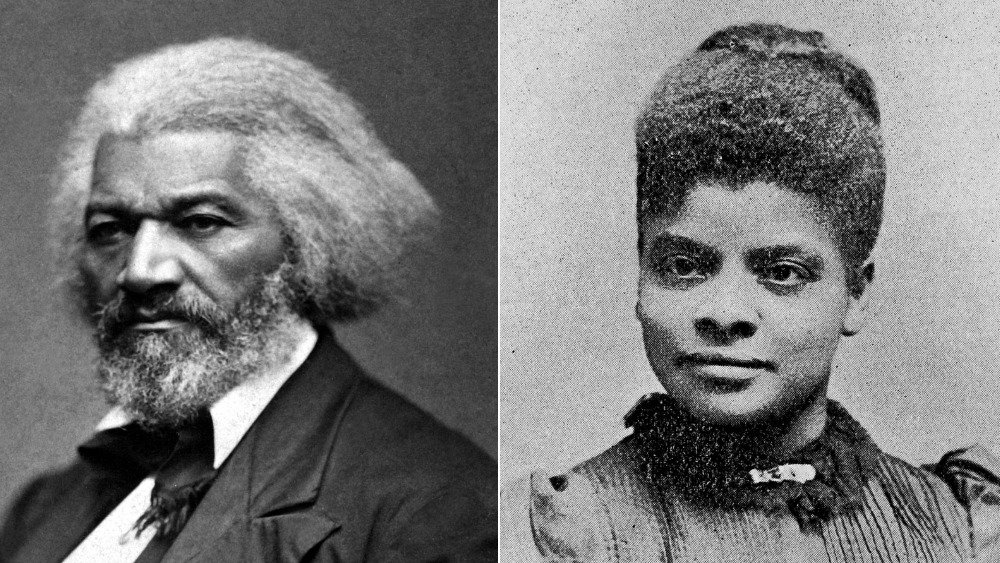

But some Black leaders still found ways to make their voices heard — literally. If you know the crazy real-life story of Frederick Douglass, you know he wasn't easily deterred. Douglass was invited to represent Haiti at the Fair, and he used the opportunity to make a speech condemning American racism during the Fair's dedication ceremony. When the Fair opened, he and fellow civil rights legend Ida B. Wells and two other activists wrote and handed out a pamphlet on the same theme.

The organizers made one capitulation: they deemed August 25 a day for celebrating African American achievements. Douglass was set to give another speech: but when someone in the crowd heckled him about "the Negro problem," he tossed his notes and delivered a blistering on-the-spot rebuke. In 2009, the Chicago Tribune reported that a plaque commemorating Douglass' contributions to the Fair had been placed on the spot where the Haitian Pavilion had stood.

