What Your History Class Didn't Teach You About Auschwitz

Auschwitz. There are few places on earth that conjure up more images of death, horror, and pure agony than the Nazi's most infamous concentration camp. We learn that it was a place where the so-called "undesirables" were sent — usually to die. But it was worse than you ever learned in high school, because there are some places history classes just won't go.

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, around 1.3 million people were sent to Auschwitz between 1940 and 1945. (To put that in perspective, that's about the same as the entire population of Maine.) In those five years, 1.1 million of those people were murdered there.

The very first prisoners arrived on June 14, 1940. DW says those original 728 prisoners were Polish resistance, and that was the initial purpose of the camp: to house those deemed most dangerous to Nazi rule. Most were students and scholars, and they were under the cruel, watchful eyes of 30 German criminals the SS appointed as guards. It wasn't long before Auschwitz became the final destination for many, many more. Here's what no one ever told you about the Nazi's most infamous camp.

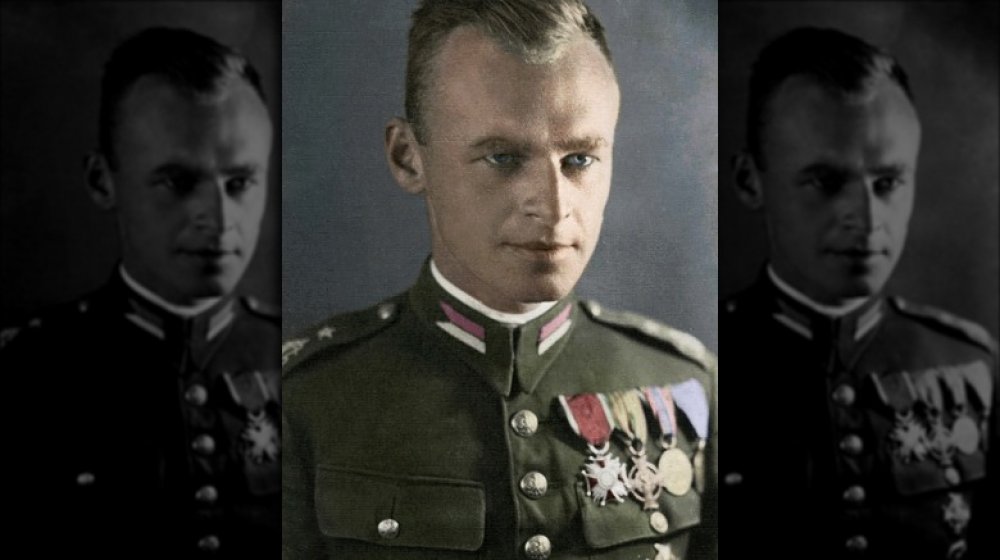

The man who volunteered to go to Auschwitz

On September 18, 1940, a Polish cavalry officer named Witold Pilecki walked into a crowd of people in Warsaw. They were being rounded up by German officers in preparation for a trip to Auschwitz, and he went: voluntarily, says The Washington Post.

According to The New York Times, he smuggled out a series of reports on what was really going on inside the camp. Documents made their way out in 1940, 1941, and 1942, and after his escape — which happened in 1943 — he wrote more. The result is an eyewitness account of the horrors, starting with the very public executions of some of the camp's Polish prisoners, who were sometimes shot, and sometimes, they were left to the elements. Later, he saw the focus shift to Jewish prisoners, writing: "Over a thousand a day from the new transports were gassed. The corpses were burnt in the new crematoria." And all the while — while fighting typhus and suffering beatings — he organized a resistance network within the camp, in addition to sending messages. (The first message? "Bomb Auschwitz.")

Pilecki escaped in 1943, and he did see the end of the war and the liberation of the camp. But his loyalty to the idea of a free and independent Poland was seen as problematic: he was arrested in 1947, tortured, declared an enemy of the state, and executed the following year.

When you have nothing left to lose... why not?

