The Legend Of The Mythical City Of Gold Explained

Gold has captured the human imagination for thousands of years. It's easy to understand how it got that way. Once it's been shaped and polished, gold has a luster much like the sun. In many cultures, people have drawn a direct connection between shining gold and deities. And, well, if a little bit of gold is nice, then wouldn't an entire city made out of the stuff be a marvel beyond all imagination?

Take the glorious specter of a city of gold and add in the dramatic possibilities colonizers must have envisioned when they first landed in Central and South America in the 16th century. That was the legend of El Dorado, National Geographic says. For Europeans, this was a fabled vast land that was potentially teeming with riches. For the Indigenous people who lived across the region, the mythical city may have had roots in deeply held religious beliefs and rituals. Or, eventually, tales of the golden lands may have been a way to distract the dangerous conquistadors. We don't have any gold here, but maybe if you travel a few hundred miles and bother someone else, they can tell you where the city of gold really lies.

Over the centuries, explorers and scientists alike have tried to get at the truth of the city of gold. Did it ever exist? What does it mean for us today? Though many now doubt that El Dorado was a real place, history offers up some tantalizing clues that may actually reinforce the legend.

The real El Dorado wasn't a city at all

Chronicler Juan Rodríguez Freyle published the first reference to El Dorado in El Carnero, a chronicle of Spanish colonial exploits published in 1636. Freyle said that the legends stem from a native Muisca ritual where new rulers were coated in gold dust and then ceremonially bathed in Lake Guatavita.

According to Living With the Gods, Freyle's account was already familiar to many Europeans. The Muisca, also called the Chibcha, were a people who lived in the northern part of South America, in what's now Colombia. Prior to the 15th century, when the Muisca chose a new leader, they would first require that they seclude themselves in a cave. The ruler was to abstain from the company of women, salted food, and even daylight to cleanse himself.

Then, the new ruler emerged from the cave and went straight to Lake Guatavita. There, he would disrobe and attendants would cover his body with gold dust. They would then take a raft loaded with golden offerings out into the middle of the lake. As a crowd watched, the golden man would fling the offerings into the lake, cementing his place as the people's new leader.

The Spanish called the gold-covered ruler "El Dorado," sparking centuries of myth and speculation. Many began to wonder just where the Muisca got all their gold, suggesting that a people who would fling it into a lake must have more hidden elsewhere.

Gold meant something different to Indigenous people

The vast majority of European explorers in South America saw gold as the path to riches. For many Indigenous people of the continent, however, it held a very different role in their daily and spiritual lives.

Gold is a relatively soft metal, making it easy to shape. According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, for many people of the Americas, it held a clear connection to the sun, thanks to the metal's color and luster.

The Muisca people of present-day Colombia were especially skilled metalworkers, per Khan Academy. They tended to use the "lost wax" technique, where wax models are carved, covered in clay, and heated to melt the wax. Molten gold is then poured into the clay mold.

Muisca goldsmiths created an astonishing number of items for ritual offerings, called tunjos. These finely-detailed figurines were meant to be buried or submerged as a tribute to the gods. Over half of gold production was dedicated to tunjos and other offerings, the BBC reports. By studying the chemical signature of these objects, scientists have learned that they were offered up almost immediately after production.

The search for the city of gold led deep into the Andes

Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada was one of many conquistadors who went marching into the wilderness in search of hidden gold. He may have been one of the first Europeans to find El Dorado in the form of a golden ruler.

Quesada sailed from Spain to the coastal settlement of Santa Marta in 1535, says Britannica. Though he was supposed to act as the chief magistrate for the town, Quesada quickly caught the exploring bug. In 1536, he led a group of 900 men into what they called "New Granada." After months of marching, they made it to the region of modern-day Colombia inhabited by Muisca people. With people fleeing before the Spanish, Quesada counted it as a win and claimed the territory.

It's possible the Quesada or someone in his party heard of the legend of El Dorado, the gold-covered man said to lead the Muisca. Legends weren't enough for Quesada, The Conquest of New Granada reports. In 1569, he set out with a new expedition of 500 men in an attempt to conquer the Llanos, a grassland east of the Andes. Some speculate that he may have still been searching for a hidden horde of gold. Either way, the two-year expedition was a disaster. Quesada returned with only 25 men and, according to Invading Colombia, died in 1579.

Pizarro might have been dazzled by El Dorado

Over in what's now Peru, conquistador Francisco Pizarro might have been so dazzled by the specter of gold that he was willing to kill for it.

