The Crazy Adventures Of Henry Morton Stanley

For all the dark sides of the Victorian era — massive exploitation of Native populations, plenty of abject poverty and horrible working conditions in the industrializing West, and brutal unsolved murders — there was some seriously cool stuff going on, too.

From world-changing inventions like the light bulb to scientific leaps like the theory of evolution, the Victorians were all about breaking new ground. Often literally: the Victorian age was a second great age of exploration, with Westerners heading out all over the globe to try to document, codify, and understand all the places their predecessors had brought to light (and the natives already knew well).

No wonder that scientists and geographers were huge celebrities at the time. They brought the world back to their admiring audiences in the West, giving them a glimpse of something unique and fascinating to break up the stink, smoke, and general daily grind of life in 1800s England and America.

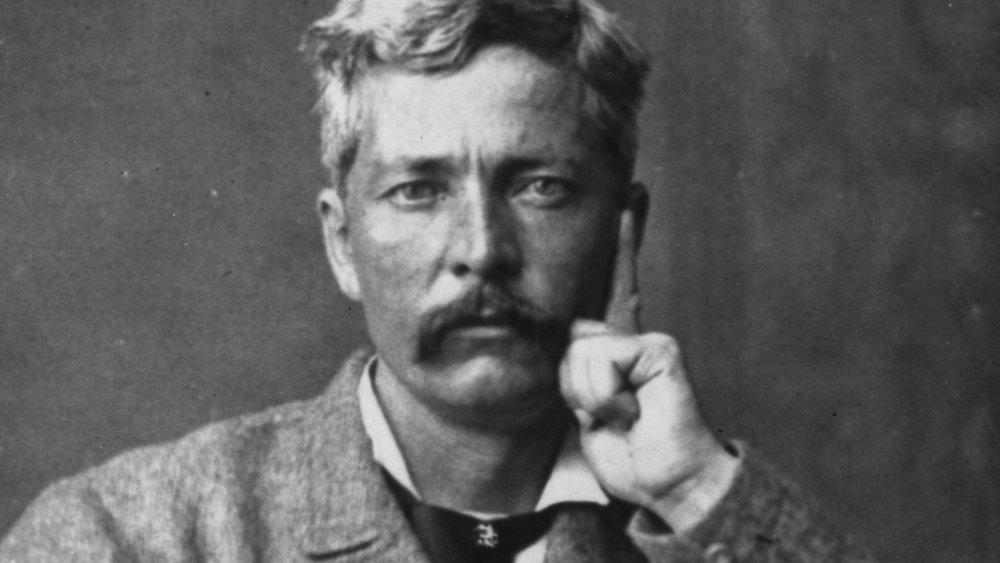

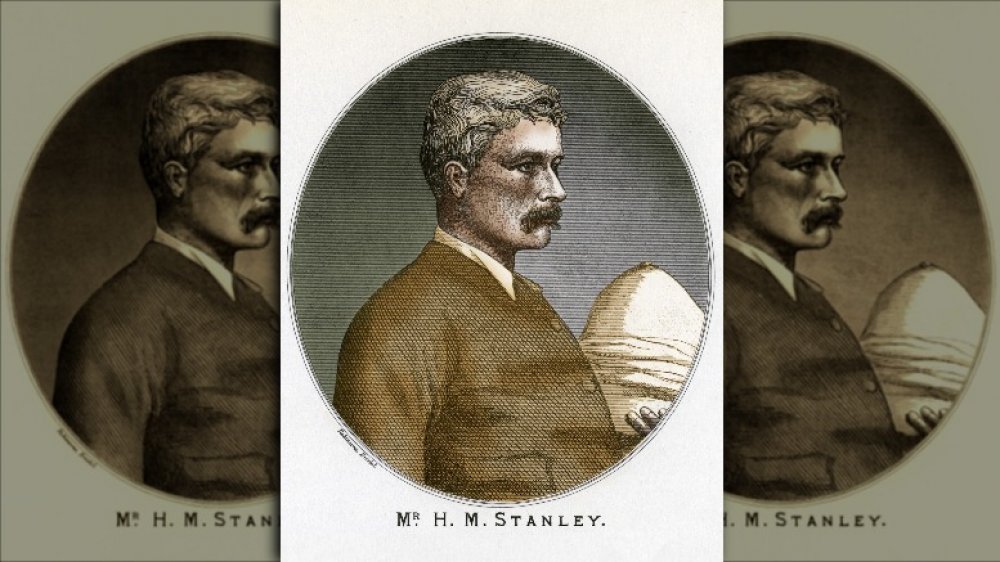

One guy who tailor-made himself for the job of Victorian Celebrity Explorer, despite having exactly no credentials, scientific or otherwise, was Henry Morton Stanley. Possibly best known as "that guy who found Livingstone," Stanley was so much more than that: clerk, sailor, newspaper writer, self-taught cartographer, full-blown colonizer, and Kardashian-scale self-promoter.

Who was Henry Morton Stanley?

