The Crazy Real-Life Story Of Marco Polo

Why has the name Marco Polo stayed with us after so many centuries? Born into a wealthy Venetian mercantile family in the 13th century, his background was exclusive, perhaps, but not exactly unusual for the time. But to tell his tale, we have to talk about the travels of his relatives before him, as well as the fact that their own journey gave the young Marco Polo a trajectory that would shape the course of his life.

The circumstances into which the world-famous explorer and writer Marco Polo was born were suitably epic. His father, Niccolo, and uncle, Maffeo, were successful travelers and traders who had set off to Asia just after Polo's birth. After setting up a number of trading posts along the Silk Road, their travels brought them to the court of of Kublai Khan, the legendary fifth khagen of the Mongol Empire.

The Polo brothers were well-received at the court of Khan, sharing their knowledge of the Holy Roman Empire and of European Christianity. At the behest of Khan, the brothers were charged with returning to Italy, accompanied by a Mongol ambassador and a letter from Khan himself, to request from the pope 100 representatives to teach Christianity and Western customs in the Mongol Empire. It was this directive which would lead Marco Polo to the life we know him for today.

Marco Polo's early life was mostly parentless

Niccolo and Maffeo had set out on their journey just before Marco was born in 1254 (birthplace pictured), leaving Marco's mother to raise him alone, per History. Tragedy struck, however, when his mother died while Marco was still at an early age, meaning he was raised by extended family. Very little is known of Marco's activities in this early part of his life, apart from the fact that he was already a teenager by the time his father and uncle returned from the court of Kublai Khan.

Niccolo and Maffeo's first meeting with 15-year-old Marco in 1269 occurred in inauspicious circumstances. The pope whom they had been charged with addressing was dead — their mission on behalf of Kublai Khan was scuppered. The brothers had to wait for the naming of a new pope, which was a long, drawn-out process. The two eventually addressed the new pope, Gregory X, in 1271. The pope could only spare two priests to accompany the Polos on their return journey to Kublai Khan but did agree to Khan's request for some lamp oil from the sepulcher at Jerusalem.

And so, planning to collect the lamp oil and priests en route, the Polos began their journey back to Khan — with the young Marco alongside them.

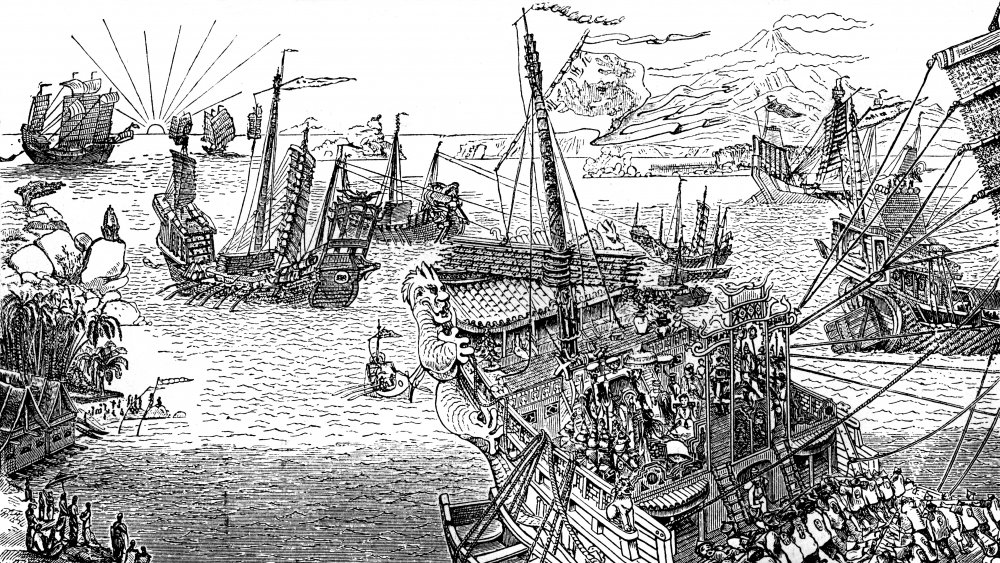

The Polos traveled the Silk Road to Kublai Khan

Travel in the 13th century was unthinkably difficult, but the elder Polos were experienced, tough traders who were familiar with the routes East that were open to them. According to History, the Polos sailed to Acre, now in Israel, and on to Jerusalem to collect the lamp oil for Kublai Khan. The Polos then returned to Acre, where they recruited the two priests for their mission and collected a number of gifts and papal documents to present to their patron upon their arrival in the East.

The arduousness of the route can be gleaned from the fact that the two priests almost instantly abandoned the journey, turning back before the group reached Hormuz, a port city in Persia in which the Polos attempted to secure a seaworthy vessel. However, the sea route proved inaccessible, and as a result, young Marco found himself slowly trekking through the winding mountain trade routes that we know today as the Silk Road.

