Magnus Hirschfeld: The Tragic Story Of A Gay Rights Pioneer

Had history transpired differently, Magnus Hirschfeld's work could've had lasting worldwide influence on sexology and gender studies. His early research could've been a springboard for contemporary theories and understandings.

But neither Hirschfeld nor his research got the chance to survive. Hirschfeld's sexological work was already controversial during his own time, and when the Nazis took power in 1933, they did their best to destroy any trace of his research. Many say that Hirschfeld himself died of a broken heart after witnessing the destruction of his Institute for Sexual Science in newsreel footage while in self-exile in Paris. His life's work on topics such as homosexuality, gender, and abortion went up in flames, and thousands of irreplaceable photographs, artifacts, and medical records were lost.

While Hirschfeld may be considered incredibly progressive for his time, he simultaneously adhered to some of his era's prevailing methodologies, such as the desire to find a biological explanation for gender and sexuality. But while some of his theories would've been disregarded today, much could've been expanded upon, had it survived. It's impossible to determine how much gender studies and sexology were set back by the destruction of Hirschfeld's Institute for Sexual Sciences. But his legacy lives on in the continued battle for LGBTQI+ rights. This is the tragic story of a gay rights pioneer.

Magnus Hirschfeld's early life and study of medicine

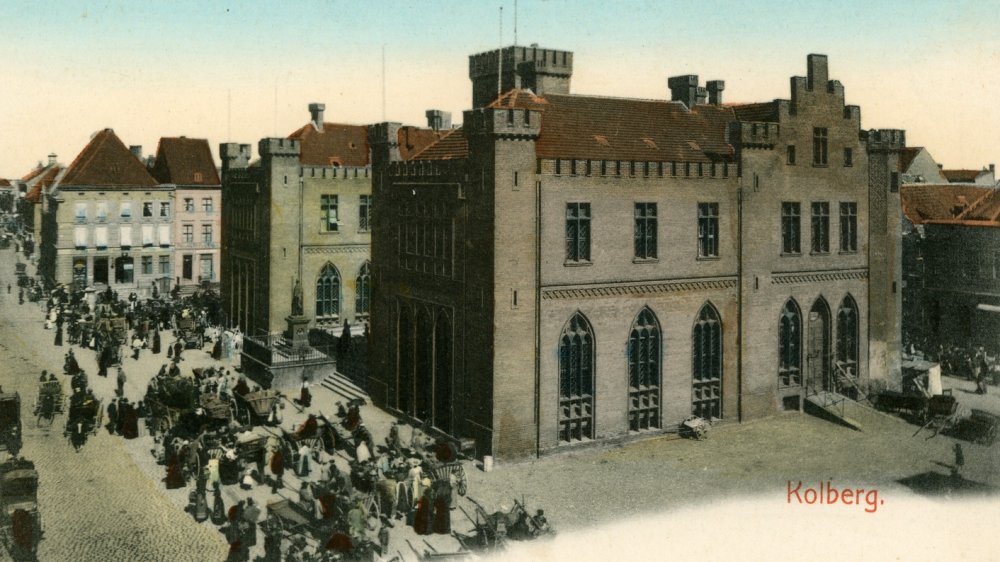

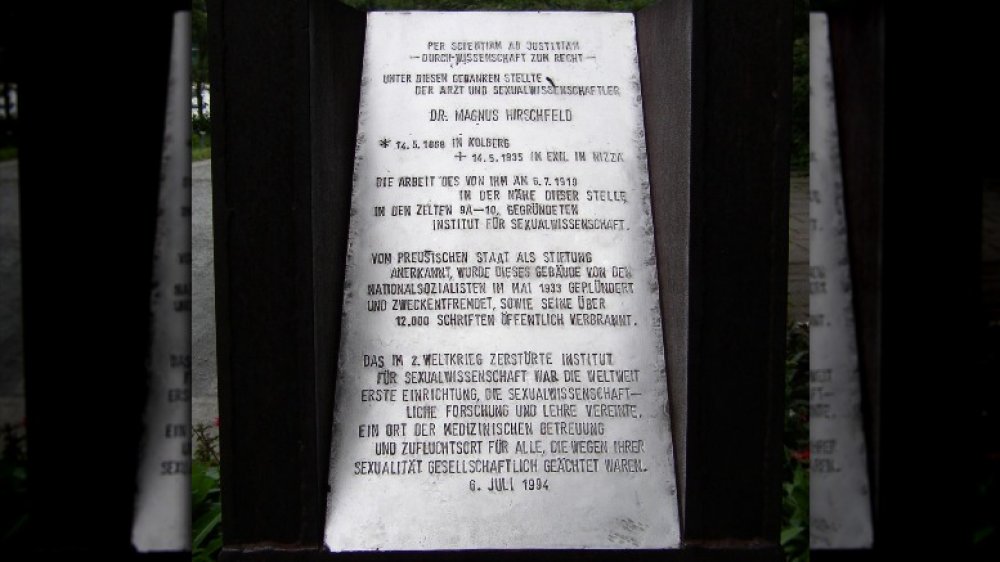

Magnus Hirschfeld was born on May 14, 1868, in what was Kolberg, Prussia, though it is now considered now Kołobrzeg, Poland. Hirschfeld was born into a conservative Jewish family, according to the Peter Tatchell Foundation, and his father, Hermann Hirschfeld, had also been a medical doctor.

According to Magnus Hirschfeld by Ralf Dose, translated by Edward H. Willis, during the 1870-71 war, Hermann Hirschfeld earned a Prussian commemorative medal for the medical services he provided to French soldiers, and after his death in 1885, the residents of Kolberg even put up a monument in his behalf. Unfortunately, less than 50 years later, the residents of Kolberg destroyed the very same monument when the Nazis came to power in 1933, no longer able to tolerate a monument to a Jewish person.