Also targeted by the Nazis for extermination? The Roma. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, around 23,000 Roma were sent to the camp, and 21,000 died there. But they were also part of an insanely brave rebellion.

Most were held in a section of Auschwitz called Zigeunerlager, which was a sort of holding center for entire families. It was established in 1942, then in 1944, it was decided that everyone in the camp was going to be executed, for the simple reason that the space was needed for more prisoners. At the time, there were around 6,000 Roma living there, and on the day after they were warned that their executions were in the pipeline, about 600 armed themselves with hammers and shovels, barricaded themselves in their barracks, and told the Nazis that if they wanted to take them to the gas chambers, well, they'd better come in and get them.

The date was May 16, 1944, and here's the incredible thing: according to the Council of Europe Portal, they sort of won... at least, temporarily. No one died that day, as had been planned. Instead, half of the Roma prisoners were transferred to other camps. For the remaining half, the respite proved to be just a stay of execution. They were sent to the gas chambers on August 2, but still, that day is known as Romani Resistance Day.

Work will absolutely not set you free at Auschwitz

The Sonderkommando were selected from among the healthiest men who were sent to Auschwitz. The Jewish Virtual Library says that some were promised their own survival, and some were told they could protect their families by working for the Nazis. It was rarely the truth and they discovered that very quickly.

Only the healthy and strong were selected for the Sonderkommando because they had to be able to lift a corpse: part of their job wasn't just to lie to prisoners as they escorted them to the gas chambers, but to remove the bodies afterwards... and given that their families usually came with them on the same transport, for many, the first job involved the disposal of family members. They would sort through clothes, collect valuables, extract any gold teeth, and carry the bodies to the crematoriums... then, when the ashes of the bodies started to pile up, they were the ones that disposed of the ash in a nearby river.

They were tasked with helping the Nazis and hiding evidence, but not all were completely compliant. In 1944, several Sonderkommando smuggled in a camera and took pictures of women waiting in line to die in the gas chambers, and of bodies being burned. Another — Marcel Nadjary — documented what he saw, and buried his diary in the forest outside Auschwitz, where it was discovered in 1980.

History says that only around 100 Sonderkommando survived the Holocaust.

Let's take some of 'em with us

The Jewish Virtual Library says that every few months, the Sonderkommando of Auschwitz would be executed, and new prisoners were selected to take their place. By the time this had happened a few times, people knew what they were in for... and the 12th Sonderkommando decided they were going to take some Nazis with them.

The revolt happened on October 7, 1944, but the seeds were planted much earlier with help from Roza Robota and sisters Ester and Hana Wajcblum. They worked at the munitions factory where they — along with co-conspirators Regina Safirsztain and Ala Gertner — started smuggling out gunpowder. Getting it to the Sonderkommando wasn't terribly difficult: since part of their job was moving bodies, they'd sometimes stash the gunpowder on the corpses heading for disposal.

They had plans for the gunpowder, but the revolt first started in Crematorium 1, when Polish prisoners grabbed a particularly sadistic guard and stuffed him in an oven. The workers at the other three crematoriums soon join in, and all that gunpowder? That was taken to Crematorium 4, which the Sonderkommando there detonated in a suicide mission — that crematorium would never be used again.

The rebellion was squashed, and 200 Sonderkommando were immediately executed; their bodies were disposed of by the 13th Sonderkommando. The women involved were discovered and tortured, but never gave up names of living conspirators. They were hanged on January 5, 1945.

The twin experiments of the Angel of Death

Whenever new prisoners would come into Auschwitz, Dr. Josef Mengele and his assistants would be posted up at the entrance, waiting and watching. Among the things they were looking for? Twins. According to the BBC, there are records that suggest Mengele experimented on 732 pairs of twins at Auschwitz (although other estimates place the number at around 1,500). Some survived (like those pictured), and many gave testimony later as to what was done to them... and it's pretty horrible.

History says that often, one twin would be used as a control subject, while the other was the subject of experimentation. When the twin who was being experimented on died, the other was killed and they were both autopsied, in the hopes they could unlock new knowledge about nature vs. nurture and genetics.