According to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, Pizarro was distantly related to Hernán Cortés, the conquistador who looted the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1521, gaining vast amounts of gold in the process. Meanwhile, other Spanish colonizers farther to the south were encountering chieftains decked out in similar splendor. Those same leaders, perhaps wanting the troublesome Spanish invaders to leave them alone, told tales of even greater hordes of gold farther into the mountains.

Pizarro took these stories all the way back to Spain, using them to persuade King Charles to finance an expedition into the Andes. Upon his return, he met with Atahualpa, the Inca ruler, and promptly kidnapped him. Atahualpa reportedly told Pizarro that, if he were spared, the king would give him a shockingly large amount of gold and silver. With riches soon coming in from other parts of the empire, he may have begun to wonder if there really was a source for all of this gold. According to Conquistadors, there were already tales of a mysterious, treasure-rich land of Peru. Taking the plunder, Pizarro had Atahualpa executed anyway in 1533.

Sir Walter Raleigh tried to get in on the gold

Spanish conquistadors were not the only European forces trekking into Native lands in search of gold and other riches. Sir Walter Raleigh, British explorer and occasional pirate, was certainly interested in the same legends. Plus, he was always up for a fight with the Spanish.

According to Live Science, Raleigh probably heard about El Dorado from Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa, who had been captured by Raleigh's men in 1586. Sarmiento provided just enough intel to give Raleigh a foothold in the New World and make more room for England.

Thanks to his new information, Raleigh focused on the Orinoco River in Venezuela, ThoughtCo says. He met with Topiawari, a Native chief who took a liking to Raleigh. Topiawari said there were definitely rich people far up in the mountains. Raleigh's subsequent expedition was miserable, with torrential rains and little evidence of gold.

Raleigh returned to England to little fanfare. Even worse, he was imprisoned in 1603 for plotting rebellion against the newly-crowned James I. The King would release Raleigh from the Tower of London in 1616 to try again for El Dorado, but with the express rule that Raleigh was to leave the Spanish alone. He didn't, History reports. This led not only to the death of his son Watt but to Raleigh's execution for treason in 1618.

People tried draining a lake to find El Dorado

According to chroniclers and legend, the Muisca people anointed their new rulers with gold dust and threw precious offerings into Lake Guatavita, north of modern-day Bogotá, Columbia. When word got back to the Europeans busy invading the continent, many became interested in this small lake at the bottom of a crater.

One of the boldest ventures took place courtesy of Antonio de Sepúlveda in the 1580s, Ancient History Encyclopedia claims. Sepúlveda hatched a scheme that required cutting out a piece of the crater itself in order to drain the lake. Presumably, all of the riches deposited there would be revealed.

It didn't quite work out that way. Sepúlveda did succeed in draining part of the lake and even found some golden offerings. Then, a landslide suddenly blocked the cut and allowed the lake to fill again. With rebellion brewing amongst the local people, Sepúlveda and his crew decided to leave.

Centuries later, in 1909, another team attempted a similar engineering project, South American Explorer reports. This time, Contractors Limited, a British company, dug a tunnel connecting to the lake. They drained the lake but quickly discovered that the mud of the lakebed was so soft that people sunk into the muck. Later, it hardened in the hot sun. They left for more equipment but, when they returned, mud in the drainage tunnel had also solidified and allowed Lake Guatavita to refill once again.

No one agreed on the location of the city of gold

Once the legend turned from a golden man into a golden city, most agreed that El Dorado was somewhere in South America. Or, maybe it was in Central America. Or, North America. Really, it began to seem as if no one agreed on anything more than a legendary location rich with gold.

Francisco Pizarro, the conquistador who had the last Inca king, Atahualpa, murdered, thought that it might be somewhere in the Andes, says ThoughtCo. In fact, his younger brother, Gonzalo Pizarro, led an expedition out of Quito, Peru in search of El Dorado. Gonzalo gave up and returned home. His lieutenant, Francisco de Orellana, forged ahead, found the Amazon and took it all the way back to the Atlantic coast. Orellana never came across the city of gold, however.