The difficulty of taking this route cannot be understated, and it really is remarkable that the young Venetian undertook such an arduous journey as a first-timer, even though he was accompanied by his elders. The group was attacked by bandits, and while in Afghanistan, Marco was struck down by a mysterious illness and had to spend months in the mountains recovering before the group could travel on. The Polos eventually found themselves before Kublai Khan ... after nearly four years of travel.

Marco Polo met Kublai Khan at Xanadu

Having eventually passed into the territory of the Mongol Empire, the group made tracks for the palace at Xanadu — now known as Shangdu, China — the summer residence of Kublai Khan. Polo described the palace's opulence in a way that must have enthralled his contemporaries: "There is at this place a very fine marble palace, the rooms of which are all gilt and painted with figures of men and beasts and birds, and with a variety of trees and flowers, all executed with such exquisite art that you regard them with delight and astonishment."

Polo also described Xanadu's "pleasure park" — more often known as Xanadu's "pleasure-dome," after the opening lines of the famous poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge — as a high-walled garden palace replete with exotic animals and lined with gold and silver. His writings describe parties boasting 40,000 guests, with a banqueting hall large enough to seat 6,000. Polo also wrote of Khan's many concubines and the structure of his family.

By his own account, Polo was well-received by Khan, who enjoyed the young Venetian's charm, learning, and skills as a storyteller. Marco Polo was to spend much of his early adulthood at the feet of the great emperor.

Marco Polo's first solo expeditions were at Kublai Khan's bidding

Though his four-year journey to Xanadu represented an epic initiation into the art of travel, it would be over the following years as a servant of Kublai Khan that Marco Polo would come to repeatedly traverse the continent of Asia at his patron's bidding. After he became a trusted courtier to Khan, the Mongol emperor decided to employ the young Polo as an envoy in the governance of his sprawling empire.

Armed with a seal of approval from Khan himself, which ensured safe passage throughout his kingdoms, Marco Polo traveled to lands previously unknown to Europeans, such as Tibet and Burma (now Myanmar), and extensively explored India, according to Biography. During this time, it is also believed that he worked as a city governor and as a tax inspector and was personally promoted by Khan to the Privy Council.

Though Khan had laden Polo with such responsibilities, his role allowed him open access to Asian lands and their cultures that had previously been unknowable to Europeans, and as a result, many of Polo's accounts of his travels during this time became central to the Western understanding of Asia and its people for centuries. Polo ended up serving Kublai Khan for nearly two decades.

Marco Polo returned to Venice and went to war

As the years wore on and Kublai Khan came toward the end of his life, the Polos became anxious as to what their fates would be once their patron was gone. The travelers asked to be released from Khan's service, but the emperor did not want to lose his European servants.

Eventually, after they'd served him for 17 years, Khan agreed to allow the Polos to return to Europe, after completing one final task: accompanying a young Mongolian princess, Kokachin, to her chosen husband in Persia. The Venetians agreed, though the journey there and then home — mainly by sea — was long and perilous, with many hundreds of their caravan of passengers and sailors hired for the trip perishing in wild storms or from disease. According to Biography, a vast amount of the family's wealth was also taken from them in Turkey, meaning they arrived back in Venice in 1295 with merely a quarter of what they'd set out with.

Worse still, they returned to find Venice at war with the Republic of Genoa, a neighboring independent Italian state. As was customary during the period, Polo, as a man of wealth –which had been increased considerably by the gold and gems he'd brought back from the Mongol Empire — financed the arming of a ship to aid in combat, serving in the fighting himself. During the war, Polo was captured by Genoan forces and imprisoned.