Even as a child, Hirschfeld thought that sexuality was wholesome and natural, and he was horrified during his studies when an incarcerated gay man was brought out in front of medical students at the University of Strasbourg. According to Oscar Wilde and Modern Culture, edited by Joseph Bristow, Hirschfeld was also inspired by the trial against Oscar Wilde in 1895. And when a patient of his committed suicide the following year, challenging Hirschfeld in his suicide letter to educate others on the plight of homosexual people, Hirschfeld decided to devote his life to the study of sexuality and advocacy for sexual minorities.

Homosexuality around the world

Before attending medical school, Hirschfeld tried his hand at journalism. Taking a ship to New York from Hamburg with a friend, he ended up writing a report on Chicago's World Exhibition in 1893. During his time in Chicago, Hirschfeld briefly interacted with Chicago's queer community, but he later noted in his research that the queer community was less visible in the United States than in Europe. According to Reconsidering the Emergence of the Gay Novel in English and German by James Patrick Wilper, during his travels through Boston and Philadelphia, Hirschfeld rarely encountered homosexuals but was told that there were a great deal in the intimate circles of Puritans and Quakers.

After witnessing the queer subcultures in Chicago and Berlin, Hirschfeld began to develop a theory of the universality of homosexuality. Arguing that homosexuality was a "naturally occurring, global phenomenon," Hirschfeld even claimed that the homosexual graffiti in Chicago bore resemblances to graffiti in Tokyo, Tangier, and Rio de Janeiro. At one point in his life, Hirschfeld reportedly calculated that there were 43,046,721 possible varieties of human sexuality, claiming that "love is as varied as people are."

However, according to The Hirschfeld Archives by Heike Bauer, in his desire to normalize homosexuality, Hirschfeld propagated the language of scientific racism and colonialism by publishing anthropological studies of "[sexual practices] among Naturvölkern (primitive peoples) to support its argument that homosexuality was a naturally occurring phenomenon in the distinct group of Kulturvölker (civilized peoples)."