What kind of experiments? There were some that remembered being given injections that were supposed to change a person's eye color, while others were deliberately infected with various diseases and substances selected for the severe reactions they would cause. Twins would be measured and documented, their reactions — sometimes to things like surgery without anesthetic, and forced sterilizations — would be recorded, all with one goal in mind: to find new ways to advance the development of Hitler's Aryan master race (via The New York Times).

Block 10

Located in the Main Camp of Auschwitz was an area called Block 10, and even though the only doctor you may have heard about was Josef Mengele, he wasn't the only one performing medical experiments there. Carl Clauberg was working in Block 10, too, and he was interested in finding a way to easily sterilize large groups of people. Among his experimental methods was a non-surgical procedure that introduced chemical irritants into the female reproductive organs. The inflammation it triggered caused swelling and sterilization, and according to the Jewish Virtual Library, it also caused quite a bit of death. Dr. Horst Schumann was working on the same project, only his methods involved exposing patients to X-rays, in order to try to find just the right amount of radiation to sterilize without burning. (This was deemed "unsatisfactory," as there were too many casualties.)

Also there? Dr. Johann Paul Kremer, who was starving prisoners to see just what happened as people wasted away, and questioned them on their deathbeds. Doctors Entress, Vetter, and Wirths were a part of clinical trials financed by IG Farben — manufacturers of Bayer — that studied how well new drugs did in combating disease... most of which was given to prisoners on purpose.

And Dr. August Hirt took the opportunity to collect a whole bunch of Jewish skeletons, in the hopes of taking measurements that would confirm Jewish individuals were biologically different and therefore, inferior to Hitler's master race.

Block 11

Being sent to Auschwitz might seem like enough punishment, but there was an entire block just dedicated to more punishments: Block 11. Most of its punishments were reserved for prisoners who were suspected of things like sabotage or escape attempts, and those who were caught trying to break out? The Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum says those prisoners were usually condemned to death by starvation, and were kept in the dark cells.

Along with the aptly-named dark cells, there were also regular cells, and standing cells. Those had floor space of less than a square meter, air that entered through a single vent that was just five centimetres square, and some were sent there for weeks at a time — usually just at night, though, as they were required to work as usual during the day.

It wasn't just for those who had been sent to Auschwitz, either — the Jewish Virtual Library says that anyone living outside the camp who was caught helping prisoners could end up there, too, along with prisoners of war. This was also where Zyklon B was trialed: between September 3 and 5, 1941, 850 Soviet and Polish prisoners were killed in the basement.

And outside? There — between Block 10 and 11 — was the Death Wall (pictured). Floggings were done in the courtyard, and executions were done against the wall.

The man who saved the children of Auschwitz

Fredy Hirsch could have escaped: according to Holocaust.cz, his mother, brother, and stepfather headed to Bolivia after Hitler's rise to power. He stayed, though, and in doing so, saved countless children. At first, he worked with the children in the Jewish ghettos: he made sure they had personal hygiene items, and that they continued their education and got daily exercise. In 1943, he was caught facilitating communication between Jewish children in Terezin and the outside world: he was sent to Auschwitz, but he continued caring for the Nazis' youngest victims.

Once in Auschwitz, he established the children's blocks, where kids would spend their days before returning to their parents in the barracks at night. There, he oversaw their continuing education (which was done in secret), and arranged for life-saving concessions. Because of Hirsch, roll-call was done indoors instead of outside in the rain and snow, and he also secured a steady supply of extra food: packages that came into the camp addressed to people who were already dead were redirected to the children.

By the beginning of 1944, there were hundreds of children attending his day camp. Until, that is, he was approached by Auschwitz's underground resistance and asked to join. The resistance gave him an hour to decide: when the hour was up, his body was discovered. No one is sure what happened to him, but he did appoint two successors to make sure his work protecting the children of Auschwitz continued.