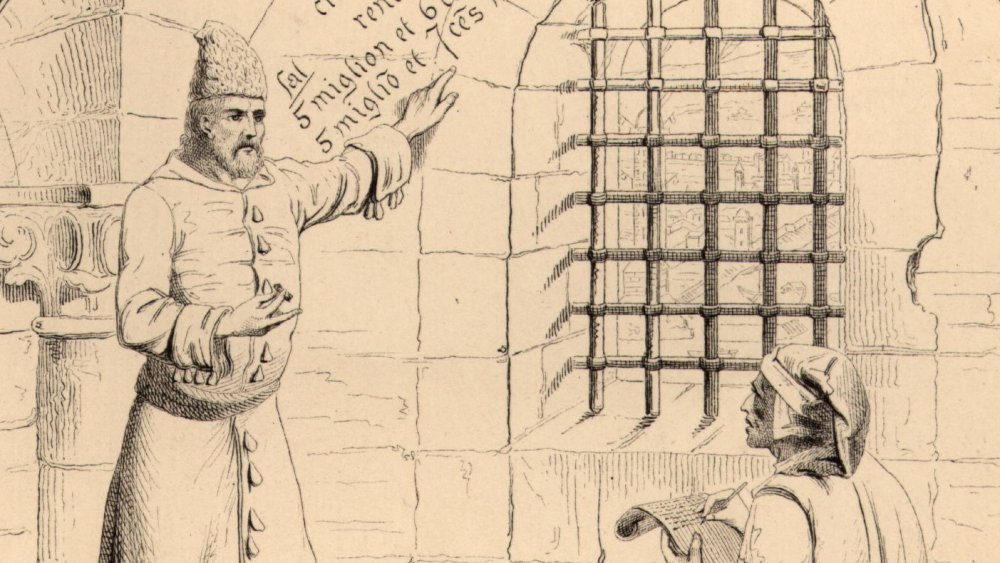

Marco Polo recounted his adventures while in prison

The truth is that if it weren't for his being captured as a prisoner of war, chances are we wouldn't know the name Marco Polo today. While captured, Polo was fortunate enough to share a cell with Rusticello da Pisa, a writer of romances who wrote the first versions of the tales of King Arthur in the Italian language. Polo having shared many stories of his travels with the writer, the two began a collaboration on a book that was to make Marco Polo famous, as detailed by History.

The book, originally titled Description of the World but more commonly known today as The Travels of Marco Polo, is the main source for accounts of the adventurer's life and became a key text upon publication for Europeans seeking insight into a continent and a people that had previously been shrouded in mystery.

To begin with, the book was a manuscript, with fewer than 200 handmade copies in circulation around the western world, according to the Khan Academy. Later, with the advent of the printing press, the story of Marco Polo was to become a bestseller and remained an influence on how Europeans perceived the East for centuries.

Marco Polo brought paper money to Europe

Though Marco Polo's book is a tale of adventure, its importance in bringing new ideas to its European readership shouldn't be underestimated. One example, above all else, shows the cultural impact of Polo's tales upon his readers — that his account was the first to bring them the concept of paper money. It may seem strange to think about it today, but the idea of paper currency was entirely alien to Europe when Polo first sketched it for his readers.

According to the BBC, the paper money that circulated in the empire of Kublai Khan wasn't like the paper we know today — nor is our money actually made of paper — but instead were slices of bark taken from mulberry trees. The money that Polo would have first encountered in Asia would have been black and stamped with the Khan's red seal of verification.

Paper money was important in the Mongol Empire, as it allowed for Khan himself to control all the actual wealth in the form of precious metals, with the paper notes forming a "fiat" role and allowing him to expand the financial network of his territory on a scale Europeans would have found unthinkable.

Marco Polo introduced Europe to many Asian ideas -- but not pasta

Many other Asian customs and ideas were to be found in The Travels of Marco Polo, with paper money just one of the things recounted in the book that proved to be influential on European readers. The burning of coal for heat, the concept of a postal system, and never-before-seen accounts of unknown herbs and exotic animals are to be found in its pages, all contributing to the book's cultural significance and lasting impact.

However, despite what various corners of the internet say, Marco Polo is in no way responsible for bringing pasta to Europe. In fact, according to History, pasta dishes were being eaten by Europeans centuries before Polo's travels. The root of the myth is perhaps based on the common misconception that the Polos were the first Europeans to travel so far East. This isn't the case. Many Europeans had made it to Asia and beyond before Marco Polo did — it's just that his book, a combination of entertainment and social reportage, meant that his stories became the most widely circulated and the best known.

Marco Polo delivered the first known account of Japan to Europe

Readers found The Travels of Marco Polo and his tales of the Far East astonishing.

Part of this is perhaps down to the influence of his writing partner, whose experience writing romances helped to shape the book and give it its awestruck tone. Although Polo himself is the hero of the story, the book contains much material included by Rusticello for entertainment value, as well as accounts of distant lands which it is not believed Polo could ever have visited.

One of the most striking of these is Japan, which receives its first mention in a European text in Marco Polo's account of the Mongols' invasion of the country, which, at the time, was referred to as Chipangu, according to Voices of the Past. Polo described the island's bountiful reserves of gold, stating that the roofs of buildings are lined with it the same way that old church roofs are lined with lead, and how their palaces boasted solid gold floors and windows. His account must have had the scores of travelers who followed in his footsteps salivating.

Marco Polo claimed to hear spirit voices during his travels

Marco Polo obviously lived in superstitious times, but his background was Christian, specifically what we would consider today to be Catholic. Perhaps it is surprising, then, to note that The Travels of Marco Polo contains the traveler's claim that he heard the voices of strange spirits while he was on the road:

"When a man is riding through this desert by night and for some reason — falling asleep or anything else — he gets separated from his companions and wants to rejoin them, he hears spirit voices talking to him as if they were his companions, sometimes even calling him by name. Often these voices lure him away from the path and he never finds it again, and many travelers have got lost and died because of this."