The Scientific Humanitarian Committee

In 1897, Hirschfeld founded the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee, WhK, also known as the Scientific Humanitarian Committee, which was the world's first homosexual organization. Campaigning for queer rights, the WhK fought to repeal Paragraph 175 of the Imperial Penal Code, which criminalized homosexuality between men in Germany.

In 1898, Hirschfeld introduced a petition to abolish Paragraph 175. According to Reconsidering the Emergence of the Gay Novel in English and German by James Patrick Wilper, the petition outlined the humanitarian and scientific reasons for repealing Paragraph 175 and amending it so that the only homosexual acts that are punished are those involving coercion or public annoyance. According to Queer Identities and Politics in Germany by Clayton J. Whisnant, Paragraph 175 was inconsistently and arbitrarily enforced. The Berlin police often ignored the sexual activity of powerful and wealthy men and instead targeted lower classes.

The petition was ultimately unsuccessful, but according to The Hirschfeld Archives by Heike Bauer, so was an attempt to criminalize homosexuality between women. However, despite its failure, the petition garnered 900 signatures of lawyers, scientists, and civil servants. In less than 20 years, the number of signatures would number over 3,000 and include public figures such as Thomas Mann, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Frank Wedekind.

Magnus Hirschfeld's early support of transgender people

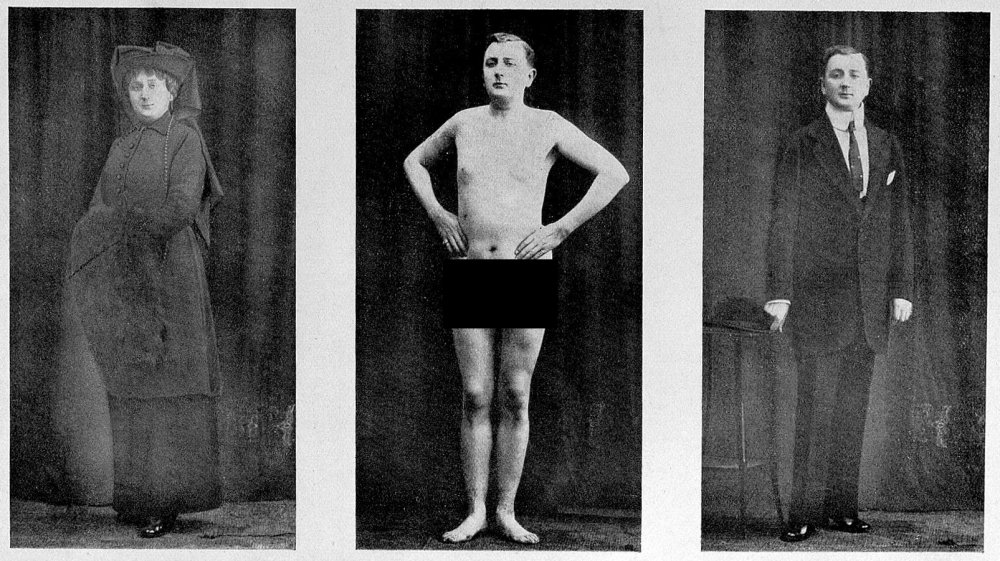

Following the work of Karl Heinrich Ulrich, Hirschfeld categorized homosexual people as "the third sex" and "sexual intermediaries." However, his research and activism included all those who didn't fit into a cisgendered, heteronormative category. According to The Paris Review, Hirschfeld coined the term "transvestite" in 1910, seeking to describe transgender people and people who cross-dress. Some gay men took offense at Hirschfeld's language, noting that it might propagate inaccurate stereotypes, but people had been emboldened by Hirschfeld's efforts and became increasingly vocal about queer social reform.

According to Atlas Obscura, Hirschfeld was able to pressure the police to create ID cards that authorized people to dress according to the gender of their choosing. While cross-dressing wasn't technically illegal, people were subject to the whims of the police and could be charged with being a "public nuisance," which could come with a fine of 150 marks or six weeks in jail.