One of the most famous quotes of all time is "Dr. Livingstone, I presume," but who was the guy who said it? Henry Morton Stanley was a sailor, mercenary, raconteur, quasi-journalist, and adventurer in his own right, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. Stanley wasn't just "that dude who found that other dude," though that ended up being a pretty big theme in his life.

Stanley created his own identity literally from scratch at least three times; made some epically long journeys through Africa, creating the first maps made by westerners there; and wrote super-popular bestselling books about his adventures. Basically, as the BBC relates, the guy was a self-made Victorian reality star who put our modern self-promoting influencers to shame when it came to creating a backstory and pulling headline-making stunts. As Smithsonian Magazine puts it, he essentially used iron willpower and a visceral need for personal recognition to rise from nothing and create a legacy (a troubling one, to boot) that would endure for more than a century.

Henry Morton Stanley's early life

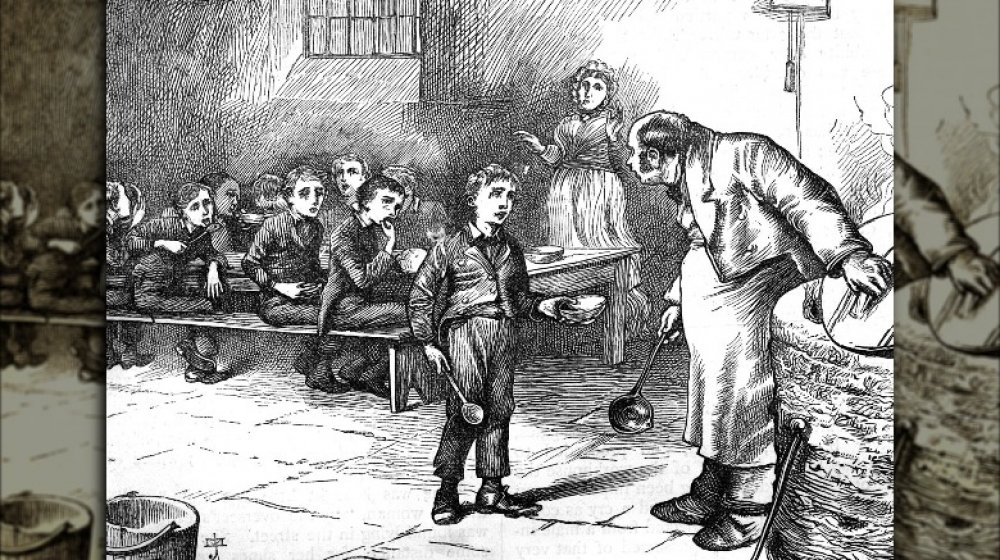

Henry Morton Stanley was born on January 28, 1841, as John Rowlands, to an unmarried couple in Denbigh, Wales, as the Encyclopedia Britannica relates. Being a bastard, and therefore completely shut out from any decent prospects in prim and proper Victorian society, he had a pretty dismal childhood. Young Stanley bounced between indifferent relatives for years and ended up in a workhouse, according to the New World Encyclopedia.