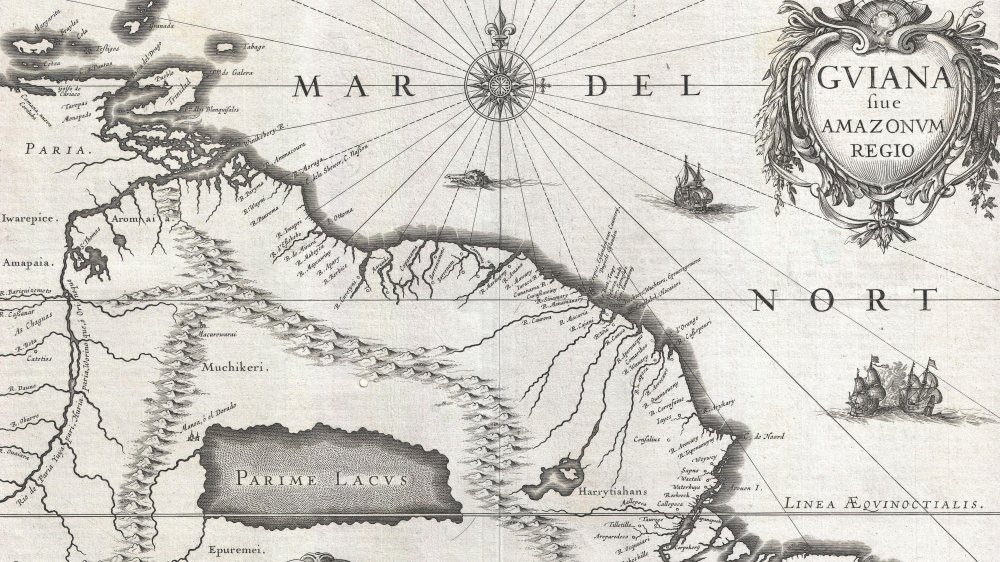

Others suspected that Guyana might hold the fabled Manoa, another commonly accepted name for the city of gold. As per ThoughtCo, Sir Walter Raleigh unsuccessfully tried to find Manoa and its lake, Parima, but to no avail.

The search for the city broke Lope de Aguirre

After a while, the territories held by Spain were lousy with conquistadors. Spanish men in metal armor traipsed through the countryside, claiming lands for their king, riches for themselves, and distributing woe to Native people. Some distinguished themselves through terrible acts, perhaps even driven mad by the lost city of gold.

Lope de Aguirre, "The Madman of El Dorado," was born a younger son of a noble but somewhat downtrodden family, according to ThoughtCo. As he wouldn't receive any inheritance, Aguirre went to the New World to seek his fortune. By the time he had crossed the Atlantic in the 1530s, he would have had plenty of dubious inspiration courtesy of Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro, who had ruined the Aztec and Incan empires respectively.

In 1560, Aguirre joined a new expedition to find El Dorado, per the British Library. The group found only disease, hostile natives, and little wealth of any sort. Aguirre mutinied and his expedition leader was murdered. Aguirre eventually declared the group to be the newly independent Kingdom of Peru.

Aguirre began to order the execution of those who seemed to threaten him, including the group's priest and anyone with noble blood (himself excluded, of course). They captured a Spanish settlement and Aguirre wrote a paranoid letter to King Philip II. Eventually, he was killed by loyal Spanish soldiers.

El Dorado wasn't the only mythical city in the region

As time went on, the legend of El Dorado became deeply muddled. The original story of a single man covered in gold and offering treasures to the gods, soon became the legend of a city full of riches. Then, as tales were passed along and perhaps embellished over a drink or two at the campfire, it got even more complicated. El Dorado went from being a singular city of gold to one of many.

While Spanish conquistadors and Sir Walter Raleigh were searching for El Dorado in northern South America, others took their efforts elsewhere. Some, like Francisco Vazquez de Coronado, even went as far as North America, National Geographic reports. Coronado was looking for the Seven Cities of Gold, a legend that one-ups the measly single city of El Dorado. Friar Marcos de Niza claimed to have seen one such city, Cibola, but it could be that he saw the monumental pueblos built by American Indian tribes.

Coronado set out in 1541, on what proved to be a disappointing journey. Never mind that he ended up in modern-day Kansas, according to History. They even found the legendary settlement of Quivira, says PBS, but it turned out to be a settlement bereft of gold, so no one got terribly excited. Coronado returned in shame and died in 1554 in Mexico City.

Two European scientists put the myth to rest

As the centuries moved on and the conquistadors, having little else to conquer, faded away, the legend of the city of gold persisted. Explorers still traveled into the wilds of South America and beyond, hoping that they might be the ones to stumble upon a hidden land full of riches. It took two 18th-century scientists to finally put the legend to rest.

It all began with Alexander von Humboldt, a Prussian explorer and polymath. By the late 1790s, Britannica says, Humboldt had determined that his true purpose in life was to learn everything he could about the planet. Unfortunately, the upheaval of the Napoleonic Wars had made his government unable to sponsor an expedition, so he went to Spain and got permission to visit the Spanish colonies of Central and South America.