The 144

144. Out of the 1.3 million people sent to Auschwitz, that's the number who escaped and survived: 144. The first was a Polish prisoner named Tadeusz Wiejowski. He was one of the original group of prisoners to be taken to Auschwitz on June 14, 1940, and he was prisoner number 220. When a group of civilian electricians went to do work at the camp, it was his opportunity: he donned work clothes, and simply walked out.

Punishment was harsh, says the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. The remaining prisoners were lined up outside, where they stood for 20 hours as SS guards walked back and forth, kicking and beating prisoners at their whim. One man — Dawid Wongczewski — died, and became the first of Auschwitz's victims. Those who the SS believed had helped during the escape were publicly flogged.

Going forward, escapes were few and far between. Some stole SS uniforms and cars and left in plain view of others, and in 1942, one group of Polish prisoners who did exactly that also carried a report written by Witold Pilecki. Others had help from underground resistance movements and some were successful, but more often than not, failed escape attempts resulted in interrogation and execution.

The brothels of Auschwitz

It's well-known that those who were imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps and were healthy enough to work were forced to do so, but it wasn't until fairly recently that another part of the Nazi's forced labor scheme came to light: Heinrich Himmler's reward plan. According to The Local, it was Himmler who decided female prisoners could be turned into sex workers, and there were a few things they thought were at play here. For one, Himmler believed he could prevent homosexuality by making women available, and secondly, Reuters says they also thought that workers would work harder if they were promised a trip to the brothel at the end of the day.

DW says that there were 10 brothels at the various camps, with the largest being the one at Auschwitz. There, 21 women worked at the same time — some, it was believed, volunteered, while others were simply escorted there, only to realize where they were when their first "client" was shown in.

The women who have spoken about their time working in a Nazi brothel have talked of the numbness, the shame, and described how they were forced to see as many as 10 men in a span of two hours. Some would take advantage and sometimes the guards would watch, but others, the women remembered fondly. Some, they said, just wanted to talk to a friendly person.

Liberation from Auschwitz wasn't the end for many

On January 27, 1945, the 60th Army of the First Ukrainian Front became the first of the Allied troops to set foot in Auschwitz, and the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum says that around 7,000 prisoners were waiting for them. The sight was a terrible one, but for thousands of others, they were still in hell.

The Nazis knew that the Soviet Army was coming, and in addition to trying to destroy a ton of evidence, they also tried to move around 56,000 prisoners deeper into German territory, where they could still use them as forced laborers. Yes, we know it happened, but according to The New York Times, there was so much chaos and confusion that it's one of the least documented and least understood time of the Holocaust.

We do know that those who were forced to leave Auschwitz on foot ahead of advancing troops were selected: only those thought strong enough to survive were taken. Still, it's estimated that around 15,000 people died along the death marches from Auschwitz alone, says the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Memorials mark the places where groups were executed. Some were shot as they went through villages: when the death march passed, the dead were collected and given a proper burial. For many others, there's nothing.

The debate on whether or not to bomb Auschwitz

Witold Pilecki reported on what he'd seen at Auschwitz, and The Washington Post says that from his first messages to the outside world to his impassioned, post-escape pleas, he wanted Auschwitz to be bombed. Those living there were trapped in hell, he argued, and putting an end to their suffering and the Nazi's mass killings just needed to be done. But Auschwitz was never bombed. Why? It's complicated.

According to The Guardian, Pilecki wasn't alone: representatives of the Jewish community also petitioned the US War Department, asking them to bomb Auschwitz and put an end to everything that was going on there. The US declined, citing a few reasons: they claimed it would require precision bombing they didn't have the capability of carrying out, that it was well beyond the maximum reach of their bombers anyway, air forces were needed elsewhere, and it posed too much of a danger to American troops. According to the Jewish Virtual Library, there was another reason: the guarantee of civilian casualties. The question came up again and again, and in 1944, the answer was still "No."

But what about those who were in the camp? The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum says that some survivors recalled hearing nearby bombs, and remembered the hope it gave them: "We were no longer afraid of death; at any rate, not of that death. Every bomb that exploded filled us with joy."