Later on, he wrote of all kinds of atrocities and abuse in his early years in various books and autobiographies, but near as any modern scholars can tell, this was almost all inflated fantasy meant to make his rags-to-riches story all the more sensational.

Still, even if it wasn't as quite as bad as Stanley himself made it out to be, if Charles Dickens has taught us anything, it's that the life of a Victorian kid in a workhouse sucked. So it's no wonder that Stanley fled to America promptly upon busting out at age 15.

Stanley reinvented himself in America

Despite being Welsh by birth, Henry Morton Stanley loved America on general principle. Where better for someone with a slightly dodgy past to completely reinvent himself than a self-made country? Plus, the American spirit of adventure suited him just fine. In the United States, Stanley could leave behind class status and issues of birth and create his own background ... and future.

And according to Historic UK, that's just what he did, working in the merchant marine, getting bored doing a couple of desk jobs, and practicing his writing chops by scrawling bad self-insert war fanfic whenever he could. In an excerpt from his autobiography, HistoryNet relates that he got a pretty exciting start to his new life from Day 1: His first night in New Orleans, at age 16, he ended up at a brothel with the other sailors where "the girls took liberties with [his] person."

Something about the experience must've agreed with him because Stanley jumped ship and stayed in New Orleans in 1857. He ended up as the protégé of Henry Hope Stanley, a wealthy cotton broker who gave the ragged boy then known as John Rowlands a job and an education, according to the Dictionary of Welsh Biography. At some point, their relationship got super-weird. The boy started calling himself Stanley and the original Henry Stanley sent the kid away, possibly for being a little too Parasite for comfort.

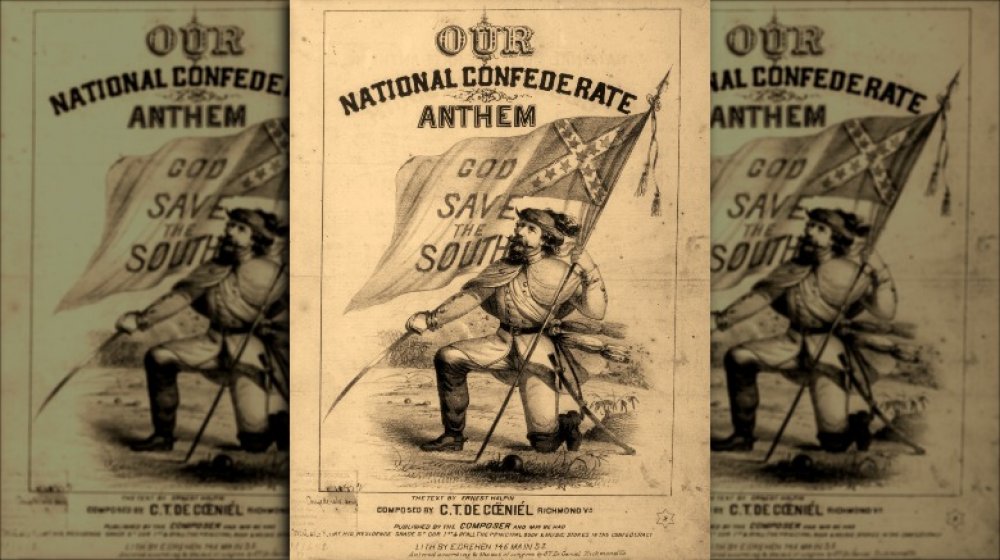

Henry Morton Stanley fought on both sides of the Civil War

No longer in the anything-goes sin city of New Orleans, but stuck working at a country store in Arkansas after falling out with his rich mentor, young Henry Morton Stanley was getting restless.