Indigenous people endured racism at the 1893 World's Fair

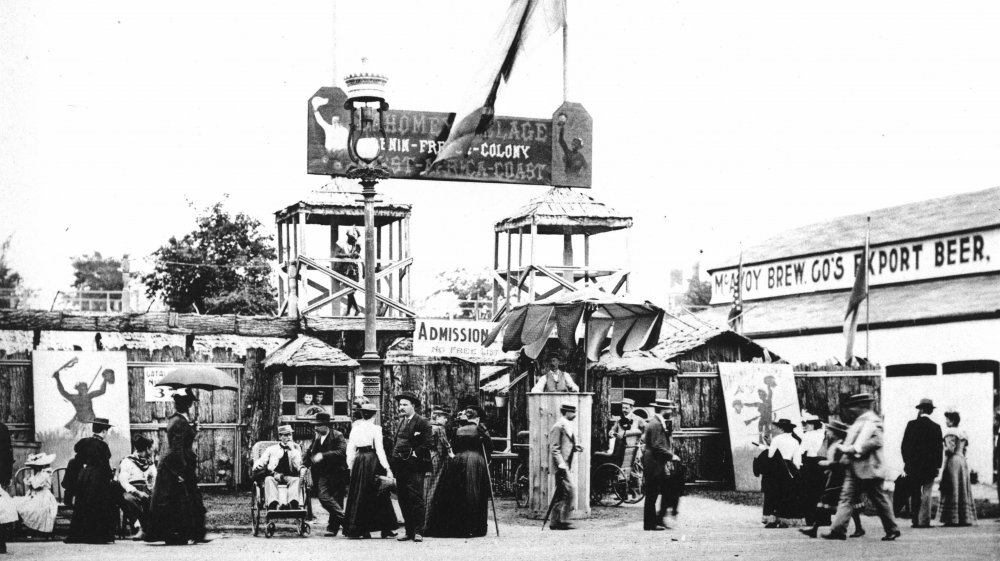

Although African Americans were not allowed to represent themselves, Black and Indigenous people from other countries had their own exhibits. But in some ways, these may have been worse than having no representation. The exhibits were excluded from the grand Court of Honor, which was reserved for what were seen as "developed" nations. Instead, they were housed on the Midway Plaisance, the entertainment strip.

That's housed in the literal sense. The Exposition became a temporary home for people representing some Native American tribes, and for people from Dahomey in West Africa (now Benin). The idea was that visitors could watch them "cook, make trinkets, perform their songs and dances, and go about the ordinary routine of life in their tribes," as page 54 of the official guide to the fair put it. They were treated more like animals in a zoo. According to PBS, Emma Sickles, a staff member at the exhibit, was fired for speaking out against the Fair's mistreatment of Native Americans.

The literature and media that came out of the Fair endorsed this twisted perspective through racist cartoons and descriptions. They also associated African Americans with what they saw as the primitive Dahomeans — something Frederick Douglass condemned in his speeches and pamphlet.

People went to extreme lengths to preserve some of the buildings

The buildings that made up the Court of Honor were designed to be temporary: but some of the structures on display inside were saved for other uses.

Renowned brewer Captain Frederick Pabst (yes, those Pabsts) brought a beautiful green-domed pavilion complete with terracotta statues of gods and goddesses to Chicago to represent his brewery. And he took it back with him after the Fair, attaching it as an extremely fancy extension to his already extremely fancy mansion in Milwaukee, WI. Since 1978, the mansion has been used as a museum, with the pavilion serving as the entrance and gift shop, although it has suffered extensive damage in the harsh winters.

Another structure traveled even further. The Norway Building was constructed in Orkdal, Norway, and then moved to Chicago and rebuilt for the Fair. After the Fair, it was moved to Geneva, WI, to a businessman's estate. After his death, the estate's new owner painted it yellow and used it as a theater. In 1935, it was moved to Madison, WI, to be part of the Norwegian-American museum called Little Norway. But in 2014, the grandson of one of the craftsmen who constructed the building in 1893 campaigned for it to be brought back to Norway and restored. In 2017, after years of planning and restoration work, it was reopened in Orkdal, Norway, where the Wisconsin State Journal reports that it's still used for weddings, lectures, and meetings.

Two of the 1893 World's Fairs' most impressive buildings are still in use

Fortunately, not all of the buildings were torn down or destroyed by fire. According to the Chicago Tribune, the Palace of Fine Arts was built specifically to be fireproof. It was used to display works of art from all around the world during the Fair, and the lenders were understandably nervous about their precious pieces disintegrating in flames, given Chicago's less-than-hot record on huge fires.

After the Fair, the building became the Field Museum, housing natural history artifacts. In 1921, the museum moved to its current location on Lake Shore Drive. The building stood empty until a restoration project starting in 1926 prepared it to become the Museum of Science and Industry, just in time for Chicago's next World's Fair, the 1933-34 Century of Progress. It's still there: the current entrance was the back during the Fair.

The other building may be more familiar: it's one of the things in Ferris Bueller's Day Off you only notice as an adult. While most of the World's Fair took place on the South Side of Chicago in Jackson Park, the World's Congress Building was downtown. It hosted the World's Congress Auxiliary, a series of meetings on the social topics of the day. Afterwards, it was taken over by the Art Institute of Chicago, which had partly funded its construction. We can't visit the 1893 World's Fair, but we can retread the visitors' footsteps in these beautiful buildings.