In 1910, Hirschfeld and Iwan Bloch came to an agreement with the police that arrests would be waived if someone presented a "transvestite certificate." According to the Magnus Hirschfeld Society, Hirschfeld also worked with lawyer Walther Niemann to allow transgender people to change their first name to gender-neutral names. Within 20 years, Hirschfeld would go on to advocate for and perform gender confirmation treatment and surgery. In 1931, Dora Richter was the first person to have a complete gender confirmation at Hirschfeld's Institute for Sexual Science.

Magnus Hirschfeld's involvement in feminist activities

Hirschfeld was also notably involved in feminist organizations. When it was founded by Helene Stöcker (pictured above) in 1905, Hirschfeld joined the Bund für Mutterschutz, BfM, also known as the League for the Protection of Mothers. In 1909, he joined her in lobbying the Reichstag not to criminalize lesbians. In addition to his work on homosexuality, Hirschfeld also advocated for contraception, abortion, sex education, and marriage reform.

According to the Magnus Hirschfeld Society, with Stöcker, Hirschfeld advocated for the repeal of Paragraph 218, which criminalized abortion. Hirschfeld and Stöcker were so persistent and revolutionary in their views that they came to be known as "sex radicals" by their contemporaries, and not in a good way. According to Magnus Hirschfeld and the Quest for Sexual Freedom by E. Mancini, Hirschfeld's consideration of women was comparatively progressive, especially in his acknowledgement of women's sexual desire and pleasure.

Hirschfeld sought to embrace a wide variety of feminist causes, such as the legitimization of wedlock children and women's right to education. However, according to The Hirschfeld Archives by Heike Bauer, Hirschfeld perpetuated a Western mentality that centered on men during his later travels around the world. Despite the fact that he met with many women sexual reformers around the world, his text The World Journey fails to give them a voice, which is "doubly problematic given the text's anticolonial [sic] framework and emphasis on the existence of localized yet internationally connected feminist and sexual reform movements."

The Harden-Eulenburg affair

In 1907, Magnus Hirschfeld became involved in the Harden-Eulenburg affair, a scandal involving journalist Maximilian Harden and Prince Philipp Eulenburg. According to the European University Institute, in 1906, Harden began a press campaign against Kaiser Wilhelm II, claiming that the emperor had surrounded himself with degenerates, among whom Harden named Prince Eulenburg as the leader. The scandal involved six trials, the first of which occurred when Count Kuno von Moltke sued Harden for libel after Harden claimed that Molke was "sexually abnormal." During the trials, Hirschfeld testified against Molke, bringing issues of queer identity and homosexuality into public discussion for the first time.

While Hirschfeld was effectively participating in a public "outing," he was more concerned about having the chance to discuss the validity of sexuality in a public forum and claim the Kaiser's friends as part of his movement. Hirschfeld also validated the testimony of Lilly von Elbe, Count Moltke's ex-wife. According to The Eulenburg Affair by Norman Domeier, many thought Elbe's sexual desire was immodest and considered her testimony to have violated the rules of public decorum. Women who expressed such sexual desire were considered not only unwell but "unfeminine." Hirschfeld defended her desires as natural and used them to illustrate that Count Moltke was "subconsciously homosexual."

The jury agreed and acquitted Harden. Moltke and Harden had two subsequent trials against one another, and Harden was convicted of libel in both.

Magnus Hirschfeld and Weimar Germany

After World War I, the Weimar Republic sought to establish progressive social practices, which led to Berlin becoming one of the most socially liberal places in Europe. In this environment, Hirschfeld was able to establish the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft, also known as the Institute for Sexual Science, in 1919.

According to The Hirschfeld Archives by Heike Bauer, the institute can be considered the first full-scale archive of sexual science in the world. Hirschfeld and his colleagues amassed an incredible library with clinical notes, books, journals, and visual material. As noted by Hornet, the institute also provided a range of services, ranging from marriage counseling to gender confirmation surgery. Hirschfeld wanted to ensure that the services of the institute were accessible to everyone, so he often provided low or no-cost treatments. The institute was also one of the only places that employed transgender people.