One proven way to add some spice to your life is by heading for the nearest local war. That must've seemed like a great idea to young Stanley, who ended up fighting for both the Confederacy and the Union during the US Civil War. Calling himself William H. Stanley, he signed up with the Confederate infantry in 1862 and, according to his autobiography, apparently thought that it was going to be all sunshine and roses (well, picking violets). That idea got nixed fast when one of his buddies promptly got shot.

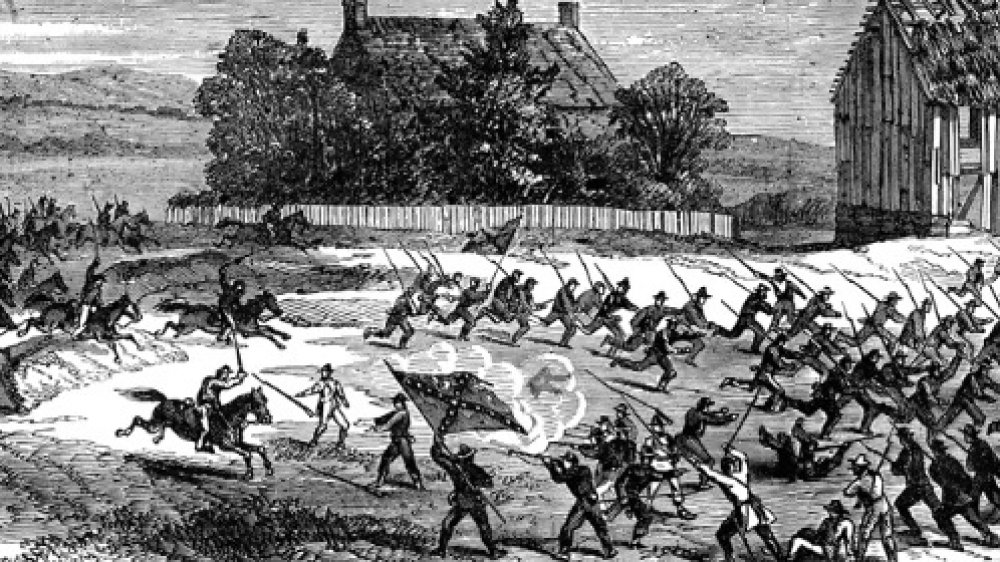

The very next day, Stanley got winged by a bullet, hid behind a tree, and was captured by the Union. It was off to prison camp for Stanley. At Camp Douglas outside Chicago, Stanley was crammed with tens of thousands of other Confederate POWs into "80 acres of hell," as historians have referred to it. He somehow managed to survive, despite the nasty mortality rate — as the Encyclopedia of Chicago tells us, about 1 in 7 prisoners died.

However he managed, Henry Morton Stanley got through long enough to be offered a deal: switch sides and get out of this hellhole. Stanley promptly accepted the offer.

Stanley deserted the military multiple times

Stanley promptly changed his name again, leaving Camp Douglas as Private Henry Stanley of the Union Army and heading for Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Hospitalized with dysentery there, he was incredibly sick — but not so sick that he couldn't check himself out of the hospital and desert the Army. Once on the mend, he hopped a ship back to Wales in 1863.

But back home, things were no better. According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, he was rejected by his mother and her new family, couldn't get a job, got depressed, and hopped another boat back to America, where he enlisted in the Navy (all those name changes helped cover up the fact that he was a deserter and a Confederate). HistoryNet tells us that he spent most of his time making up wild stories about how he performed all kinds of courageous feats.

But he did manage to sell some stories to newspapers, which spurred a new hobby after the war: traveling West as a freelance correspondent. In his autobiography, Stanley glosses over this time except to relate a few tales of youthful hijinks and to tell us that he was becoming something of a hot commodity as a writer. It was the start of his real career as an explorer and self-promoter.