In 1799, with botanist Aimé Bonpland, Humboldt sailed for the Americas, ThoughtCo reports. The pair spent the next five years in the colonies, covering thousands of miles of territory in the name of science. Along the way, they also went looking for El Dorado, partly because of the legends, partly out of scientific curiosity. As they relate in Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America, they found nothing to support the tales of a city of gold. Bonpland and Humboldt concluded that it was only a cool story and, for once, nearly everyone else seemed to agree.

Some parts of the El Dorado legend are real

Though 18th-century explorers like Aimé Bonpland and Alexander Humboldt made it clear that the idea of a city of gold almost certainly didn't exist, in some ways, El Dorado is still very real.

There's good evidence that the Muisca ritual of coating a newly-minted ruler in gold dust and then having him toss offerings into Lake Guatavita really happened. After all, per Atlas Obscura, Lake Guatavita is an actual landmark, just two hours outside of Bogotá, Colombia. Various attempts to drain the lake have uncovered artifacts, including bits of gold and jewels, though there's little evidence for a ridiculous treasure horde in the mud of the lakebed.

Others said that the lake full of riches was Lake Parima, says Terrae Incognitae. This lake was another proposed location for the mythical city of gold. Long thought to be a myth itself, recent geological surveys indicate that there may have been a lake in Brazil that would fit the description. A major earthquake likely drained the body of water starting in 1690, Proceedings of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences reports. By the 19th century, the lake would have been dry.

Even if there was a single, glorious, golden city, this region of South America proved to be rich in gold and other natural resources, A History of Mining in Latin America says. Many colonizers got rich from exploitative mining operations that still affect the environment today.

The city of gold just won't leave our imaginations

Even though most of civilization stopped believing in the existence of an actual city of gold, the legend of El Dorado is just too good for writers and filmmakers to resist.

For quite a few millennials, their introduction to the city of gold may have come from The Road to El Dorado, the 2000 animated film produced by Dreamworks before they began mining the rich vein of the Shrek franchise. Even though it was panned by critics, says Polygon, the film has achieved an unlikely afterlife. It may even be better than we remember, thanks largely to the charisma of lead voice actors Kenneth Branagh and Kevin Kline.

If you'd rather be depressed, there's always Werner Herzog's Aguirre, the Wrath of God. As per the MoMA blog, this 1972 film loosely follows the story of Lope de Aguirre, the conquistador who reportedly went mad on the search for El Dorado, tried to rebel against Spain, and paid for it with his life and the lives of many others. Herzog and star Klaus Kinski made a beautiful work that could also leave you contemplating the darkest side of humanity.

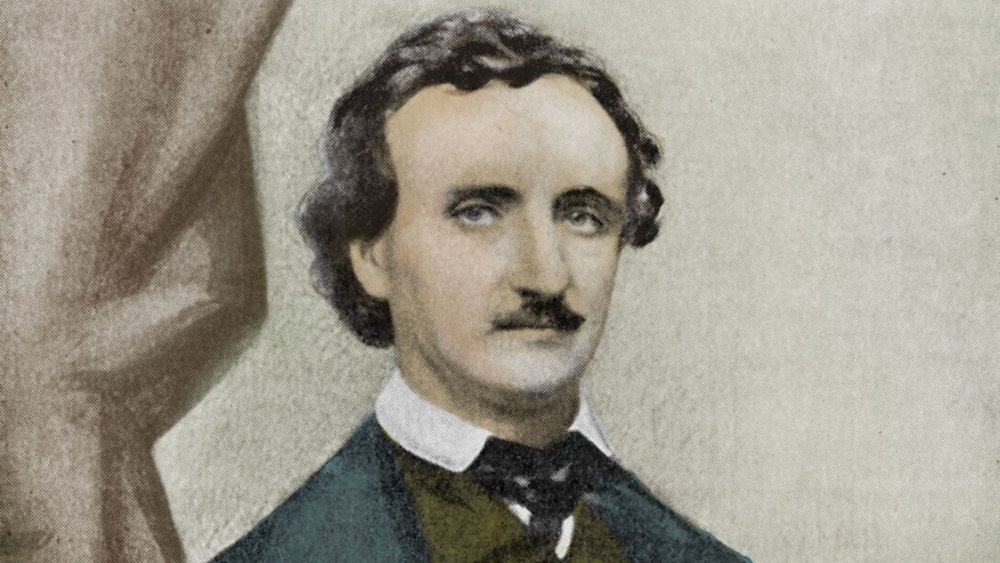

Even Edgar Allan Poe couldn't help himself when it came to a story as good as El Dorado's. His poem, "Eldorado," is more a meditation on futile quests and human mortality than a real city of gold.