Ultimately, Hirschfeld took a considerably biological approach and hoped to use scientific reasoning to convince the German public that differences in sexuality and gender were natural. He distributed questionnaires to establish the rates of homosexual and bisexual desires and sought to establish a biological connection to sexual orientation. While Hirschfeld pushed against the gender binary, his desire to scientifically validate sexuality and gender unfortunately led him to perpetuate biological essentialism.

Magnus Hirschfeld perseveres against abuse

Despite the more liberal atmosphere of Weimar Germany, Hirschfeld and his unwillingness to compromise on his beliefs made him a target for a great deal of abuse. He was also demonized for his Jewish heritage. According to Antisemitism by Richard S. Levy, Hirschfeld's lectures were frequently interrupted by rude remarks, catcalls, and stink bombs.

After one lecture in 1920, Hirschfeld was attacked by a group of right-wing people who beat him to within an inch of his life and left him for dead. Indeed, he had been beaten so badly that many assumed he was dead. According to the Internationalist Group, Hirschfeld ended up reading his own obituary in the newspaper. Many of Hirschfeld's detractors even lamented that "this poisoner of the Volk hasn't died already."

In 1929, Hirschfeld was forced out of the Scientific Humanitarian Committee for reportedly accepting kickbacks in exchange for promoting unsuitable medicine. However, it's unclear whether he actually was doing so, and it's also likely that Hirschfeld was forced out because his Jewish heritage made him a political liability.

Magnus Hirschfeld embarks on a speaking tour of America

After being forced out of the Institute for Sexual Sciences, Magnus Hirschfeld left Germany to begin an international speaking tour. While Hirschfeld may not have intended at the time to leave Germany for good, he was aware of how precarious his future was, so he eagerly accepted an invitation from Harry Benjamin to lecture throughout the United States.

According to "Magnus Hirschfeld" by J. Edgar Bauer, upon his arrival, Hirschfeld was heralded as the "Einstein of Sex." Arriving in New York in 1930, he presented a variety of talks to both German- and English-speaking audiences. However, he tailored his lectures depending on his audience. While to German-speakers, he lectured relatively openly about sexuality and its variances, for English-speakers, his lectures pivoted toward "scientific partner selection and eugenic marriage counselling."

This change of appeal for English-speaking American audiences and "straight turn" was most likely an attempt by Hirschfeld to maintain a level of acceptance in America while he considered his impending political exile. According to the NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project, during his time in New York City, Hirschfeld met a variety of artists and activists such as Langston Hughes, Carl Van Vechten, and Margaret Sanger.

After realizing the extent of the antisemitic wave in Germany, Hirschfeld extended his speaking tour and traveled to Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

Magnus Hirschfeld travels around the world

After traveling across the United States, Hirschfeld was once more advised to extend his speaking tour. According to "Magnus Hirschfeld" by J. Edgar Bauer, Hirschfeld left San Francisco in March 1931, traveling to Japan, China, Indonesia, the Philippines, and India. His travels continued through Egypt and Palestine before he arrived back in Europe in March 1932.

During his world tour, Hirschfeld compiled and published a variety of sexual ethnographies. According to Queer Identities and Politics in Germany by Clayton J. Whisnant, the ethnographies are notable for their "conscious eschewal of a Euro-centric perspective." However, as Heike Bauer notes in The Hirschfeld Archives, Hirschfeld's claimed feminist and anti-colonialist allegiances come under dispute when one considers his erasure of women's voices, especially during his travels in India.