Stanley got his big break as a newspaper stunt

The self-promotion totally worked, though. Despite being pre-social media, Henry Morton Stanley managed to gin up a super-cool reputation for himself as someone who fearlessly forged into dangerous places to do stupid things. It didn't hurt that Stanley had a flair for the dramatic and could write gripping accounts that captivated his audiences.

"Thrilling man of adventure" was the perfect gig for Stanley. Victorian Britain and America were obsessed with exploration; Americans were pushing further and further west, while Brits were off poking their noses into every corner of the globe. A particularly popular pastime was searching for the source of the Nile River. One explorer looking to clear up a longstanding debate about which lake the river originated in was Dr. David Livingstone of Scotland, who vanished on his 1866 expedition, as History.com tells us.

James Gordon Bennett, the publisher of the New York Herald, figured sending an American to find him would prove that the good ole' USA was hardier, smarter, and just generally better than those tea-drinking Brits, as The New Yorker sums it up. Of course, when Bennett picked scrappy young reporter Henry Morton Stanley for the job, Stanley had done such a great job erasing his own history that the super-nationalist publisher had no clue the guy was actually Welsh.

Dr. Livingstone, I presume?

So it was off to Africa and the chance of a lifetime to make a name for himself.

Henry Morton Stanley had basically no experience when it came to anything beyond improvisation, but he was an absolute legend at that. After arriving in East Africa, he hooked up with the local rumor mill, got word of a crazy white guy who might be Livingstone, and joined a caravan of Arab slave traders, according to ThoughtCo.

The trip didn't go well. Apparently thinking, yet again, that everything was going to be sunshine and roses, Stanley started out with an insane amount of supplies and a luxurious all-white outfit. Within days, Historic UK says, his horse died and his native employees started deserting the expedition due to his abuses.

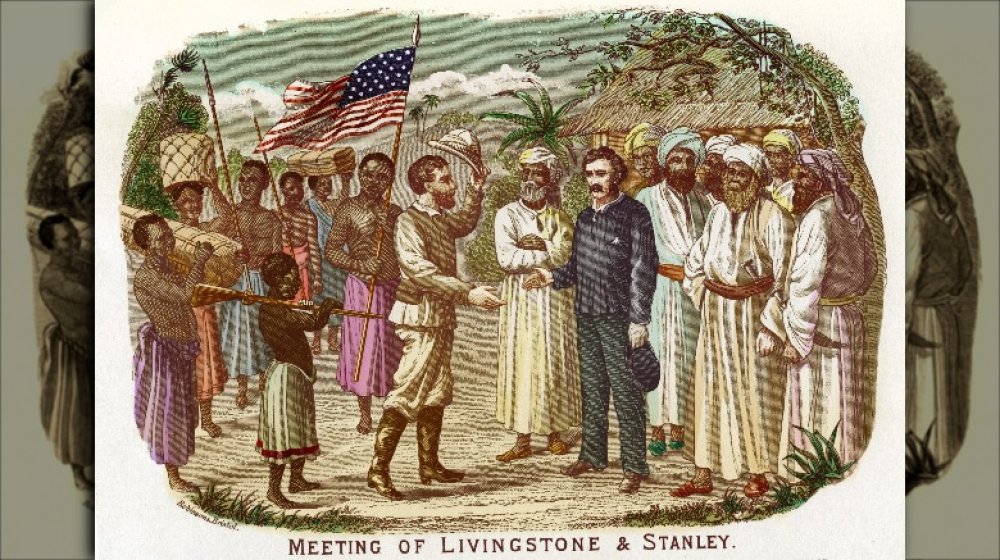

Still, Henry Morton Stanley somehow managed to survive crocodiles, malaria, attacks by furious natives, and his own arrogance to arrive in the city of Ujiji, making the 700-mile trip in 236 days.