While it's tempting to brush this away as fantastical thinking — or merely to say that this is an expression of the typical Catholic belief in the existence of demons — it's interesting to think of this in terms of Polo's leaving of Christian territory, namely Italy as part of the Holy Roman Empire, and entering a vast and unfamiliar space, uncontrolled by the Church and spiritually unknowable. In such situations, the explorer might have questioned whether familiar theological laws still applied.

Marco Polo returned to Venice to become a wealthy merchant

Marco Polo was released in 1299, after more than three years' imprisonment. According to Heritage History, he returned home to Venice, where he quickly set about his transformation from an adventurer to a settled merchant and family man, marrying soon after his arrival, becoming a father to three daughters, and successfully running the family business. It certainly helped that Polo still had the jewels and precious metals he had amassed on his travels, and that his family bought a huge palazzo as their new permanent home in Venice.

Like Marco Polo's early life, his time after returning to Venice — he died more than two decades later at the age of 70 — lacks much detail. But accounts claim that Polo was already a celebrity for his adventures and his book in his own lifetime, that he became a popular and important member of Venetian society, and that he was mourned greatly by the city at the time of his death.

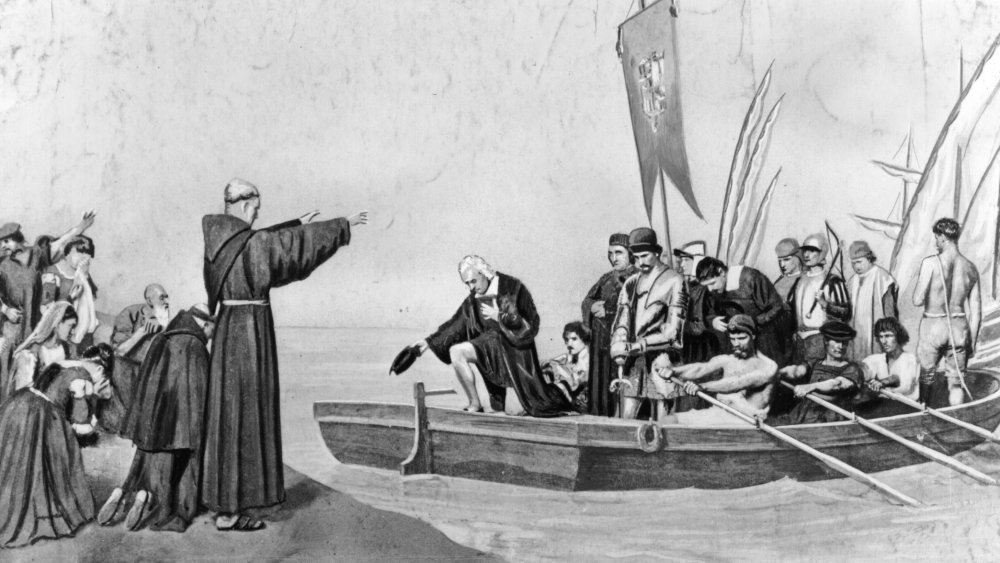

Marco Polo became a great influence on future explorers

The cultural impact of The Travels of Marco Polo cannot be overstated, but it has also been a major influence upon generations of travelers and merchants keen to replicate its adventurous and boundary-breaking spirit.

Shortly after the Polos returned to Europe, Kublai Khan was defeated and his empire overthrown. As a result, the trail that the Polos had first taken to Asia became cut off, and return became an impossibility for Europeans for decades. However, new horizons were opening up to European travelers, and the reputation of Polo's book only grew in these years. According to Britannica, the detail with which Polo's book explained the regional varieties of herbs and spices convinced generations of travelers to journey east in an attempt to circumvent established trading monopolies. Polo's account of Japan meant that Christopher Columbus would select it as his destination in 1492, while the later explorer is also reported to have taken a copy of Polo's book with him when he set off across the Atlantic in search of a route to the Far East.

The truth of Marco Polo's tales is up for debate

Though the book was popular, it has been widely reported than many of its early readers did not take Marco Polo's tall tales seriously and put the book down to an overactive imagination or downright duplicity. Polo, however, always stood by his book, reportedly stating on his deathbed: "I have not told half of what I saw."

But the debate has never quite ceased. According to History, some scholars have pointed to some of the book's glaring omissions — such as the Great Wall of China, the use of chopsticks, foot-binding, and the drinking of tea — as evidence that Marco Polo never actually made it to China at all and that his book is made up of numerous bits of gossip and rumor accumulated in Western ports during his days as a trader. More recent studies, however, have sought to cement his reputation and prove that his story is based on fact.

It could easily be argued, however, that it no longer matters. The story of Marco Polo's travels eclipses such debates and is undoubtedly one of the most influential tales of all time.