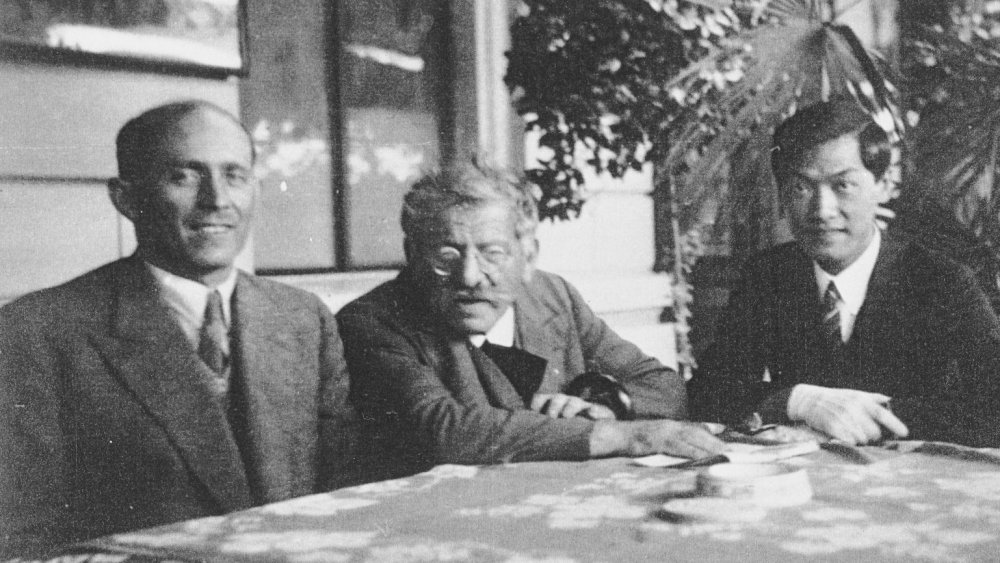

While Hirschfeld was in Shanghai, he met Li Shiu Tong (pictured above), who became his interpreter, traveling companion, and lifelong lover. Hirschfeld reportedly called him "Tao Li," which meant "Beloved Disciple." According to The World of Wonder Report, Hirschfeld also had a relationship with his archivist Karl Giese, and while there had been initial jealousy, upon Hirschfeld's return to Europe, the three of them lived together in Paris. Hirschfeld ended up naming both Li and Giese as the sole heirs to his estate.

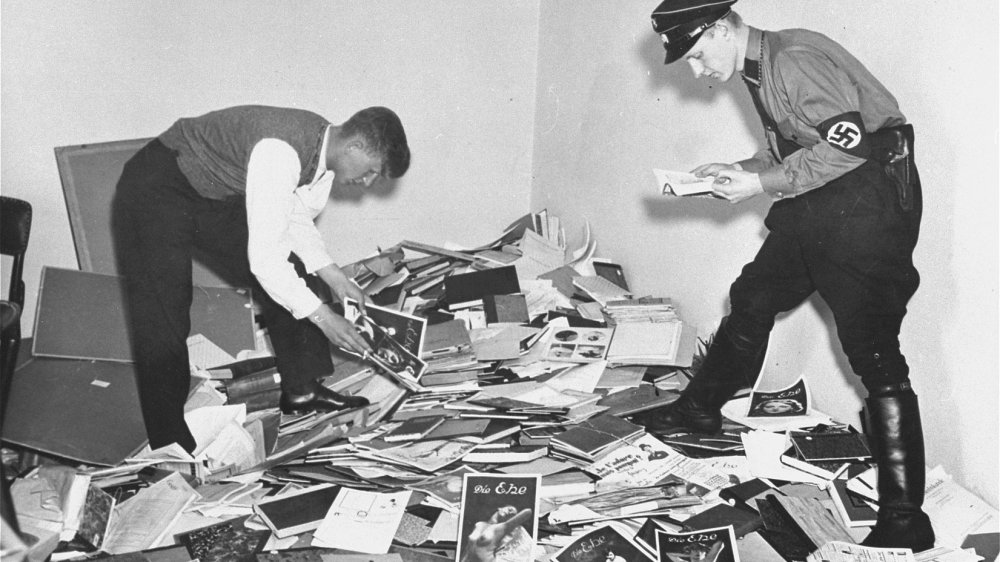

The burning of the Institute for Sexual Science

After Hitler officially took over as chancellor on January 30, 1933, the Nazis legitimized their attack on Germany's LGBTQI+ community. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, gay men were targeted because not only were they considered to be corrupting German culture and values, but they were also derided for not contributing to the growth of the "Aryan population."