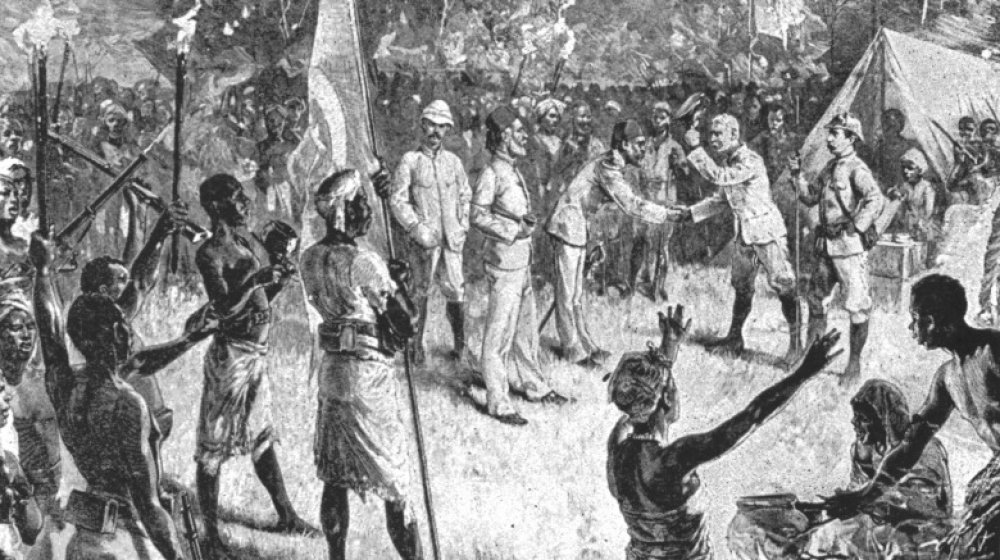

There, in the fall of 1871, he found Dr. David Livingstone, frazzled, sick, horrified by the local slave trade, and yet unwilling to go back to Jolly Old Repressive England, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Interestingly, although Stanley journaled obsessively and wrote about his life incessantly for his admiring audiences, the page about the day he met Livingstone is missing, as Smithsonian relates. So we don't actually know if he really said his famous line, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" But hey, he said he said it. Good enough.

Henry Morton Stanley confirmed the source of the Nile

With Livingstone safely found, Henry Moton Stanley realized he didn't want to go back to the States just yet — there was just too much potential for a few more great stories.

After helping Livingstone recover from his latest bout of malaria, the two teamed up to finish what Livingstone had gone to Africa to do: confirm the source of the Nile. According to Encyclopedia.com, they became the first Westerners to circumnavigate Lake Victoria. They also proved that Lake Tanganyika, which was an alternative source for the Nile, had no connection to the river, per the Encyclopedia Britannica. So Lake Victoria it was. The debate was finally solved, and the Nile's source was known.

Stanley headed back to England in 1872, intent on publishing a memoir of his time in Africa and making a quick buck on having not only found Livingstone but the source of the Nile, too. But Stanley found himself in a pickle: according to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the English resented that a supposed American had gotten the bragging rights, and yet America didn't seem important enough for Stanley's dreams of glory.

Fame wasn't enough for Henry Morton Stanley

Back in Britain, Henry Morton Stanley found a great deal of fame, just not in the way he wanted. He was still playing second fiddle, known just as "that guy who found Livingstone." For someone with an outsized ego, it wasn't ideal.

After publishing his book, doing a lecture tour, and finding his 15 minutes of fame running out, it was time for another stunt. Stanley decided to go back to Africa. After Livingstone's death in 1873, as the BBC notes, Stanley put together backing for a new expedition, supposedly aimed at "continuing the great explorer's legacy," but really an excuse to get back in the field.

Stanley pitched it to the newspapers that backed him as the chance to solve one of the last big geographic mysteries of the day now that the whole Nile thing had been cleared up. Where, exactly, did another big river, the Congo, flow?

History Today relates that he went about this second journey pretty much like every trip before it: with an excess of confidence and gear, totally convinced that whatever he did was exactly the right thing, evidence to the contrary be damned.

Stanley adventured through the Congo for a King

Heading westward from Lake Tanganyika, Henry Morton Stanley took a massive expedition down the Congo basically to see what would happen.

As Historic UK reports, while cruising more than 7,000 miles through Central Africa to the Atlantic Ocean, Stanley faced more than a few obstacles — which killed his three white companions and probably a few dozen natives hired to help. Still, Stanley's luck held and he survived the nearly thousand-day journey to come out, once again, an adventurous hero in the eyes of Victorian society, according to Encyclopedia.com.

Doing a bang-up job of self-promotion, Stanley wrote a few more books, such as Through the Dark Continent in 1878, then got his next gig. He was hired by King Leopold II of Belgium, who wanted to set up trading stations throughout the Belgian-controlled Congo region. Stanley quickly turned the Congo into a hotbed of exploitation, death, and unimaginable abuse of the natives, as the BBC notes.

Henry Morton Stanley may or may not have known the atrocities left in his wake. However, we're also not sure he would have cared; he didn't seem to show much empathy for his native employees in his writings. As Headstuff.org says, even in a time known for brutal treatment of anyone who wasn't a rich white European guy, Stanley was infamous for being a particularly violent maniac. But then, he mostly seemed to view other people as a means to an end, regardless of their race, so draw your own conclusions.

That time Stanley "rescued" Emin Pasha

After setting the stage for one of the most violently racist colonial regimes in Africa, Henry Morton Stanley headed back to England.

Yet again, he proved he didn't do too well with settled life in the West. His wife had married another man and his books weren't selling and, frankly, he was bored to tears. So Stanley packed up and headed back to Africa on yet another so-called "rescue" mission.

This time, his goal was to "save" Emin Pasha, a German-born doctor and explorer who was caught up in a religious uprising in the territory of South Sudan where he served as governor, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

Granted, Emin Pasha didn't actually want to be rescued, as the British National Archives relate. Pasha was cut off from the outside world by the rebellion, true, but he was also a super-charismatic diplomat and world traveler who was doing his best to sort the situation out peacefully. Stanley's entirely unexpected arrival with a bunch of armed troops in 1888 just made things more difficult for the poor guy, who was trying to wade through peace talks at the time.

But little things like diplomacy never bothered Henry Morton Stanley in the pursuit of headlines. He essentially strong-armed Emin Pasha into ditching out on his responsibilities and retreating to Zanzibar. The two had to put down a mutiny that probably wouldn't have happened without Stanley's interference. But hey, it made for another great story, right?

Stanley finally settled down, with a troubling legacy

Having had a bit of an embarrassment in that last adventure, what with his "helpless victim" turning out to be doing perfectly fine, Stanley finally headed back to England for the life of an acclaimed gentleman in 1890.

As the BBC tells us, Stanley got married, did a worldwide lecture tour, got elected to Parliament, got knighted, and generally lived a life completely unexpected for a bastard kid from Wales.

However, there's a good bit of debate about Henry Morton Stanley's place in history today. Given his adventures, he's ripe for a TV series or two, maybe some movies ... but he was also a bigot, a violent sociopath, and a massive racist.

Granted, most white Victorians were racist as all get-out, but Henry Morton Stanley had a particularly nasty tendency to spread vicious rumors about "uncivilized" African natives as a way to promote his own fame and fortune. With that in mind, there's considerable debate about how he should be remembered today, including talk of taking down statues and memorials to him as part of Black Lives Matter, as a recent BBC article notes.

It just goes to show the power of guts, drive, ego, and a healthy dose of narcissism — and that being a racist, in the case of Henry Morton Stanley, can catch up to you, even a century down the line.