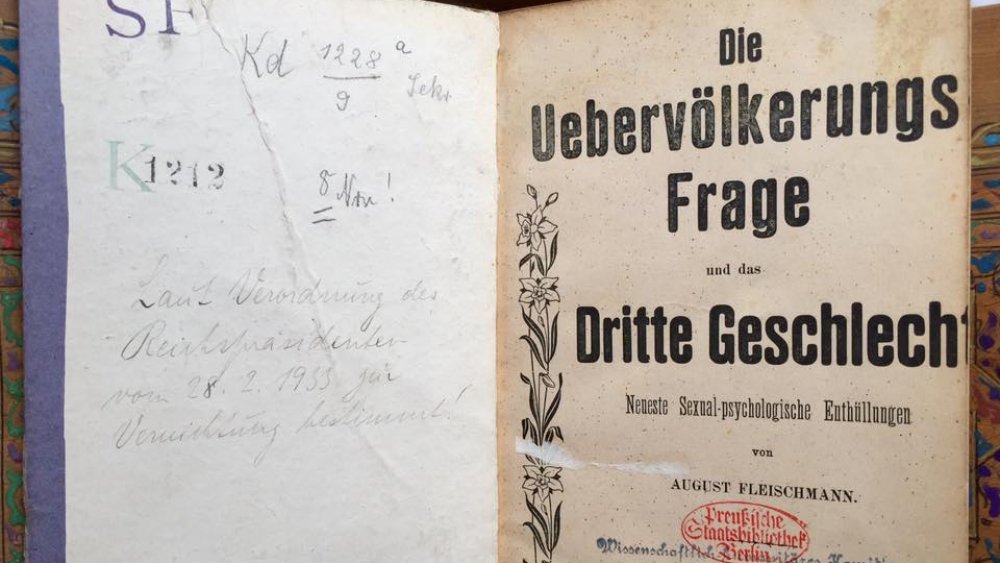

Less than six months after Hitler's rise to power, Nazis and fascist demonstrators invaded the Institute for Sexual Science on May 6. According to Teen Vogue, over 20,000 books were taken from the institute's library. On May 10, all the books were burned at Berlin's Opera Square. According to The Conversation, countless photos, publications, medical records, and artifacts were destroyed as well. Even a bust of Hirschfeld was taken during the raid, skewered and carried on a stick, and burned in the bonfire.

Many of the residents of the institute were killed during the attacks, and those who survived were sent to concentration camps. Hirschfeld found out about the looting of the institute while watching newsreels at a cinema in Paris. While the buildings of the institute were confiscated by the Nazis and sold to the state, according to the Magnus Hirschfeld Society, what remained of the buildings was destroyed during the 1943 bombings.

Magnus Hirschfeld's self-exile and death

When Magnus Hirschfeld returned to Europe in 1932, he realized that there was no way for him to go back to Germany, given the state that it was in. Writing in his travelogues, Hirschfeld lamented, "Poor, German fatherland! Beautiful, beloved home, will I see you again?" And although Hirschfeld had been harassed and attacked before, the spring of 1932 was the first time that he feared for his life.

According to The Hirschfeld Archives by Heike Bauer, Hirschfeld briefly tried to resume lecturing in Switzerland. But after the destruction of the institute, he realized that his former colleagues might betray him, so he fled Ascona, Switzerland. Hirschfeld briefly settled in Paris with Li and Giese, where they tried to found another institute for sexual sciences, though they were ultimately unsuccessful.

According to Making Gay History, Hirschfeld's depression and declining health led him to relocate to the warmer climate of Nice in the south of France in 1934. Unfortunately, his mental and physical health continued to decline. Tragically, Hirschfeld died one year later of a heart attack on his 67th birthday on May 14, 1935. Hirschfeld had hoped that Giese and Li would continue his work after his death, but Giese took his own life within three years, and Li never ended up publishing any of Hirschfeld's research.